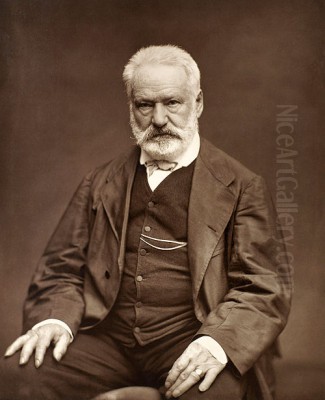

Victor Hugo (1802-1885) stands as a monumental figure in French culture and world literature. Primarily celebrated as the preeminent writer of the Romantic movement in France, his identity extended far beyond the literary realm. He was a poet, novelist, dramatist, influential politician, passionate human rights advocate, and, less famously but significantly, a prolific visual artist. Understanding Hugo requires acknowledging the interplay between these facets of his extraordinary life and career, a life that spanned tumultuous decades of French history and left an indelible mark on its artistic and political landscape.

Born in Besançon, France, Hugo's early life was shaped by the contrasting ideologies of his parents. His father, Joseph-Léopold-Sigisbert Hugo, was a high-ranking general in Napoleon Bonaparte's army, a man committed to the ideals of the Empire. His mother, Sophie Trébuchet, hailed from a staunchly Royalist and Catholic background. This parental divide mirrored the larger political schisms of post-Revolutionary France and instilled in the young Hugo a complex understanding of loyalty, power, and belief.

The family's life was peripatetic due to General Hugo's military postings. Victor spent parts of his childhood in Naples and Madrid, experiences that broadened his horizons and exposed him to different cultures and landscapes, elements that would later surface in his writings and drawings. The separation and eventual divorce of his parents further marked his youth, with Victor primarily raised by his mother in Paris, steeped in her Royalist sentiments during his formative years.

The Literary Titan

Hugo's literary talent manifested early. Encouraged by his mother, he began writing poetry as a teenager, quickly gaining recognition. By his early twenties, he was already a published poet and had founded a literary review, Le Conservateur littéraire, signaling his ambition and engagement with the cultural debates of the time. His early works, while showing technical skill, were largely aligned with the classical traditions and his mother's Royalist views.

However, Hugo soon became a driving force behind the burgeoning Romantic movement in France. This movement championed emotional expression, individualism, the beauty of nature, a fascination with the past (especially the medieval period), and a focus on the sublime and the grotesque over the Neoclassical ideals of order and reason. Hugo's play Cromwell (1827), though too long to be staged, featured a preface that became a manifesto for French Romanticism, advocating for the rejection of rigid classical rules, particularly the unities of time and place in drama.

The premiere of his play Hernani in 1830 was a watershed moment, famously sparking riots between conservative Classicists and enthusiastic Romantics. The "Battle of Hernani," as it became known, symbolized the triumph of the new Romantic aesthetic in French theatre. Hugo's victory cemented his position as a leader of the movement, alongside figures like the painter Eugène Delacroix, whose own dramatic and colourful style resonated with Romantic ideals.

Hugo's literary output was prodigious and varied. His poetry collections, such as Les Orientales (1829), Les Feuilles d'automne (1831), and Les Contemplations (1856), showcased his lyrical genius, his mastery of rhythm and imagery, and his evolving philosophical and personal reflections. He explored themes of love, nature, grief, spirituality, and social commentary with unparalleled eloquence.

His novels remain his most internationally renowned works. Notre-Dame de Paris (1831), often translated as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, is a vivid historical novel set in medieval Paris. It brought the neglected Gothic cathedral back into public consciousness, contributing significantly to its preservation. The novel masterfully blends historical detail with dramatic storytelling, featuring unforgettable characters like Quasimodo, Esmeralda, and Claude Frollo, and exploring themes of fate, social injustice, and the power of architecture as a historical record.

Decades later, while in exile, Hugo produced his magnum opus, Les Misérables (1862). This sprawling epic novel follows the intertwined lives of several characters over decades, set against the backdrop of social unrest and political upheaval in 19th-century France, including the 1832 June Rebellion in Paris. Centered on the story of ex-convict Jean Valjean and his quest for redemption, the novel is a powerful indictment of social inequality, poverty, and the failures of the justice system, while simultaneously celebrating compassion, sacrifice, and the endurance of the human spirit. It remains one of the most widely read and adapted novels in history.

Other significant novels include Les Travailleurs de la mer (Toilers of the Sea, 1866), a story of man's struggle against the forces of nature, and L'Homme qui rit (The Man Who Laughs, 1869), a dark tale exploring aristocracy, identity, and social cruelty. Throughout his literary career, Hugo consistently used his platform to champion the marginalized and critique societal flaws.

Political Engagement and Exile

Hugo's life was deeply intertwined with the political transformations of France. Initially influenced by his mother's Royalism, he accepted pensions from King Louis XVIII and Charles X. However, his views evolved significantly over time. Witnessing the social injustices and political instability of the era, particularly the July Revolution of 1830 and the rise of Louis-Philippe, pushed him towards more liberal and eventually republican ideals.

In 1841, he was elected to the Académie Française, a mark of high literary distinction. In 1845, King Louis-Philippe elevated him to the peerage, granting him a seat in the upper house of parliament. Hugo used this position to speak out on issues like poverty, the death penalty (which he vehemently opposed throughout his life), and freedom of the press. He advocated for social reform and universal suffrage.

The Revolution of 1848, which established the Second Republic, saw Hugo initially support Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (Napoleon III) as president. However, when Louis-Napoléon staged a coup d'état in December 1851, dissolving the National Assembly and declaring himself Emperor, Hugo became one of his fiercest opponents. Declaring the Emperor a traitor to the Republic, Hugo was forced into exile to avoid arrest.

This exile would last nearly two decades (1851-1870). He first fled to Brussels, then moved to the British Channel Islands, living on Jersey and later Guernsey. This period of enforced separation from France was personally difficult but creatively fertile. It was during his exile on Guernsey, at his home Hauteville House, that he completed Les Misérables and produced a significant body of visual art.

From exile, Hugo continued his political attacks against Napoleon III, publishing scathing works like Napoléon le Petit (Napoleon the Little, 1852) and Histoire d'un crime (History of a Crime, written 1851-52, published 1877), which documented the coup. He became a symbol of republican resistance, refusing offers of amnesty, stating he would only return when liberty was restored to France.

He finally returned in triumph after Napoleon III's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and the proclamation of the Third Republic in September 1870. He was greeted as a national hero. He was elected to the National Assembly and later became a Senator for life, continuing to advocate for his long-held beliefs in democracy, social justice, and human rights until his death.

The Hidden Artist: Hugo the Painter

While Hugo's literary fame overshadowed his other talents during his lifetime, he was also a remarkably gifted and prolific visual artist. He produced over 4,000 drawings and paintings, primarily for his private enjoyment or as gifts for friends and family, never considering it his main profession. Approximately 3,000 of these works survive today, housed mainly in the Maison de Victor Hugo in Paris and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Hugo's artistic practice began in his youth with sketches and caricatures, but it intensified significantly during his exile. Cut off from the Parisian literary scene and the political stage, drawing became a vital creative outlet, a way to process his experiences, express his emotions, and explore the landscapes and imaginative realms that occupied his mind. His art was deeply personal, often created spontaneously and with unconventional methods.

Techniques and Materials

Hugo approached drawing with the same experimental spirit he brought to writing. He was largely self-taught and felt unconstrained by academic conventions. His preferred medium was typically pen and ink wash, often using brown or black ink, sometimes augmented with charcoal, watercolour, gouache, or even soot and coffee grounds. He was a master of lavis (ink wash), creating dramatic contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) reminiscent of artists like Rembrandt van Rijn and Giovanni Battista Piranesi, whose atmospheric etchings of ruins Hugo admired.

He employed innovative and often playful techniques. He would sometimes draw with his non-dominant hand or in the dark to tap into subconscious creativity. He experimented with inkblots (taches), folding the paper over wet ink to create symmetrical or suggestive shapes, which he would then elaborate upon. He used stencils, lace imprints, finger painting, and scratching or rubbing the paper to achieve different textures. This willingness to experiment with materials and processes foreshadowed techniques later explored by Surrealist artists like Max Ernst.

Themes and Subjects

Hugo's visual art echoes many of the themes found in his writing. Landscapes dominate his oeuvre, particularly the dramatic coastal scenery of the Channel Islands where he spent his exile. He depicted turbulent seas, jagged cliffs, lighthouses battered by storms (like his famous drawings of the Casquets lighthouse), and atmospheric views of the Rhine River valley, which he had visited earlier. These landscapes are rarely tranquil; they often convey a sense of Romantic sublimity, emphasizing the power and mystery of nature, sometimes dwarfing human presence.

Architecture, especially medieval castles, ruins, and imagined Gothic structures, was another favourite subject. These drawings often possess a haunting, dreamlike quality, evoking a sense of history, decay, and fantasy. His famous novel Notre-Dame de Paris reveals his deep fascination with Gothic architecture, a passion clearly visible in his drawings as well.

He also created fantastical and grotesque figures, spectral apparitions, and symbolic compositions dealing with themes of fate, death, justice, and struggle. Some drawings served as illustrations or conceptual sketches for his literary works, such as the powerful images he created for Les Travailleurs de la mer. Furthermore, his interest in spiritualism, particularly during his time on Jersey, sometimes manifested in strange, abstract, or automatic drawings.

Artistic Style and Evolution

Hugo's style is characterized by its dramatic intensity, bold contrasts, and expressive freedom. While rooted in the Romantic sensibility, his work often pushes beyond it. His use of dark tones, stark lighting, and sometimes distorted forms creates a powerful emotional impact, aligning him with the darker Romanticism of artists like Francisco Goya. His fluid ink washes and atmospheric effects show an affinity with the work of the British master J.M.W. Turner, whose paintings Hugo likely saw during visits to London.

Critically, Hugo's visual art anticipates several later art movements. His experimental techniques, his interest in chance and the subconscious, and his creation of abstract patterns from ink stains connect him to Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism. His focus on subjective experience and symbolic imagery also links him to the Symbolist movement that emerged later in the 19th century, influencing artists like Odilon Redon. Though he worked in relative isolation as an artist, his visual output is now recognized as remarkably prescient and innovative.

Hugo and His Contemporaries in the Art World

Although Hugo did not actively participate in the Parisian art scene as a painter, his work was known and admired by some key figures. The leading French Romantic painter, Eugène Delacroix, was a contemporary and acquaintance. It is reported that Delacroix, upon seeing Hugo's drawings, remarked that if Hugo had chosen to dedicate himself to painting instead of literature, he would have outshone all the artists of their century. This comment highlights the perceived power and originality of Hugo's visual work, even from a giant of the era.

Hugo was also friends with other artists, such as the illustrator and painter Achille Devéria, who created portraits of Hugo and his circle. The influential poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire, a complex figure in Hugo's life (sometimes admiring, sometimes critical), discussed Hugo's literary and, implicitly, his artistic stature, often comparing him to Delacroix, suggesting their parallel importance within the Romantic movement.

While Hugo's direct interaction with many painters might have been limited, his work resonates with the broader artistic currents of his time and beyond. His dramatic use of light and shadow connects him to Rembrandt and Piranesi. His turbulent landscapes find echoes in Turner and, to some extent, the work of French landscape painters like Georges Michel or even later, Gustave Courbet's powerful seascapes. His interest in social commentary through visual means aligns him with Honoré Daumier, the great caricaturist and painter of modern life.

Later artists also recognized his significance. Vincent van Gogh expressed admiration for Hugo's drawings. The Symbolists found inspiration in his imaginative and often dark visions. The Surrealists, particularly Max Ernst, explicitly acknowledged Hugo's experimental techniques with ink stains (taches) as a precursor to their own explorations of automatism and chance in art creation. Hugo's visual art, therefore, exists in a dialogue with artists ranging from Old Masters like Rembrandt to pioneers of modern art. His contemporaries included not only Romantics like Delacroix and Théodore Géricault but also Neoclassicists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Realists like Courbet and Jean-François Millet, and Barbizon School painters like Camille Corot.

Personal Life: Passion and Controversy

Hugo's personal life was as dramatic and complex as his literary creations. In 1822, he married his childhood sweetheart, Adèle Foucher. The marriage produced five children, but was marked by tragedy, including the early death of his eldest son and the drowning of his beloved daughter Léopoldine in 1843, an event that devastated Hugo and profoundly influenced his later work, particularly Les Contemplations.

His marriage to Adèle was also complicated by infidelity on both sides. Hugo himself began a lifelong liaison with the actress Juliette Drouet in 1833. Drouet became his devoted companion and secretary for nearly fifty years, enduring his other affairs and remaining fiercely loyal until her death in 1883. This relationship, though unconventional and a source of social commentary, was a central pillar of Hugo's emotional life. His letters to her provide invaluable insight into his daily life, thoughts, and creative process.

Hugo's immense fame and strong personality made him a figure of public fascination. His passionate nature, his political battles, his exile, and his complex family life all contributed to his larger-than-life persona. He was a man of enormous appetites – for work, for love, for justice – and his life, like his art, was lived on an epic scale.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Victor Hugo died in Paris on May 22, 1885, at the age of 83. His death prompted a national outpouring of grief unprecedented for a literary figure. He was given a state funeral, attended by an estimated two million people, the largest public mourning France had ever witnessed. His body lay in state under the Arc de Triomphe before being interred in the Panthéon, the final resting place reserved for France's greatest citizens, alongside figures like Voltaire and Rousseau.

Hugo's legacy is immense and multifaceted. As a writer, he remains one of the giants of French literature, credited with shaping the Romantic movement and producing works that continue to resonate globally. Les Misérables and Notre-Dame de Paris are perpetually rediscovered through adaptations in theatre, film, and television, introducing his stories and themes to new generations. His poetry is still studied and admired for its technical brilliance and emotional depth.

His political legacy is equally significant. He became an enduring symbol of republicanism, democracy, and social justice in France. His unwavering opposition to the death penalty, his advocacy for the poor and marginalized, and his passionate defense of liberty cemented his status as a moral authority and a national conscience. His famous quote, "Nothing is more powerful than an idea whose time has come," reflects his belief in progress and social change.

In the realm of visual arts, Hugo's reputation has grown steadily since his death. Initially dismissed by some as the mere hobby of a writer, his drawings are now recognized for their intrinsic artistic merit, their technical innovation, and their historical importance as precursors to later art movements. Exhibitions of his artwork attract significant attention, revealing a darker, more intimate, and visually experimental side to the celebrated author. He demonstrated that artistic genius could transcend mediums.

Conclusion: A Universe Within One Man

Victor Hugo was more than a writer; he was a force of nature, a universe contained within one man. His life spanned monarchy, revolution, empire, and republic, and he engaged with the turbulent currents of his time with unparalleled energy and passion. His literary works explored the heights of human aspiration and the depths of suffering, championing love, justice, and redemption while fiercely condemning tyranny and inequality.

His political activism gave voice to the voiceless and shaped the course of French republicanism. And his often-overlooked visual art provides a fascinating window into his inner world, revealing a restless, experimental spirit that pushed the boundaries of artistic expression. Across all his endeavors, Hugo displayed a profound empathy for humanity, a powerful imagination, and an unwavering commitment to his ideals. He remains a towering figure not just in French history, but in the broader story of human creativity and the struggle for a more just world. His words and images continue to inspire, provoke, and console, securing his place as one of the most influential and enduring artists of all time.