Introduction: A Victorian Polymath

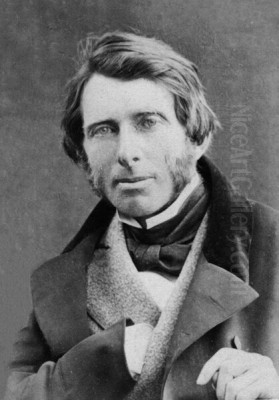

John Ruskin (1819-1900) stands as one of the most influential and complex figures of the Victorian era. A true polymath, his intellectual reach extended far beyond art criticism, encompassing geology, architecture, literature, education, social reform, political economy, and even botany and mythology. Born into a period of profound industrial, social, and cultural change in Britain, Ruskin became a powerful voice, shaping aesthetic tastes, challenging economic orthodoxies, and advocating for a more just and beautiful world. His writings, characterized by passionate prose and deeply held moral convictions, engaged directly with the pressing issues of his time, leaving an indelible mark on art, architecture, social thought, and environmental consciousness that continues to resonate today.

Ruskin’s life and work were driven by a fundamental belief in the interconnectedness of art, nature, and morality. He argued vehemently that a nation's art was an index of its ethical health and that the pursuit of beauty was inseparable from the pursuit of truth and goodness. He championed artists he believed embodied these principles and fiercely criticized those he saw as falling short. His legacy is vast and multifaceted, encompassing seminal works of art and architectural criticism, pioneering social commentary, and a lifelong dedication to education and the improvement of society.

Early Life and Formative Influences

John Ruskin was born in London on February 8, 1819, the only child of John James Ruskin, a prosperous sherry importer, and Margaret Cox Ruskin. His upbringing was privileged yet uniquely sheltered and intense. His father nurtured his son's artistic sensibilities, sharing his own love for literature and collecting contemporary watercolors, including works by J.M.W. Turner. His mother, a devout Evangelical Protestant, provided a strict religious education, focusing heavily on daily Bible readings. This immersion in the language and narratives of the King James Bible profoundly shaped Ruskin's prose style and his moral outlook throughout his life.

Educated largely at home by tutors, the young Ruskin displayed precocious talents in writing and drawing. Family travels across Britain and, significantly, continental Europe, were crucial to his development. These journeys, often undertaken by coach, allowed for close observation of landscapes, architecture, and art. An early trip in 1833, during which he first encountered the Alps and the art of Italy, was particularly formative. It was also around this time, specifically at age 13, that a gift of Samuel Rogers's book Italy, illustrated with engravings after J.M.W. Turner, ignited his lifelong passion for the artist.

Ruskin attended Christ Church, Oxford, though his studies were interrupted by ill health, possibly tuberculosis, leading to further travels in Italy. Despite these interruptions, he won the prestigious Newdigate Prize for poetry in 1839. His formal education, combined with his extensive private study and travel, equipped him with a formidable breadth of knowledge. Inheriting a substantial fortune upon his father's death further enabled him to dedicate his life to writing, criticism, and social projects without the need for conventional employment.

The Champion of Turner: Modern Painters

Ruskin burst onto the literary scene with the publication of the first volume of Modern Painters in 1843. Initially conceived as a defense of the later, more experimental works of J.M.W. Turner against critical attacks, the project expanded over seventeen years into a sprawling five-volume treatise on the principles of art, nature, and society. Ruskin argued that Turner was the greatest landscape painter in history precisely because his work most truthfully captured the myriad aspects of the natural world – the structure of mountains, the forms of clouds, the movement of water, the growth of vegetation.

In Modern Painters, Ruskin challenged the conventions of academic art theory, which often prioritized idealized forms and historical subjects derived from classical and Renaissance models, particularly the landscapes of Claude Lorrain. Instead, Ruskin advocated for "truth to nature," urging artists to observe the world closely and render its specific details with accuracy and feeling. He believed that the beauty found in nature was a divine manifestation and that depicting it truthfully was a moral imperative for the artist.

The subsequent volumes of Modern Painters broadened in scope, exploring the works of other artists, delving into theories of beauty and the sublime, analyzing Renaissance art (particularly Venetian), and increasingly connecting artistic expression to the moral and social conditions of its time. While his initial focus was Turner, Ruskin's detailed analyses and passionate advocacy fundamentally shifted the discourse around landscape painting and the role of observation in art. He established himself as a dominant, if sometimes controversial, critical voice.

Engaging with the Pre-Raphaelites

Around 1851, Ruskin turned his critical attention towards a group of young, rebellious artists known as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB). Founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the PRB rejected the prevailing academic style, which they saw as formulaic and artificial, tracing its perceived decline back to the High Renaissance master Raphael. They sought inspiration in the art of the early Italian Renaissance (before Raphael), valuing bright colours, sharp detail, complex compositions, and serious, often morally charged subjects.

The PRB's early works met with harsh criticism for their perceived ugliness, archaism, and departure from established norms. Ruskin, seeing a parallel between their commitment to detailed naturalism and his own "truth to nature" principles, came to their defense in influential letters published in The Times. He praised their meticulous rendering of detail, their earnestness, and their rejection of artistic clichés, arguing that they represented a vital new direction in British art.

Ruskin developed personal relationships with several members of the group. He became a particular patron and supporter of Dante Gabriel Rossetti for a time, offering financial assistance and critical encouragement. His relationship with John Everett Millais became famously complicated. Ruskin's marriage to Euphemia "Effie" Gray was annulled in 1854 on grounds of non-consummation; Effie subsequently married Millais the following year, creating a permanent rift between the critic and the painter he had once championed. Despite this personal drama, Ruskin's support was crucial in establishing the PRB's reputation and influencing a generation of artists, including later figures associated with the movement like Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris. He also praised the detailed landscape work of artists like John Brett, though sometimes with reservations, while sharply criticizing others like Henry Wallis on occasion, despite acknowledging the power of specific works like Wallis's The Stonebreaker.

Architecture as a Moral Compass: The Seven Lamps and The Stones of Venice

Ruskin's interest in architecture was as profound as his engagement with painting. He saw buildings not merely as structures but as expressions of the society that created them, embodying its values, beliefs, and character. His two most significant works on the subject, The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) and The Stones of Venice (1851-1853), became hugely influential texts, particularly for the Gothic Revival movement.

The Seven Lamps of Architecture outlined seven guiding principles – Sacrifice, Truth, Power, Beauty, Life, Memory, and Obedience – which Ruskin believed were essential for meaningful architecture. He argued against deceit in construction (like disguised materials or structures) and advocated for honest craftsmanship, ornamentation derived from nature, and a sense of history and permanence. The book championed Gothic architecture, particularly its Northern European forms, for embodying these principles, contrasting it favourably with what he saw as the spiritually emptier styles derived from the Renaissance.

The Stones of Venice, a monumental three-volume work, offered an exhaustive historical and aesthetic analysis of the city's architecture, focusing on the relationship between its Gothic buildings and the purported moral and spiritual health of the medieval Venetian Republic. Ruskin contrasted the vitality and Christian piety he associated with the Gothic period with the decline he perceived during the Renaissance, which he linked to pride, sensuality, and a departure from truthful expression. The central volume, "The Nature of Gothic," became particularly famous, celebrating the creative freedom of the individual medieval craftsman in contrast to the dehumanizing, repetitive labour demanded by modern industry. This chapter profoundly influenced figures like William Morris and the burgeoning Arts and Crafts movement.

Expanding Horizons: Social and Economic Critique

By the late 1850s and early 1860s, Ruskin's focus began to shift decisively from art criticism towards a more direct engagement with social and economic issues. He became increasingly disturbed by the poverty, inequality, and environmental degradation accompanying Britain's industrialization. He saw the prevailing laissez-faire economic theories, which emphasized self-interest and competition, as fundamentally immoral and destructive to human well-being and the social fabric.

His most potent critiques of political economy appeared in essays first published in the Cornhill Magazine and later collected as Unto This Last (1862). This work fiercely attacked the foundations of classical economics, arguing for a system based on social justice, cooperation, and "intrinsic value" rather than mere market price. He advocated for fair wages, meaningful work, government intervention to protect the vulnerable, and a concept of "wealth" measured by well-being ("There is no wealth but life") rather than monetary accumulation. The book was met with outrage from the establishment press but proved deeply influential on later socialist thinkers, reformers, and figures like Mahatma Gandhi.

Ruskin continued to explore these themes in subsequent works like Munera Pulveris (1872) and his series of letters to the working men of Britain, Fors Clavigera (1871-1884). He condemned industrial pollution – famously describing the "Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century" – and lamented the loss of craftsmanship and beauty in mass production. His social vision, though sometimes paternalistic and idiosyncratic, consistently emphasized ethical responsibility, the dignity of labour, and the importance of beauty and nature for a healthy society.

The Guild of St George: A Utopian Experiment

Driven by his social conscience and a desire to put his ideas into practice, Ruskin founded the Guild of St George in the 1870s. This ambitious, if ultimately somewhat quixotic, organization aimed to create a practical alternative to the industrial capitalist society he deplored. The Guild acquired land, intending to establish agrarian communities based on cooperative principles, manual labour, traditional crafts, and reverence for nature. It also aimed to establish museums and educational initiatives for the working classes.

Ruskin poured much of his personal fortune into the Guild. While it never achieved the scale of his original vision, it did establish a small museum for workers in Sheffield (now the Ruskin Collection, Millennium Gallery, Sheffield) and undertook various agricultural and craft projects. The Guild represented Ruskin's attempt to translate his ideals of social justice, meaningful work, environmental stewardship, and aesthetic education into tangible action. It embodied his belief that a better society required not just critique but the active creation of alternative ways of living and working, rooted in ethical principles and a connection to the land. The Guild of St George continues to exist today, promoting Ruskin's ideas and supporting related educational and environmental projects.

Ruskin the Artist and Educator

Beyond his critical writings, Ruskin was himself a highly accomplished artist, particularly in watercolour and drawing. He possessed a remarkable eye for detail and a precise, delicate hand. His drawings and watercolours, often created during his travels, served multiple purposes: as personal records, as tools for close observation of natural and architectural forms, and as illustrations for his books. Works depicting Alpine scenery, Venetian architecture, or botanical details showcase his skill in capturing texture, structure, and light with scientific accuracy yet often imbued with poetic sensibility. Examples like The Matterhorn from the Moat of the Riffelhorn demonstrate this blend of precision and feeling.

Ruskin believed passionately in the educational value of drawing, not necessarily to train professional artists, but to teach people how to see the world more clearly and appreciate its beauty. He put these ideas into practice during his tenure as the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at the University of Oxford (1870-1879, and again 1883-1884). He established the Ruskin School of Drawing at Oxford and endowed it with a large collection of drawings, prints, and minerals for teaching purposes. His lectures were highly popular, though often unconventional, blending art history, technical instruction, and moral exhortation.

He also dedicated significant effort to educating working-class audiences, teaching drawing classes at the Working Men's College in London alongside figures like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Ford Madox Brown. For Ruskin, art education was intrinsically linked to moral and social development, a way to cultivate sensitivity, discipline, and an appreciation for the enduring values embodied in nature and great art.

Personal Trials and Later Years

Ruskin's public life as a celebrated critic and prophet was counterpointed by significant personal turmoil and, later, debilitating mental illness. His annulled marriage to Effie Gray in 1854 was a source of public scandal and personal pain. More profoundly affecting was his intense, unrequited, and ultimately tragic love for Rose La Touche, a young woman he met when she was a child. He proposed to her when she came of age, but she ultimately refused him, partly due to religious differences and concerns about his mental stability. Her early death in 1875 devastated Ruskin.

From the late 1870s onwards, Ruskin suffered recurring episodes of severe mental illness, likely a form of bipolar disorder, characterized by intense mania, delirium, and profound depression. These breakdowns increasingly interrupted his work and led to periods of withdrawal from public life. One famous incident reflecting his sometimes volatile critical judgment occurred in 1877 when he fiercely criticized a painting by James Abbott McNeill Whistler, accusing him of "flinging a pot of paint in the public's face." Whistler sued for libel, winning a symbolic victory but receiving only a farthing in damages. The trial highlighted the clash between Ruskin's emphasis on detailed representation and moral content and Whistler's advocacy of "art for art's sake."

Despite his declining health, Ruskin continued to write, producing his charming but fragmented autobiography, Praeterita ("Things Past"), between 1885 and 1889. He spent his final years in seclusion at his home, Brantwood, overlooking Coniston Water in the Lake District, cared for by his cousin Joan Severn. He died there on January 20, 1900. His later writings, including the often-apocalyptic Fors Clavigera and The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century, reflect both his enduring social concerns and, perhaps, the turbulence of his own mind. His harsh criticism of artists like Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, whom he reportedly called the "worst painter of the age," also belongs to this later, more polemical period.

Enduring Legacy and Influence

John Ruskin's influence during his lifetime was immense, shaping Victorian taste in art and architecture, inspiring social reformers, and challenging economic thought. Though his reputation waned in the early 20th century with the rise of Modernism, which often reacted against Victorian values, his work has experienced a significant revival since the 1960s. Scholars and the public have increasingly recognized the depth, prescience, and enduring relevance of his ideas.

His advocacy for truth to nature and detailed observation profoundly impacted the Pre-Raphaelites and landscape painting. His writings on architecture fueled the Gothic Revival and inspired the Arts and Crafts movement led by William Morris, who shared Ruskin's critique of industrial production and his belief in the value of craftsmanship. His emphasis on the social responsibility of the artist and the connection between art and morality continues to provoke debate.

Ruskin's social and economic critiques in works like Unto This Last influenced figures as diverse as Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, and early founders of the British Labour Party. His passionate arguments for environmental protection and his warnings against pollution are now seen as pioneering contributions to ecological thought. His advocacy for heritage preservation played a role in the founding of organizations like the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings and, indirectly, the National Trust. His ideas on education, particularly the importance of visual literacy and learning through observation, remain pertinent. Today, John Ruskin is recognized not just as a great Victorian writer and art critic, but as a visionary thinker whose holistic understanding of the relationship between art, nature, society, and ethics offers valuable insights for contemporary challenges.