John Flaxman, born in York on July 6, 1755, and passing away in London on December 7, 1826, stands as a pivotal figure in British art history. Primarily celebrated as a sculptor, he was also a highly influential draughtsman, designer, and illustrator whose work profoundly shaped the Neoclassical movement not only in Britain but across Europe. His artistic output, characterized by its elegant linearity, classical restraint, and moral seriousness, marked a distinct shift away from the more exuberant styles preceding it, establishing a benchmark for grace and intellectual depth in the visual arts of his time.

Flaxman's journey from the son of a humble plaster cast maker to the first Professor of Sculpture at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts is a testament to his innate talent, relentless self-improvement, and deep engagement with the artistic and intellectual currents of his era. His legacy endures through his numerous public monuments, delicate relief designs, and, perhaps most widely, his seminal outline illustrations for classical literature.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

John Flaxman's entry into the world was marked by physical frailty, a condition that would persist throughout his life. Born in York, he spent his earliest years in a city rich with history, but his family soon returned to London. His father, also named John, ran a business making and selling plaster casts, often replicas of classical sculptures. This environment provided the young Flaxman with his first, albeit informal, art education. Surrounded by these forms from antiquity, he developed an early fascination with drawing and modelling.

Despite his delicate health limiting formal schooling, Flaxman was an avid reader and autodidact. He immersed himself in classical literature, translating Homer and other ancient authors, which deeply informed his artistic sensibilities from a young age. His father's shop near Covent Garden became a hub for artists and connoisseurs, exposing the young boy to the vibrant London art scene. Recognizing his son's talent, the elder Flaxman encouraged his artistic pursuits.

By the age of twelve, John was already winning prizes for his models from the Society of Arts. At fifteen, in 1770, he enrolled as a student at the newly established Royal Academy Schools. Here, he further honed his skills and formed crucial friendships with fellow students who would also achieve fame, most notably the visionary poet and artist William Blake and the painter Thomas Stothard. Though he won a silver medal in 1771, he famously failed to win the gold medal the following year, a disappointment attributed by some to the preference of the Academy's president, Sir Joshua Reynolds, for a rival candidate. This setback, however, did not deter his ambition.

The Wedgwood Connection

A significant turning point in Flaxman's early career came in 1775 when he began working for the renowned potter Josiah Wedgwood. Wedgwood, a pioneering industrialist and astute businessman, was keen to elevate the artistic quality of his ceramic wares, particularly his new Jasperware, by employing talented artists to create designs inspired by classical antiquity. Flaxman proved to be an ideal collaborator.

For over a decade, Flaxman supplied Wedgwood with a steady stream of designs, primarily for bas-reliefs used to decorate vases, plaques, cameos, and chimneypieces. His work drew heavily on ancient Greek and Roman motifs, mythology, and literature. He adapted figures from Greek vase paintings and Roman sarcophagi, translating them into elegant, low-relief compositions perfectly suited for Wedgwood's materials.

Among his most famous designs for Wedgwood are The Dancing Hours, The Apotheosis of Homer, and various mythological scenes and portraits. This work was crucial for Flaxman's development. It forced him to refine his understanding of composition in relief and master the expressive potential of pure line, stripping away extraneous detail to focus on clarity and grace. The widespread commercial success of Wedgwood's products also meant that Flaxman's designs reached a broad international audience, significantly contributing to the popularization of the Neoclassical aesthetic and establishing his reputation long before he undertook major sculptural commissions.

Roman Sojourn and Artistic Maturity

In 1787, financed partly by Wedgwood, Flaxman and his wife Ann Denman (whom he had married in 1782) embarked on a journey to Rome, the ultimate destination for any aspiring Neoclassical artist. Initially planned as a shorter study trip, their stay extended to seven years, a period of intense study and significant artistic production that proved transformative for his career. Rome offered unparalleled opportunities to study firsthand the masterpieces of classical sculpture and Renaissance art.

Flaxman immersed himself in the study of ancient Roman and Greek sculptures in the city's collections and ruins. He also deeply admired the works of Renaissance masters like Michelangelo and Raphael, absorbing lessons in composition and anatomical representation. Unlike many British artists on the Grand Tour who focused primarily on painting, Flaxman dedicated himself to understanding the principles of sculpture, filling sketchbooks with drawings and observations.

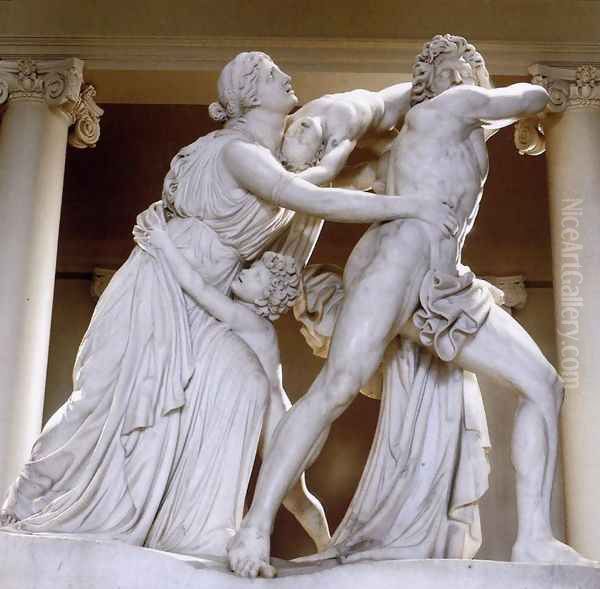

During his time in Rome, Flaxman received several important commissions. He began work on a large marble group, The Fury of Athamas, for the Earl of Bristol. He also undertook monumental tomb designs, such as the memorial to the painter Thomas Collins in Chichester Cathedral, which showcased his developing style in funerary sculpture. However, the most influential works produced during his Roman period were arguably his outline illustrations.

Commissioned by discerning patrons like Mrs. Hare-Naylor for Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, Thomas Hope for Dante's Divine Comedy, and later Countess Spencer for Aeschylus, these illustrations were conceived as simple line engravings. Executed with minimal shading and modelling, they focused entirely on the purity of contour to convey narrative, form, and emotion. This radical simplicity, inspired by Greek vase painting and perhaps early Italian engravings, was revolutionary and garnered immediate international acclaim upon publication.

The Neoclassical Style of John Flaxman

John Flaxman is considered one of the leading exponents of Neoclassicism in Britain. This artistic movement, which flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, sought inspiration from the art and culture of ancient Greece and Rome, emphasizing order, clarity, rationality, and moral virtue in contrast to the perceived frivolity of the preceding Rococo style. Flaxman's interpretation of Neoclassicism was distinct, characterized by its profound emphasis on line, grace, and emotional restraint.

His style was fundamentally linear. Whether in sculpture, relief, or drawing, the contour, the outline of the form, was paramount. He believed that the purest expression of beauty lay in the elegance and flow of line, a principle derived from his close study of Greek vase painting and antique gems. This resulted in works that often possess a delicate, almost ethereal quality, prioritizing harmony and rhythm over dramatic chiaroscuro or complex textures.

Flaxman's Neoclassicism was also deeply imbued with a sense of moral purpose and sentiment. His figures, often drawn from mythology, classical literature, or Christian scripture, convey virtues such as piety, grief, heroism, and maternal love with quiet dignity. While sometimes criticized for a lack of physical vigour or intense passion compared to continental contemporaries like Jacques-Louis David or Antonio Canova, Flaxman excelled at expressing tender emotions and spiritual states through subtle gestures and harmonious compositions.

His influences were diverse but centred on the classical. The Parthenon sculptures (known then primarily through casts and drawings before the arrival of the Elgin Marbles in London) were a key inspiration. Italian Renaissance artists, particularly the early masters of relief like Donatello and Lorenzo Ghiberti, also informed his work. Furthermore, Flaxman possessed an unusual appreciation for Gothic art, admiring its linearity and spiritual intensity, elements which subtly inflected his own Neoclassical style, lending it a unique character within the broader European movement.

Masterpieces of Sculpture and Design

Upon his return to England in 1794, Flaxman's reputation, bolstered by his Roman studies and the success of his illustrations, positioned him as a leading sculptor. He embarked on a prolific period, creating numerous public monuments, funerary sculptures, and other works that solidified his status.

His funerary monuments constitute a significant portion of his sculptural output and are found in churches and cathedrals across Britain, including Westminster Abbey and St Paul's Cathedral. These works typically feature allegorical figures representing grief, faith, or resurrection, often accompanying portrait medallions or figures of the deceased. Notable examples include the monument to the naval hero Earl Howe (St Paul's), the monument to the poet William Collins (Chichester Cathedral), and the poignant monument to Agnes Cromwell (Chichester Cathedral), praised for its tender depiction of maternal piety. These works epitomize his gentle, linear style and his ability to convey sincere emotion through restrained classical forms.

Among his most ambitious public commissions was the monument to Admiral Lord Nelson in St Paul's Cathedral (completed 1818). While perhaps less dynamic than some contemporary memorials, it presents a dignified composition featuring Nelson, Britannia, and various allegorical figures, embodying the nation's grief and pride. Another significant work is the large monument to William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, in Westminster Abbey, which showcases his skill in composing complex figural groups within an architectural framework.

Beyond large-scale monuments, Flaxman continued to produce designs for Wedgwood and also created models for silverwork for firms like Rundell, Bridge & Rundell, demonstrating the versatility of his Neoclassical style across different media. His earlier designs, like The Apotheosis of Homer, remained popular and continued to be reproduced, cementing their place as icons of Neoclassical design. The Fury of Athamas, completed after his return from Rome, stands as one of his few large, free-standing mythological groups in marble.

Illustrating the Classics

While Flaxman achieved considerable fame as a sculptor, his outline illustrations arguably had an even wider and more immediate international impact. The series he created in Rome for Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, Aeschylus's tragedies, and Dante's Divine Comedy revolutionized book illustration and profoundly influenced artists across Europe for generations.

These illustrations were executed as pure outlines, intended for engraving by artists like Tommaso Piroli in Rome. They deliberately eschewed shading, perspective, and atmospheric effects, focusing instead on the expressive power of the contour line. This minimalist approach was radical for its time. It aimed to capture the simplicity and grandeur Flaxman perceived in ancient Greek art, particularly vase painting, and translate it to the page. The figures are often arranged frieze-like, emphasizing clarity of narrative and idealized form.

Published initially in Rome and then widely disseminated across Europe, these engravings were immensely popular. They appealed to the Neoclassical taste for clarity, simplicity, and classical themes. Artists saw in them a new way of representing form and narrative, stripped bare of academic conventions. Figures like Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres in France were known admirers and drew inspiration from Flaxman's linear style. German Romantics also responded to their perceived purity and spirituality. Even artists with vastly different sensibilities, such as Francisco Goya in Spain and William Blake in England, engaged with Flaxman's illustrations, absorbing lessons in linear expression and composition.

Flaxman's illustrations are often cited as precursors to modern graphic styles, including comic art, due to their emphasis on line and sequential narrative. They demonstrated that complex stories and emotions could be conveyed effectively through simplified, elegant contours, leaving a lasting legacy on the art of illustration and graphic design.

Academic Recognition and Teaching

Flaxman's growing reputation following his return from Rome led to official recognition from Britain's premier artistic institution. In 1797, he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA), and in 1800, he achieved the status of full Academician (RA). This membership cemented his position within the British art establishment.

A decade later, in 1810, the Royal Academy established a dedicated Professorship of Sculpture, and John Flaxman was unanimously chosen as its first occupant. This was a significant appointment, reflecting the increasing status of sculpture within the Academy and the nation's artistic life. Flaxman took his duties seriously, preparing a series of ten lectures covering the history and principles of sculpture.

His lectures traced the history of sculpture from ancient Egypt through Greece and Rome, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance, culminating in a discussion of British sculpture. They emphasized the importance of studying anatomy, understanding classical principles of beauty and proportion, and imbuing sculpture with moral and intellectual content. Delivered annually at the Academy, these lectures influenced generations of students and helped to shape the direction of British sculpture in the early 19th century.

Though not published until after his death, Flaxman's lectures provide valuable insight into his artistic philosophy and his deep knowledge of art history. His role as Professor of Sculpture underscored his authority as a leading figure in Neoclassicism and his commitment to educating future artists in its principles.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Throughout his career, John Flaxman maintained relationships with many of the leading artists, writers, and patrons of his day. His gentle nature and intellectual inclinations made him a respected figure in London's cultural circles.

His lifelong friendship with William Blake is particularly noteworthy. Despite their vastly different artistic temperaments – Flaxman's calm classicism contrasting with Blake's fiery visionary Romanticism – they shared a deep mutual respect and common interests in literature, spirituality (both were drawn to the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg), and the potential of linear expression. Flaxman was an early supporter of Blake, commissioning work from him and introducing him to potential patrons. Their correspondence reveals a warm, albeit sometimes complex, relationship.

He was also close to the painter Thomas Stothard, another fellow student from the Royal Academy Schools. They shared an interest in literary illustration and classical themes. Flaxman collaborated closely with Josiah Wedgwood, maintaining a professional relationship even after his return from Rome. He also interacted with other prominent Royal Academicians, including the Swiss-born painter Henry Fuseli, whose dramatic and often unsettling style offered a stark contrast to Flaxman's own, yet both shared a fascination with literary and mythological subjects. He was acquainted with portraitists like George Romney, who admired his work.

Flaxman's patrons included influential figures like the collector Thomas Hope, who commissioned the Dante illustrations, and members of the aristocracy who commissioned funerary monuments. His international reputation also brought him into contact or correspondence with leading European artists, including the celebrated Italian sculptor Antonio Canova, whom he met in Rome and whose work shared certain Neoclassical affinities with his own, though Canova's style often possessed a greater sensuousness. The Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen was another major contemporary Neoclassicist working in Rome whose path likely crossed with Flaxman's circle.

Personal Life, Character, and Anecdotes

John Flaxman married Ann Denman in 1782. Their marriage appears to have been a happy and supportive partnership. Ann accompanied him to Rome and managed their household affairs, allowing Flaxman to focus on his art. Her death in 1820 was a severe blow to him, casting a shadow over his final years. They had no children. After Ann's death, Flaxman's household was managed by his younger sister, Mary Ann Flaxman, and his sister-in-law, Maria Denman, both of whom were also artists to some degree.

Contemporaries described Flaxman as modest, pious, industrious, and kind-hearted. He was deeply religious, adhering to the teachings of the Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg, whose doctrines emphasized spirituality, divine order, and the correspondence between the physical and spiritual worlds. This faith undoubtedly informed the serene and often spiritual quality of his art.

Despite his professional success, Flaxman lived relatively simply. His lifelong physical frailty persisted, and he suffered from various ailments. Anecdotes often emphasize his gentle demeanor and dedication to his work. While highly respected, his art was not without its critics. Some contemporaries found his style too austere, lacking in anatomical power or emotional intensity, particularly when compared to the more dramatic works emerging from continental Europe. His reliance on established compositional formulas in his funerary monuments also drew occasional criticism for repetitiveness.

His failure to win the Royal Academy's gold medal as a student remained a remembered incident, sometimes cited as an early sign of academic conservatism or perhaps Flaxman's own limitations in certain types of competition pieces at that stage. Nevertheless, his career trajectory demonstrated a remarkable ascent based on talent, study, and a clear artistic vision. He died relatively suddenly in December 1826 after a short illness, likely related to his chronic respiratory problems, and was buried in the churchyard of St Giles-in-the-Fields, London.

Enduring Legacy and Influence

John Flaxman's influence on the art of his time and subsequent generations was profound and multifaceted. As a sculptor, he was the dominant figure in British Neoclassicism, setting a standard for funerary monuments and public sculpture that emphasized grace, sentiment, and classical purity. His works adorn major national sites like St Paul's Cathedral and Westminster Abbey, serving as enduring examples of the Neoclassical style in Britain.

His impact as an illustrator and designer was perhaps even more far-reaching. The outline engravings for Homer, Aeschylus, and Dante achieved phenomenal international success, influencing countless artists across Europe and America. They provided a potent model for linear expression and classical interpretation, impacting figures as diverse as David, Ingres, Goya, the German Romantics, and even later artists associated with the Aesthetic Movement and Art Nouveau, who admired the purity of his line. His work for Wedgwood popularized Neoclassical motifs and demonstrated how high artistic standards could be applied to industrial production.

Flaxman's role as the first Professor of Sculpture at the Royal Academy allowed him to shape sculptural education and theory in Britain. His lectures and teachings promoted the ideals of Neoclassicism and influenced students who carried these principles into the Victorian era. While his style eventually fell out of fashion with the rise of Romanticism's more dramatic and emotional modes, and later modernist movements, his historical importance remained recognized.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, there has been a renewed appreciation for Flaxman's elegant draughtsmanship, the innovative nature of his illustrations, and his significant contribution to the Neoclassical movement. Collections of his drawings and models, notably at University College London (home to the Flaxman Gallery housing many of his plaster models) and the Royal Academy, continue to be studied. He remains a key figure for understanding the transition from Georgian to Regency art in Britain and the broader European phenomenon of Neoclassicism.

Conclusion

John Flaxman occupies a unique and significant place in the history of art. He successfully navigated the worlds of fine art sculpture, commercial design, and academic teaching. His unwavering commitment to the ideals of classical beauty, expressed through a distinctively pure and linear style, made him a defining figure of Neoclassicism. Through his sculptures, reliefs, and revolutionary illustrations, he not only shaped the aesthetic sensibilities of his own time but also left a lasting legacy that resonated through subsequent artistic developments in Britain and beyond. His work continues to be admired for its elegance, intellectual depth, and the serene beauty of its refined contours.