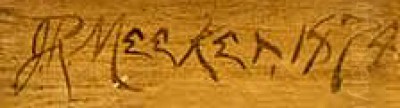

Joseph Rusling Meeker stands as a distinctive figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century American art. While many of his contemporaries looked to the grand vistas of the Hudson River Valley, the Rockies, or Europe, Meeker found his muse in the humid, atmospheric depths of the American South, particularly the swamps and bayous of the Mississippi River Delta. Born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1827, and passing away in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1887, Meeker forged a career that blended careful observation with a deeply romantic sensibility, leaving behind a body of work that captures the unique beauty and mystery of a region often overlooked by the mainstream art world of his time. His paintings, often imbued with a soft, hazy light and a sense of profound stillness, invite viewers into a world both real and imagined, shaped by nature, literature, and personal experience.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Joseph Rusling Meeker's journey into art began not in the South he would become famous for painting, but in the Northeast. After his birth in Newark, his family relocated to Auburn, New York. It was here that his artistic inclinations likely began to take shape. Seeking formal training, Meeker pursued studies that eventually led him to the National Academy of Design in New York City, a crucial institution for aspiring artists in mid-nineteenth-century America. A pivotal moment in his education was his tutelage under Asher B. Durand (1796-1886), one of the foundational figures of the Hudson River School.

Durand, known for his meticulous attention to detail and his philosophy of painting directly from nature, undoubtedly imparted valuable technical skills to Meeker. The Hudson River School, pioneered by artists like Thomas Cole (1801-1848) and continued by Durand, Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900), and Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902), emphasized the depiction of American landscapes as both a realistic representation and a reflection of divine presence or national identity. Meeker's early work reflects this influence, showing a commitment to accurate rendering and an appreciation for the grandeur of the natural world. However, even in these formative years, hints of a more personal, atmospheric style began to emerge, suggesting a path diverging from the sometimes crisp, detailed panoramas favored by the school's leading lights.

The Crucible of War: Discovering the Bayou

A defining chapter in Meeker's life and artistic development was his service during the American Civil War. Unlike artists who served as illustrators on the front lines, Meeker held the position of a paymaster for the Union Navy, assigned to a gunboat patrolling the Mississippi River and its tributaries. This role, while perhaps less overtly dangerous than direct combat, provided him with an unparalleled opportunity for intimate, sustained observation of the Southern landscape under unique circumstances. He spent considerable time navigating the intricate network of swamps, bayous, and waterways that characterize the Mississippi Delta.

This immersion was transformative. The landscapes he encountered were vastly different from the rolling hills and clear light of the Northeast. He witnessed firsthand the dense vegetation, the towering cypress trees draped in Spanish moss, the reflective, often murky waters, and the pervasive humidity that softened edges and created a unique atmospheric haze. These experiences provided him with a wealth of sketches and, more importantly, deeply ingrained visual and emotional memories. The somber beauty, the stillness, the sense of isolation, and perhaps even the underlying tension of the war-torn region seeped into his artistic consciousness. This direct, prolonged contact with the bayou environment became the bedrock upon which he would build his mature artistic identity, providing authentic source material that set his work apart.

St. Louis: An Artistic Hub in the Midwest

Following the conclusion of the Civil War, Joseph Rusling Meeker chose not to return to the established art centers of the East Coast but instead settled in St. Louis, Missouri, around 1859, making it his permanent home. At the time, St. Louis was a burgeoning metropolis, a vital hub connecting the East and the expanding West, and it possessed a growing cultural scene. Meeker quickly became a prominent figure within this environment, contributing significantly to its artistic life.

He was more than just a painter; Meeker actively engaged with the local art community as a teacher, an art critic for local publications, and an organizer. He was instrumental in the activities of groups like the St. Louis Art Association and the St. Louis Sketch Club, platforms where artists could exhibit work, exchange ideas, and foster a sense of community. His leadership helped elevate the status of the arts in the city. While St. Louis had other notable artists associated with it, such as George Caleb Bingham (1811-1879), known for his depictions of frontier life, or later, figures like Carl Wimar (1828-1862) who focused on Native American subjects and the West, Meeker carved out his niche with his specialized focus on the Southern landscape, bringing a different flavor to the regional art scene. His studio became a known entity, and his works were regularly featured in local and regional exhibitions, gaining recognition and patronage.

The Evolution of Style: From Realism to Romanticism

Meeker's artistic style underwent a noticeable evolution throughout his career, though it remained anchored in landscape painting. His early training with Asher B. Durand grounded him in the Hudson River School's emphasis on detailed observation and fidelity to nature. Some of his earlier works exhibit this precision, capturing the specific forms of trees, water, and land with clarity. However, his experiences in the South and his own temperament pushed him towards a more Romantic interpretation of the landscape.

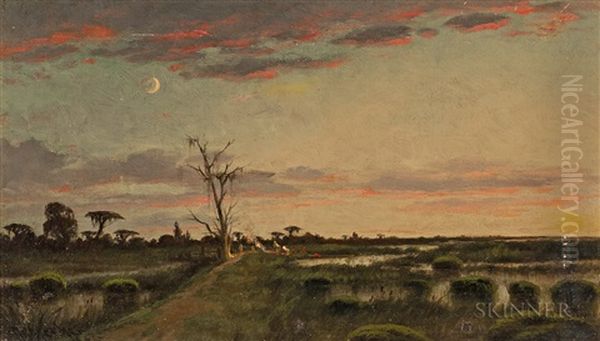

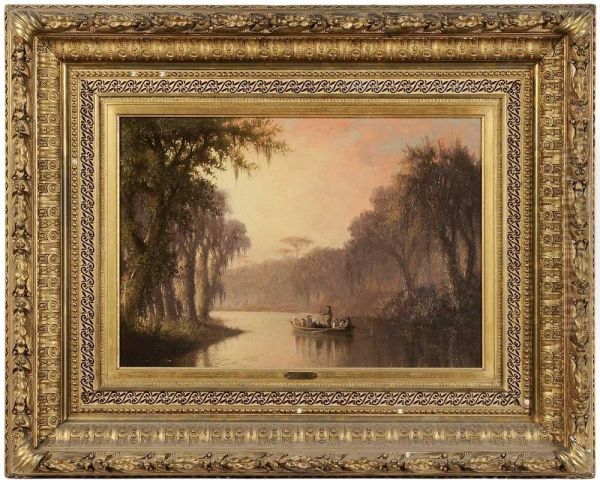

The raw, often untamed nature of the bayou seemed to demand a different approach than the picturesque hills of the Catskills. Meeker increasingly focused on mood, atmosphere, and the emotional resonance of the scene. His brushwork, while still capable of rendering detail, often became softer, more suggestive, particularly in his handling of foliage and water reflections. He developed a fascination with the effects of light – the hazy glow of dawn, the fiery colors of sunset, the ethereal quality of moonlight filtering through mist and Spanish moss. This shift moved his work away from pure topographical representation towards a more poetic and evocative portrayal of place, emphasizing the mystery and sometimes melancholic beauty he perceived in the Southern wetlands.

Luminism and the Bayou Atmosphere

A key characteristic of Meeker's mature style is its strong affinity with Luminism, a mid-19th-century American landscape painting style characterized by its treatment of light and atmosphere. Luminist painters, such as Fitz Henry Lane (1804-1865), Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904), John Frederick Kensett (1816-1872), and Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823-1880), often depicted calm, reflective water, expansive skies, and meticulously rendered effects of light, typically using concealed brushwork to create smooth, polished surfaces. Their works often evoke a sense of quiet contemplation and transcendental stillness.

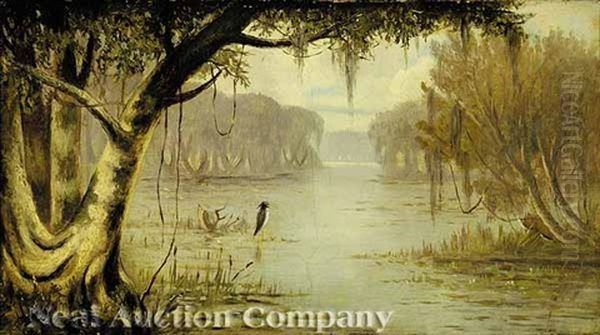

Meeker adapted Luminist principles to the unique conditions of the bayou. While the classic Luminist scenes often feature the clear, crisp light of the New England coast or the Hudson River, Meeker captured the diffused, humid light of the South. He masterfully used subtle gradations of tone and color to depict the hazy air, the reflections on still water, and the interplay of light and shadow within the dense swamps. His skies are often soft and glowing, contributing to the dreamlike, almost mystical quality of his paintings. This "bayou Luminism" is a distinctive aspect of his work, setting him apart from both his Hudson River School predecessors and his East Coast Luminist contemporaries. Some art historians also note a possible awareness of the atmospheric effects achieved by European masters like Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) or the dramatic light in the works of J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), although Meeker’s interpretation remained distinctly American and deeply tied to his chosen subject matter.

Themes and Subjects: The Allure of the Swamp

The dominant subject throughout Meeker's mature career was the landscape of the Mississippi River Delta – its swamps, bayous, and rivers. He was captivated by the unique ecosystem: the cypress trees with their distinctive "knees," the pervasive Spanish moss hanging like natural drapery, the slow-moving, reflective waters, and the abundant, often decaying vegetation. He saw not just a wilderness, but a place of profound, albeit unconventional, beauty.

His paintings often convey a sense of stillness and solitude. Human presence, when included, is usually minimal – a small boat, a distant campfire – serving primarily to emphasize the scale and dominance of nature. Meeker explored the bayou at different times of day and under various weather conditions, capturing the subtle shifts in light and mood. Sunrise and sunset were favorite times, allowing him to exploit the dramatic color and soft light characteristic of his Luminist approach. He managed to portray the swamps not as menacing or repellent, but as enchanting, mysterious realms, full of quiet dignity and a unique, melancholic charm. His work offered a counter-narrative to prevailing views of swamps as mere wastelands, revealing their complex ecological and aesthetic character.

Literary Inspiration: The Evangeline Series

Beyond the direct observation of nature, Meeker's work was significantly influenced by literature, most notably Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's epic poem Evangeline, A Tale of Acadie (1847). The poem tells the tragic story of Evangeline Bellefontaine, an Acadian woman separated from her beloved Gabriel Lajeunesse during the British expulsion of the Acadians from Nova Scotia in the mid-18th century. Her long search takes her through various parts of America, including the bayous of Louisiana, where many Acadians (who became known as Cajuns) eventually settled.

Meeker was deeply moved by the poem's themes of loss, endurance, and the search for love amidst displacement, all set against the backdrop of the American landscape, particularly the Louisiana sections. He created a series of paintings directly inspired by Evangeline, often depicting solitary female figures (representing Evangeline) in poignant bayou settings, or simply focusing on the landscapes described in the poem, imbued with its romantic melancholy. Works like The Land of Evangeline (1874) and The Acadians in the Achafalaya, "Evangeline" (1871) explicitly reference the poem. The recurring motif of ancient, moss-draped live oaks in his work, symbols of endurance and the passage of time, resonates strongly with the poem's narrative and the historical experience of the Acadians. This literary dimension added another layer of meaning and emotional depth to his landscapes, connecting them to broader cultural narratives of history and romance. Some have even suggested a resonance between his solitary, enduring trees and the imagery found in the poetry of Walt Whitman (1819-1892), another contemporary exploring American identity and nature.

Representative Works: Capturing the Bayou's Soul

Several paintings stand out as exemplary of Joseph Rusling Meeker's style and thematic concerns.

The Land of Evangeline (1874): This painting, directly referencing Longfellow's poem, likely depicts the Louisiana bayou landscape through which the poem's heroine searches. It would typically feature the key elements of Meeker's style: moss-draped trees, still water reflecting a soft sky, and an overall atmosphere of romantic melancholy and timelessness. The landscape itself becomes a character, echoing the themes of endurance and sorrow found in the poem.

The Acadians in the Achafalaya, "Evangeline" (1871): Another work tied to the poem, this piece likely focuses on the Atchafalaya Basin, a significant location in the Evangeline narrative and a real area of Louisiana known for its vast swamps. Meeker would use his intimate knowledge of such environments to create a scene that is both geographically recognizable and emotionally resonant with the story of the exiled Acadians finding refuge.

Day on the Yazoo (1885): This later work, depicting a scene on the Yazoo River (a tributary of the Mississippi), showcases Meeker's mature style. It likely captures the soft light of early morning or late afternoon, a favorite time for the artist. The painting would emphasize the atmospheric effects of the humid Southern air, the reflections on the water, and the lush, perhaps slightly wild, vegetation along the riverbanks. It represents his continued dedication to capturing the specific character of Southern waterways.

Bayou Field with Campsite at Dusk under a Crescent Moon (1885): This evocative title suggests a quintessential Meeker scene. The combination of dusk, a crescent moon, and a small campsite points to themes of solitude, the transition between day and night, and the quiet mystery of the bayou after dark. The Luminist handling of the fading light and the emerging moonlight on the water and landscape would be central to the painting's mood.

These works, along with others like Louisiana Bayou Scene and Sunset on the Mississippi, consistently demonstrate Meeker's unique ability to blend realistic observation of the Southern landscape with a deeply felt romantic and atmospheric sensibility, often enhanced by literary or historical associations.

Meeker's Place in American Art

Joseph Rusling Meeker occupies a specific and important place within the broader context of 19th-century American art. While trained in the Hudson River School tradition under Durand, he moved beyond its typical subjects and, to some extent, its stylistic conventions. His focus on the Mississippi Delta distinguished him from contemporaries like Church or Bierstadt, who sought the monumental and sublime in South America, the Arctic, or the American West. Meeker found his sublime in the intimate, humid, and often overlooked landscapes of the South.

His connection to Luminism links him to artists like Lane, Heade, Kensett, and Gifford, yet his application of Luminist techniques to the bayou environment gives his work a unique regional inflection. He was less concerned with the crisp, crystalline light often found in New England coastal scenes and more interested in capturing the diffused, moisture-laden atmosphere of the swamps. Furthermore, his explicit engagement with literary themes, particularly the Evangeline story, adds a narrative and emotional dimension not always present in purely observational landscape painting. He successfully synthesized direct observation gained during his wartime service, a romantic temperament, Luminist techniques, and literary inspiration to create a cohesive and personal body of work.

Legacy and Collections

Joseph Rusling Meeker's contributions to American art were recognized during his lifetime, particularly in St. Louis, where he was a respected figure. After his death in 1887, his work continued to be appreciated, although perhaps overshadowed at times by the grander narratives of the Hudson River School or the later advent of Impressionism and Modernism. However, in recent decades, there has been renewed interest in regional American art and in styles like Luminism, leading to a greater appreciation of Meeker's unique vision.

His paintings are held in the permanent collections of several important American museums, ensuring his legacy endures. Notable institutions include the Saint Louis Art Museum, which holds a significant representation of his work given his connection to the city; the New Orleans Museum of Art, appropriately located in the heart of the region he depicted; the Brooklyn Museum in New York; and the Mississippi Museum of Art. The presence of his work in these collections allows contemporary audiences to experience his evocative portrayals of the Southern landscape and acknowledges his role as a significant interpreter of a specific American environment.

Market Reception and Valuation

The art market reflects the sustained interest in Joseph Rusling Meeker's work. His paintings appear periodically at auction and are sought after by collectors of 19th-century American art, particularly those interested in Southern subjects or Luminist landscapes. Prices for his oil paintings generally range from the mid-thousands to tens of thousands of dollars, depending on the size, quality, subject matter, and condition of the work.

For instance, auction records show sales like Louisiana Bayou Scene achieving $14,687, and Bayou Field with Campsite at Dusk under a Crescent Moon selling for $22,325, near its high estimate. While perhaps not reaching the astronomical figures of some of his Hudson River School contemporaries like Church or Bierstadt, these prices indicate a solid and appreciative market for Meeker's distinctive paintings. This market valuation underscores his recognized status as an important historical artist who captured a unique aspect of the American experience and landscape with skill and sensitivity.

Conclusion: The Enduring Vision of the Bayou Painter

Joseph Rusling Meeker carved a unique path in American art. Shaped by his training under Asher B. Durand, transformed by his Civil War experiences in the Mississippi Delta, and inspired by both the natural world and romantic literature, he became the preeminent painter of the Louisiana bayou in the 19th century. His adaptation of Luminist principles to capture the humid, mysterious atmosphere of the swamps resulted in a body of work that is both visually captivating and emotionally resonant.

Through his evocative landscapes, often imbued with a sense of quiet melancholy and profound stillness, Meeker invited viewers to see the beauty and mystery in a landscape often misunderstood or overlooked. His dedication to this specific region, combined with his skillful handling of light and atmosphere, secured his place as a significant regionalist painter with a national importance. As a leader in the St. Louis art community and the creator of enduring images like those inspired by Evangeline, Joseph Rusling Meeker left a legacy that continues to enchant and inform, offering a timeless glimpse into the soul of the American South.