Robert Van Vorst Sewell (1860-1924) stands as an intriguing figure in American art history, an artist whose career spanned the dynamic period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A product of both American ambition and European academic training, Sewell became particularly known for his murals and his engagement with literary and mythological themes. While perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his Gilded Age contemporaries, his work offers a valuable lens through which to view the artistic currents of his time, from the enduring legacy of academic painting to the burgeoning American Renaissance.

Early Life and Formative Parisian Training

Born in New York City in 1860, Robert Van Vorst Sewell emerged into a nation still healing from the Civil War and on the cusp of unprecedented industrial and cultural growth. Like many aspiring American artists of his generation, Sewell recognized that the path to artistic mastery and recognition often led across the Atlantic to the established art centers of Europe, particularly Paris. The French capital was the undisputed epicenter of the art world, home to prestigious academies, influential Salons, and a vibrant community of artists from around the globe.

Sewell made his way to Paris and enrolled in the Académie Julian. This private art school, founded by Rodolphe Julian in 1868, was a crucial alternative and supplement to the more rigid, state-run École des Beaux-Arts. The Académie Julian was particularly popular with foreign students, including many Americans, as it offered a more flexible curriculum and access to instruction from renowned academic painters who also taught at or were associated with the École.

At the Académie Julian, Sewell studied under two prominent figures of French academic art: Jules Joseph Lefebvre (1836-1911) and Gustave Clarence Rodolphe Boulanger (1824-1888). Lefebvre was celebrated for his masterfully rendered female nudes and portraits, a quintessential academic artist who emphasized precise drawing, smooth finish, and idealized forms. Boulanger, similarly, was a respected figure known for his historical and Orientalist paintings, also adhering to the academic traditions of meticulous detail and classical composition. The tutelage of such masters would have instilled in Sewell a strong foundation in draughtsmanship, anatomy, and the classical principles of art that were the bedrock of academic training. This education emphasized a rigorous approach to figure painting, a skill that would serve him well, particularly in his later mural work.

The Influence of the Académie Julian and Its Milieu

The Académie Julian was more than just a place of instruction; it was a crucible where artistic ideas were exchanged and careers were forged. Sewell would have been surrounded by a diverse group of international students, all striving for recognition. The environment was competitive yet collaborative. Artists like Thomas Dewing, Childe Hassam, John Singer Sargent (though primarily trained under Carolus-Duran), and Frederick MacMonnies were among the many Americans who passed through Parisian ateliers, including the Académie Julian, during this period.

The training received under Lefebvre and Boulanger would have exposed Sewell to the prevailing tastes of the official Salons, the annual state-sponsored exhibitions that could make or break an artist's career. Success at the Salon often meant adherence to academic conventions, though the late 19th century also saw the rise of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, which challenged these very conventions. While Sewell's later work shows an inclination towards romantic and literary themes rather than Impressionistic light studies, the academic discipline acquired in Paris remained a constant.

Return to America and the Rise of a Muralist

Upon returning to the United States, Sewell established himself as a professional artist. He initially settled in Oyster Bay, Long Island, a fashionable enclave that attracted many affluent New Yorkers. This period, often referred to as the Gilded Age, was characterized by immense wealth, industrial expansion, and a desire among the American elite to emulate European cultural sophistication. This cultural ambition fueled a demand for art, particularly for grand public and private commissions.

Sewell became particularly noted as a muralist. The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed a significant revival of mural painting in America, often termed the "American Renaissance." This movement saw architects, sculptors, and painters collaborating on ambitious decorative schemes for public buildings (libraries, capitols, courthouses) and the opulent mansions of the newly wealthy. Artists like John La Farge, Edwin Howland Blashfield, Kenyon Cox, and Elihu Vedder were leading figures in this mural movement, creating allegorical, historical, and mythological scenes that aimed to elevate public taste and express national ideals.

Sewell's skill in figure composition and his academic training made him well-suited for mural work, which often required large-scale, complex narrative scenes. His involvement in this field placed him squarely within a significant artistic trend of his era. He traveled extensively and participated in numerous art exhibitions, including the prestigious Paris Salon, the Boston Art Club, and the National Academy of Design in New York, showcasing his versatility.

Masterpiece in Mural Form: "The Canterbury Pilgrims"

One of Robert Van Vorst Sewell's most significant and representative works is the mural The Canterbury Pilgrims, completed in 1897. This ambitious work was commissioned for the George Jay Gould I estate, "Lakewood," in Lakewood, New Jersey. Gould, a prominent financier and railroad executive, was the son of the infamous Jay Gould, and his estate was a testament to the lavish lifestyles of America's Gilded Age magnates.

The subject matter, drawn from Geoffrey Chaucer's 14th-century Middle English classic, The Canterbury Tales, was a popular one, evoking a sense of history, literature, and pageantry. Chaucer's work describes a diverse group of pilgrims traveling to the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket in Canterbury, each telling stories along the way. Sewell's mural would have depicted this colorful procession, allowing for a rich tapestry of characters and costumes, a hallmark of historical and literary genre painting.

The choice of such a theme reflects the era's appetite for art that was both decorative and edifying, connecting the New World's burgeoning culture with the established literary traditions of Europe. For an estate like Lakewood, such a mural would have added an air of baronial splendor and intellectual refinement. The execution of The Canterbury Pilgrims would have demanded considerable skill in composition, character portrayal, and historical detail, showcasing Sewell's academic training to full effect. It remains one of the most notable artistic features of the historic estate.

Exploring Myth and Legend: "The Birth of Ogier the Dane"

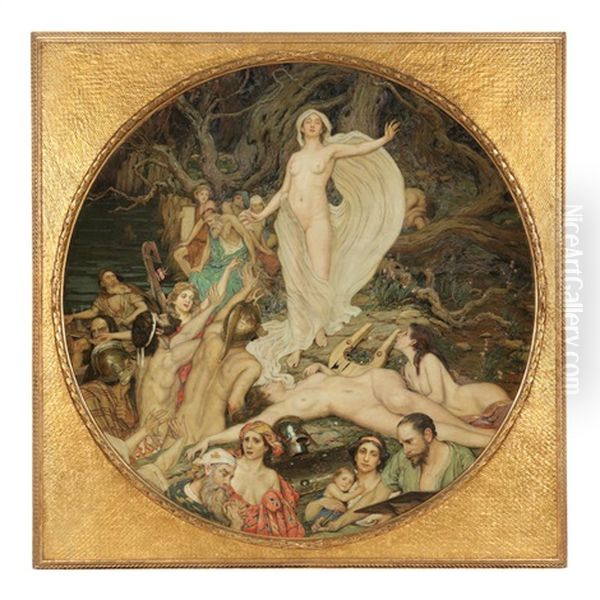

Beyond large-scale murals, Sewell also created easel paintings, often exploring mythological and literary themes that resonated with late Romantic and Symbolist sensibilities. A key example is The Birth of Ogier the Dane, a painting first exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York in 1904. It was subsequently shown in St. Louis (likely at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904) and again in New York in 1909.

The subject, Ogier the Dane, is a legendary Danish hero from medieval romances and chansons de geste. The painting depicts the infant Ogier being endowed with gifts by six fairies or enchantresses, a scene inspired by literary sources, possibly including those by Virginia Morris (a likely reference to a contemporary writer or a figure from the Arts and Crafts movement, perhaps even connected to William Morris, though this specific connection needs careful verification). This theme of magical endowment and heroic destiny aligns with the period's fascination with folklore, chivalry, and the mystical.

Artistically, The Birth of Ogier the Dane is described as showcasing a romantic style. The composition, featuring ethereal figures and a narrative steeped in legend, would have appealed to an audience familiar with Pre-Raphaelite art (e.g., works by Dante Gabriel Rossetti or Edward Burne-Jones) or the Symbolist paintings of European artists like Gustave Moreau or Puvis de Chavannes, which often delved into myth, dream, and allegory. While the provided information suggests this painting did not achieve widespread critical acclaim at the time, it remains significant as a documented work that reveals Sewell's thematic preoccupations and stylistic leanings. It is noted as his only known painting with this specific subject, highlighting a particular foray into this legendary narrative.

Other Notable Works and Thematic Interests

Sewell's oeuvre included other works that further illustrate his engagement with romantic and mythological subjects. Paintings such as Psyche Seeks Love and A Seated Woman and Angel point to a continued interest in classical mythology and allegorical representations. These titles suggest compositions rich in symbolism and narrative, likely executed with the polished technique characteristic of his academic background. The recurring motif of figures almost floating, as mentioned in the provided notes for The Birth of Ogier the Dane, might indicate a stylistic tendency towards creating an otherworldly or dreamlike atmosphere in these thematic pieces.

The mention of Sea Urchins Art of the World suggests an interest in natural forms, which could align with several artistic currents of the time. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the rise of the Arts and Crafts movement and Art Nouveau, both of which drew heavily on natural motifs. If this work involved "plastic, metal, and wood," as one source snippet suggests, it would be highly unusual for fine art painting of his era and might point towards decorative arts or sculpture, or perhaps a misunderstanding of the source material. However, a "naturalist style" in depicting sea urchins could simply mean a detailed, observational approach to natural subjects, perhaps incorporated into decorative designs or studies. Without more visual information, it's hard to definitively categorize, but it indicates a breadth of interest beyond purely historical or mythological scenes.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Influences

Robert Van Vorst Sewell's artistic style can be seen as a synthesis of his academic training and the prevailing artistic tastes of his time. The foundation laid by Lefebvre and Boulanger provided him with the technical proficiency to handle complex compositions and render the human form with accuracy. This academic underpinning is evident in the clarity and structure of his known works.

However, Sewell was not merely a slavish follower of academic dogma. His choice of subject matter—medieval legends, classical myths, literary scenes—aligns him with the broader Romantic and Symbolist currents that persisted alongside, and sometimes intertwined with, academic art. These movements favored imagination, emotion, and the exploration of inner worlds or ancient narratives over the straightforward depiction of contemporary life seen in Realism or the optical experiments of Impressionism.

His mural work, by its very nature, often involved allegorical or historical themes that fit within the "American Renaissance" ideal of art that could instruct and inspire. In his easel paintings, he seems to have leaned more into the romantic and poetic, creating images that were evocative and narrative-driven. The description of his work sometimes employing similar color palettes and materials across different pieces suggests a consistent artistic vision and technical approach.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Professional Life

Sewell was an active participant in the art world of his day. His studies at the Académie Julian were a starting point, but his continued involvement in exhibitions on both sides of the Atlantic demonstrates his professional ambition. Exhibiting at the Paris Salon was a significant achievement for any artist, and his participation there, along with shows at the Boston Art Club and the National Academy of Design, indicates a degree of recognition within established art circles.

The National Academy of Design (now the National Academy Museum and School) in New York was a particularly important institution for American artists. Founded in 1825 by artists like Samuel F.B. Morse and Thomas Cole, it served as an art school, an honorary association for artists, and a venue for annual exhibitions. Sewell's works being displayed there, such as The Birth of Ogier the Dane, meant they were seen by critics, collectors, and fellow artists. His works also found homes in institutional collections, including the National Academy of Design itself, the Union Club, and the Architectural League of New York, further cementing his status as a respected professional.

He also exhibited at major national events like the Pan-American Exposition (Buffalo, 1901) and the St. Louis Louisiana Purchase Exposition (1904), which were grand showcases of American industry, culture, and art. The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia, another venerable American art institution, also featured his work. These venues provided artists with crucial visibility and opportunities for patronage.

Sewell and His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Robert Van Vorst Sewell, it's useful to consider him in the context of his contemporaries. In Paris, he would have been aware of the Impressionists like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas, even if his own style diverged. His teachers, Lefebvre and Boulanger, were peers of other academic titans like Jean-Léon Gérôme and William-Adolphe Bouguereau, whose influence dominated official art for decades.

Back in America, the art scene was vibrant and diverse. In the realm of mural painting, he worked alongside figures like John La Farge, known for his innovative stained glass and murals in Trinity Church, Boston; Edwin Howland Blashfield, who decorated numerous public buildings including the Library of Congress; and Kenyon Cox, a staunch defender of classical ideals. Elihu Vedder, another distinctive artist, created powerful symbolic murals and illustrations, such as for the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám.

Among easel painters, the era boasted giants like John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler, who achieved international fame with their sophisticated portraiture and aesthetic theories. Realists like Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer captured American life with unflinching honesty. Meanwhile, American Impressionists such as Childe Hassam and Mary Cassatt adapted French Impressionism to American subjects. Sewell's work, with its literary and mythological focus, carved out a niche distinct from these, yet part of the rich tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century American art. His thematic choices might also find parallels in the work of Symbolist-leaning painters like Albert Pinkham Ryder, known for his moody, enigmatic landscapes and marine scenes.

Information regarding Sewell's direct collaborations or specific rivalries with these artists is not readily available from the provided text, but he undoubtedly operated within this dynamic and competitive artistic environment. The lack of information about his own students suggests he may have focused more on his studio practice than on teaching.

Later Years, Legacy, and Conclusion

Robert Van Vorst Sewell eventually moved from Long Island to the West Coast, a common trajectory for many seeking new opportunities or a different climate in the early 20th century. He passed away in 1924.

Today, Robert Van Vorst Sewell is remembered primarily as a skilled muralist and a painter of romantic and allegorical subjects. His work reflects the confluence of rigorous European academic training and the cultural aspirations of Gilded Age America. While the grand narratives and idealized forms of academic art and the American Renaissance fell out of favor with the rise of Modernism in the early to mid-20th century, there has been a renewed scholarly interest in this period. Artists like Sewell, who contributed significantly to the visual culture of their time, are being re-evaluated.

His mural The Canterbury Pilgrims remains an important example of large-scale decorative painting in a private American residence from that era. His easel paintings, like The Birth of Ogier the Dane, offer insights into the period's fascination with myth, legend, and romantic storytelling. Though perhaps not a radical innovator, Sewell was a consummate professional who skillfully navigated the artistic currents of his day, leaving behind a body of work that speaks to the tastes, values, and artistic practices of a transformative era in American art. His contributions to mural painting and his dedication to narrative and figurative art secure his place in the annals of American art history.