Joaquín Torres-García stands as a monumental figure in the landscape of twentieth-century modern art. A painter, sculptor, theorist, teacher, and writer, his life and work bridged continents and artistic movements, forging a unique path that synthesized European avant-garde principles with the rich cultural heritage of the Americas. Born in Montevideo, Uruguay, in 1874, and passing away there in 1949, Torres-García's journey took him from the vibrant artistic circles of Barcelona and Paris to the bustling metropolis of New York, before culminating in a transformative return to his homeland, where he established a lasting legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Catalonia

Though born in Uruguay, Torres-García's formative artistic years were spent in Catalonia, Spain. His family relocated to Mataró, near Barcelona, when he was a teenager. He immersed himself in the region's dynamic cultural scene, studying at the School of Fine Arts (La Llotja) and the Baixas Academy in Barcelona. This period coincided with the flourishing of Catalan Modernisme and its successor movement, Noucentisme, both of which left an imprint on his early development.

During his time in Barcelona, he became associated with the Cercle Artístic de Sant Lluc, a society that promoted a moral and artistic seriousness. A significant early collaboration involved working with the iconic architect Antoni Gaudí. Torres-García was commissioned to create stained-glass windows for the Palma Cathedral in Mallorca, which Gaudí was renovating. He also reportedly worked on designs for Gaudí's masterpiece, the Sagrada Família in Barcelona, though Gaudí himself apparently did not view Torres-García primarily as a fellow artist in the same vein. This early exposure to architectural structure and decorative arts would resonate throughout his later work.

His early paintings from this period often reflected the classical serenity and ordered composition associated with Noucentisme, depicting idyllic scenes and figures with a certain Mediterranean clarity. However, even then, hints of his later interest in structure and symbolic representation were beginning to emerge.

Journeys Abroad: New York and the Parisian Avant-Garde

Seeking broader horizons, Torres-García moved to New York City in 1920. The dynamism and verticality of the American metropolis captivated him. He exhibited his work at venues like the Whitney Studio Club (a precursor to the Whitney Museum) and with the Society of Independent Artists. During this time, he connected with figures in the American modernist scene, including Stuart Davis, Max Ernst (though primarily associated with Europe, Ernst spent time in the US), Charles Demuth, and potentially Joseph Stella. His work absorbed the energy of the city, reflected in paintings depicting street scenes, advertisements, and the architectural grid of Manhattan.

Financial struggles and perhaps a sense of artistic isolation prompted a move to Paris in 1926, placing him at the heart of the European avant-garde. This period was crucial for his artistic evolution. He interacted with leading figures like Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, and Julio González. He also became acquainted with Constantin Brâncuși, whose approach to essential forms likely resonated with him.

In Paris, Torres-García became deeply engaged with abstract art movements. He co-founded the influential group "Cercle et Carré" (Circle and Square) in 1930 alongside Belgian artist and writer Michel Seuphor. This group brought together artists committed to geometric abstraction and constructivist principles, including figures like Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg (founders of De Stijl), Jean Arp, Wassily Kandinsky, and Le Corbusier. Cercle et Carré organized a landmark exhibition and published a journal, advocating for an art based on structure, order, and universal principles, in contrast to the burgeoning Surrealist movement, which Torres-García actively opposed through debates and writings. His painting Estructura (Structure) from 1934 exemplifies the geometric clarity and intellectual rigor he pursued during this time.

The Theory of Constructive Universalism

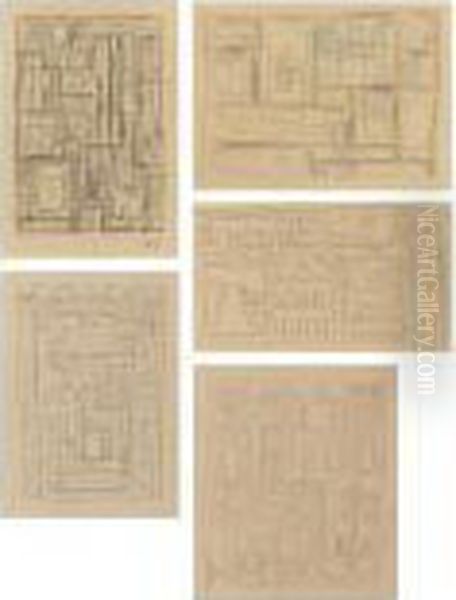

It was during his European years, particularly in Paris, that Torres-García fully developed his seminal theory: Constructive Universalism (Universalismo Constructivo). This complex artistic philosophy sought a synthesis between the geometric abstraction of European modernism (particularly Cubism and Neoplasticism) and the symbolic, often geometric, art of ancient and indigenous cultures, especially those of the Americas (like Inca, Maya, and Nazca).

Constructive Universalism was built upon the idea of a fundamental, universal order underlying reality, which could be expressed through art. Key elements included:

1. The Grid: A structural framework, often orthogonal, providing order and rhythm to the composition. This grid was not merely a formal device but represented a cosmic or intellectual structure.

2. Pictograms and Symbols: Within the grid, Torres-García placed schematic, symbolic images representing universal concepts or elements of everyday life: the sun, the moon, stars, fish, boats, clocks, keys, numbers, letters, human figures, tools, hearts, and architectural elements. These symbols were meant to be intuitively understood, bridging the gap between abstraction and figuration.

3. Integration of Opposites: The theory aimed to harmonize reason and intuition, the abstract and the concrete, the universal and the particular, the ancient and the modern.

4. Ethical Dimension: Art was seen as having a constructive role in society, reflecting and contributing to a sense of order and shared human experience.

He articulated these ideas extensively in writings such as "Notes about Art" (Notes sobre Art) and later manifestos. Constructive Universalism became the guiding principle for the rest of his artistic career.

Return to Montevideo and the Taller Torres-García

In 1934, after decades abroad, Torres-García made the pivotal decision to return to his native Uruguay. This move was driven by a desire to establish an art movement rooted in American soil, reversing the traditional flow of influence from Europe to Latin America. He famously declared, "Our North is the South," advocating for Latin American artists to find inspiration in their own continent's heritage while engaging with universal artistic principles.

Upon his return, he founded the Asociación de Arte Constructivo (Association of Constructive Art) and, most significantly, the Taller Torres-García (Torres-García Workshop) in 1943. The Taller was more than just an art school; it was a collective workshop based on Renaissance and medieval guild models, promoting collaboration, the integration of arts and crafts, and the principles of Constructive Universalism.

The Taller became a powerhouse of artistic activity and education, profoundly shaping modern art not only in Uruguay but across Latin America. Torres-García guided his students in painting, sculpture, ceramics, tapestry, and mural painting, emphasizing craftsmanship and the application of Constructive Universalist principles. The Taller fostered a sense of community and shared purpose, producing a distinctive collective style while allowing for individual expression within the shared framework.

Prominent artists who emerged from the Taller include Julio Alpuy, Gonzalo Fonseca, José Gurvich, Augusto Torres (his son), Horacio Torres (another son), Manuel Pailós, Francisco Matto, and many others. These artists carried the Taller's influence forward, adapting and evolving its principles in their own diverse careers, contributing significantly to the development of abstract and constructive art in the region.

Key Works and Evolving Artistic Style

Torres-García's mature style is characterized by the application of Constructive Universalism. His paintings typically feature a prominent grid structure, often rendered in thick black lines. The compartments created by the grid are filled with his characteristic pictograms and symbols, painted in a deliberately restrained palette often dominated by primary colors (red, yellow, blue) along with black, white, and earth tones. The texture is often rough, emphasizing the materiality of the paint and surface.

His works evoke a sense of timelessness, connecting ancient symbols with modern life. Titles often reflect this synthesis, such as Constructive City with Universal Man (a recurring theme). Works like Cosmic Monument (1938), a public sculpture in Montevideo's Parque Rodó made of pink granite blocks carved with symbols, translate his pictorial language into three dimensions, embodying ideas of permanence and universal order through geometric forms like cubes, spheres, and pyramids.

His reflections on his time in America continued to surface, as seen in works sometimes titled Bird’s Eye View of New York or similar, where the city's structure is rendered through his symbolic grid system, likely painted after his return, synthesizing memory and theory. The exact dating of some New York-themed works remains a subject of discussion among scholars.

Beyond painting and sculpture, Torres-García applied his aesthetic to various media. His early work included significant mural projects in Barcelona, such as those for the Palau de la Generalitat. He also designed stage sets and costumes. Notably, influenced perhaps by his interest in education and the ideas of educators like Maria Montessori, he designed and manufactured wooden toys under the name Aladin Toys during his time in New York and later. These assemblable, often unpainted toys embodied his constructive principles, encouraging creativity and spatial understanding in children.

Exhibition History and Recognition

Joaquín Torres-García's work was exhibited regularly throughout his career, both in solo shows and important group exhibitions across Europe, the United States, and Latin America. His participation in the Cercle et Carré exhibition in Paris (1930) and shows at the Whitney Studio Club and Gallatin's Gallery of Living Art were crucial in establishing his international presence.

After his return to Uruguay, his exhibition activity centered more on Montevideo, where he frequently showed his work and that of the Taller. Posthumously, his reputation continued to grow internationally. Significant retrospectives were held in Paris (1955) and Amsterdam (Stedelijk Museum, 1961), which were instrumental in solidifying his place in the history of abstract art.

More recently, major exhibitions have brought renewed attention to his work. The landmark retrospective "Joaquín Torres-García: The Arcadian Modern" at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in 2015-2016, featuring nearly 190 works, was the first large-scale US survey of his oeuvre. Exhibitions celebrating his 150th anniversary were held in 2023-2024 in locations like Barcelona.

His works are held in major museum collections worldwide, including MoMA, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (New York), the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (Madrid), the Musée National d'Art Moderne (Centre Pompidou, Paris), the Tate Modern (London), the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA), and the Museo Torres García in Montevideo, which is dedicated to preserving and promoting his legacy and that of the Taller.

Controversies and Anecdotes

Like many influential artists, Torres-García's career was not without its complexities and controversies. His strong theoretical positions, particularly his opposition to Surrealism, placed him firmly within the ideological debates of the Parisian art world.

His observations during World War II regarding the paradox of art's perceived value being questioned while its market price soared highlight his critical engagement with the social and economic dimensions of the art world.

In more recent times, his name surfaced in connection with art market controversies. Reports emerged, particularly from Brazil, alleging that certain works attributed to him were involved in money laundering schemes, underscoring the unfortunate reality of how culturally significant artworks can become entangled in illicit activities. This reflects broader issues within the international art market rather than a direct controversy involving the artist during his lifetime.

On a personal level, sources suggest he faced emotional and familial challenges, particularly in his later years, including conflicts and the impact of loss. While biographical details can offer context, his artistic output remained remarkably consistent and focused on his core principles until his death.

Influence and Lasting Legacy

Joaquín Torres-García's influence on modern and contemporary art is profound and multifaceted. He is widely regarded as one of the most important artists to emerge from Latin America in the 20th century. His greatest legacy lies in the development of Constructive Universalism, a unique artistic language that offered a powerful alternative to mainstream European modernism by integrating non-Western, indigenous traditions.

His concept of "The School of the South" fundamentally shifted perspectives for many Latin American artists, encouraging them to value and explore their own cultural roots as a source of universal artistic expression. The Taller Torres-García remains a landmark pedagogical experiment, demonstrating the power of collective artistic practice and mentorship. Its impact extended for decades, influencing subsequent generations of artists in Uruguay and beyond.

His use of pictograms within a structured grid has been seen by some art historians as a precursor or parallel to the work of certain North American artists like Adolph Gottlieb, who also explored symbolic forms derived from myth and the subconscious in the 1940s, although direct influence is debated.

Beyond his visual art, Torres-García was a prolific writer and theorist, leaving behind numerous books, articles, and manifestos that continue to be studied. He successfully bridged the perceived gap between European avant-garde centers and the developing art scenes of the Americas, acting as a vital conduit for ideas flowing in both directions. His work demonstrated that modern art could be both internationally relevant and deeply rooted in local identity.

Conclusion

Joaquín Torres-García was a visionary artist, a profound thinker, and a dedicated educator. His life's work was a testament to the power of synthesis – merging abstraction and figuration, reason and intuition, the ancient and the modern, the local and the universal. Through Constructive Universalism and the enduring legacy of the Taller Torres-García, he not only carved a unique path within modernism but also fundamentally enriched the artistic landscape of Latin America and contributed a vital chapter to the global history of art. His structured yet deeply symbolic compositions continue to resonate, inviting viewers into a world ordered by intellect and animated by a universal human spirit.