An Introduction to an Italian-American Visionary

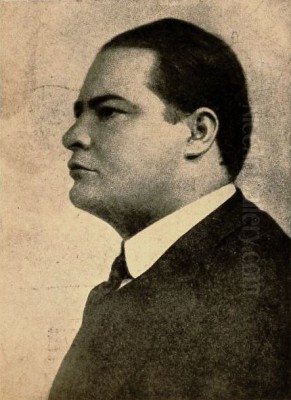

Joseph Stella stands as a pivotal figure in the narrative of American Modernism, an artist whose life and work bridged the cultural landscapes of his native Italy and his adopted home, the United States. Born Giuseppe Michele Stella in Muro Lucano, Italy, in 1877, he emigrated to New York City in 1896, initially pursuing studies in medicine and pharmacology before dedicating himself entirely to art. His journey reflects a profound engagement with the rapidly changing world of the early 20th century, capturing the dynamism of industrial America while retaining a deep connection to European artistic traditions and the spiritual power of nature. Stella is perhaps most celebrated for his iconic depictions of the Brooklyn Bridge, works that encapsulate the energy and awe of the modern metropolis, but his artistic output was remarkably diverse, encompassing gritty urban realism, vibrant Futurist compositions, precise industrial landscapes, and lush, symbolic explorations of the natural world. His unique synthesis of European avant-garde styles with distinctly American subjects secured his place as a leading voice in the development of modern art in the United States. He died in Queens, New York, in 1946, leaving behind a rich and complex body of work that continues to fascinate and inspire.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Stella's artistic inclinations emerged after his arrival in New York. Forsaking his initial medical studies, he enrolled at the Art Students League in 1897, a crucial step that set him on his lifelong path. There, he studied under the influential American Impressionist painter William Merritt Chase. Chase, known for his bravura brushwork and keen eye for light and color, provided Stella with a solid academic foundation. However, Stella's early independent work diverged significantly from the genteel subjects often favored by Chase. Instead, Stella turned his attention to the raw, often harsh realities of immigrant life in New York City's poorer neighborhoods, particularly the Lower East Side.

During this formative period, Stella worked as an illustrator, contributing drawings to magazines such as The Outlook, Charities and the Common, and later The Survey. His illustrations from this time, often executed in a dark, realist style, documented the lives of miners, immigrants, and the urban poor with empathy and a sharp observational eye. These early works share thematic concerns with the artists of the Ashcan School, such as Robert Henri, John Sloan, and George Luks, who also focused on depicting the unvarnished aspects of city life. However, Stella's approach often retained a more formal, draftsman-like quality compared to the looser, more painterly style characteristic of the Ashcan painters. This early focus on social realism provided a grounding in observation that would inform his later, more abstract explorations.

The European Catalyst: Immersion in Modernism

A critical turning point in Stella's artistic development came with his return trip to Europe, which lasted from 1909 to 1912. He spent significant time in Italy and Paris, immersing himself in the continent's rich artistic heritage and its burgeoning avant-garde movements. In Italy, he reconnected with the art of the Renaissance masters, particularly the Venetian school's emphasis on color and light, perhaps finding inspiration in the works of artists like Titian or Tintoretto. This exposure to classical traditions provided a historical depth that would subtly resonate even in his most modern works.

His time in Paris, however, proved truly transformative. The French capital was the epicenter of artistic innovation, and Stella readily absorbed the radical ideas circulating there. He encountered Fauvism, with its bold, non-naturalistic use of color, championed by artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain. He also engaged deeply with Cubism, the revolutionary style developed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, which fragmented objects and depicted them from multiple viewpoints simultaneously. This exposure fundamentally altered his perception of form and space.

Crucially, Stella connected with key figures of the European avant-garde. He frequented the Parisian salon of Gertrude Stein, a vital hub for artists and writers. There, and elsewhere in Paris, he met leading Italian Futurist artists, including Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, and Gino Severini. He also began a friendship with Marcel Duchamp, whose intellectual and conceptual approach to art would later resonate with Stella's own experimental tendencies. This period of intense study and interaction provided Stella with the tools and inspiration to forge his own modern artistic language upon his return to America. Works like Pointillist Procession (c. 1911-12) show his direct engagement with European Post-Impressionist techniques during this vital period.

Futurism and the American Experience

Returning to New York in 1912, Stella was armed with a new artistic vocabulary, ready to interpret the American experience through the lens of European Modernism. The timing was perfect, as the American art scene was on the cusp of a major transformation, catalyzed by the groundbreaking International Exhibition of Modern Art, better known as the Armory Show, held in 1913. Stella participated in this landmark exhibition, which introduced American audiences on a large scale to the radical developments in European art, including Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism.

Stella quickly became one of the foremost proponents of Futurism in America. This Italian movement celebrated dynamism, speed, technology, and the machine age. Stella found the perfect subject matter in the vibrant, chaotic energy of New York City. His early Futurist works, such as Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras (1913-14), capture the dazzling, cacophonous atmosphere of the amusement park at night, using fragmented forms, kaleidoscopic colors, and radiating lines of force to convey sensory overload and excitement. This work, exhibited at the Montross Gallery in 1914, established him as a significant modern voice.

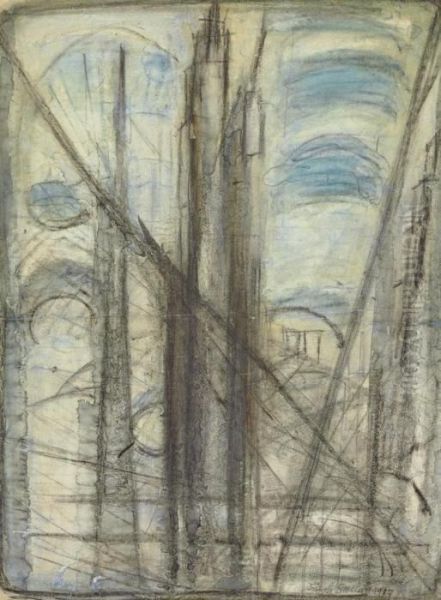

His engagement with Futurism culminated in his most famous series of works depicting the Brooklyn Bridge. The first major painting, Brooklyn Bridge (1919-20), now at the Yale University Art Gallery, and the later monumental five-panel version, The Bridge (1920-22), housed at the Newark Museum, are considered masterpieces of American modern art. These paintings transform the bridge into a quasi-religious icon of the modern age, a cathedral of steel and cable. Stella employed Futurist principles—dynamic lines, fractured perspectives, vibrant color suggesting electric light—to convey the immense scale, power, and spiritual awe inspired by this engineering marvel. He saw the bridge as a symbol of America's industrial might and the unifying spirit of modern life, a shrine containing "all the efforts of the new civilization of AMERICA."

Precisionism and the Urban Landscape

While deeply influenced by Futurism's dynamism, Stella's work, particularly from the late 1910s through the 1920s, also aligned closely with the emerging American style known as Precisionism. Though not a formal movement with a manifesto, Precisionism was characterized by a focus on industrial and urban subjects, rendered with sharp focus, clean lines, geometric simplification, and smooth surfaces, largely devoid of human figures. Stella's depictions of factories, skyscrapers, and structures like the Brooklyn Bridge shared this aesthetic.

Unlike the explosive energy of some of his purely Futurist works, Stella's Precisionist-inflected paintings often emphasize the underlying geometric structure and monumental stability of modern architecture and industry. The soaring cables and Gothic arches of the Brooklyn Bridge, for instance, are rendered with a clarity and linearity that highlights their architectural form as much as their dynamic energy. This approach connected his work to that of other key Precisionist artists like Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth, who similarly found beauty and order in the forms of American industry – grain elevators, factories, and cityscapes. Stella's contribution was unique in its fusion of this precise rendering with lingering Futurist elements and a more overt sense of emotional or spiritual grandeur, particularly evident in the dramatic lighting and cathedral-like compositions of his bridge paintings.

Exploring Nature and Symbolism

Despite his fame as a painter of the modern industrial city, a significant portion of Joseph Stella's oeuvre reveals a profound and enduring fascination with the natural world. Beginning in the late 1910s and continuing throughout his career, he produced numerous works depicting flowers, plants, birds, and landscapes, often imbued with intense color and symbolic meaning. This aspect of his work showcases a different facet of his artistic personality – one rooted in lyricism, spirituality, and a deep connection to his Italian heritage.

His nature paintings range from detailed botanical studies to highly imaginative and symbolic compositions. Works like Tree of My Life (1919) possess a mystical quality, blending observed natural forms with dreamlike imagery. He was particularly drawn to flowers, rendering them with vibrant, almost electric colors and intricate detail, as seen in works like Flowers, Italy (c. 1930) or American Landscape (1929), where industrial elements might subtly coexist with lush vegetation. His frequent visits to the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx provided direct inspiration for many of these works.

In these nature-based paintings, Stella often employed a heightened realism combined with decorative stylization, sometimes bordering on the surreal. The intensity of color and the often oversized, commanding presence of the flora and fauna suggest a spiritual significance attributed to the natural world. This approach distinguishes his work from the more objective or purely abstract nature studies of contemporaries like Georgia O'Keeffe, though both artists shared an interest in finding powerful forms in nature. Stella's later works, such as The Swan (c. 1924) or Pomegranate, often carry complex symbolic weight, drawing on personal memories, religious iconography, and a pantheistic reverence for life. Some art historians see parallels with the Symbolist movement, perhaps recalling the mystical nature studies of an artist like Odilon Redon.

Religious Themes and Mystical Visions

Stella's Italian Catholic upbringing and his deep engagement with Renaissance and Baroque art also manifested in explicitly religious and mystical themes within his work. While his Brooklyn Bridge paintings have often been interpreted as secular cathedrals, Stella also created works that directly addressed traditional religious subjects, albeit through his unique modernist lens. These works often blend his vibrant color palette and stylized forms with a sense of spiritual intensity and visionary experience.

Paintings like The Virgin (1926) and The Apotheosis of the Rose (1926) exemplify this aspect of his art. They are characterized by rich, jewel-like colors, symmetrical compositions reminiscent of altarpieces, and a profusion of symbolic imagery, often incorporating floral motifs alongside religious figures. Madonna's Effulgence is another example where traditional iconography is transformed through Stella's distinctive style, emphasizing light, color, and decorative patterns to convey a sense of divine radiance and mystery. These works suggest a desire to reconcile his modernist sensibilities with a deeper spiritual searching, finding continuity between the devotional art of the past and his contemporary artistic explorations. This spiritual dimension adds another layer of complexity to Stella's artistic identity, positioning him not just as an observer of the modern world but also as a seeker of transcendent meaning.

Diverse Techniques and Experimentation

Joseph Stella was a versatile artist, proficient not only in oil painting but also in various other media, constantly experimenting with techniques and materials throughout his career. His drawings, often executed in silverpoint or graphite, reveal his exceptional draftsmanship, a skill honed during his early realist phase. His silverpoint drawings, in particular, connect him to the tradition of Renaissance masters like Leonardo da Vinci or Albrecht Dürer, who favored the medium for its precision and delicate tonal qualities. Stella applied this meticulous technique to studies of plants, figures, and urban details.

In the 1920s, influenced perhaps by the Dada movement and his friendship with Marcel Duchamp, Stella embraced collage. He created intricate works by assembling discarded scraps of paper, wrappers, and other ephemera found on the city streets. These collages, sometimes referred to as "Natura Morta" (Still Life) or described by Stella as akin to "nature machines," juxtapose fragments of urban detritus with organic forms, reflecting his ongoing dialogue between the industrial and natural worlds. This engagement with collage links him to European Dada artists like Kurt Schwitters, who also used found materials to create evocative compositions.

Stella also experimented with reverse painting on glass, a technique also explored by Duchamp. This demanding process involves painting directly onto the back of a glass pane, requiring the artist to work in reverse order, applying foreground details first. Stella created several striking floral compositions and abstract designs using this method, achieving a unique luminosity and smoothness of surface inherent to the medium. His willingness to explore diverse media underscores his restless creativity and his commitment to finding the most effective means to express his complex artistic vision.

Relationships, Influence, and Artistic Circles

Joseph Stella navigated the dynamic art worlds of both Europe and America, forging connections with many leading artists and intellectuals of his time. His early training with William Merritt Chase provided a traditional foundation, while his European travels brought him into the orbit of Futurists like Boccioni, Severini, and Carrà, and avant-garde figures like Picasso, Matisse, and Gertrude Stein. His enduring friendship with Marcel Duchamp was particularly significant, reflecting a shared interest in conceptual approaches and technical experimentation, notably with glass.

Upon returning to America, Stella became an active participant in the New York art scene. He associated with fellow modernists and patrons, including those in the circle of photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, although he was not formally part of Stieglitz's group which included artists like Georgia O'Keeffe, Arthur Dove, and Marsden Hartley. Stella was involved in organizing efforts like the Society of Independent Artists, founded in 1916 along democratic, no-jury principles similar to the Salon des Indépendants in Paris, serving alongside figures like Duchamp and Man Ray. He also maintained connections with artists like Albert Gleizes, a prominent Cubist painter who spent time in New York.

Stella's work, while unique, inevitably invites comparison with contemporaries. His early realism echoed the subjects of the Ashcan School (Henri, Sloan, Luks), while his industrial scenes paralleled the work of Precisionists (Sheeler, Demuth). His vibrant floral paintings find some resonance with O'Keeffe's explorations of natural forms, though his approach remained distinct in its symbolic and often more decorative quality. Beyond the visual arts, Stella felt a strong affinity for the American poet Walt Whitman, seeing in Whitman's expansive, democratic vision a parallel to his own efforts to capture the spirit and energy of modern America. Stella saw himself, like Whitman, as a bridge between cultures and experiences.

Legacy and Enduring Significance

Joseph Stella's legacy resides in his powerful and multifaceted contribution to American Modernism. He played a crucial role in introducing and adapting European avant-garde styles, particularly Futurism, to an American context, using them to interpret the unique landscape and energy of the United States in the early 20th century. His depictions of the Brooklyn Bridge remain iconic images of the American machine age, capturing both the technological sublime and a sense of spiritual awe.

Beyond his celebrated industrial scenes, Stella's diverse body of work—ranging from sensitive realist drawings of immigrants to vibrant Futurist cityscapes, precise industrial renderings, experimental collages, and lush, symbolic paintings of nature—reveals an artist of remarkable range and complexity. He successfully navigated the tension between his European heritage and his American experience, between the dynamism of the modern city and the enduring power of the natural world, between objective observation and mystical symbolism.

His work is held in major museum collections across the United States, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Newark Museum, and the Yale University Art Gallery, ensuring its continued visibility and study. Joseph Stella's unique artistic vision, characterized by its synthesis of diverse influences, technical virtuosity, and profound engagement with the themes of modernity, nature, and spirituality, secures his position as a major and enduring figure in the history of American art. His ability to bridge worlds—old and new, industrial and natural, European and American—remains a testament to the richness and complexity of the modernist project.