Antonio Canova stands as a colossus in the annals of art history, a sculptor whose name is synonymous with the Neoclassical movement. Dominating European sculpture from the late 18th century until his death in the early 19th century, Canova's genius lay in his ability to imbue cold marble with a warmth, grace, and idealized beauty that harked back to classical antiquity, yet resonated profoundly with the sensibilities of his own era. His prolific output, technical virtuosity, and influential career left an indelible mark on the trajectory of Western art.

Early Life and Venetian Beginnings

Antonio Canova was born on November 1, 1757, in Possagno, a small village in the Republic of Venice, nestled at the foot of the Grappan Alps. His family background was steeped in the tradition of stone carving; his father, Pietro Canova, and his paternal grandfather, Pasino Canova, were both stonemasons of local repute. This early exposure to the craft undoubtedly shaped his destiny. Tragedy struck early when his father died when Antonio was just four years old. His mother, Angela Zardo, remarried shortly thereafter, and young Canova was largely raised by his grandfather, Pasino.

Pasino recognized the boy's prodigious talent. Anecdotes from his childhood abound, the most famous being the story of him sculpting a lion out of butter at a dinner party hosted by the Venetian senator Giovanni Falier. This display of skill, supposedly at the age of around seven or nine, impressed Falier, who would become an important early patron. Another tale recounts him carving two small marble shrines in the local style of Possagno at the tender age of nine, demonstrating a precocious mastery of the material.

Under his grandfather's tutelage, Canova learned the fundamentals of stone carving. His formal artistic education began in Venice, a city then past its political zenith but still a vibrant artistic center. Around 1768, he was apprenticed to Giuseppe Bernardi, also known as Torretti (a nephew of another sculptor, Giuseppe Torretti). Bernardi's workshop was a significant training ground, and Canova honed his skills there for several years. When Bernardi died in 1773, Canova began working with Giovanni Battista Torretti, Bernardi's nephew, further refining his technique and deepening his understanding of sculptural traditions.

During his Venetian period, Canova studied at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia, where he immersed himself in life drawing and the study of classical casts. His early works from this time, such as Orpheus and Eurydice (1775-1776), commissioned by his patron Senator Falier, already showed a departure from the prevailing Rococo style, hinting at the nascent Neoclassicism that would define his career. He won a gold medal from the Venice Academy in 1777, and his sculpture Daedalus and Icarus (1778-1779), exhibited in 1779, garnered significant acclaim for its naturalism and emotional poignancy, securing his reputation in Venice.

The Call of Rome and Rise to Prominence

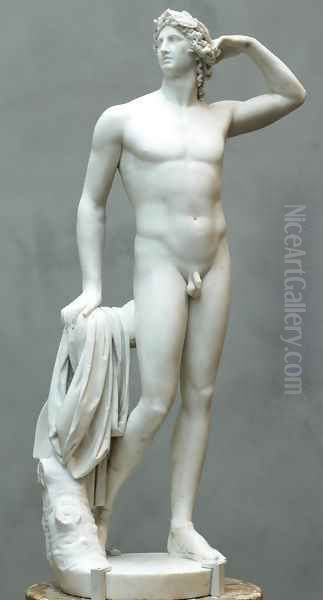

The year 1779 marked a pivotal moment in Canova's life. With the proceeds from Daedalus and Icarus and support from patrons, he embarked on a journey to Rome, the epicenter of the classical world and the burgeoning Neoclassical movement. Rome was a revelation. He diligently studied the masterpieces of antiquity – the Apollo Belvedere, the Laocoön, and countless others – and absorbed the theories of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the German art historian whose writings championed the "noble simplicity and quiet grandeur" of Greek art. He also encountered contemporary artists working in the Neoclassical vein, such as the painter Anton Raphael Mengs, though Mengs died shortly after Canova's arrival.

In Rome, Canova's talent quickly gained recognition. He was befriended by Gavin Hamilton, a Scottish Neoclassical painter and archaeologist, who became an important mentor and promoter of his work. Hamilton introduced him to a wider circle of influential figures, including potential patrons among the British aristocracy on their Grand Tour.

His first major Roman commission, Theseus and the Minotaur (1781-1783), was a resounding success. Instead of depicting the violent struggle, Canova chose the moment after the battle, with Theseus seated contemplatively on the slain Minotaur. This choice, emphasizing psychological depth and calm over dramatic action, was a hallmark of Neoclassical ideals and established Canova as a leading figure of the new movement. The work was lauded for its technical perfection and its embodiment of classical restraint.

The Apex of Neoclassicism: Canova's Style

Canova's style became the epitome of Neoclassicism in sculpture. He rejected the theatricality and ornate exuberance of the Baroque, exemplified by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and the frivolous charm of the Rococo. Instead, he sought a purity of form, an idealized beauty, and a refined elegance inspired by ancient Greek and Roman art. His figures are characterized by smooth, highly polished surfaces, graceful lines, and a sense of serene detachment.

A key aspect of Canova's working method was his meticulous process. He would begin with numerous preparatory drawings, followed by small clay models (bozzetti), then full-scale plaster models. These plaster models were often his definitive artistic statement, marked with points (repère marks) that his skilled assistants would use to transfer the design to the marble block. Canova himself, however, was renowned for applying the "ultima mano" – the final touch – personally carving the delicate surface details and achieving the characteristic soft, almost translucent finish that made his marble figures seem to breathe. He often treated the marble with a special patina or wax to soften the glare and enhance the subtlety of the forms, sometimes even exhibiting works by candlelight to accentuate their ethereal quality.

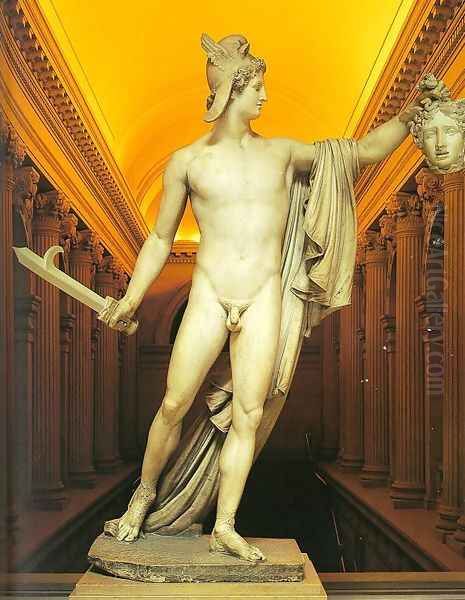

His subjects were frequently drawn from classical mythology, such as the tender and celebrated Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss (1787-1793), a masterpiece of delicate eroticism and technical brilliance. Other mythological subjects included Venus and Adonis (1789-1794), Perseus with the Head of Medusa (1800-1801), which was intended to replace the Apollo Belvedere when it was taken to Paris by Napoleon, and Hercules and Lichas (1795-1815), a dynamic group depicting raw power and tragedy.

Masterpieces of Grace and Grandeur

Canova's oeuvre is vast, but several works stand out for their iconic status and artistic significance.

Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss is perhaps his most beloved work. Commissioned by Colonel John Campbell (later Lord Cawdor), it depicts the mythological moment when Cupid awakens the lifeless Psyche with a kiss. The composition is a marvel of interlocking forms, with the figures' limbs and wings creating a harmonious X-shape. The tenderness of the embrace, the delicate rendering of flesh, and the emotional intensity captured in a moment of serene grace make it a quintessential Neoclassical masterpiece. Two primary versions exist, one in the Louvre Museum, Paris, and another in the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

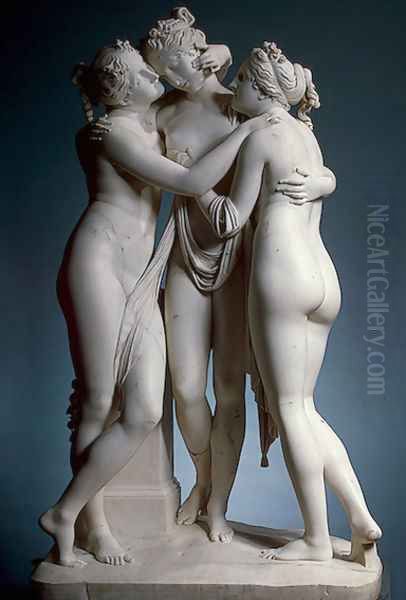

The Three Graces (1814-1817), commissioned by John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford (a version for Joséphine de Beauharnais was also made), is another iconic group. Depicting Aglaia, Euphrosyne, and Thalia, the personifications of charm, beauty, and creativity, the sculpture is celebrated for its lyrical beauty and harmonious composition. The figures, intertwined in a gentle embrace, embody ideal feminine grace and the Neoclassical pursuit of perfect form. The work showcases Canova's unparalleled ability to render soft flesh and flowing drapery in marble.

Canova also excelled in portraiture, though always filtered through a Neoclassical lens of idealization. His depiction of Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker (1803-1806) presents the French emperor as a colossal nude Roman deity, a heroic idealization that Napoleon himself reportedly found too athletic. More controversial was his statue of Napoleon's sister, Pauline Bonaparte as Venus Victrix (1805-1808). Depicting her reclining semi-nude on a couch, holding the apple of victory, the work caused a scandal but is admired for its sensuous beauty and classical allusion.

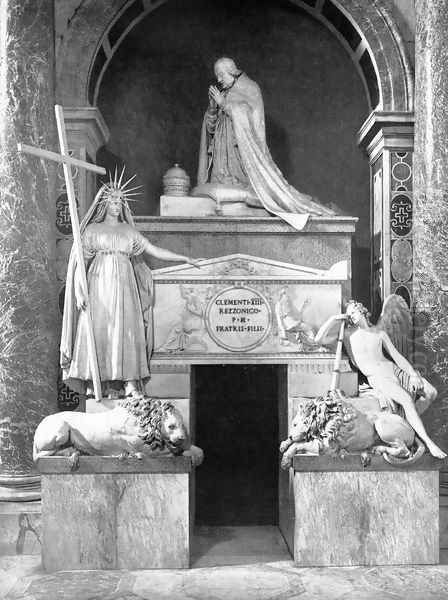

His funerary monuments are among his most powerful and influential creations. The Tomb of Pope Clement XIV (1783-1787) in Santi Apostoli, Rome, and the Tomb of Pope Clement XIII (1783-1792) in St. Peter's Basilica, established his reputation for monumental sculpture. These works, with their allegorical figures and dignified portrayals of the deceased, set a new standard for funerary art. The Funerary Monument to Maria Christina of Austria (1798-1805) in the Augustinian Church, Vienna, is particularly poignant, featuring a procession of mourning figures entering a pyramidal tomb, conveying a profound sense of loss and solemnity.

Other significant works include Apollo Crowning Himself (1781-1782), The Penitent Magdalene (versions from 1793-1796 and later, including the one known as the Burlington Magdalene), and the statue of George Washington (1816-1820), commissioned for the North Carolina State House, depicting the American president in the guise of a Roman general (sadly, this work was largely destroyed by fire in 1831, though fragments and models remain).

Patrons and International Acclaim

Canova's fame spread rapidly throughout Europe. He became the most sought-after sculptor of his time, receiving commissions from popes, emperors, kings, and wealthy aristocrats across the continent. His patrons included Pope Pius VI and Pope Pius VII, Napoleon Bonaparte and his family, Emperor Francis II of Austria, Tsar Alexander I of Russia, and numerous British nobles such as the Duke of Bedford and Lord Castlereagh.

His studio in Rome became a major attraction for visitors on the Grand Tour. He was admired not only for his artistic skill but also for his amiable personality and diplomatic acumen. He was elected to numerous prestigious art academies, including the Accademia di San Luca in Rome, where he eventually served as Principe (President) in 1810. In 1802, Pope Pius VII appointed him Inspector General of Antiquities and Fine Arts for the Papal States, a role in which he advocated for the preservation of artistic heritage. He was also made a Knight of the Golden Spur by the Pope.

His international reputation was such that he was often compared to the great sculptors of antiquity. His ability to navigate the complex political landscape of Napoleonic Europe, working for patrons on opposing sides, attests to his widespread appeal and the universal admiration for his art.

The Man Behind the Marble: Anecdotes and Character

Beyond his public persona as a celebrated artist, Canova was known for his diligence, generosity, and refined character. He maintained a large and highly organized workshop, employing numerous assistants to help with the laborious process of marble carving, yet always reserving the final, crucial stages for himself.

Anecdotes from his life offer glimpses into his personality. The story of the butter lion, whether entirely factual or embellished, highlights his early, almost intuitive, grasp of form. His relationship with his housekeeper, Luigia Giuli, was a subject of some speculation. One story, possibly apocryphal, suggests he destroyed a nearly completed statue after a quarrel with her, fearing public gossip that she might have posed nude for him. This hints at a sensitivity to public perception and a desire to maintain a decorous image.

Canova was also known for his philanthropy. He used his considerable wealth to support young artists, provide dowries for poor girls in Possagno, and contribute to charitable causes. His dedication to his native village remained strong throughout his life.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Canova did not work in a vacuum. He was part of a vibrant artistic milieu, interacting with, influencing, and sometimes competing with other prominent artists of the Neoclassical era.

Among sculptors, his chief rival was the Danish artist Bertel Thorvaldsen, who also worked in Rome. While their styles shared Neoclassical foundations, Thorvaldsen's work was often seen as more austere and rigorously classical, whereas Canova's was perceived as having a softer, more graceful, and sometimes more sensuous quality. Despite their rivalry, they maintained a degree of mutual respect.

Other contemporary sculptors included the Englishman John Flaxman, known for his elegant line drawings and relief sculptures, whom Canova admired and recommended for an academic position. Joseph Chinard in France, Lorenzo Bartolini in Italy (a student of Jacques-Louis David), Thomas Banks and Joseph Nollekens in Britain, and Johann Gottfried Schadow in Germany were also significant figures in Neoclassical sculpture, each contributing to the diverse expressions of the style. Canova also had academic exchanges with figures like the restorer and dealer Bartolomeo Cavaceppi and knew sculptors like Alexander Trippel.

In painting, Jacques-Louis David was the leading figure of French Neoclassicism, and his heroic and morally charged canvases paralleled Canova's sculptural ideals. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, a student of David, further developed the Neoclassical line and form. Other Neoclassical painters included Angelica Kauffman, a Swiss-Austrian artist popular in Rome and London; Pompeo Batoni, an Italian painter who was a precursor to the style; and Gavin Hamilton, whose history paintings and antiquarian interests aligned closely with Canova's. Canova also mentored younger artists, such as the English painter Sir George Hayter. Artists like Giuseppe Cades and Antonio Pinelli were also part of this Neoclassical wave.

Diplomat and Guardian of Heritage

One of Canova's most significant contributions beyond his own artistic production was his role as a cultural diplomat and advocate for the arts. After the fall of Napoleon in 1815, Pope Pius VII entrusted Canova with a delicate and crucial mission: to travel to Paris to negotiate the restitution of artworks looted from Rome and the Papal States by Napoleon's armies.

This was a challenging task, as many of these masterpieces, including the Apollo Belvedere and the Laocoön, had become prized possessions of the Louvre. Canova, leveraging his international prestige, diplomatic skills, and the support of British officials like Lord Castlereagh and William Richard Hamilton (then Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs), successfully argued for the return of many, though not all, of these treasures. This act significantly enhanced his reputation and earned him the title Marquis of Ischia from the Pope. He also played a role in preventing the further export of Italian art and facilitated the repurchase of works for Italian collections.

Later Years, Death, and the Tempio Canoviano

In his later years, Canova devoted much of his energy and personal fortune to a project in his beloved hometown of Possagno: the design and construction of a new parish church, the Tempio Canoviano. This remarkable building, designed by Canova himself with architectural assistance, combines elements of the Parthenon (the Doric portico) and the Pantheon (the domed rotunda), symbolizing his deep reverence for classical architecture. He intended it to be a church, a mausoleum for himself, and a gallery for his works (or at least their plaster models).

Antonio Canova died in Venice on October 13, 1822, at the age of 64, while overseeing work on the Tempio. His death was mourned throughout Europe. He received a grand funeral in Venice, and his body was interred in the Tempio Canoviano in Possagno, as he had wished. His heart, however, was placed in an urn in a porphyry pyramid – part of a funerary monument designed by his students based on his own monument to Maria Christina – in the Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in Venice. His right hand is preserved in the Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia.

His nephew, Giovanni Battista Sartori, inherited his estate and was instrumental in ensuring the completion of the Tempio and the transfer of Canova's plaster models, drawings, and studio contents to Possagno, where they form the core of the Museo Canova today.

Enduring Influence and Scholarly Reception

Canova's influence on subsequent generations of sculptors was immense, particularly during the first half of the 19th century. His idealized forms and technical perfection became the standard for academic sculpture across Europe and America. Artists like Hiram Powers and Horatio Greenough in the United States directly emulated his style.

However, by the mid-19th century, with the rise of Romanticism and Realism, Canova's reputation began to wane. Critics like Pietro Selvatico found his work too artificial, lacking the raw emotion or naturalism favored by newer artistic movements. For much of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as Modernism took hold, Neoclassicism in general, and Canova in particular, were often dismissed as cold, academic, and derivative.

The 20th century saw a gradual re-evaluation of Canova's work. Scholars and critics, including figures like Carlo Carrà in Italy, began to appreciate anew his technical mastery, the subtle sensuality of his surfaces, his innovative compositional solutions, and the genuine emotional depth present in many of his sculptures. Modern scholarship has explored various facets of his career: his studio practice, his innovative display techniques (using rotating bases and specific lighting to enhance the viewing experience), his role in the art market, and his complex relationship with patrons and power.

Today, Canova is firmly re-established as one of the greatest sculptors in Western art. Exhibitions of his work continue to draw large crowds, and scholarly interest remains high. His ability to synthesize classical ideals with a contemporary sensibility, to create works of both monumental grandeur and intimate tenderness, ensures his enduring appeal.

Conclusion

Antonio Canova was more than just a sculptor; he was a cultural phenomenon who defined an era. From his humble beginnings in Possagno to his international stardom in Rome, he navigated the turbulent tides of his time with grace and genius. His sculptures, characterized by their idealized beauty, technical perfection, and profound emotional resonance, revived the spirit of classical antiquity for a new age. As an artist, a diplomat, and a guardian of cultural heritage, Canova left a legacy that continues to inspire awe and admiration, securing his place as the undisputed master of Neoclassical sculpture and a pivotal figure in the history of art. His works remain timeless testaments to the enduring power of beauty and the transcendent capabilities of the artist's hand.