Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, an enigmatic yet pivotal figure of the 16th century, stands as a testament to the era's burgeoning curiosity about the natural world and the uncharted territories beyond European shores. Born circa 1533 in Dieppe, France, and passing away in London in 1588, Le Moyne's life was a tapestry woven with threads of artistic endeavor, perilous exploration, religious conviction, and courtly patronage. His legacy, though for a time obscured, has been rightfully re-established, revealing him as a significant cartographer, an accomplished botanical illustrator, and one of the earliest European artists to visually document the flora, fauna, and indigenous peoples of North America.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in Dieppe

Dieppe, in the mid-16th century, was not merely a coastal town but a vibrant hub of maritime activity, cartography, and artistic production. Its renowned school of mapmakers and illuminators likely provided the fertile ground for Le Moyne's initial artistic training. While specific details of his apprenticeship remain elusive, the sophisticated draftsmanship and keen observational skills evident in his later work suggest a rigorous education in the prevailing artistic traditions of France, which blended late Gothic precision with emerging Renaissance naturalism.

As a Huguenot, a French Protestant, Le Moyne's life was inevitably shaped by the religious turmoil that gripped France during this period. The Wars of Religion created an environment of persecution and uncertainty for Protestants, prompting many, including Le Moyne, to seek opportunities and refuge elsewhere. This religious affiliation would also be instrumental in his selection for a significant transatlantic voyage.

The Florida Expedition: Chronicler of a New World

The most defining chapter of Le Moyne's life began in 1564 when he was appointed as the official artist and cartographer for a French Huguenot expedition to Florida. Led by René Goulaine de Laudonnière, under the broader initiative of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny who aimed to establish a Protestant haven in the New World, the expedition sought to found a permanent colony, Fort Caroline, near present-day Jacksonville. Le Moyne's explicit commission was to map the territory, document its natural resources, and record the customs and appearance of the native inhabitants.

A Voyage into the Unknown

The journey itself was an arduous undertaking, fraught with the dangers common to 16th-century sea travel. Upon arrival, Le Moyne diligently set about his tasks. His drawings and watercolors from this period, though many originals are now lost, formed the basis for later engravings that offer an invaluable, if European-filtered, glimpse into a world previously unseen by most Europeans. He was one of the first, alongside perhaps John White who would later document the Roanoke Colony, to systematically record the North American landscape and its indigenous cultures.

Documenting the Timucua People

Le Moyne's depictions of the Timucua, the indigenous people of the region, are particularly significant. He illustrated their villages, agricultural practices, hunting techniques, ceremonies, and social structures. These images, later popularized by the Flemish engraver Theodore de Bry, showed the Timucua as a sophisticated society with established customs. For instance, his works depicted their methods of preparing land for cultivation, their communal feasting, and their elaborate rituals for warfare and mourning.

One notable, and sometimes debated, observation recorded by Le Moyne concerned individuals he described as "hermaphrodites" among the Timucua. These individuals, likely two-spirit people or those fulfilling specific social roles not easily categorized by European gender norms, were depicted as performing heavy labor and accompanying chiefs. While Le Moyne's interpretation was through a 16th-century European lens, his record provides a rare, early ethnographic observation.

The Flora and Fauna of a Verdant Land

Beyond the human inhabitants, Le Moyne was captivated by the rich biodiversity of Florida. He meticulously sketched the unfamiliar plants and animals, from vibrant flowers and fruits to exotic birds and reptiles. These botanical and zoological studies were not mere curiosities; they held potential scientific and economic value for the European sponsors of the expedition. His attention to detail in these renderings foreshadowed his later career as a dedicated botanical artist.

Cartographic Endeavors

As the expedition's cartographer, Le Moyne was responsible for creating maps of the coastline and the interior regions explored by the French. While his original maps from Florida have not survived, a map attributed to him, engraved by Theodore de Bry, titled Floridae Americae Provinciae Recens & exactissima descriptio, was published in 1591. This map was one of the earliest and most detailed representations of the Florida peninsula and its environs, influencing European understanding of the region's geography for years to come. It depicted rivers, capes, and the locations of indigenous settlements, crucial information for future navigators and colonizers.

The Fort Caroline Tragedy and Miraculous Escape

The French Huguenot dream in Florida was short-lived. In September 1565, a Spanish force led by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, dispatched to eradicate the Protestant presence and assert Spanish claims to the territory, attacked Fort Caroline. The settlement was overrun, and most of its inhabitants were massacred. Le Moyne was among the few who managed to escape the slaughter. After a harrowing journey, which included navigating treacherous waters and enduring starvation, he eventually made his way back to France. The trauma of this event, and the loss of many of his original Florida drawings (though he managed to save some), undoubtedly left a profound mark on him.

A New Chapter in England: Patronage and Botanical Artistry

Following his return to France, the ongoing religious persecution likely made it untenable for Le Moyne to remain. By the late 1560s or early 1570s, he sought refuge in England, joining a growing community of Huguenot exiles in London. Here, his artistic talents found new avenues for expression, particularly under the patronage of influential figures at the Elizabethan court.

Esteemed Patrons: Sir Walter Raleigh and Lady Mary Sidney

In England, Le Moyne came under the patronage of Sir Walter Raleigh, the famed courtier, explorer, and colonizer, and Lady Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke, a prominent literary figure and sister of Sir Philip Sidney. Raleigh, deeply involved in English colonial ambitions in North America, would have recognized the immense value of Le Moyne's firsthand experience and artistic records of the New World. It is believed that Raleigh encouraged Le Moyne to reconstruct his Florida drawings and to write an account of the expedition.

This connection also brought Le Moyne into contact with John White, the artist and later governor of the ill-fated Roanoke Colony. White, who also produced significant watercolors of Native Americans and the North American environment, likely consulted with Le Moyne, sharing knowledge and perhaps even artistic techniques. The visual records of both artists, though distinct in style, form the cornerstone of our understanding of early English encounters in North America.

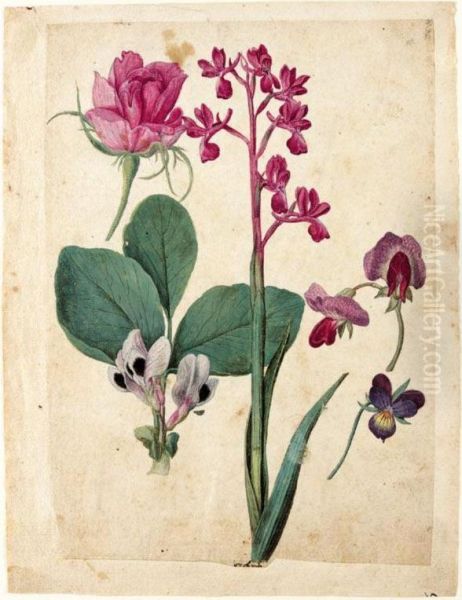

La Clef des Champs: A Key to the Fields

During his time in England, Le Moyne dedicated himself increasingly to botanical illustration. His most notable published work from this period is La Clef des Champs, pour trouver plusieurs animaux, tant bestes qu'oyseaux, avec plusieurs fleurs et fruitz (The Key to the Fields, to find several animals, both beasts and birds, with several flowers and fruits), published in London in 1586. This small volume contained a series of woodcut illustrations of plants, fruits, and animals, intended as a pattern book for artists and craftsmen, such as embroiderers and goldsmiths. While the woodcuts lack the finesse of his watercolors, La Clef des Champs demonstrates his commitment to the accurate depiction of natural subjects and his desire to disseminate this knowledge.

His detailed and exquisitely rendered watercolors of flowers, fruits, and insects from this period, many of which are now housed in institutions like the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum, showcase his mastery. These works are characterized by their scientific accuracy, delicate coloring, and elegant composition, placing him among the leading botanical artists of his time, alongside contemporaries like Joris Hoefnagel, whose meticulous miniatures for Emperor Rudolf II set a high standard for natural history illustration.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Representative Works

Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues's artistic output is characterized by a blend of meticulous observation, scientific accuracy, and a refined aesthetic sensibility. His style forms a bridge between the traditions of late medieval manuscript illumination and the burgeoning field of naturalistic botanical and zoological illustration that would flourish in the 17th century with artists like Jacques de Gheyn II and Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder.

Precision and Scientific Observation

At the core of Le Moyne's art was a profound respect for the natural world. Whether depicting a Timucuan warrior, a Florida alligator, or an English garden flower, he strove for accuracy in form, color, and detail. His botanical illustrations, in particular, often show different stages of a plant's life cycle or include details of its structure that would be of interest to a botanist. This scientific approach was shared by other pioneering botanical illustrators of the era, such as Leonhart Fuchs in Germany, whose De Historia Stirpium Commentarii Insignes (1542) with its woodcuts by artists like Albrecht Meyer and Heinrich Füllmaurer, set a new standard for botanical representation.

Mediums and Methods

Le Moyne primarily worked in watercolor and gouache (bodycolor) on vellum or paper, often with preparatory sketches in black lead or ink. His technique involved delicate washes of color, built up in layers to achieve subtle gradations of tone and texture. He often outlined his subjects with fine pen lines, adding clarity and definition. In some of his more elaborate floral pieces, he incorporated insects like butterflies, caterpillars, or beetles, adding a touch of liveliness and ecological context, a practice also seen in the work of Joris Hoefnagel. The use of vellum, a smooth and durable surface, allowed for the exquisite detail that characterizes his best work.

Representative Works

While many of Le Moyne's original Florida drawings are lost, their essence survives in the engravings published by Theodore de Bry. Key works and series include:

The Florida Watercolors (reconstructions and surviving originals): These depict scenes such as René de Laudonnière and the Indian Chief Athore Visit Ribaut's Column, showcasing interactions between the French and the Timucua, and The Timucua Indians Hunting Alligators, illustrating local practices. These images, though filtered through a European perspective, are invaluable ethnographic documents.

Engravings in Theodore de Bry's Brevis narratio eorum quae in Florida Americae provincia Gallis acciderunt (A Brief Narration of Those Things Which Befell the French in the Province of Florida in America), published in 1591 as part of his Grand Voyages series. This volume, containing 42 engraved plates after Le Moyne's drawings, along with Le Moyne's narrative, widely disseminated his Florida experiences and imagery throughout Europe. De Bry, sometimes with the help of other engravers like Gijsbert van Veen, took liberties in adapting the images for a European audience, often classicizing the figures of the Native Americans.

La Clef des Champs (1586): This pattern book, with its woodcuts of flora and fauna, represents his published contribution to applied arts.

Botanical Watercolors: A significant body of work, created primarily in England. Masterpieces such as A Sheet of Studies of Flowers: A Rose, a Heartsease, a Sweet Pea, a Garden Pea, and a Lax-flowered Orchid, Common Borage, A Double Vine of Purple and Green Grapes, Peony, Wild Gladiolus and stag beetle, Clove Pinks (Dianthus caryophyllus), and Damask Rose are celebrated for their beauty and accuracy. These works rival the best of European botanical art of the period and show an artist deeply attuned to the nuances of plant form and color. His approach can be compared to the work of French naturalist Pierre Belon, who also illustrated his travel and natural history accounts.

Collaborations and Contemporaries: A Network of Art and Knowledge

Le Moyne did not work in isolation. His career was intertwined with several key figures who helped shape and disseminate his work, and he operated within a broader European artistic and intellectual milieu that valued exploration and natural history.

Theodore de Bry: The Great Disseminator

The collaboration with Theodore de Bry was crucial for Le Moyne's posthumous fame regarding his Florida experiences. De Bry, a Flemish engraver and publisher who had also settled in Frankfurt to escape religious persecution, was compiling his ambitious Grand Voyages, a multi-volume collection of illustrated accounts of explorations to the Americas and the East Indies. He acquired Le Moyne's Florida drawings and narrative, possibly through Sir Walter Raleigh's circle after Le Moyne's death. De Bry's engravings, while not always faithful reproductions, ensured that Le Moyne's vision of Florida reached a wide European audience, shaping perceptions of the New World for generations.

Crispijn de Passe the Elder and the Dutch Connection

Le Moyne's exquisite flower paintings, likely known within artistic circles in London, are believed to have influenced the development of Dutch flower painting. Crispijn de Passe the Elder, a Flemish engraver and publisher who also spent time in London, is thought to have known Le Moyne's work. De Passe's own influential botanical publications, such as Hortus Floridus (1614), which featured engravings by his sons Simon, Willem, and Crispijn the Younger, show stylistic and thematic similarities to Le Moyne's approach. It is plausible that Le Moyne's detailed and naturalistic depictions of individual flowers contributed to the emerging genre of the flower piece in the Netherlands, later perfected by artists like Jan Brueghel the Elder and Roelandt Savery.

John White: A Fellow Chronicler of the New World

The connection with John White is particularly intriguing. Both artists were tasked with documenting English (or in Le Moyne's case, initially French) encounters in North America. White's watercolors of the Algonquian peoples of coastal North Carolina and the local flora and fauna are, like Le Moyne's, foundational documents. Given their contemporaneous presence in Raleigh's circle, it is highly probable they exchanged information. White's map of the southeastern coast of North America shows familiarity with Le Moyne's cartography of Florida. The works of both artists were also engraved and published by Theodore de Bry, further linking their legacies.

Other Artistic Currents and Figures

Le Moyne's work can be situated within broader Renaissance trends. The drive to catalogue and understand the natural world was evident in the work of naturalists like Conrad Gessner in Switzerland and Ulisse Aldrovandi in Italy, both of whom amassed vast collections and commissioned numerous illustrations. In England, the court of Elizabeth I fostered a climate of artistic patronage, with miniaturists like Nicholas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver creating exquisite portraits, and larger-scale portraitists like Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger documenting the era's elite. While Le Moyne's focus was different, he operated within this vibrant artistic environment. His meticulous technique shares some affinities with the detailed work of manuscript illuminators, a tradition still alive in the 16th century, and with the emerging specialization in natural history illustration seen in artists across Europe, from Hans Weiditz in Germany (illustrator for Otto Brunfels's Herbarum vivae eicones) to the artists working for the Plantin Press in Antwerp.

Historical Evaluation and Enduring Legacy

Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues's contributions to art, ethnography, cartography, and natural history are multifaceted. For centuries, his work was primarily known through de Bry's engravings, but the rediscovery and study of his original watercolors have allowed for a fuller appreciation of his artistic skill and historical importance.

Pioneer in Ethnographic and Natural History Illustration

Le Moyne was among the very first European artists to provide a comprehensive visual record of a specific region of North America and its indigenous inhabitants. His images, despite their inherent European biases and the later adaptations by de Bry, offer invaluable insights into the Timucua culture at the point of European contact. Similarly, his depictions of New World flora and fauna were pioneering efforts in documenting the biodiversity of the Americas.

Influence on Botanical Art

His botanical watercolors, created with remarkable precision and aesthetic grace, position him as a key figure in the history of botanical illustration. His work predates the great flourishing of Dutch flower painting in the 17th century and is considered to have contributed to its development. The elegance and accuracy of his plant portraits set a high standard and demonstrate the growing interest in botany during the Renaissance, not just for medicinal purposes but also for its intrinsic beauty and scientific interest.

Controversies and Interpretations

Modern scholarship has critically examined Le Moyne's work, particularly the depictions of the Timucua. Some historians argue that his images, and especially de Bry's engravings, tend to idealize or classicize the Native Americans, fitting them into European aesthetic conventions rather than presenting a wholly objective record. There are also debates about the accuracy of certain details and the extent to which the images served colonial agendas by portraying the New World as a fertile land ripe for exploitation. These critical perspectives are essential for a nuanced understanding of his work within its historical context.

Modern Rediscovery, Exhibitions, and Publications

The 20th and 21st centuries have seen a resurgence of interest in Le Moyne. Significant exhibitions have showcased his surviving works, such as those at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Scholarly publications, notably The Work of Jacques Le Moyne De Morgues: A Huguenot Artist in France, Florida and England (1977) edited by Paul Hulton, have meticulously cataloged and analyzed his oeuvre. His works continue to fetch high prices at auction, underscoring their rarity and artistic merit.

Conclusion: A Multifaceted Renaissance Man

Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues was more than just an artist; he was an explorer, a cartographer, a naturalist, and a survivor. His life journey took him from the artistic centers of France to the uncharted shores of Florida and finally to the sophisticated court of Elizabethan England. Through his art, he provided Europe with some of its earliest and most vivid glimpses of the New World, its people, and its natural wonders. His meticulous botanical illustrations capture the beauty and diversity of the plant kingdom with scientific precision and artistic flair. Though shaped by the perspectives and limitations of his time, Le Moyne's work remains an invaluable legacy, a visual chronicle of a pivotal era of exploration, conflict, and burgeoning scientific inquiry. His contributions continue to inform our understanding of 16th-century art, ethnography, and the complex history of European encounters with the Americas.