Elihu Vedder stands as a unique and compelling figure in the landscape of nineteenth and early twentieth-century American art. Born in New York City on February 26, 1836, Vedder forged a path distinct from many of his contemporaries, embracing symbolism, mysticism, and a deeply personal iconography that set his work apart. He was not merely a painter but also a gifted illustrator, a poet, and a designer whose creative output spanned decades and continents, leaving an indelible mark on the Gilded Age and beyond. His life, marked by transatlantic journeys, financial struggles, profound artistic exploration, and enduring connections within the international art world, offers a fascinating glimpse into a mind captivated by the enigmatic and the sublime.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Elihu Vedder's journey into art began in a household where creative pursuits were met with mixed reactions. His father, Dr. Elihu Vedder Sr., a dentist whose profession took the family between New York and Cuba, initially harbored reservations about his son pursuing the uncertain life of an artist. However, his mother, Elizabeth Vedder, proved a crucial source of encouragement, nurturing his burgeoning talent. This early dynamic perhaps foreshadowed the independence and determination that would characterize Vedder's career.

His formal artistic training commenced in New York City under the tutelage of Tompkins H. Matteson, a genre painter in Sherburne, New York. Seeking more rigorous instruction, Vedder, like many aspiring American artists of his generation, looked towards Europe. He traveled to Paris in 1856, immersing himself in the academic environment of the atelier system. There, he studied with François-Édouard Picot, a painter known for his historical and mythological subjects, absorbing the fundamentals of classical draftsmanship and composition.

However, it was Italy that would truly capture Vedder's imagination and shape his artistic destiny. Arriving in Florence around 1857, he stepped into a world steeped in the legacy of the Renaissance masters. The art of Michelangelo, Raphael, and their contemporaries left a profound impression, but Vedder was equally drawn to the more contemporary currents stirring within the Italian art scene.

Florentine Years and the Macchiaioli

During his formative years in Florence (roughly 1857-1860), Vedder found himself amidst a vibrant artistic milieu. He frequented the Caffè Michelangelo, a legendary gathering spot for a group of revolutionary young painters who would become known as the Macchiaioli. These artists, including figures like Giovanni Fattori, Silvestro Lega, and Telemaco Signorini, were reacting against the staid conventions of academic art, advocating for painting outdoors (en plein air) and using bold patches (macchie) of color and light to capture immediate impressions of reality.

Vedder developed a particularly close friendship with Giovanni Costa, a leading figure associated with the Macchiaioli and a landscape painter of great sensitivity. Together, they explored the Tuscan countryside, sketching and painting directly from nature. This experience instilled in Vedder a deep appreciation for landscape and light, though his own path would diverge significantly from the naturalism of his Italian friends. The influence remained, however, visible in the atmospheric quality and evocative landscapes that often form the backdrops for his more imaginative works. His time in Florence exposed him to both the weight of history and the pulse of modern artistic experimentation.

This initial Italian sojourn was not without its hardships. Vedder's father, perhaps still skeptical of his son's chosen path, significantly reduced his financial support. This forced interruption brought Vedder back to the United States in 1860, just as the nation stood on the brink of civil war. The return marked the end of a crucial developmental phase but also set the stage for a new chapter in his artistic evolution.

Civil War Interlude and Early Masterpieces

Returning to America during the tumultuous Civil War years presented Vedder with significant challenges. The art market was unstable, and patronage was scarce. To make ends meet, he turned his hand to commercial illustration, creating drawings for publications like Vanity Fair and Harper's Weekly. He also undertook decorative work and even designed Christmas cards, demonstrating a practical versatility born of necessity. This period, though difficult financially, was creatively fertile.

Living in New York, Vedder became associated with the bohemian circle that gathered at Pfaff's beer cellar, a hub for writers, artists, and intellectuals. Here, he likely encountered figures such as Walt Whitman, whose expansive poetic vision may have resonated with Vedder's own imaginative tendencies. He also formed connections with artists like William Morris Hunt, a painter who had studied in Europe and brought back cosmopolitan influences. These interactions broadened his horizons and likely fueled his artistic ambitions beyond mere commercial work.

It was during this period that Vedder produced some of his most haunting and iconic early paintings, works that announced his arrival as a unique voice in American art. The Lair of the Sea Serpent (1864), depicting a monstrous creature coiled languidly on a desolate shore under an ominous sky, showcases his fascination with the bizarre and the powerful forces of nature. The painting's unsettling atmosphere and imaginative subject matter were unlike anything being produced by his American contemporaries.

Equally significant was The Questioner of the Sphinx (1863). This enigmatic work portrays a figure kneeling in the desert sand, pressing his ear against the lips of the ancient monument, seeking answers to profound existential questions. The painting combines meticulous realism in the rendering of the figures and landscape with a deeply symbolic and mysterious theme. It reflects Vedder's burgeoning interest in ancient myths, esoteric knowledge, and the timeless human search for meaning, themes that would recur throughout his career. These works, born from a period of personal struggle and national turmoil, established Vedder's reputation for imaginative power and technical skill, even if their unconventional nature sometimes met with puzzlement or controversy.

The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: A Landmark Achievement

Vedder's most widely celebrated achievement came not through a single painting, but through a series of illustrations that became intrinsically linked with a beloved work of literature. In 1884, the publishing house Houghton Mifflin released an edition of Edward FitzGerald's translation of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, featuring fifty-five masterful illustrations by Elihu Vedder. This project was a perfect marriage of text and image, catapulting both the poem and the artist to new heights of fame.

FitzGerald's evocative verses, with their meditations on fate, mortality, pleasure, and the passage of time, provided fertile ground for Vedder's symbolic imagination. He approached the commission not merely as illustration but as a parallel visual interpretation, creating powerful, self-contained compositions that resonated with the poem's philosophical depth and sensual imagery. Vedder designed the entire book, including the cover, lettering, and decorative motifs, resulting in a unified work of art that became a touchstone of the Aesthetic Movement in America.

The illustrations themselves are remarkable for their blend of Western academic drawing and perceived "Oriental" motifs, though filtered through Vedder's unique lens. Figures often possess a sculptural solidity, reminiscent of Renaissance art, yet they inhabit dreamlike landscapes filled with swirling nebulae, symbolic objects, and mystical presences. Works like The Pleiades, The Cup of Death, and The Recording Angel became iconic images, widely reproduced and admired. The Rubáiyát illustrations showcased Vedder's mastery of line, his inventive compositions, and his ability to translate complex philosophical ideas into compelling visual form.

The publication was an immediate and resounding success, both critically and commercially. It cemented Vedder's reputation as a leading figure in American art and arguably the foremost exponent of Symbolism in the country at that time. The book went through numerous printings and remains a landmark in the history of American illustration and book design. For Vedder, it brought not only fame but also a measure of financial security, allowing him greater freedom in his subsequent artistic endeavors.

Mature Style: Symbolism, Mysticism, and Decoration

Following the triumph of the Rubáiyát, Vedder's artistic path was firmly established. While he continued to paint landscapes and occasional portraits, his primary focus remained on imaginative subjects imbued with symbolic meaning. His style drew from a diverse range of influences – the precision of the Renaissance, the atmospheric effects explored by the Macchiaioli, the linearity of Pre-Raphaelite artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, and the visionary intensity of William Blake. Yet, Vedder synthesized these elements into a highly personal visual language.

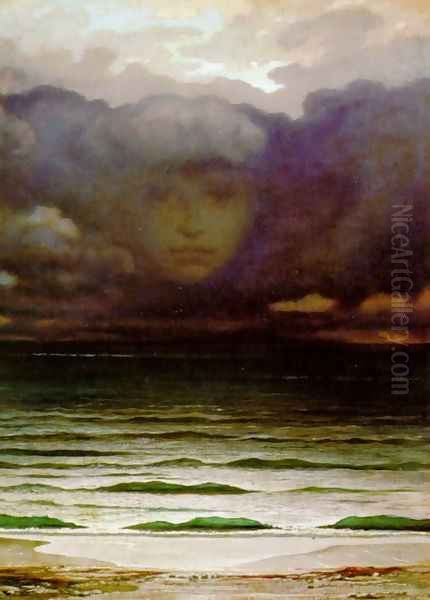

His works often explore themes of fate, destiny, life, death, and the mysteries of the universe. Figures are frequently depicted in states of contemplation, struggle, or enigmatic repose, set against vast, evocative landscapes or cosmic backdrops. Paintings like Memory (1870), depicting a brooding figure seated by a reflective pool containing fragmented memories, or The Fisherman and the Mermaid (1888-89), exploring themes of temptation and the allure of the unknown, exemplify his mature style. Young Marsyas (1878), showing the satyr charming animals with his flute before his fatal contest with Apollo, delves into classical mythology with a characteristic blend of realism and fantasy.

Vedder's approach was deeply influenced by dreams, visions, and the subconscious, predating the Surrealist movement by several decades. He sought to give form to abstract ideas and emotional states, using recurring symbols like spheres, serpents, wings, and desolate landscapes to convey complex meanings. His compositions often feature strong outlines, flattened planes of color, and a decorative sensibility, reflecting the influence of the Aesthetic Movement, which emphasized "art for art's sake" and the integration of art into everyday life through design.

This decorative impulse found expression not only in his book illustrations but also in designs for murals, mosaics, stained glass, and even furniture. Vedder believed in the power of art to enrich environments and elevate the human spirit, moving beyond the confines of the easel painting.

Roman Years and Monumental Commissions

Although Vedder traveled extensively and maintained ties to the United States, Italy, particularly Rome, became his spiritual and physical home for much of his adult life. He settled there permanently in 1867 and remained based in Italy until his death. The Eternal City, with its layers of history, classical ruins, and vibrant expatriate community, provided endless inspiration. He became a prominent figure among the international artists living in Rome, known for his wit, intellect, and distinctive artistic vision.

In Rome, Vedder continued to associate with artists and intellectuals. He was instrumental in the formation of the In Arte Libertas group around 1886 (though some sources cite 1890), an association of artists, including his old friend Giovanni Costa, who sought to promote artistic freedom and individuality against the constraints of academicism. This involvement underscores Vedder's lifelong commitment to pursuing his own artistic path, regardless of prevailing trends.

His reputation, bolstered by the Rubáiyát's success, led to significant public commissions back in the United States. The most notable of these were the murals and mosaics he designed for the Collis P. Huntington mansion in New York (sadly, now demolished) and, more enduringly, for the Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building in Washington, D.C. Between 1896 and 1897, Vedder created a series of five lunette murals and a mosaic depicting Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom, for the entrance hall leading to the Main Reading Room.

The murals, representing themes of Government, Anarchy, Peace and Prosperity, Corrupt Legislation, and Good Administration, are powerful allegorical works executed in Vedder's characteristic style. They combine classically inspired figures, strong compositions, and rich symbolism to convey complex ideas about civic virtue and societal order. The Minerva mosaic, a shimmering centerpiece, further demonstrates his skill in decorative design and his ability to work on a monumental scale. These commissions represent a significant contribution to the American Renaissance, a period marked by a desire to adorn public spaces with art that reflected national ideals and aspirations, often looking to European precedents like the works of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes in France.

Artistic Circle and Connections

Throughout his long career, Elihu Vedder moved within a diverse and influential circle of artists, writers, and patrons on both sides of the Atlantic. His early friendships in Florence with Giovanni Costa and the Macchiaioli were formative. His time at Pfaff's in New York connected him with the city's bohemian scene, including Walt Whitman and potentially Herman Melville, whose own explorations of profound themes might have found resonance with Vedder. His friendship with William Morris Hunt linked him to the Boston art world and broader cosmopolitan currents.

As an established figure, particularly after the Rubáiyát, Vedder's path crossed with many leading artists of the Gilded Age. While living as an expatriate in Rome and Capri, he would have known or encountered fellow American artists like John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler, though his style remained distinct from their more impressionistic or tonalist approaches. His work, with its emphasis on imagination and symbolism, aligns more closely with European Symbolists like Gustave Moreau or Odilon Redon in France, or Arnold Böcklin in Switzerland, though Vedder forged his own independent version of symbolic art.

His interest in mysticism and visionary art connected him intellectually to figures like William Blake and the later W.B. Yeats, whose explorations of mythology and the esoteric paralleled Vedder's own preoccupations. While direct collaboration was rare outside of his illustration work, his engagement with these varied artistic and literary figures enriched his perspective and situated him within the broader cultural dialogues of his time. He was respected for his unique vision, even by those whose artistic aims differed significantly.

Personal Life, Beliefs, and "The Digressions of V."

Vedder's personal life was centered around his family and his adopted home in Italy. In 1869, he married Caroline Rosekrans, and together they had four children. Tragically, two died young, a common sorrow in that era. His surviving daughter, Anita Herriman Vedder, became an important figure in his later life, assisting him with his business affairs and helping to manage his legacy. His son, Enoch Rosekrans Vedder, pursued a career as an architect but sadly predeceased his father in 1916. These personal losses undoubtedly colored Vedder's worldview and perhaps deepened the melancholic and philosophical strains in his art.

Vedder documented his life, thoughts, and encounters in his autobiography, The Digressions of V., published in 1910. Written in a charmingly rambling and anecdotal style, the book offers invaluable insights into his personality, his artistic journey, and the times in which he lived. It recounts his childhood adventures, his student days in Europe, his struggles and successes, and his encounters with fellow artists and notable figures.

The Digressions also reveal glimpses of Vedder's complex spiritual and philosophical beliefs. While raised in a broadly Christian culture, he expressed skepticism towards organized religion and conventional dogma. He wrote of his disbelief in a "complete family in Heaven" and found the concept of judgment "nebulous." His art often grapples with profound questions about existence, fate, and the nature of reality, suggesting a mind deeply engaged with spiritual matters but unwilling to accept easy answers. This intellectual independence and questioning spirit are central to understanding both the man and his art.

Later Years, Legacy, and Market Presence

Elihu Vedder spent his final decades primarily in Italy, dividing his time between his home in Rome and his beloved Villa dei Quattro Venti on the island of Capri. He continued to paint and draw, though perhaps with less intensity than in his prime. He remained a respected figure, a living link to an earlier era of art, sought out by younger artists and visitors to Italy. His distinctive appearance, often sporting a skullcap and flowing beard, made him a recognizable character in the expatriate community.

He died in Rome on January 29, 1923, just shy of his 87th birthday, and was buried in the city's Protestant Cemetery, not far from the graves of the English poets Keats and Shelley. His death marked the passing of one of the last major figures associated with nineteenth-century American Symbolism.

Vedder's legacy is preserved through his extensive body of work, held in major museums across the United States and beyond, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Brooklyn Museum. His papers, including letters, diaries, and sketches, were donated to the Archives of American Art, providing rich resources for scholars. His daughter Anita also ensured significant donations of his work to institutions like the Library of Congress and Boston College.

In the art market, Vedder's works appear periodically at auction. Paintings like Off the Pier Head, Viareggio, Italy (1881) have commanded respectable prices, reflecting his established place in American art history. However, detailed public auction records for some of his most famous works, such as The Questioner of the Sphinx or The Fisherman and the Mermaid, are scarce, as these often reside in museum collections or long-held private hands. His drawings and studies, particularly those related to the Rubáiyát, are also sought after by collectors. While perhaps not reaching the stratospheric prices of some Impressionist or Modernist masters, Vedder's work retains significant value, appreciated for its unique style, imaginative power, and historical importance.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

Elihu Vedder occupies a unique niche in the history of art. An American by birth, he was profoundly shaped by Europe, particularly Italy, yet his artistic voice remained distinctly his own. He navigated the currents of Academicism, the Macchiaioli, the Aesthetic Movement, and Symbolism, borrowing elements from each but adhering strictly to none. His work delves into the realms of myth, dream, and the subconscious, exploring timeless questions of human existence with a blend of technical mastery and visionary intensity.

From the haunting enigma of The Questioner of the Sphinx to the lush, philosophical world of the Rubáiyát illustrations and the monumental allegories of the Library of Congress, Vedder consistently pursued a highly personal iconography. He was a bridge between the meticulous realism of the nineteenth century and the burgeoning interest in symbolism and the inner world that would characterize much of modern art. Though sometimes seen as an outlier or an eccentric, Elihu Vedder's enduring body of work stands as a testament to a singular artistic vision, one that continues to fascinate and resonate with its blend of beauty, mystery, and profound contemplation.