Preston Dickinson stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of early twentieth-century American modernism. Active during a transformative period in art history, Dickinson forged a distinctive style that synthesized European avant-garde movements with a uniquely American sensibility. His keen eye for industrial architecture, his sophisticated understanding of color and composition, and his tragically short career all contribute to the compelling narrative of an artist who captured the spirit of a rapidly changing nation. Though his life was cut short, his body of work offers a fascinating glimpse into the development of Precisionism and the broader currents of modern art in the United States.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

William Preston Dickinson was born in New York City in 1889 (some sources state 1891, but 1889 is more commonly cited by major institutions). His early life was marked by modest circumstances. His father, a calligrapher, amateur painter, and interior decorator, likely provided an initial exposure to the visual arts, perhaps instilling in the young Dickinson an appreciation for line, form, and design. This familial connection to artistic pursuits, however informal, may have planted the seeds for his future career.

New York City at the turn of the century was a burgeoning metropolis, a hub of industrial growth and cultural ferment. The visual landscape of the city, with its towering new skyscrapers, sprawling factories, and intricate networks of bridges and railways, would later become a profound source of inspiration for Dickinson and his contemporaries. It was in this dynamic environment that Dickinson's artistic sensibilities began to take shape, leading him to seek formal training to hone his nascent talents.

Formal Training: The Art Students League of New York

Recognizing his artistic calling, Dickinson enrolled at the prestigious Art Students League of New York around 1906, studying there until approximately 1910. The League was a vital institution for aspiring American artists, offering a more liberal and progressive alternative to the traditional academic training of the National Academy of Design. Here, students could learn from practicing artists and engage with a variety of artistic philosophies.

During his time at the League, Dickinson had the opportunity to study under several influential instructors. Among them was William Merritt Chase, a renowned American Impressionist and a highly respected teacher. Chase's emphasis on painterly technique, direct observation, and the importance of capturing light and atmosphere would have provided Dickinson with a solid foundation in the fundamentals of painting. Another significant mentor was Ernest Lawson, a member of "The Eight" and a landscape painter known for his lyrical, Impressionistic style. Lawson's approach to color and his ability to imbue urban scenes with a poetic quality may have resonated with Dickinson.

Perhaps one of the most impactful teachers for Dickinson at the League was George Bellows. A leading figure of the Ashcan School, Bellows championed the depiction of everyday urban life, often focusing on the grittier, more dynamic aspects of the city. Bellows' robust style and his commitment to portraying contemporary American reality likely encouraged Dickinson to look to his immediate surroundings for subject matter. The combined influence of these diverse instructors equipped Dickinson with a versatile skill set and a broad understanding of different artistic approaches, preparing him for the next crucial phase of his development.

The Parisian Sojourn: Exposure to European Modernism

Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Preston Dickinson recognized the importance of experiencing European art firsthand, particularly the revolutionary movements unfolding in Paris. Around 1910, with the financial support of art patron Henry Barbey, Dickinson traveled to Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. He remained in Europe until the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

In Paris, Dickinson immersed himself in the vibrant artistic milieu. He continued his formal studies at the École des Beaux-Arts and the Académie Julian, institutions that, while more traditional, still provided rigorous training. More importantly, however, Paris offered him direct exposure to the radical innovations of Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and, most significantly, Cubism. He would have seen the works of Paul Cézanne, whose structural approach to composition and emphasis on underlying geometric forms were profoundly influencing a new generation of artists.

The groundbreaking works of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, the pioneers of Cubism, were transforming the very definition of painting. Their deconstruction of form, multiple perspectives, and muted palettes offered a new way of representing reality. Dickinson also encountered the vibrant colors and expressive freedom of Fauvist painters like Henri Matisse and André Derain. Furthermore, the influence of Japanese woodblock prints (Ukiyo-e), with their flattened perspectives, bold outlines, and asymmetrical compositions, was pervasive in Parisian art circles, and Dickinson, like many of his contemporaries such as Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas before him, absorbed these elements. He exhibited his work at the Salon des Artistes Français and the Salon des Indépendants, gaining recognition in this competitive environment.

This period was crucial for Dickinson. He assimilated these diverse influences, not by direct imitation, but by selectively incorporating elements that resonated with his own evolving vision. The intellectual rigor of Cubism, the structural integrity of Cézanne, and the compositional elegance of Japanese art would all become integral components of his mature style.

Return to America and the Emergence of Precisionism

With the onset of World War I in 1914, Preston Dickinson returned to the United States. He brought back with him a sophisticated understanding of European modernism, which he began to synthesize with American subjects. The 1910s and 1920s were a period of intense artistic experimentation in America, with artists seeking to define a distinctly modern American art. Dickinson quickly became associated with a group of artists who would later be known as Precisionists.

Precisionism, also sometimes referred to as Cubist-Realism or the Immaculates, was not a formal movement with a manifesto but rather a shared tendency among artists like Charles Sheeler, Charles Demuth, Georgia O'Keeffe (in her architectural works), Louis Lozowick, Niles Spencer, and Ralston Crawford. These artists were drawn to the clean lines, geometric forms, and functional beauty of the modern American industrial and urban landscape. They depicted factories, skyscrapers, bridges, and machinery with a smooth, precise, and often sharply defined technique, eschewing visible brushstrokes and emphasizing clarity and order.

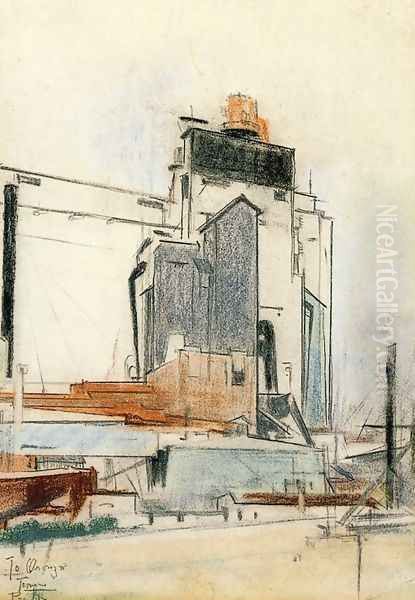

Dickinson's work from this period perfectly embodies the Precisionist ethos. He was captivated by the monumental forms of grain elevators, the intricate networks of factory complexes, and the stark geometry of urban structures. His paintings celebrated the power and ingenuity of American industry, but often with a cool, detached objectivity that highlighted the abstract qualities of these subjects. He found a kind of austere beauty in these man-made landscapes, transforming them into carefully orchestrated compositions of line, plane, and volume.

Key Themes and Subjects in Dickinson's Art

Preston Dickinson's oeuvre, though developed over a relatively short period, explored several recurring themes and subjects, each filtered through his unique modernist lens.

The Industrial Landscape

The most iconic aspect of Dickinson's work is his depiction of the industrial landscape. He was one of the first American artists to consistently find aesthetic merit in factories, smokestacks, grain elevators, and industrial waterfronts. Works like Grain Elevator (Columbus Museum of Art) and Factory (Columbus Museum of Art) showcase his ability to distill these complex structures into powerful geometric compositions. He often employed multiple viewpoints and flattened perspectives, influenced by Cubism, to convey the scale and dynamism of these sites. His industrial scenes are not typically populated by human figures, emphasizing the monumental and almost abstract nature of the structures themselves. He shared this fascination with industrial subjects with contemporaries like Charles Sheeler, who famously photographed and painted the Ford River Rouge Plant, and Louis Lozowick, whose lithographs celebrated the machine age.

Urban Vistas and Architecture

Beyond the factory, Dickinson was also drawn to the broader urban environment. He painted cityscapes, often focusing on the interplay of architectural forms, the patterns of streets, and the unique character of specific locales. His time in Quebec, for instance, resulted in a series of paintings that captured the distinctive architecture and atmosphere of the old city. These works, such as Quebec (Whitney Museum of American Art), demonstrate his ability to apply his modernist principles to different types of architectural subjects, highlighting their geometric underpinnings while also conveying a sense of place. He often used strong diagonals and an elevated viewpoint to create dynamic and engaging compositions, a technique also seen in the urban works of John Marin.

Still Life Compositions

While best known for his industrial and architectural scenes, Preston Dickinson was also a masterful painter of still lifes. These works provided a more intimate arena for his formal experimentation. His still lifes often feature everyday objects – fruit, pitchers, tableware – arranged in complex, carefully balanced compositions. Here, the influence of Cézanne is particularly evident in the way he models form and explores the relationships between objects in space. He also incorporated Cubist devices, such as fragmented planes and shifting perspectives, into his still lifes, creating a dynamic tension between representation and abstraction. These works reveal his sophisticated understanding of color harmonies and his ability to imbue simple objects with a sense of monumentality. Artists like Juan Gris, the Spanish Cubist, were also renowned for their highly structured and intellectually conceived still lifes, and Dickinson's work in this genre shows a similar concern for formal order.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Influences

Preston Dickinson's artistic style is characterized by its synthesis of various modernist influences, all adapted to his personal vision and applied primarily to American subjects.

Cézannian Structure and Cubist Geometry

The foundational influence of Paul Cézanne is palpable in Dickinson's work. Cézanne's method of building form through planes of color, his emphasis on the underlying geometric structure of objects, and his technique of "passage" (where planes blend into one another) are all echoed in Dickinson's paintings. This structural approach is then further developed through the lens of Cubism. While Dickinson rarely pushed into the full abstraction of Picasso or Braque, he adopted Cubist principles of geometric simplification, the fracturing of form (albeit more subtly), and the use of multiple or ambiguous viewpoints. This allowed him to convey the complexity and dynamism of his subjects, particularly the intricate forms of industrial architecture.

Futurist Dynamism and the Machine Aesthetic

Although not a Futurist in the Italian sense (like Umberto Boccioni or Giacomo Balla, who celebrated speed and violence), Dickinson's work shares with Futurism an interest in the machine aesthetic and the dynamism of the modern industrial world. His paintings often convey a sense of energy and power, reflecting the transformative impact of industrialization. The clean lines, hard edges, and interlocking forms in his industrial scenes can be seen as an American interpretation of the machine age's visual language.

Influence of Japanese Art

The impact of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints, which had so captivated Impressionists and Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, is also discernible in Dickinson's compositions. This influence is seen in his use of flattened perspectives, strong diagonal lines, cropped compositions, and an emphasis on pattern and silhouette. These elements contributed to the decorative quality and formal elegance of his work, providing a counterpoint to the sometimes stark subject matter.

Color and Light

Dickinson possessed a sophisticated sense of color. His palette could range from muted, almost monochromatic tones in some industrial scenes to vibrant, rich hues in his still lifes and Quebec landscapes. He understood how color could define form, create mood, and articulate space. His handling of light was often subtle, focusing more on the interplay of planes and volumes than on dramatic chiaroscuro. However, he could effectively use light and shadow to emphasize the geometric clarity of his subjects and to create a sense of depth and atmosphere. His approach to color sometimes shows an affinity with the Orphist explorations of Robert Delaunay, particularly in the way color itself could become a structural element.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several key works exemplify Preston Dickinson's artistic achievements and stylistic characteristics.

Grain Elevator (c. 1924, Columbus Museum of Art): This painting is a quintessential example of Dickinson's Precisionist style. The towering grain elevator is rendered with clean lines and simplified geometric forms. The composition is dynamic, with strong diagonals and a sense of monumental scale. The color palette is relatively subdued, emphasizing the stark, functional beauty of the industrial structure. It shares a thematic kinship with Charles Demuth's iconic My Egypt, which also depicts grain elevators with a similar sense of reverence and geometric precision.

Factory (c. 1920, Columbus Museum of Art): Another powerful industrial scene, Factory showcases Dickinson's ability to organize complex architectural elements into a cohesive and visually compelling composition. Smokestacks, buildings, and pipes interlock in a rhythmic arrangement of shapes and volumes. The painting captures the imposing presence of the modern factory, a symbol of American industrial might.

Quebec (c. 1925-27, Whitney Museum of American Art): This work demonstrates Dickinson's versatility in applying his modernist vision to a different type of subject. The historic architecture of Quebec City is depicted with an emphasis on its geometric forms and picturesque qualities. The use of vibrant color and a slightly elevated perspective creates a lively and engaging scene, showcasing his ability to capture the unique character of a place.

Still Life with Yellow-Green Chair (c. 1928, The Phillips Collection): This painting highlights Dickinson's mastery of the still life genre. The objects are arranged in a complex, almost Cubist-inspired composition, with shifting planes and ambiguous spatial relationships. The bold use of color, particularly the vibrant yellow-green of the chair, adds a dynamic element to the work. It demonstrates his ability to find formal complexity and visual excitement in everyday objects, much like his European contemporary Juan Gris.

Peter Cooper's Mills (Harlem River) (c. 1921): This work, depicting an industrial site, again shows his fascination with the geometric forms of factories and their surrounding infrastructure. The interplay of buildings, smokestacks, and the river creates a dynamic composition, rendered with his characteristic precision and clarity.

Travels, Later Years, and Untimely Death

Throughout his career, Dickinson traveled, seeking new subjects and, at times, more affordable living conditions. He spent time in Omaha, Nebraska, where he likely encountered the grain elevators that became a recurring motif in his work. His trips to Quebec, Canada, in the mid-1920s resulted in a significant series of landscapes and architectural studies that were well-received.

In the late 1920s, Dickinson, like many artists, faced economic challenges. He reportedly moved to Spain in 1930, perhaps seeking a lower cost of living and new artistic inspiration. Tragically, his time there was brief. Preston Dickinson died of pneumonia in Irun, Spain, in November 1930, at the young age of 41 (or 39, depending on the birth year used). His premature death cut short a promising career, leaving the art world to speculate on what further contributions he might have made.

Dickinson and His Contemporaries

Preston Dickinson was part of a vibrant generation of American artists grappling with modernism. He shared the Precisionist sensibility with Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth, who were perhaps the most prominent figures of that tendency. Sheeler, also a photographer, brought a photographic clarity to his paintings of industrial subjects. Demuth, known for his delicate watercolors and later his "poster portraits," also created iconic images of industrial architecture. Georgia O'Keeffe, while primarily known for her flower paintings and Southwestern landscapes, produced a series of New York skyscraper paintings in the 1920s that share Precisionism's clean lines and geometric abstraction.

While the Precisionists often focused on similar subjects, their individual styles varied. Dickinson's work, for instance, often retained a more painterly quality and a richer color palette compared to the sometimes cooler, more detached approach of Sheeler. He was less inclined towards the overt symbolism found in some of Demuth's work.

Beyond the core Precisionists, Dickinson's work can be seen in the broader context of American modernism, alongside artists like Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, and John Marin, who were associated with Alfred Stieglitz's 291 gallery. While Dickinson was not part of the Stieglitz circle, he shared their commitment to forging a modern American art. His European experiences also connect him to the international currents of modernism, influenced by figures like Cézanne, Picasso, and Matisse, whose impact was felt across the Atlantic.

Legacy and Critical Reception

Despite his relatively short career, Preston Dickinson made a significant contribution to American art. He was one of the pioneering figures of Precisionism, helping to define a style that celebrated the modern American landscape of industry and technology. His work was exhibited regularly during his lifetime at important venues like the Daniel Gallery in New York, which also represented other modernists like Man Ray and Yasuo Kuniyoshi.

After his death, Dickinson's work fell into relative obscurity for a time, overshadowed by some of his more famous contemporaries. However, with the resurgence of interest in early American modernism and Precisionism in the latter half of the twentieth century, his contributions have been re-evaluated and increasingly appreciated. His paintings are now held in the collections of major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Phillips Collection, the Columbus Museum of Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Art historians recognize Dickinson for his sophisticated synthesis of European avant-garde principles with American subject matter. He is praised for his strong compositional skills, his nuanced use of color, and his ability to find aesthetic beauty in the often-overlooked forms of industrial architecture. His work serves as an important bridge between European modernism and the development of a distinctly American artistic voice.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

Preston Dickinson's art offers a compelling vision of early twentieth-century America, a nation undergoing rapid industrialization and urbanization. He approached these modern subjects with an artist's eye, transforming them into ordered, harmonious compositions that highlighted their underlying geometric beauty. Influenced by Cézanne, Cubism, and Japanese art, he forged a personal style that was both sophisticated and accessible. Though his life was tragically brief, Preston Dickinson left behind a body of work that secures his place as a key figure in the Precisionist movement and an important contributor to the rich tapestry of American modernism. His paintings continue to resonate today, offering a timeless meditation on form, industry, and the changing American scene.