Roger de La Fresnaye stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in the vibrant landscape of early 20th-century French art. Primarily associated with Cubism, he forged a unique path within the movement, distinguishing himself through a lyrical sensibility, a vibrant palette, and a consistent engagement with representational subjects, even while embracing geometric abstraction. His tragically short life, cut down by illness contracted during World War I, prevented a longer evolution, yet his pre-war work remains a testament to a sophisticated artistic vision that bridged tradition and the avant-garde. Born into privilege but dedicated to his craft, La Fresnaye navigated the complex currents of Parisian modernism, leaving behind a body of work that continues to resonate with its blend of intellectual structure and decorative appeal.

Aristocratic Roots and Academic Foundations

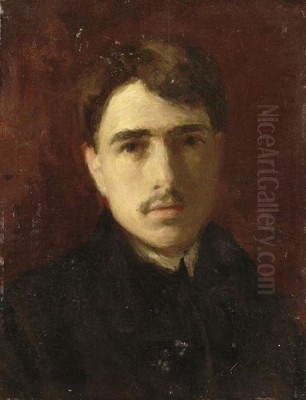

Roger-Noël-François de La Fresnaye was born on July 11, 1885, in Le Mans, Sarthe, France. He hailed from an aristocratic family with deep roots in Normandy; their ancestral home, the Château de La Fresnaye, was situated near Falaise. His father served as an officer in the French army, providing a background of tradition and structure that perhaps subtly informed the artist's later sense of composition. This privileged upbringing afforded him access to excellent education and the cultural milieu of Paris, which would become the crucible for his artistic development.

His formal artistic training began in Paris around 1903. He initially enrolled at the Académie Julian, a renowned private art school that attracted students from across the globe. This period, lasting until about 1904, provided him with foundational skills in drawing and painting. Following this, he sought a more rigorous, state-sanctioned education, entering the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in 1904. He remained there until 1908, immersing himself in the academic traditions that still held sway, even as modernist revolutions were brewing elsewhere in the city.

During his formative years at the Beaux-Arts and shortly thereafter, La Fresnaye also studied at the Académie Ranson. Here, he came under the direct influence of prominent artists associated with the Nabis movement, particularly Maurice Denis and Paul Sérusier. These mentors imparted lessons derived from Paul Gauguin and the Pont-Aven school, emphasizing simplified forms, flattened perspectives, subjective use of color, and a decorative, almost spiritual approach to painting. The impact of Denis and Sérusier is discernible in La Fresnaye's early works, which often feature Symbolist undertones, a certain elegance of line, and a thoughtful arrangement of color planes, laying the groundwork for his later stylistic explorations.

Embracing Cubism: The Puteaux Group and Section d'Or

By 1910, the artistic winds in Paris had shifted dramatically. The radical innovations of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque had given birth to Cubism, challenging centuries of representational tradition. While La Fresnaye absorbed the lessons of his Symbolist teachers, he was inevitably drawn to the intellectual rigor and formal experimentation of this new movement. However, he gravitated not towards the more austere, analytical Cubism of Picasso and Braque, but towards the circle of artists who gathered in the Parisian suburbs of Puteaux and Courbevoie.

This group, often referred to as the Puteaux Group, included figures like Jacques Villon and his brother Raymond Duchamp-Villon (in whose studio they often met), Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Fernand Léger, Francis Picabia, and František Kupka. These artists sought to develop a distinct form of Cubism, one that was often more colorful, dynamic, and sometimes infused with theoretical ideas drawn from mathematics and philosophy, such as the concept of the Golden Section (Section d'Or). They aimed to create an art that was modern and structured, yet perhaps more accessible and less hermetic than the work emerging from Montmartre.

La Fresnaye became an active participant in this milieu. He exhibited alongside these artists and contributed significantly to the development of what is sometimes termed "Salon Cubism," as they frequently showed their work at large public exhibitions like the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d'Automne. In 1912, this group organized a major exhibition under the banner "Section d'Or," held at the Galerie La Boétie. La Fresnaye was a prominent contributor, showcasing a substantial number of works that solidified his reputation as a leading figure among the alternative Cubists. His involvement demonstrated his commitment to the movement's core principles while signaling his intention to interpret them through his own refined lens.

A Unique Cubist Vision: Color, Form, and Decoration

What truly set Roger de La Fresnaye apart within the Cubist movement was his distinctive stylistic synthesis. While he adopted the geometric fragmentation and multiple viewpoints characteristic of Cubism, he never fully abandoned representational clarity or the importance of color and decorative harmony. Unlike the often monochromatic and intellectually challenging works of early Picasso and Braque, La Fresnaye's Cubism was typically vibrant, lyrical, and maintained a strong connection to the observable world.

His compositions often feature broad, simplified planes of color, arranged in dynamic, interlocking patterns. He retained a strong sense of underlying structure and drawing, perhaps a legacy of his academic training and Symbolist influences. Figures and objects, though abstracted and faceted, remain identifiable. There is a clarity and elegance to his work, a striving for balance and rhythm that feels distinct from the more aggressive deconstruction practiced by others. His approach could be described as a form of Synthetic Cubism, focusing on building up forms from geometric shapes, but infused with a personal sensitivity to color harmonies.

The influence of Robert Delaunay and Orphism is also evident, particularly in La Fresnaye's use of bright, contrasting colors to create dynamism and light. Delaunay's theories of "simultaneous contrasts" explored the optical effects of juxtaposing pure colors. La Fresnaye adapted these ideas, integrating vibrant hues like reds, blues, and yellows into his geometric frameworks. However, he generally remained more grounded in subject matter than the fully abstract compositions of Delaunay or Kupka, preferring to apply these chromatic principles to recognizable scenes and figures, lending them a modern energy while preserving their narrative or descriptive core. His work often possesses a distinct decorative quality, suggesting an integration of avant-garde principles with a more traditional French concern for aesthetic refinement.

Masterworks of the Pre-War Era

La Fresnaye's most celebrated works were produced in the fertile period between 1911 and the outbreak of war in 1914. These paintings exemplify his unique contribution to Cubism.

_Artillery_ (L'Artillerie), 1911: This dynamic composition reflects the growing interest in modern technology and perhaps the looming sense of conflict in pre-war Europe. It depicts soldiers maneuvering a field cannon, rendered in bold, simplified geometric forms and strong, primary colors. The figures are robust and monumental, their actions conveyed through energetic diagonal lines and fragmented planes. The work combines the structural language of Cubism with an almost Futurist sense of dynamism and a theme rooted in contemporary reality. It showcases La Fresnaye's ability to tackle modern subjects with a powerful, stylized visual language, blending abstraction with a clear narrative element.

_Married Life_ (La Vie Conjugale), 1912: In contrast to the martial theme of Artillery, this painting offers a more intimate glimpse into modern domesticity. It portrays a couple seated together within a simplified interior setting. The figures and their surroundings are broken down into geometric facets, yet they retain a sense of volume and presence. The color palette is softer, featuring harmonious blues, ochres, and grays, contributing to the tranquil, affectionate mood. Married Life demonstrates La Fresnaye's versatility, applying Cubist principles to a personal theme with sensitivity and decorative grace. It reflects the Section d'Or's interest in applying Cubism to a wider range of subjects beyond still lifes and portraits.

_The Conquest of the Air_ (La Conquête de l'air), 1913: Widely regarded as his masterpiece, this large canvas is a quintessential example of La Fresnaye's mature Cubist style. The painting depicts the artist himself alongside his brother, Henri, seated outdoors, with a hot air balloon floating prominently in the sky above a village landscape, possibly referencing their shared interest in aviation. The composition is a complex interplay of overlapping planes, vibrant colors (particularly the French tricolor blue, white, and red), and geometric shapes. It celebrates modernity, human ingenuity (the conquest of flight), and national pride. The figures are clearly discernible, yet fully integrated into the Cubist structure. Housed in the Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Conquest of the Air stands as a major statement of Salon Cubism, embodying its characteristic blend of abstraction, color, dynamism, and legible subject matter.

_Still Life with Inkwell_ (Nature morte à l'encrier), 1910: An earlier work, this still life shows La Fresnaye beginning to incorporate structural elements influenced perhaps by Paul Cézanne, a crucial precursor to Cubism. While less fragmented than his later works, it demonstrates his sensitivity to form, composition, and the arrangement of objects in space, hinting at the geometric explorations to come. It reveals his thoughtful approach to composition and his burgeoning interest in analyzing form.

These works, among others from this period, established La Fresnaye as a significant innovator, capable of synthesizing diverse influences – from Symbolism and Cézanne to the latest developments in Cubism and Orphism – into a coherent and personal artistic language.

The Profound Impact of War

The outbreak of World War I in August 1914 brought a sudden and brutal halt to the vibrant artistic experimentation in Paris. Like many of his contemporaries, including artists such as Georges Braque, Fernand Léger, and Albert Gleizes, Roger de La Fresnaye was mobilized into the French army. He served in the infantry, experiencing the harsh realities of trench warfare firsthand. This period marked a dramatic rupture in his life and artistic career.

His military service had devastating consequences for his health. He contracted pulmonary tuberculosis, a widespread and often fatal disease at the time, exacerbated by the grueling conditions at the front. The illness forced his discharge from the army in 1918. Though the war had ended, its impact on La Fresnaye was permanent. His health remained fragile, progressively deteriorating over the following years.

The war also precipitated a significant shift in his artistic direction, mirroring a broader trend in European art known as the "return to order" (rappel à l'ordre). Many avant-garde artists, disillusioned by the war's destruction and seeking stability, moved away from radical abstraction towards more classical, representational styles. La Fresnaye's post-war work reflects this change. He largely abandoned the complex geometric fragmentation and vibrant palette of his Cubist period. His focus shifted towards drawing, linearity, and more traditional modes of representation, often imbued with a sense of quiet melancholy or introspection.

Later Years, Stylistic Evolution, and Personal Life

Seeking warmer climates beneficial to his health, La Fresnaye spent his final years primarily in the south of France, particularly in Grasse, known for its favorable environment for those suffering from respiratory ailments. Despite his declining physical condition, he continued to work, though his output inevitably slowed. His artistic focus narrowed, concentrating mainly on figurative subjects, including portraits, nudes, and landscapes, as well as meticulously rendered drawings.

His post-war style is characterized by a greater emphasis on realism and classical clarity. The influence of masters like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, known for his precise linearity and smooth finish, can sometimes be detected in the refined contours and sculptural quality of La Fresnaye's later drawings and paintings. Works from this period, such as The Cattle Drover (Le Bouvier), depict subjects like peasants with a solidity and realism far removed from his pre-war Cubist abstractions. While these later works may lack the revolutionary fervor of his Cubist phase, they possess a distinct poignancy and demonstrate his enduring commitment to draftsmanship and formal control, even as his health failed.

Insights into his personal life and thoughts during this period, as well as earlier, can be gleaned from his correspondence. Letters reveal aspects of his personality, his reflections on art and life, his friendships, and his views on fellow artists. Notably, his letters sometimes mention a complex relationship with his cousin, Marie Valentine, adding a layer of personal drama to his biography. These documents provide valuable context for understanding the man behind the art during his most productive years and his final, challenging phase. Roger de La Fresnaye died from tuberculosis in Grasse on November 27, 1925, at the tragically young age of 40.

Relationships and Artistic Context

Roger de La Fresnaye's career unfolded within a rich network of artistic relationships, marked by influence, collaboration, and differentiation. His journey reflects the dynamic interactions that characterized the Parisian art world.

Early Influences: His initial training exposed him to the academic tradition, but the most significant early impact came from the Nabis painters Maurice Denis and Paul Sérusier, who instilled in him a sense of decorative composition and subjective color use. Like nearly all aspiring modernists of his generation, he also absorbed the lessons of Paul Cézanne, whose structural analysis of form was fundamental to the development of Cubism.

Cubist Circle (Puteaux/Section d'Or): His closest artistic allies were found within the Puteaux Group and the Section d'Or. He shared ideas and exhibited alongside Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger (authors of the first major treatise on Cubism, Du "Cubisme"), the brothers Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Fernand Léger (whose interest in modern, mechanical forms sometimes paralleled La Fresnaye's), Francis Picabia, and the Spanish painter Juan Gris, who also developed a highly colored and structured form of Synthetic Cubism. This group fostered a collective identity distinct from the Picasso-Braque axis.

Dialogue with Picasso and Braque: While deeply engaged with Cubism, La Fresnaye consciously diverged from the path forged by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. He admired their innovations but chose not to adopt the austerity of their Analytical Cubism or the collage techniques they pioneered. His work remained more visually accessible, colorful, and tied to traditional genres, representing a different, perhaps more moderate, interpretation of Cubist principles.

Orphism Connection: His use of color shows a clear dialogue with Robert Delaunay, the leading figure of Orphism (or Orphic Cubism). La Fresnaye embraced Delaunay's emphasis on vibrant, simultaneous color contrasts to create rhythm and light, as seen in The Conquest of the Air. However, he integrated these chromatic ideas into compositions that retained more defined subjects and structures compared to Delaunay's increasingly abstract "Windows" and "Circular Forms." Sonia Delaunay was also part of this interconnected circle exploring color and abstraction.

Other Contemporaries: He would have been aware of other figures navigating Cubism, such as André Lhote, who, like La Fresnaye, sought to reconcile Cubist structure with figurative representation and traditional composition. The broader context included Fauvist artists like Henri Matisse, whose bold use of color prefigured some aspects of Orphism, and precursors like Gauguin, whose influence resonated through the Nabis.

La Fresnaye's position was thus one of active engagement: absorbing influences, participating in group movements, and ultimately carving out a distinct artistic identity characterized by synthesis and refinement rather than radical rupture.

Legacy and Conclusion

Despite a career tragically curtailed by illness and war, Roger de La Fresnaye left an indelible mark on French modernism. His primary contribution lies in his development of a unique and appealing variant of Cubism, one that successfully integrated the movement's revolutionary formal language with a traditional French appreciation for color, harmony, and decorative elegance. He demonstrated that the geometric structures of Cubism could be applied to a wide range of subjects, from modern life and technology to intimate domestic scenes, without sacrificing legibility or aesthetic pleasure.

His work stands as a key example of the Puteaux Group and Section d'Or's collective effort to broaden Cubism's appeal and theoretical base. Paintings like The Conquest of the Air remain iconic representations of this phase of the movement, capturing the optimism and dynamism of the pre-war era through a sophisticated blend of abstract form and vibrant color. While perhaps not as fundamentally transformative as the contributions of Picasso or Braque, La Fresnaye's art offered a compelling alternative, proving the adaptability and richness of the Cubist idiom.

His post-war shift towards a more classical, linear style, while reflecting a broader European trend, also underscores his versatility and enduring commitment to draftsmanship. Though his later works are less well-known, they reveal a continued artistic sensibility grappling with form and representation under difficult personal circumstances.

Roger de La Fresnaye's legacy resides in the quality and distinctiveness of his work. He remains an important figure for understanding the diversity within Cubism and the complex interplay between avant-garde experimentation and artistic tradition in the early 20th century. His paintings continue to be admired for their intellectual rigor, visual appeal, and the unique lyrical voice they brought to the often-austere world of early modern abstraction. He was a painter of synthesis, skillfully bridging the gap between the old and the new, leaving behind a body of work that testifies to a refined and thoughtful artistic vision.