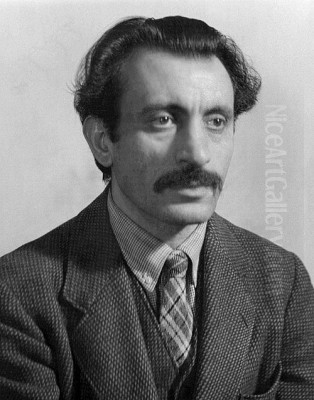

Arshile Gorky stands as a seminal figure in twentieth-century American art, a vital conduit between European modernism, particularly Surrealism, and the burgeoning Abstract Expressionist movement in New York. His life, marked by profound personal tragedy originating in the Armenian Genocide, deeply informed his art, resulting in a body of work characterized by lyrical abstraction, biomorphic forms, and intense emotional resonance. Born Vosdanik Manoog Adoian, his journey from the shores of Lake Van to the forefront of the American avant-garde is a story of resilience, reinvention, and relentless artistic exploration. Gorky's unique synthesis of memory, observation, and painterly innovation carved a distinct path that profoundly influenced the generation of artists who would define postwar American painting.

Early Life and the Shadow of Armenia

Vosdanik Manoog Adoian was born on April 15, 1904, in the village of Khorkom, situated on the shores of Lake Van in the Van Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire, historically part of Western Armenia (now in modern-day Turkey). His early childhood was steeped in the rich cultural traditions of Armenia but overshadowed by the looming political turmoil and persecution of Armenians within the Ottoman Empire. The idyllic landscape of his youth, filled with orchards, gardens, and ancient stone carvings, would later resurface as potent motifs in his mature abstract works.

The defining trauma of Gorky's early life was the Armenian Genocide, which began in 1915. Fleeing the massacres, the Adoian family endured horrific conditions, including forced marches and starvation. This period culminated in the tragic death of his mother, Shushan, from starvation in Yerevan in 1919, an event that would haunt Gorky for the rest of his life and become a central theme in his art. The image of his mother, particularly from a photograph taken around 1912 showing a young Gorky standing beside her, became an enduring symbol of loss and memory.

In 1920, Gorky and his younger sister Vartoosh managed to emigrate to the United States, joining their father who had previously settled in Providence, Rhode Island. Seeking to distance himself from his traumatic past and perhaps create a more "exotic" artistic persona, Vosdanik Adoian reinvented himself. He adopted the name Arshile Gorky, claiming relation to the Russian writer Maxim Gorky (which was untrue) and often fabricating details about his background, sometimes suggesting Georgian or Russian origins. This act of self-creation was part of his complex negotiation of identity as an immigrant artist navigating the American art world.

Forging an Identity in America

Upon arriving in America, Gorky initially lived with relatives in Watertown, Massachusetts, and briefly worked in a rubber factory. His artistic inclinations soon led him to Boston, where he enrolled in the New School of Design on Huntington Avenue. Even in these early years, his talent and intense dedication were apparent. He absorbed lessons quickly but was largely self-directed, spending countless hours studying masterworks in museums, particularly the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

In 1924, Gorky moved to New York City, which was rapidly becoming the center of American artistic innovation. He continued his self-education, immersing himself in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He studied the techniques of Old Masters like Paolo Uccello and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, alongside modern pioneers. His early works from this period clearly show his process of assimilation, demonstrating a remarkable ability to mimic the styles of artists he admired.

Gorky soon secured a teaching position at the Grand Central School of Art, located within Grand Central Terminal. He taught there from 1925 until 1931, becoming a charismatic, if sometimes dogmatic, instructor. His teaching emphasized rigorous draftsmanship and a deep understanding of art history. Among his students were artists who would later recall his passionate advocacy for modern art, particularly the work of Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso. His role as an educator provided him with a modest income and placed him within the active artistic community of New York.

Embracing European Modernism

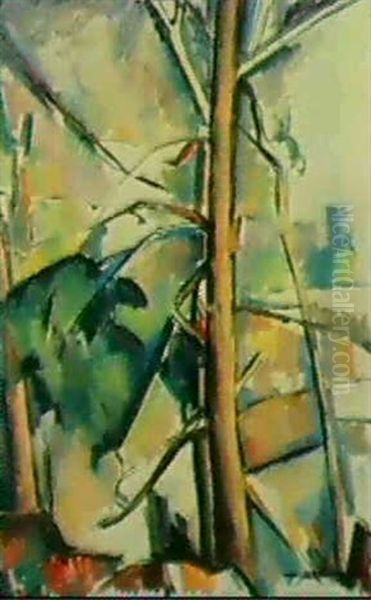

Throughout the late 1920s and 1930s, Gorky embarked on an intensive "apprenticeship" to European modern masters. He believed that understanding the foundations laid by these artists was essential before developing a truly personal style. Paul Cézanne was an early and crucial influence; Gorky adopted his structured compositions, visible brushwork, and approach to landscape and still life, producing numerous works directly inspired by the French Post-Impressionist.

The influence of Pablo Picasso became paramount in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Gorky meticulously studied Picasso's Synthetic Cubist phase, absorbing its flattened perspectives, fragmented forms, and intellectual rigor. Works from this period often resemble Picasso's so closely that they have been described as acts of profound identification rather than mere imitation. Gorky saw this process not as copying, but as a way to internalize the language of modernism, mastering its grammar before composing his own sentences.

Other significant influences during this formative period included Georges Braque, Fernand Léger, and Joan Miró. From Léger, Gorky learned about bold outlines and mechanistic forms, while Miró's biomorphic shapes and playful surrealism began to seep into his compositions, hinting at the direction his art would later take. He also looked towards the abstract compositions of Wassily Kandinsky, particularly his early, lyrically expressive works. Gorky synthesized these diverse influences, gradually moving away from direct emulation towards a more personal integration of modernist principles.

The Artist and His Mother: A Pivotal Work

Among the most significant works of Gorky's career are the two primary versions of The Artist and His Mother, painted between approximately 1926 and 1936 (though he may have continued working on them later). Based directly on the 1912 photograph taken in Van, these paintings are haunting meditations on memory, loss, and his Armenian heritage. The process of creating these works was long and arduous, reflecting the deep emotional weight they carried for the artist.

The paintings depict a young, formally dressed Gorky standing stiffly beside his seated mother, Shushan. Her large, almond-shaped eyes stare directly out, conveying a profound sadness and resilience. Gorky rendered the figures with a deliberate flatness, echoing Armenian manuscript illumination and folk art, combined with the formal simplifications learned from Ingres and Picasso. The surfaces are meticulously worked, with layers of paint scraped down and reapplied, giving them a dense, almost sculptural quality.

These portraits are more than just representations; they are icons of remembrance. Gorky transforms the photographic source into a timeless image of maternal love and devastating loss. The figures seem detached yet intimately connected, frozen in a moment before the impending catastrophe. The paintings serve as a testament to his mother's enduring presence in his psyche and stand as powerful examples of how Gorky infused modernist formalism with deeply personal and culturally specific content. They mark a crucial point where his technical mastery began to serve profound emotional expression.

Encountering Surrealism

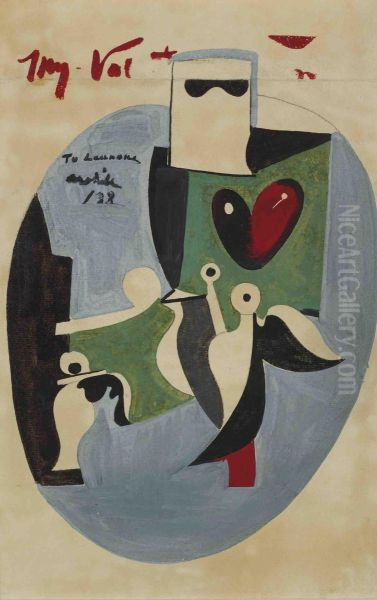

The arrival of numerous European Surrealist artists in New York during World War II, fleeing the conflict in Europe, had a profound impact on Gorky. Artists like André Breton, Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, and Roberto Matta brought Surrealist ideas directly into the New York art scene. Gorky, already familiar with Surrealism through publications and exhibitions, found himself in direct contact with its leading proponents. He formed a particularly close, though later fraught, relationship with the younger Chilean Surrealist, Matta.

Gorky was especially drawn to the Surrealist concept of psychic automatism – accessing the unconscious mind to create art free from rational control. However, he adapted this technique, blending spontaneous drawing and painting with careful observation of nature and deliberate compositional structuring. He did not fully embrace the purely automatic methods of some Surrealists but used their ideas as a catalyst to unlock his own subconscious imagery, often rooted in memories of Armenia and observations of the natural world.

André Breton, the founder and chief theorist of Surrealism, recognized Gorky's unique talent. In 1945, Breton wrote the preface for Gorky's first major solo exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery, famously declaring Gorky's art a "hybrid" and praising his ability to capture the "rhythm of nature." Breton saw Gorky as an authentic link between Surrealism and the natural world, someone who could tap into universal symbols through personal experience. This endorsement solidified Gorky's position within the avant-garde, even as his style was already evolving beyond orthodox Surrealism.

The Emergence of a Unique Vision

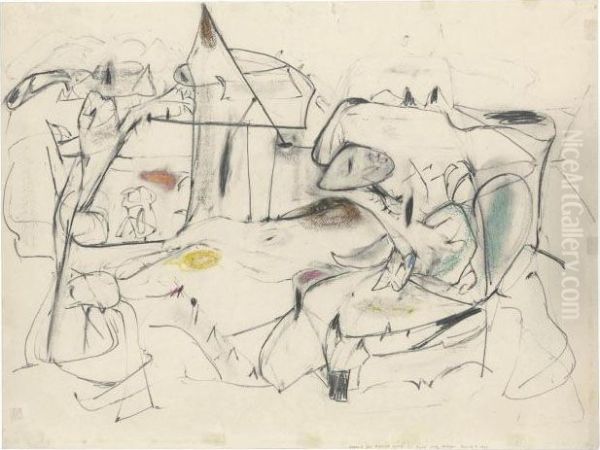

By the early 1940s, Gorky's art underwent a dramatic transformation, moving decisively towards the distinctive abstract style for which he is best known. This breakthrough was partly fueled by summers spent sketching outdoors, first in Connecticut in 1942 and later at Crooked Run Farm, his wife's parents' home in Virginia, from 1943 onwards. Direct contact with nature – observing plants, insects, and landscapes – provided him with a rich vocabulary of organic forms.

His technique shifted towards thinner washes of paint, often diluted with turpentine, creating veils of luminous color. Line became fluid and calligraphic, detached from purely descriptive purposes, instead carving out ambiguous, biomorphic shapes that float and interact within shallow, atmospheric spaces. These forms often suggest anatomical parts, botanical elements, or microscopic organisms, yet they remain elusive and evocative rather than specific. Titles like Garden in Sochi (a series referencing childhood memories of his father's garden) exemplify this fusion of memory, nature, and abstraction.

Gorky's mature style synthesized the lessons of Cubism (structural organization), Surrealism (automatism, biomorphism, psychological depth), and his own deep connection to memory and nature. He created a unique pictorial language where line and color operate semi-independently, generating energy and emotion. This period saw the creation of many of his most celebrated works, establishing him as a crucial precursor to Abstract Expressionism, influencing artists who were moving towards large-scale, gestural abstraction.

Masterworks of the 1940s

The period from 1943 to 1947 marked the apex of Gorky's artistic production, yielding a series of masterpieces that cemented his reputation. Water of the Flowery Mill (1944) exemplifies his mature style, with its delicate, flowing lines and washes of vibrant color suggesting natural forms – perhaps water, plants, and insects – dissolved into a lyrical abstraction. The painting evokes the sensation of being immersed in nature, blending observation with dreamlike imagery.

Perhaps his most famous work from this period is The Liver Is the Cock's Comb (1944). This large, complex canvas pulsates with energy, filled with dynamic, interlocking biomorphic shapes rendered in brilliant, sometimes clashing colors. The title itself is enigmatic, typical of Gorky's poetic and often obscure references. Art historians have interpreted the imagery in various ways, suggesting references to fertility, Armenian folklore, anatomical diagrams, or simply the vibrant chaos of life itself. It is widely considered a landmark of American painting, bridging Surrealist automatism with the scale and energy of emerging Abstract Expressionism.

Other crucial works include How My Mother's Embroidered Apron Unfolds in My Life (1944), which connects his abstract vocabulary back to specific, cherished memories, and The Betrothal (I and II, 1947), paintings filled with both eroticism and a sense of underlying tension. Agony (1947), painted after a devastating studio fire and a cancer diagnosis, reflects his increasing personal turmoil, with darker colors and more jagged, aggressive forms disrupting the earlier lyricism. These works demonstrate Gorky's extraordinary ability to translate complex emotional states and deeply buried memories into powerful visual form.

Gorky and His Contemporaries

Gorky occupied a unique position in the New York art world, respected by both the exiled European Surrealists and the younger generation of American painters. His closest artistic friendship was arguably with Willem de Kooning. They met in the 1930s and shared a deep mutual admiration and artistic dialogue. De Kooning later acknowledged Gorky's profound influence, stating, "I met a lot of artists — but then I met Gorky... He knew everything." Their relationship was one of shared struggle, intense discussion about art, and mutual support.

Gorky also maintained connections with artists like Stuart Davis and John Graham, who were important figures in introducing European modernism to American artists in the 1920s and 30s. Graham, in particular, included Gorky in his influential 1942 exhibition, "French and American Painting," alongside Picasso, Braque, and emerging Americans like de Kooning and Jackson Pollock. This helped position Gorky within the lineage of modern art.

He interacted with the Surrealist group centered around André Breton, including Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, and Roberto Matta. While respected by them, Gorky maintained a degree of independence. His relationship with Matta was initially collaborative but later soured dramatically due to personal issues. Gorky also knew the sculptor David Smith, sharing an interest in abstracted forms, and had contact with Isamu Noguchi. Although Gorky died before Abstract Expressionism fully coalesced as a movement, his pioneering work was crucial for artists like Pollock, de Kooning, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman, who recognized him as a vital forerunner who had successfully synthesized European traditions with a new, distinctly American sensibility.

A Life Marked by Tragedy

Despite his artistic triumphs in the mid-1940s, Gorky's personal life became increasingly fraught with misfortune, leading to a devastating spiral in his final years. In January 1946, a fire destroyed his Connecticut studio, consuming approximately twenty-seven paintings and numerous drawings – a significant loss of recent work that deeply affected him.

Shortly after the fire, Gorky was diagnosed with rectal cancer and underwent a painful colostomy operation. The physical and psychological toll of the surgery was immense, leaving him weakened and often depressed. His relationship with his wife, Agnes Magruder (nicknamed "Mougouch"), also began to deteriorate during this period.

In June 1948, Gorky was involved in a serious car accident while riding as a passenger with his dealer, Julien Levy. He suffered a broken neck and other injuries, and crucially, his painting arm was temporarily paralyzed. This injury, combined with his ongoing health problems and depression, plunged him into despair, fearing he might never be able to paint again with the same facility. The final blow came when his wife, Agnes, left him, allegedly due to his increasingly difficult temperament and her affair with Roberto Matta.

The Final Act and Suicide

Overwhelmed by the cumulative weight of physical pain, emotional loss, artistic setbacks, and the paralysis of his painting arm, Arshile Gorky fell into a deep depression in the summer of 1948. Friends observed his profound despair and erratic behavior. He felt abandoned and believed his creative life was over.

On July 21, 1948, at the age of 44, Arshile Gorky ended his life. He hanged himself in a barn on a property in Sherman, Connecticut. Nearby, he had scrawled a message in chalk: "Goodbye My Loveds." His suicide sent shockwaves through the New York art world, marking the tragic end of a life that had endured immense hardship yet produced art of extraordinary beauty and innovation.

Gorky's death has often been romanticized as the ultimate act of a tortured artist, but it was the culmination of specific, devastating personal circumstances superimposed on a life already deeply marked by trauma. His suicide underscored the intense pressures and emotional vulnerability experienced by many artists of his generation who were pushing the boundaries of modern art.

Legacy and Influence

Arshile Gorky's legacy is that of a pivotal figure in modern art, an artist who forged a crucial link between European Surrealism and American Abstract Expressionism. His profound understanding and assimilation of modernist masters like Cézanne, Picasso, and Miró, combined with his adaptation of Surrealist automatism, allowed him to create a unique and highly personal abstract language. He demonstrated how abstraction could be deeply rooted in personal experience, memory, and the natural world.

His influence on the first generation of Abstract Expressionists was significant, particularly on Willem de Kooning, who considered Gorky a mentor figure. Gorky's use of fluid line, ambiguous biomorphic forms, thin paint application, and emotionally charged compositions provided a model for artists seeking to move beyond established European styles. He showed that American art could be both sophisticated in its dialogue with European modernism and intensely personal and original.

Today, Gorky is recognized as one of the most important American painters of the 20th century. His works are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Tate Modern in London, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Retrospectives of his work continue to affirm his status as a brilliant innovator whose art, born from tragedy and resilience, speaks with enduring power about the complexities of memory, nature, and the human condition. He remains a testament to the transformative power of art in the face of profound adversity.