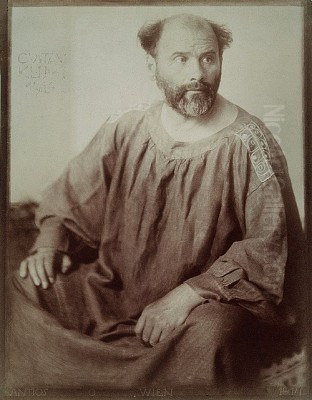

Gustav Klimt stands as one of the most significant and recognizable figures in the history of modern art. Born in Austria during the latter half of the nineteenth century, his life and work bridged the gap between academic tradition and the burgeoning avant-garde movements that would define the twentieth century. As a primary force behind the Vienna Secession and a master of Symbolism and Art Nouveau, Klimt created a unique visual language characterized by opulent decoration, sensual depictions of the human form, particularly women, and a profound exploration of life's fundamental themes. His journey from a skilled decorative painter to a controversial and celebrated modernist icon reflects the turbulent and innovative spirit of Vienna at the turn of the century.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Gustav Klimt was born on July 14, 1862, in Baumgarten, a suburb of Vienna, Austria. He was the second of seven children born to Ernst Klimt the Elder, a gold and silver engraver who had migrated from Bohemia, and Anna Klimt (née Finster), whose ambitions for a career in musical performance remained unfulfilled. Despite his father's craft, the family experienced significant financial hardship, particularly during the economic crash of 1873. This early exposure to poverty contrasted sharply with the inherent artistic talent present in the household.

Recognizing Gustav's exceptional drawing ability from a young age, his family supported his artistic inclinations. In 1876, at the remarkably young age of fourteen, Gustav passed the entrance examination for the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts (Kunstgewerbeschule), now the University of Applied Arts Vienna. He received a scholarship, easing the financial burden on his family. His younger brothers, Ernst Klimt the Younger and Georg Klimt, would later follow him into artistic professions, with Ernst becoming a painter and Georg a sculptor and craftsman.

At the Kunstgewerbeschule, Klimt studied architectural painting under Ferdinand Laufberger and later Michael Rieser and Karl Hrachowina. He received rigorous training in classical techniques, mastering figurative drawing, mural painting, and various decorative arts, including mosaic work and fresco. His instructors recognized his talent, and he quickly distinguished himself. During his studies, which lasted until 1883, he deeply absorbed the historicist styles prevalent in the grand Ringstrasse architecture projects of the time, becoming proficient in the academic manner favored by the Viennese establishment.

The Künstler-Compagnie and Early Success

While still students, Gustav Klimt, his brother Ernst, and their friend Franz Matsch formed a collective known as the "Künstler-Compagnie" (Artists' Company) around 1883. They began receiving commissions for decorative murals and architectural paintings, quickly establishing a reputation for their technical skill and adherence to the prevailing academic and historical styles. Their collaborative approach often made it difficult to distinguish individual hands in their early works.

Their commissions included significant projects for prominent buildings along Vienna's Ringstrasse. They created murals for the stairwells of the new Burgtheater (Imperial Court Theater), completed between 1886 and 1888. These paintings, depicting scenes from theatre history, were executed in a rich, detailed historical style and were highly acclaimed. For this work, the artists were awarded the Golden Order of Merit by Emperor Franz Joseph I in 1888, a significant honor that cemented their status within the Viennese art world.

Another major commission was for the spandrels and intercolumnar paintings in the grand staircase of the Kunsthistorisches Museum (Museum of Art History) in Vienna, completed around 1890-1891. These works further demonstrated their mastery of large-scale decorative schemes in the accepted academic tradition. During this period, Klimt's personal style, while technically brilliant, remained largely conventional, showing little sign of the radical departure his art would later take. The success of the Künstler-Compagnie provided financial stability but operated firmly within the conservative tastes of the era.

The Birth of the Vienna Secession

The late 19th century in Vienna saw a growing dissatisfaction among younger artists with the conservative attitudes dominating the official art institutions, particularly the Vienna Künstlerhaus (Association of Austrian Artists). This establishment favored traditional academic art and was resistant to the new artistic currents emerging across Europe, such as Impressionism, Symbolism, and Art Nouveau. Gustav Klimt, despite his early success within the system, increasingly felt constrained by its limitations.

In 1897, Klimt became a leading figure in a radical break from the Künstlerhaus. He, along with a group of like-minded artists, architects, and designers – including Koloman Moser, Josef Hoffmann, Joseph Maria Olbrich, Max Kurzweil, and Carl Moll – founded the "Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession," commonly known as the Vienna Secession. Klimt was elected its first president. The Secession aimed to create a platform for contemporary, unconventional art, both Austrian and international, free from the dictates of the academic establishment.

Their motto, "To the age its art, to art its freedom" (Der Zeit ihre Kunst, der Kunst ihre Freiheit), inscribed above the entrance of the Secession Building designed by Olbrich, encapsulated their mission. The Secession organized groundbreaking exhibitions showcasing not only the work of its members but also that of leading international avant-garde artists like Auguste Rodin, Fernand Khnopff, Jan Toorop, and Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh of the Glasgow School. These exhibitions exposed the Viennese public to modern art movements and fostered a rich dialogue between different artistic disciplines, including painting, sculpture, architecture, and the applied arts (as later championed by the Wiener Werkstätte, co-founded by Hoffmann and Moser). Klimt's leadership was crucial in establishing the Secession as a dynamic force for artistic renewal in Vienna.

The University Murals and Controversy

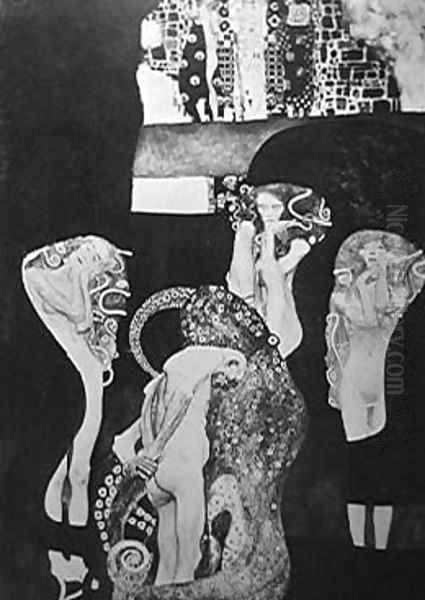

A pivotal moment in Klimt's career, marking his definitive break with public and official acceptance, came with the commission for ceiling paintings in the Great Hall (Aula) of the University of Vienna. Starting around 1894, before the Secession's founding, Klimt was tasked with creating large allegorical paintings representing Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence. His brother Ernst and Franz Matsch were also involved initially, but after Ernst's sudden death in 1892, the project dynamics shifted.

When Klimt presented his finished panel for Philosophy at the seventh Secession exhibition in 1900, it caused a scandal. Instead of a traditional, clear allegory, Klimt offered a cosmic vision of floating, intertwined figures, representing humanity adrift in a mystical universe, dominated by a sphinx-like figure emerging from nebulous space. Critics, including university professors and parliament members, condemned it as obscure, pessimistic, and even pornographic due to the nudity.

The controversy intensified with the unveiling of Medicine (1901), which depicted a column of naked, suffering figures alongside Hygieia, the goddess of health, who seemed indifferent, holding a serpent. Death loomed large in the composition. Jurisprudence (1903-1907) followed, showing a condemned man surrounded by allegorical figures of Justice, Law, and Truth, but dominated by furies and a menacing octopus-like creature. The traditional ideals of rational law seemed subverted by primal forces.

The public outcry was immense. Eighty-seven faculty members protested, and the paintings were deemed offensive and unsuitable for the university. Feeling betrayed and artistically compromised, Klimt eventually withdrew from the commission in 1905. He repaid his advance payment and reclaimed the paintings, vowing never again to accept a public commission. This episode solidified his reputation as a controversial modernist and pushed him towards private patronage, where his artistic vision could flourish without compromise. Tragically, the three University Murals were destroyed by retreating SS forces in 1945.

The Golden Phase

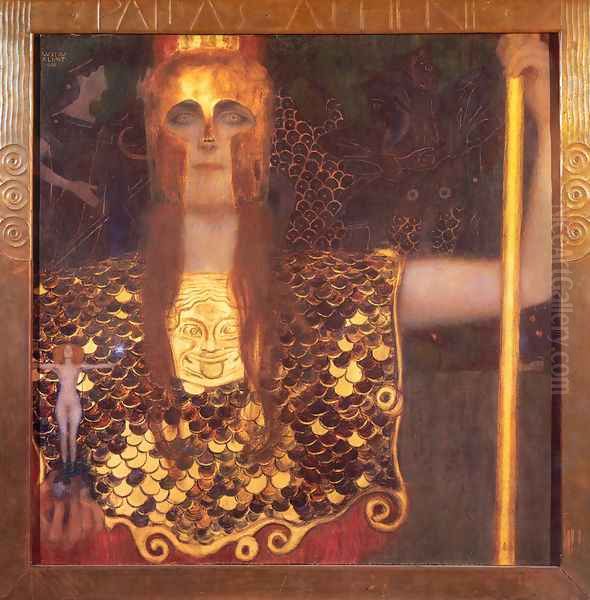

Freed from the constraints of public commissions and fueled by the Secession's spirit of innovation, Klimt entered his most celebrated and distinctive period, often referred to as the "Golden Phase" or "Golden Style." This phase, roughly spanning from the late 1890s to around 1909, is characterized by the lavish use of gold leaf, intricate ornamentation, flattened perspectives, and a synthesis of figurative realism with abstract decorative patterns.

The inspiration for this style was multifaceted. His father's profession as a gold engraver likely provided an early familiarity with the material. Travels to Ravenna, Italy, in 1903 exposed him directly to the glittering gold mosaics of Byzantine art in the Basilica di San Vitale, which profoundly impacted his aesthetic. Furthermore, influences from ancient Egyptian art, Mycenaean metalwork, and Japanese prints (Ukiyo-e), particularly their flattened spaces and decorative emphasis, are evident.

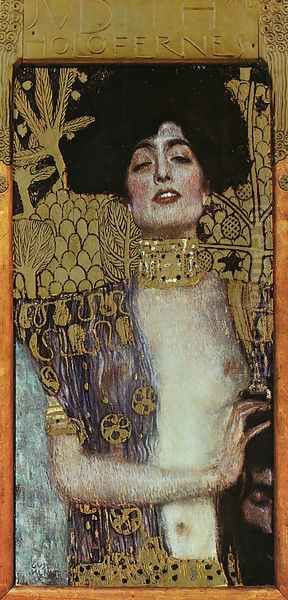

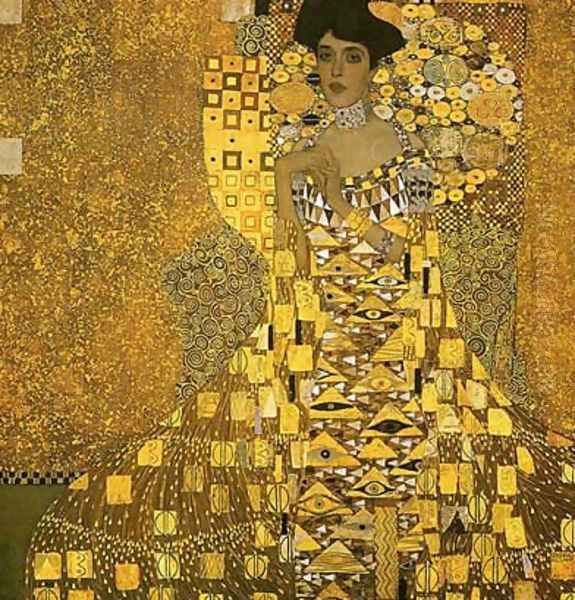

Key works from this period exemplify the Golden Style. Pallas Athene (1898), an early precursor, already features gold elements and symbolic motifs. Judith I (1901) presents the biblical heroine as a seductive femme fatale, adorned with gold jewelry against a richly patterned gold background. The iconic Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907), commissioned by the sitter's wealthy industrialist husband, immerses the subject in a shimmering mosaic of gold and silver leaf, geometric shapes, and stylized Egyptian eye motifs, blurring the line between portraiture and decorative object.

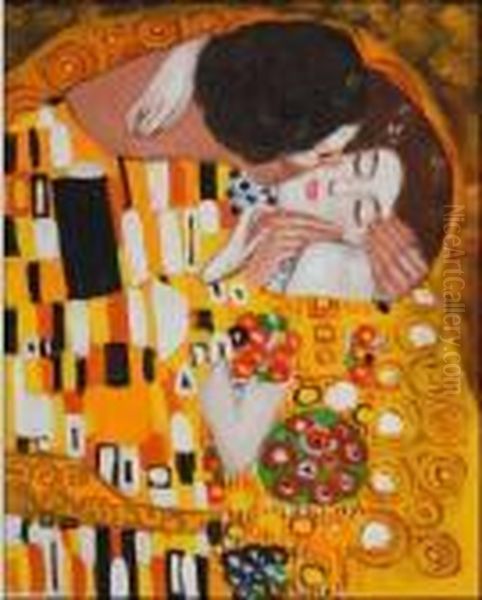

Perhaps the culmination of the Golden Phase is The Kiss (Der Kuss), painted between 1907 and 1908. This large square canvas depicts a couple locked in an embrace, kneeling on a flower-strewn precipice against a flat gold background. Their bodies are enveloped in richly patterned robes – the man's decorated with bold rectangular shapes, the woman's with swirling circles and floral motifs. While their faces and hands are rendered with tender realism, the rest of the composition dissolves into opulent pattern and texture. The painting became an immediate sensation and was purchased by the Austrian state for the Belvedere Gallery, securing its place as an icon of Viennese Art Nouveau (Jugendstil) and a universal symbol of love and ecstasy.

Themes and Subjects: The Eternal Feminine

Throughout his mature career, the female form was Klimt's central preoccupation. His work explores the multifaceted nature of femininity, portraying women as society hostesses, mythological figures, allegorical symbols, and objects of erotic desire. His depictions often blend sensuality with a sense of mystery and psychological depth, reflecting the complex attitudes towards women and sexuality prevalent in fin-de-siècle Vienna, the city of Sigmund Freud.

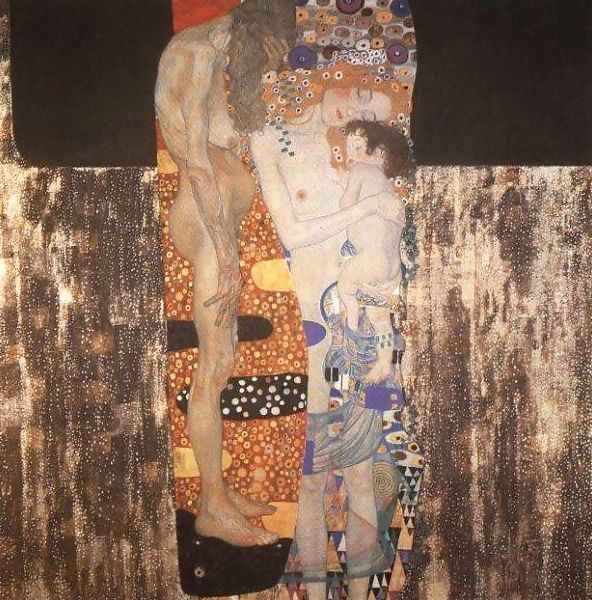

Klimt's women range from the powerful and dangerous femme fatale, as seen in Judith I, to figures embodying life cycles and universal experiences. The Three Ages of Woman (1905) contrasts the vulnerability of infancy and the decay of old age with the radiant beauty of young motherhood, all intertwined against a decorative background. Danaë (c. 1907-1908), depicts the mythological princess curled in ecstatic sleep as Zeus descends upon her in a shower of gold, a highly erotic and symbolic representation of conception.

Death and Life (designed c. 1908, executed 1915-1916) presents a stark contrast. On one side, Death appears as a skeletal figure clad in dark, cross-adorned robes, observing a vibrant cluster of intertwined human figures – men, women, and children – representing Life in all its stages, seemingly unaware of the looming presence. The figures of Life are adorned with bright, floral patterns, contrasting sharply with the somber, symbolic garb of Death. This work encapsulates Klimt's recurring engagement with the fundamental themes of existence: love, life, decay, and mortality. His exploration of these themes often employed symbolic elements – snakes, spirals, water, floral motifs – woven into the decorative fabric of his compositions.

Portraiture: Society and Intimacy

Beyond his allegorical and mythological works, Klimt was a highly sought-after portrait painter, particularly among the affluent, progressive Jewish bourgeoisie of Vienna who became his primary patrons after the University Murals scandal. His portraits, especially those of women, are remarkable for their blend of realistic likeness in the face and hands with highly stylized, decoratively flattened rendering of clothing and background, often incorporating elements from his Golden Phase.

His subjects included prominent figures like Serena Lederer, Fritza Riedler, and perhaps most famously, Adele Bloch-Bauer, whom he painted twice. Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907) is the quintessential example of his Golden Style portraiture. The later Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II (1912) shows a shift away from gold leaf towards brighter colors and more painterly patterns, reflecting the influence of younger artists like Henri Matisse and the Fauves.

A particularly significant relationship was with Emilie Flöge, a successful fashion designer and businesswoman who ran a prominent Viennese haute couture salon with her sisters. Klimt and Flöge were lifelong companions, though the exact nature of their relationship remains debated. He painted her portrait several times, notably in a striking full-length depiction from 1902 where she wears a long, patterned gown of her own design, standing confidently against an abstract blue background. Klimt's portraits capture not just the likeness but also the social standing, personality, and modern sensibility of his sitters, embedding them within the rich decorative context of his unique style.

Landscape Painting: Retreat and Reflection

While best known for his figurative works, Klimt was also a dedicated landscape painter, producing a significant body of work in this genre, primarily during his summer holidays spent on the shores of the Attersee (Lake Atter) in the Salzkammergut region of Austria. These landscapes offer a different perspective on his art, often characterized by a sense of tranquility and a focus on capturing the patterns and textures of nature.

Unlike the Impressionists, Klimt was generally uninterested in fleeting atmospheric effects or human presence in his landscapes. Instead, he often adopted a high viewpoint, flattening the perspective and compressing space, transforming fields, forests, and water surfaces into dense, mosaic-like tapestries of color and form. Many of his landscapes are painted in a distinctive square format, reinforcing their decorative, object-like quality.

Works like Beechwood (1902) or Apple Tree I (1912) show his fascination with the repetitive patterns of tree trunks, leaves, and blossoms. He experimented with techniques reminiscent of Pointillism, using small dabs of color to build up surfaces, but always subordinated these techniques to his overall sense of design and pattern. The Attersee landscapes reveal a more contemplative side of Klimt, a retreat from the intensity of his Viennese life and figurative subjects into an immersive engagement with the natural world, rendered through his unique decorative lens. These works demonstrate his versatility and his consistent exploration of pattern and surface across different genres.

Influence and Mentorship: Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka

Klimt was not only a leading artist but also a generous mentor to younger talents emerging in Vienna. His most famous protégé was Egon Schiele, a brilliant and provocative draftsman and painter whose raw, expressive style would become central to Austrian Expressionism. Schiele sought out Klimt in 1907, and Klimt took the younger artist under his wing. He purchased Schiele's drawings, exchanged works with him, arranged models, and introduced him to potential patrons and the Wiener Werkstätte.

Klimt's influence is visible in Schiele's early work, particularly in the decorative elements and elongated figures. However, Schiele rapidly developed his own highly personal and often disturbing style, characterized by angular lines, distorted bodies, and intense psychological exploration. Despite their stylistic divergence, the two artists maintained a relationship of deep mutual respect. When Klimt died in 1918, Schiele expressed profound grief and himself succumbed to the same Spanish flu pandemic just months later.

Another major figure of Austrian Expressionism, Oskar Kokoschka, also emerged from Klimt's circle, though their relationship was less one of direct mentorship. Kokoschka's turbulent, psychologically charged portraits and paintings stood in stark contrast to Klimt's decorative elegance. Yet, both Schiele and Kokoschka, while forging their own paths, operated within the artistic environment Klimt had helped to create through the Secession, challenging conventions and pushing the boundaries of representation. Klimt's support for younger artists, even those whose styles differed radically from his own, highlights his commitment to artistic freedom and innovation.

Connections and Contemporaries: A Viennese Nexus

Gustav Klimt operated at the vibrant heart of Viennese cultural life during a period of extraordinary intellectual and artistic ferment. His activities, particularly through the Secession, brought him into contact with leading figures across various disciplines. He interacted with architects like Josef Hoffmann and Joseph Maria Olbrich, whose designs for the Secession building and later the Wiener Werkstätte shared Klimt's interest in integrated artistic environments (Gesamtkunstwerk).

The Secession exhibitions facilitated crucial international exchanges. Klimt met the renowned French sculptor Auguste Rodin during Rodin's visit to Vienna for a Secession exhibition in 1902. The influence of international artists exhibited by the Secession, such as the Belgian Symbolist Fernand Khnopff, the Dutch Symbolist Jan Toorop, and the Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler, can be traced in Klimt's work. Conversely, Klimt's art, particularly the famous Beethoven Frieze created for the 1902 Secession exhibition dedicated to the composer (and featuring a sculpture by Max Klinger), resonated with contemporaries like the composer Gustav Mahler, whose music often shared a similar intensity and exploration of profound themes.

Klimt's work also shows an awareness of broader European trends. Echoes of French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, particularly the decorative qualities found in the work of artists like Vincent van Gogh or Paul Gauguin, can be discerned. The flattened perspectives and decorative emphasis also connect him to artists like James McNeill Whistler. While perhaps not directly interacting with Sigmund Freud, Klimt's exploration of eroticism, psychology, and the subconscious resonates deeply with the psychoanalytic theories developing simultaneously in the same city, reflecting a shared cultural preoccupation with the inner life. His circle also included photographers like Madame d'Ora (Dora Kallmus), who documented the artist and his milieu.

Later Years and Legacy

Following the Golden Phase, Klimt's style continued to evolve. While the opulence of gold leaf receded, his interest in pattern and color intensified. His later works, from around 1910 onwards, often feature brighter, more vibrant palettes and looser brushwork, showing an engagement with contemporary French movements like Fauvism, particularly the work of Henri Matisse. His later portraits and allegorical paintings retain their decorative richness but possess a more painterly quality.

Klimt remained a highly respected, if still sometimes controversial, figure in the Viennese art world. He continued to paint prolifically, focusing on portraits, allegories, and his beloved Attersee landscapes. He received honors both domestically and internationally, including becoming an honorary member of the Universities of Munich and Vienna (despite the earlier mural controversy).

In January 1918, Gustav Klimt suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. While recovering in the hospital, he contracted pneumonia as a result of the devastating Spanish flu pandemic sweeping across Europe. He died on February 6, 1918, at the age of 55. His death, followed closely by that of Egon Schiele later the same year, marked the end of an era for Viennese art. He was buried in the Hietzing Cemetery in Vienna.

Gustav Klimt left behind a powerful legacy. His unique synthesis of Symbolism, Art Nouveau decoration, and psychological depth created some of the most iconic images of modern art. He profoundly influenced Austrian Expressionism and continues to fascinate audiences worldwide. His works command enormous prices at auction – Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I was famously acquired by Ronald Lauder for the Neue Galerie in New York in 2006 for a reported $135 million, then a record price for a painting. Klimt's art remains a testament to the dazzling, complex, and ultimately fragile brilliance of Vienna at the dawn of the modern age.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Gustav Klimt's artistic journey encapsulates the transition from 19th-century historicism to 20th-century modernism. As a founder and leader of the Vienna Secession, he championed artistic freedom and innovation, challenging the conservative establishment and opening Vienna to international avant-garde currents. His distinctive style, particularly the celebrated Golden Phase, fused opulent decoration inspired by diverse historical sources with a profound exploration of the human condition – focusing on themes of love, sensuality, life, and death, often through the lens of the female form.

Though controversial in his time, Klimt created works of enduring beauty and power. Masterpieces like The Kiss and the portraits of Adele Bloch-Bauer have become globally recognized icons, celebrated for their intricate detail, symbolic richness, and unique blend of realism and abstraction. His mentorship of Egon Schiele fostered the next generation of Austrian artists, while his landscapes reveal a quieter, contemplative aspect of his genius. Klimt's legacy lies not only in his stunning visual creations but also in his role as a pivotal figure who navigated and shaped the complex cultural landscape of fin-de-siècle Vienna, leaving an indelible mark on the history of art.