John Faed stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century Scottish art. Born into a family brimming with artistic talent, he carved out a distinct path, focusing primarily on the rich tapestry of Scottish history, literature, and rural life. His meticulous technique, honed through early work in miniature painting, combined with a deep connection to his homeland, resulted in works that resonated with Victorian audiences and continue to offer valuable insights into the cultural identity of Scotland during his time. While perhaps overshadowed in popular recognition by his younger brother Thomas, John Faed's contributions as a painter, academician, and member of the Scottish art community remain noteworthy.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Galloway

John Faed was born in 1819 (though some sources cite 1820) in Barlay Mill, near Gatehouse of Fleet in the historic county of Kirkcudbrightshire, Galloway, Scotland. He was the eldest son of James Faed Sr., a man of diverse talents working as a farmer, millwright, and engineer, who also possessed a keen interest in art. This paternal encouragement played a crucial role in nurturing the artistic inclinations evident in several of his children. The Galloway region, with its rolling hills, dramatic coastline, and strong local traditions, provided a formative backdrop for the young artist.

Faed's artistic promise emerged remarkably early. By the age of nine, he was already demonstrating a proficiency in drawing and had begun creating miniature portraits. This delicate and demanding art form requires exceptional control and attention to detail. His talent quickly gained local recognition. At the tender age of eleven, he undertook a commission to paint a series of miniature portraits for local dignitaries, a testament to his precocious skill and burgeoning reputation within his community.

During these formative years, he received guidance from William Campbell of Ard Gaten, who instructed him in the techniques of painting miniatures on ivory. Further support came from the local aristocracy, notably through the patronage of Lord Kenmure. This early encouragement and practical instruction were vital, providing Faed with both the skills and the confidence to pursue art more seriously, despite the lack of formal art academies in his immediate vicinity. His early success in miniature painting would leave a lasting imprint on his later work, evident in the careful detail and finish of his larger canvases.

Edinburgh and Academic Foundations

Seeking broader opportunities and more formal training, John Faed moved to Edinburgh in 1841. The Scottish capital was a vibrant centre for the arts and intellectual life, offering exposure to established artists and institutions. He enrolled as a student at the prestigious Trustees' Academy, the foremost art school in Scotland at the time. Founded to improve the quality of design in manufacturing, it had evolved into a crucial training ground for fine artists, numbering luminaries like Sir David Wilkie and Sir Henry Raeburn among its former students.

At the Trustees' Academy, Faed would have honed his drawing skills, studied from casts of classical sculpture, and likely received instruction in oil painting techniques. This period was crucial for transitioning from the intimate scale of miniatures to the larger formats and broader subjects of academic painting. He began exhibiting his work, primarily portraits and miniatures initially, which helped establish his reputation in the city's competitive art scene.

His talent did not go unnoticed by the artistic establishment. In 1847, John Faed was elected an Associate of the Royal Scottish Academy (ARSA), a significant mark of recognition from his peers. Just four years later, in 1851, he achieved the status of a full Academician (RSA), cementing his position within the Scottish art world. Membership in the RSA provided exhibition opportunities, prestige, and fellowship with other leading Scottish artists like Horatio McCulloch, the renowned landscape painter, and Sir William Allan, known for his historical scenes.

Themes and Subjects: Weaving Scottish Narratives

John Faed's artistic output is characterized by its strong thematic focus on Scotland. He drew inspiration from the nation's history, its rich literary tradition, its distinctive landscapes, and the everyday lives of its people. His work often carried narrative weight, telling stories or evoking specific moods and moments drawn from cultural sources. This aligned well with the Victorian appetite for anecdotal and illustrative painting.

Literature was a particularly fertile ground. Faed frequently turned to the works of Scotland's national poet, Robert Burns. His painting The Cotter's Saturday Night, based on Burns's famous poem, vividly depicts a humble rural family gathered for evening worship, capturing the piety and domesticity celebrated in the text. He also found inspiration in the historical novels of Sir Walter Scott, whose tales of Scotland's past were immensely popular. Works like Catherine Seyton and Roland Graeme brought characters from Scott's The Abbot to life on canvas.

Shakespearean themes also featured in his repertoire, reflecting the Bard's enduring influence across Britain. Paintings such as Olivia and Viola from Twelfth Night demonstrate his engagement with classic English literature alongside Scottish sources. Furthermore, traditional Scottish ballads and folklore provided narratives rich in romance, tragedy, and adventure, which Faed translated into visual form. Religious subjects, such as the Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, also appeared, treated with the seriousness and dramatic flair typical of the era's history painting.

Beyond literary and historical themes, Faed excelled at genre painting, depicting scenes of Scottish rural life, often with a sentimental touch. His portraits, while perhaps less central to his fame than his narrative works, were also an important part of his practice throughout his career.

Artistic Style and Technique

John Faed's style can be broadly situated within the Victorian mainstream, blending elements of Realism with a lingering Romantic sensibility. His early training as a miniaturist instilled a meticulous approach to detail. Faces, clothing, and background elements are often rendered with careful precision, giving his paintings a high degree of finish. This detailed realism was highly valued by contemporary audiences.

His compositions are typically well-structured, designed to clearly convey the narrative or focus attention on the main figures. He demonstrated skill in arranging complex figure groups, as seen in works like The Wappenshaw. There is often a theatrical quality to his scenes, with figures posed expressively to communicate emotion or advance the story. However, sources suggest he aimed for a certain naturalism, avoiding excessive flamboyance or purely decorative effects, instead focusing on conveying the emotional core of the scene through competent drawing and colouring.

His colour palette is generally rich but controlled, appropriate to the subject matter, whether it be the sober tones of a domestic interior or the brighter hues required for historical pageantry. He balanced the rendering of figures with their settings, ensuring that backgrounds supported rather than overwhelmed the central action. While not an innovator in the mould of the later Impressionists like fellow Scot William McTaggart, Faed was a highly competent craftsman working within the established conventions of his time, creating works that were both technically accomplished and emotionally engaging for his audience. His style contrasts with the more radical intensity and symbolism of the Pre-Raphaelites, such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti or William Holman Hunt, adhering more closely to the traditions established by earlier British narrative painters like Sir David Wilkie.

Major Works: Highlights of a Career

Several key paintings stand out in John Faed's oeuvre, showcasing his thematic interests and technical skill. The Wappenshaw (also spelled Wapinschaw), exhibited in 1862, is often considered one of his most important works. Depicting an assembly for a traditional Scottish shooting match or military muster, it is a complex multi-figure composition capturing a sense of community and historical tradition. The painting was well-received and acquired by a Member of Parliament, indicating its contemporary success. It exemplifies his ability to handle large-scale historical genre subjects.

The Cotter's Saturday Night, illustrating Robert Burns's poem, remains one of his most recognized works due to its subject matter's enduring appeal. It taps into themes of family, faith, and rural simplicity that resonated deeply in Victorian Scotland. The careful rendering of the figures and the humble interior creates an atmosphere of quiet devotion. This work, like many popular Victorian paintings, was likely reproduced as an engraving, further spreading its fame.

Annie's Tryst is another well-regarded painting, showcasing his ability to capture romantic and potentially poignant moments derived from Scottish ballads or literature. The title suggests a secret meeting or rendezvous, allowing Faed to explore themes of love and perhaps anxiety or anticipation through the expressions and postures of his figures.

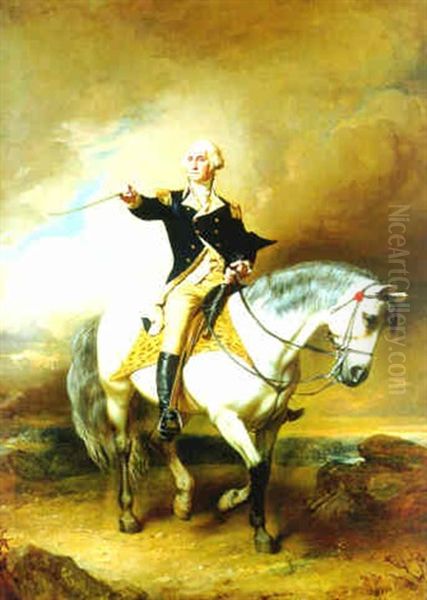

Other notable works include Catherine Seyton and Roland Graeme, demonstrating his engagement with Sir Walter Scott's novels, and the biblical scene Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. His portraiture, though less discussed, formed a consistent part of his output; an early example includes a copy of Gilbert Stuart's famous Portrait of George Washington. Works like The Gatekeeper, The Philosopher, and The Family Supper (mentioned in the initial user query) also contribute to his reputation as a painter skilled in character study and domestic scenes. Many of his works can be found in major collections, including the National Galleries of Scotland.

London Years and Exhibitions

While deeply rooted in Scotland, John Faed, like many ambitious artists of his time, also spent a significant period working in London. The capital offered a larger art market, greater opportunities for patronage, and the chance to exhibit at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts (RA). Moving to London allowed artists to engage with a wider circle of contemporaries and potentially achieve national recognition. His brother, Thomas Faed, achieved considerable success in London, becoming a full member of the Royal Academy (RA).

John Faed exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy in London over many years. Records indicate he showed a substantial number of works there, potentially over 240 paintings throughout his career, encompassing his characteristic mix of historical subjects, literary illustrations, genre scenes, and portraits. Exhibiting at the RA placed his work alongside that of the leading figures of the British art establishment, such as the President of the RA Frederic Leighton, the popular painter of modern life William Powell Frith, the master animal painter Sir Edwin Landseer, and the classical revivalist Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

This London period exposed Faed's work to a broader audience and critical reception. While he maintained his focus on Scottish themes, his time in London situated him within the wider context of British Victorian art. The competition was fierce, with established portraitists like Sir Joshua Reynolds and Sir Thomas Lawrence having set high standards in earlier generations, and contemporaries vying for commissions and critical acclaim. Despite this competitive environment, Faed maintained a steady presence through his regular contributions to the major exhibitions.

The Faed Family Legacy

The Faed family holds a unique place in Scottish art history, representing a remarkable concentration of artistic talent within one generation. John, as the eldest, was the first to pursue art professionally, paving the way for his younger siblings. His success undoubtedly encouraged the others.

His brother Thomas Faed (1826-1900) became arguably the most famous of the siblings, particularly in England. Thomas followed John to Edinburgh and studied at the Trustees' Academy. He later moved to London and achieved great popularity with his sentimental depictions of Scottish rural life, such as The Mitherless Bairn. He became an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1861 and a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1864. While John and Thomas often explored similar themes, Thomas's work perhaps had a broader, more immediate emotional appeal that captured the Victorian public's imagination.

Another brother, James Faed Jr. (1821-1911), distinguished himself primarily as an engraver, although he also painted. He produced fine mezzotint engravings after paintings by prominent artists, including his own brothers John and Thomas, as well as portraits by Sir Henry Raeburn and landscapes. His skill in translating paintings into prints was crucial in disseminating the images created by his brothers and others, making their work accessible to a much wider audience through affordable reproductions.

A sister, Susan Bell Faed (1827-1909), was also a painter, exhibiting works, though she is less well-known than her brothers. The collective artistic output of the Faed siblings represents a significant contribution to 19th-century Scottish and British art, particularly in the realm of genre painting and the depiction of Scottish life and culture. Their shared background in Galloway and their interconnected careers in Edinburgh and London form a compelling family narrative within art history.

Contemporaries and Context in Scottish and British Art

To fully appreciate John Faed's career, it's essential to place him within the context of his contemporaries. In Scotland, he followed in the tradition of Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841), whose detailed and anecdotal paintings of Scottish life had achieved international fame earlier in the century. Faed and his brother Thomas adapted Wilkie's model for the Victorian era. Other prominent Scottish contemporaries included the landscape painter Horatio McCulloch (1805-1867), known for his dramatic Highland scenes, and Sir William Allan (1782-1850), who specialized in historical subjects, particularly from Russian and Scottish history, and served as President of the RSA.

Sir Joseph Noel Paton (1821-1901), a near-exact contemporary, explored historical, allegorical, and fairy subjects with intricate detail, offering a different flavour of Victorian narrative art. Later in Faed's career, William McTaggart (1835-1910) emerged, moving towards a looser, more impressionistic style, particularly in his seascapes, signalling a shift away from the detailed narrative approach favoured by Faed.

In the broader British context, Faed worked during the heyday of Victorian painting. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848 by John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, challenged academic conventions with their emphasis on bright colours, intricate detail, and serious subjects, though their style and intensity differed from Faed's more traditional approach. William Powell Frith (1819-1909), Faed's exact contemporary, achieved immense success with large-scale panoramas of modern life like Derby Day and The Railway Station.

Animal painting, mastered by Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873), was hugely popular. The classical and aesthetic tendencies were represented by figures like Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) and Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912). Earlier masters of portraiture like Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) and Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), and the miniature tradition exemplified by artists like Richard Cosway (1742-1821) and Andrew Robertson (1777-1845), formed part of the historical backdrop against which Faed and his contemporaries operated. Faed navigated this complex scene, maintaining his focus on Scottish subjects while participating in the major London exhibitions.

Return to Galloway and Later Life

Despite his time spent in Edinburgh and London, John Faed maintained a deep affection for his native Galloway throughout his life. The landscapes and communities of Kirkcudbrightshire remained a source of inspiration and personal connection. In 1868, he demonstrated his commitment to the area by building a substantial house, Ardmore, in Gatehouse of Fleet, the town near his birthplace.

Around 1880, he decided to leave the bustle of London and retire permanently to Gatehouse of Fleet. This return allowed him to spend his later years immersed in the familiar surroundings that had shaped his youth. His presence contributed to the growing reputation of the Kirkcudbright area as an artists' haven. While the full flowering of the "Kirkcudbright School" of artists, including figures like E.A. Hornel and Charles Oppenheimer, occurred slightly later, Faed was an important early figure associated with the artistic life of the region.

His later years were spent painting, engaging with the local community, and enjoying the relative tranquility of Galloway compared to London. He continued to paint, though perhaps less prolifically than in his prime. His decision to return underscores the strong sense of regional identity that permeates much of his work. He passed away at his home, Ardmore, on 22 October 1902, leaving behind a significant body of work rooted in the culture and landscape of Scotland.

Legacy and Reputation

John Faed's legacy lies primarily in his contribution to Scottish art, particularly his dedication to depicting national themes drawn from history, literature, and everyday life. He was a skilled practitioner of the detailed, narrative style favoured in the Victorian era. His works provided his contemporaries with relatable and often sentimental images that celebrated Scottish identity and tradition.

While his brother Thomas achieved greater fame and financial success, particularly on the London stage, John maintained a respected position within the Scottish art establishment throughout his long career, evidenced by his early election to the Royal Scottish Academy. His extensive exhibition record at both the RSA in Edinburgh and the RA in London demonstrates his consistent productivity and engagement with the main art institutions of his day.

The popularity of engravings after his paintings, often produced by his brother James Faed Jr., helped to disseminate his images widely, making his work familiar to a broad public beyond the galleries. Today, his paintings are valued for their technical accomplishment, their historical and literary associations, and the insight they offer into 19th-century Scottish culture and Victorian taste. He remains an important figure in the story of Scottish art, representing a bridge between the era of Wilkie and the later developments of the Glasgow Boys and Scottish Colourists. His dedication to his craft and his homeland ensures his place in the annals of British art.

Conclusion

John Faed's life spanned a period of significant change in Britain and in the art world. From his beginnings as a talented boy miniaturist in rural Galloway to becoming an established Academician exhibiting in Edinburgh and London, he built a career centred on his love for Scotland. Through subjects drawn from Burns, Scott, history, and the life of ordinary Scottish people, he created a body of work that captured the imagination of his Victorian audience. As a painter, a member of a remarkable artistic family, and a figure connected to the burgeoning art scene in Kirkcudbright, John Faed left an indelible mark on the cultural heritage of Scotland. His paintings continue to be appreciated for their narrative detail, historical interest, and heartfelt connection to his native land.