Jaroslav Král (1883-1942) stands as a pivotal figure in the narrative of Czech modern art. His life, tragically cut short, spanned a period of immense artistic ferment and profound socio-political upheaval in Europe. Král's oeuvre is characterized by a dynamic evolution of style, a deep engagement with the artistic currents of his era, and an unwavering commitment to expressing the human condition, often imbued with a poignant social critique. From his early explorations influenced by Impressionism and Symbolism to his mature works that embraced Cubist principles, Neoclassicism, and a profound humanism, Král forged a unique artistic identity that continues to resonate. This exploration delves into his life, his artistic journey, the influences that shaped him, his significant works, and his enduring legacy within the rich tapestry of 20th-century European art.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

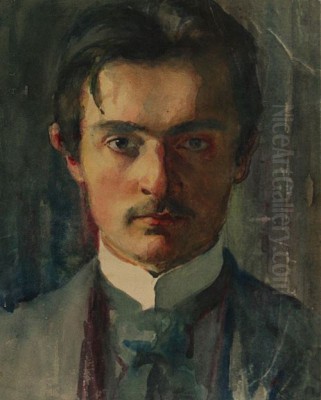

Born in 1883 in Malesovice, a small town in Moravia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Jaroslav Král's early life set the stage for his later artistic pursuits. The cultural environment of the Czech lands at the turn of the century was vibrant, with a growing sense of national identity and an increasing openness to international artistic trends. Král's innate talent and passion for art led him to Prague, the burgeoning cultural heart of Bohemia. He enrolled in the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Prague (Akademie výtvarných umění v Praze), an institution that had nurtured many of the leading figures of Czech art.

During his formative years at the Academy, Král would have been exposed to a curriculum that, while rooted in academic tradition, was increasingly being challenged by new artistic ideas emanating from Paris, Vienna, and Berlin. Artists like Max Švabinský, Vojtěch Hynais, and Hanuš Schwaiger were influential teachers at the Academy, representing various strands from academic realism to Art Nouveau and Symbolism. It was in this environment that Král began to hone his technical skills and develop his artistic voice. His early works from this period, though less documented, likely reflected the prevailing influences of late Impressionism and the evocative, often melancholic, tendencies of Symbolism, movements that were captivating many young artists across Europe, including contemporaries like Jan Preisler in Bohemia.

The Dawn of a Modernist Vision: Impressionism, Symbolism, and Early Explorations

The first decade of the 20th century was a period of intense artistic experimentation for Jaroslav Král. Like many of his generation, he was initially captivated by the atmospheric qualities of Impressionism, with its emphasis on light, color, and capturing fleeting moments. This influence can be discerned in his handling of color and his sensitivity to the nuances of the natural world. Simultaneously, the introspective and dreamlike qualities of Symbolism, which sought to express deeper emotional and spiritual truths beyond mere surface representation, also left a significant mark on his developing style.

His early works, such as Odpořujivá rodina (often translated as The Repulsive Family or The Resistant Family) from 1909, begin to show a departure from purely imitative art. This piece, while perhaps still retaining some symbolist undertones in its title and potential mood, hints at an artist grappling with more complex compositions and psychological depth. Another notable work from this early phase is Návrat z polí (Return from the Fields) of 1913. This painting demonstrates Král's burgeoning interest in the interplay of complementary colors and unique compositional arrangements, suggesting an artist already looking beyond established conventions and beginning to absorb the structural innovations that were transforming European art. These early explorations laid the groundwork for his more decisive engagement with modernism.

Embracing Cubism and the Impact of War

The period leading up to and including the First World War marked a significant turning point in Král's artistic development. The revolutionary principles of Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in Paris, began to permeate the European art scene, and Czech artists were among the most enthusiastic and original adopters of this new visual language. Král, while perhaps not a doctrinaire Cubist in the vein of Emil Filla or Bohumil Kubišta, was clearly influenced by its deconstruction of form and its emphasis on geometric structure.

Works like Hlava staré (Head of an Old Woman) and Lávora (Washbasin), both dated 1912, exhibit distinct Cubist leanings. These pieces show his exploration of faceted forms, simplified planes, and a muted palette, characteristic of early Cubist explorations. The influence of Paul Cézanne, whose structural approach to painting was a crucial precursor to Cubism, can also be felt in Král's attempts to render volume and space through carefully modulated color and form.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 profoundly impacted Král, as it did countless artists across Europe. The war's devastation and the societal anxieties it engendered found expression in his art, which began to incorporate elements of social critique. Paintings such as Hlava stavebníhoho architekta (Head of a Construction Architect) from 1914 and Výraz (Expression) from 1915 reflect this shift. These works, while still engaging with modernist formal concerns, carry a weightier, more somber tone, hinting at the psychological and social repercussions of the conflict. The expressive distortion and emotional intensity in some of these pieces also suggest an affinity with Expressionist currents, which were gaining traction in Central Europe, championed by artists like Edvard Munch and groups such as Die Brücke in Germany.

The Interwar Period: Social Themes, Family, and Neoclassical Echoes

The 1920s, following the establishment of an independent Czechoslovakia, was a period of cultural flourishing and artistic innovation. For Jaroslav Král, this decade saw a further evolution in his style and thematic concerns. While the formal lessons of Cubism remained, his focus increasingly turned towards social themes, the depiction of family life, and the human figure, particularly women. His art from this period often features a distinctive blend of modernist simplification with a newfound lyricism and a more accessible humanism.

Works like Piják (The Drinker, 1922-1923), Rodina (Family, 1922-1923), and V sedi večer (In Grey Evening/Evening in Grey, 1923) are representative of this phase. These paintings often employ cool color palettes and simplified, almost sculptural, geometric forms to convey a sense of introspection or quiet drama within everyday scenes. Král's figures, though stylized, possess a tangible presence and emotional depth, reflecting his concern for the social fabric and the lives of ordinary people.

A significant development in the 1920s and into the 1930s was Král's growing interest in Neoclassicism. This "return to order," as it was termed, was a broader European trend, a reaction against the perceived excesses of pre-war avant-gardism, and can be seen in the work of artists like Picasso himself during his classical period, and in Italy with artists like Giorgio de Chirico. For Král, this manifested in a greater emphasis on harmonious compositions, rounded forms, and a more idealized, though still modern, depiction of the human body. His portrayals of women became particularly prominent, often characterized by soft curves, gentle modeling, and a non-classical, yet timeless, perspective.

Paintings such as Pradedlina (Great-Grandmother/Ancestress, 1923) and Matka země (Mother Earth, 1926, also referred to as Zemská matka) exemplify this direction. These works often depict female figures with a monumental, nurturing quality, rendered with柔和的色彩 and a dreamlike atmosphere. Zátiško s kyticí (Still Life with a Bouquet) from 1929 is another key work, celebrated for its delicate color harmonies, its ethereal light, and its almost otherworldly ambiance, showcasing Král's mastery in creating mood through subtle visual means. His unique approach to light and color, often creating a soft, diffused glow, became a hallmark of his style during this period.

Controversy and Continued Development in the 1930s

The 1930s saw Král continue to refine his distinctive style, often focusing on themes of domesticity, femininity, and the enduring rhythms of life. His work Sklizeň (Harvest) from 1934, for instance, uses geometricized forms and soft colors to depict female figures in a rural setting, emphasizing their central role and connection to the land. The composition is balanced, and the figures, though stylized, exude a sense of calm strength.

However, this period was not without its challenges and controversies. The painting Španělská matrona (Spanish Matron), dated 1938, reportedly caused a stir within the Czech art community. Created against the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War and the rising tide of fascism in Europe, this work likely carried strong political undertones. While specific details of the controversy are not fully elaborated in the provided snippets, it's plausible that its Neoclassical style, combined with a potentially charged subject matter, provoked debate about the role of art in a politically turbulent era. Král's decision to engage with such themes, even indirectly, underscores his awareness of and response to the world around him.

During this time, Král was an active participant in the Czech art scene. He was associated with the "Friends of Art Club" (Klub přátel umění) in Prague, becoming one of its noted creative figures. He also collaborated and exhibited with fellow artists. His contemporary, Jan Zrzavý, another significant Czech modernist known for his lyrical, often melancholic style, shared certain affinities with Král, particularly in their mutual interest in classical figuration and idealized forms, albeit expressed through distinct personal idioms. Král also interacted with other artists like Karel Jílek and Jan Šima within various artistic societies, contributing to the dynamic exchange of ideas that characterized Czech modernism. The influence of other Czech modernists like Josef Čapek (brother of the writer Karel Čapek and a key figure in Czech Cubism), Antonín Procházka, and Jan Konůš, who also explored Cubism and Symbolism, would have been part of the artistic milieu in which Král operated.

The Darkening Horizon: Art in the Shadow of War

The late 1930s and the outbreak of World War II cast a long, dark shadow over Europe, and Czechoslovakia was directly impacted by Nazi aggression, culminating in its occupation. For Jaroslav Král, this period brought a profound shift in the thematic content of his work. The earlier focus on idyllic family scenes and lyrical portrayals of women gave way to more somber reflections on escape, loss, and the longing for home and peace.

His art became a form of quiet resistance, a testament to the enduring human spirit in the face of oppression. Works such as Spáči v sedi (Sleepers in Grey/Sitting) from 1940, Píseň domova (Song of Home), variously dated to 1941 or 1942, and Spáčová rodina (Sleeping Family) from 1942, are poignant expressions of this period. These paintings often convey a sense of vulnerability, anxiety, and a deep yearning for solace. The figures are often depicted in enclosed spaces, huddled together, their forms simplified and their expressions conveying a quiet sorrow or a fragile hope. The color palettes tend to be more subdued, reflecting the grim realities of the time.

Král's commitment to social commentary, evident in his earlier works, took on a new urgency during the war. Some accounts suggest he painted murals in a Slovenian church with strong anti-fascist imagery, a courageous act given the political climate. His art from these final years serves as a powerful reminder of the human cost of conflict and the artist's role as a witness and a voice for the oppressed.

Multifaceted Talents: Beyond the Easel

Interestingly, the name Jaroslav Král is associated with activities beyond the realm of painting, suggesting a multifaceted individual or perhaps the presence of contemporaries with the same name active in different fields. One such mention pertains to a Jaroslav Král involved in a disciplinary investigation within a Czech teachers' association. This individual was reportedly accused of "inciting and spreading false information" in the teachers' magazine Učitelstvické noviny. While the outcome of this investigation is unclear, the incident was considered significant in the history of Czech education.

Another Jaroslav Král is noted as having been the bassist for the popular Czech band led by Karel Vlach. This orchestra was a prominent feature of the Czech music scene, and its recordings were widely disseminated. The snippet mentions that due to changes in radio broadcast bands, their programs became difficult for Czech and Hungarian audiences to receive. If this refers to the same Jaroslav Král, the artist, it would paint a picture of an individual with remarkably diverse talents, active in both the visual arts and popular music. However, without further corroborating evidence linking these activities directly to the painter, it's also possible these refer to different individuals. The primary historical record firmly establishes Jaroslav Král the painter as a significant modernist artist. The provided information, however, prompts us to consider these other dimensions attributed to the name.

Artistic Influences and Connections: A Wider Circle

Jaroslav Král's artistic journey was shaped by a confluence of influences, both Czech and international. As mentioned, the impact of Pablo Picasso and Paul Cézanne was crucial, particularly in his engagement with Cubist principles and structural form. The broader currents of Symbolism and Expressionism also informed his early development.

Within the Czech context, he was part of a vibrant generation of artists who were forging a distinctly modern Czech art. Besides Jan Zrzavý, Josef Čapek, Emil Filla, Bohumil Kubišta, Antonín Procházka, and Jan Konůš, other important figures included Václav Špála, known for his vibrant Fauvist-inspired landscapes and still lifes, and the sculptor Otto Gutfreund, a pioneer of Cubist sculpture. The artistic climate was one of intense dialogue and exchange, with groups like Osma (The Eight) and Skupina výtvarných umělců (Group of Fine Artists) playing key roles in promoting avant-garde art.

The provided snippets also mention Josefa Čapková and Archibald Pennington as artists who inspired him. While Josefa Čapková is less prominent in standard art historical accounts than her male counterpart Josef Čapek, her inclusion suggests a specific personal influence or a figure deserving of further research. Archibald Pennington is an even more obscure name in this context, possibly indicating a lesser-known international artist or a more personal connection. Král's work, with its blend of romantic color contrasts and sculptural forms, synthesized these diverse influences into a coherent and personal vision.

Final Works and Tragic End

The final years of Jaroslav Král's life were lived under the duress of Nazi occupation. Despite the oppressive circumstances, he continued to create art that spoke to the anxieties and hopes of his time. His commitment to his art and his implicit critique of the regime ultimately led to his persecution. In 1942, Jaroslav Král was arrested and deported to a concentration camp, where he tragically perished in the same year. His death was a profound loss for Czech art, silencing a unique and evolving voice.

Some sources list works with later dates, such as Senavé ženy (Dreaming Women, 1945) and Žena s dětem na tanečním salónu (Woman with Children in a Dance Hall, 1947). Given his death in 1942, these dates likely refer to works conceived earlier, completed by others based on his sketches, or perhaps posthumously titled and exhibited. These later attributed works often continue to explore themes of peace, domestic life, and social observation, sometimes blending social realism with classical elements, suggesting a direction his art might have taken had his life not been cut short.

Legacy and Enduring Significance

Jaroslav Král's artistic legacy is multifaceted. He is remembered as a key figure of Czech modernism, an artist who skillfully navigated and synthesized various early 20th-century artistic movements to create a deeply personal and expressive body of work. His early adoption of Cubist principles, tempered with a lyrical sensibility, and his later engagement with Neoclassicism and profound humanism, mark him as an artist of considerable range and depth.

His works are characterized by a sophisticated understanding of color and form, a distinctive approach to depicting the human figure—especially women—and an ability to imbue his scenes with a palpable emotional atmosphere. Whether exploring the anxieties of war, the quietude of family life, or the timeless beauty of the human form, Král's art consistently reveals a deep empathy and a keen observational eye.

His paintings are held in various public and private collections, primarily in the Czech Republic, and continue to be studied and appreciated for their artistic merit and historical significance. Exhibitions of his work, sometimes in conjunction with contemporaries like Jan Zrzavý, help to illuminate his contributions and his place within the broader narrative of European modernism. The auction appearance of works like Nu de femme (Female Nude) from 1930 further attests to the ongoing interest in his art.

Jaroslav Král's life and work serve as a poignant reminder of the vital role artists play in reflecting and shaping their times. His journey from the hopeful artistic explorations of the early 20th century to the somber realities of wartime Europe is a story of resilience, creativity, and an unwavering commitment to artistic expression. He remains an important voice, whose art continues to speak to us of the complexities of the human experience, the search for beauty, and the enduring power of the human spirit. His contribution to Czech art, though tragically curtailed, remains indelible.