Jules Adler, a name that resonates with the poignant depiction of late 19th and early 20th-century French social realities, stands as a significant figure in the Naturalist art movement. His canvases are not merely aesthetic objects but profound social documents, capturing the struggles, dignities, and fleeting moments of joy of the working class and marginalized communities. Known affectionately and aptly as "le peintre des humbles" (the painter of the humble), Adler dedicated his artistic vision to those often overlooked by the grand narratives of art history, creating a body of work that remains both historically vital and deeply human.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

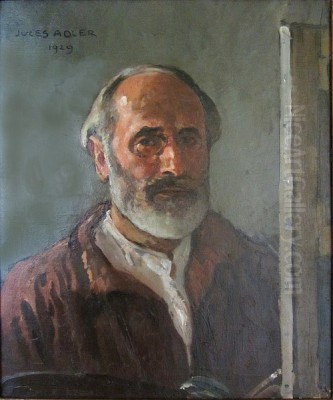

Born on July 8, 1865, in Luxeuil-les-Bains, a town in the Franche-Comté region of eastern France, Jules Adler's origins were modest. His family, of Alsatian Jewish descent, instilled in him a sense of community and perhaps an early awareness of the complexities of identity and belonging, particularly in a France still grappling with the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War and the loss of Alsace-Lorraine. From a young age, Adler exhibited a precocious talent for drawing, a passion that would define his life's trajectory.

Recognizing his potential, his family supported his artistic aspirations. In 1882, at the age of seventeen, he moved to Paris, the undisputed epicenter of the art world. This move was crucial, immersing him in an environment teeming with artistic innovation and intellectual ferment. He initially enrolled at the École Nationale des Arts Décoratifs, a practical choice that provided a solid foundation in design and draughtsmanship. However, his ambitions lay in fine art painting.

Subsequently, in 1884, Adler joined the Académie Julian, a renowned private art school that served as an alternative to the more rigid, official École des Beaux-Arts. The Académie Julian was a crucible for many aspiring artists, both French and international, offering a liberal environment where students could study under established masters. Here, Adler honed his skills under the tutelage of painters like Tony Robert-Fleury, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, and Gustave Boulanger. While these instructors were largely academic painters, the Académie Julian also exposed students to a wider range of artistic currents. He also studied under Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, a prominent Naturalist painter, whose influence would be significant. In 1886, demonstrating his academic proficiency, Adler successfully passed the examination to become an art teacher, a qualification that offered a degree of financial security.

The Emergence of a Naturalist Voice

Adler's artistic career began to take shape in the late 1880s, a period when Naturalism, an extension of Realism, was a dominant force in French art and literature. Naturalism sought to depict life with scientific objectivity, often focusing on the harsher aspects of contemporary existence, the lives of the working class, and the impact of industrialization and urbanization. Influenced by writers like Émile Zola, whose novels vividly portrayed the struggles of ordinary people, Adler found his true calling in depicting the unvarnished realities of the world around him.

He was not alone in this pursuit. Artists like Jean-François Millet had earlier paved the way with his dignified portrayals of peasant life. Gustave Courbet, the standard-bearer of Realism, had championed the depiction of everyday subjects on a grand scale. Adler's contemporaries, such as Léon-Augustin Lhermitte and Alfred Roll, also explored similar themes of labor and rural life. However, Adler brought his own unique sensitivity and profound empathy to these subjects.

His early works began to attract attention at the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. He made his Salon debut in 1888. His commitment to depicting the "humble" was evident from the outset. He was drawn to the streets of Paris, the factories, the mines, and the rural landscapes where ordinary people toiled. His paintings were characterized by their sober palettes, often dominated by grays, browns, and muted earth tones, which underscored the somber realities of his subjects' lives. His brushwork was direct and unembellished, focusing on capturing the essential character and emotional state of the individuals he portrayed.

"Le Peintre des Humbles": Themes and Subjects

The moniker "le peintre des humbles" was not merely a label but an accurate reflection of Adler's artistic and social commitments. He immersed himself in the lives of his subjects, spending time in working-class neighborhoods, observing laborers, and documenting their conditions. His paintings are populated by miners, factory workers, laundresses, street vendors, weary travelers, and impoverished families.

Adler's approach was one of profound empathy rather than detached observation. He did not romanticize poverty, nor did he sensationalize suffering. Instead, he sought to convey the inherent dignity and resilience of individuals facing hardship. His figures are often depicted with a quiet stoicism, their faces etched with the marks of labor and worry, yet imbued with a sense of humanity that transcends their circumstances.

One of his recurring themes was labor. He painted scenes of workers in various settings, from the bustling markets of Les Halles to the dark and dangerous coal mines. These works often highlighted the physically demanding nature of their jobs and the toll it took on their bodies. He also depicted moments of camaraderie and solidarity among workers, recognizing the importance of community in their lives. Another significant theme was the plight of the urban poor. Adler captured the crowded tenements, the soup kitchens, and the desolate streets that were home to many Parisians. His paintings offer a stark contrast to the glamorous image of Belle Époque Paris often portrayed by other artists.

Iconic Works: Canvases of Social Conscience

Jules Adler's oeuvre includes several paintings that have become iconic representations of social conditions and working-class life in late 19th and early 20th-century France. These works are powerful testaments to his artistic skill and his deep social conscience.

La Grève au Creusot (The Strike at Le Creusot, 1899): Perhaps Adler's most famous work, The Strike at Le Creusot is a monumental painting depicting a mass of striking workers at the Schneider ironworks in Le Creusot. The painting captures the tension and determination of the strikers, their faces a mixture of anger, hope, and weariness. Adler does not focus on a single hero but portrays the collective power of the crowd, a sea of individuals united in their struggle for better conditions. The composition is dynamic, with the figures surging forward, creating a sense of unstoppable momentum. This painting, exhibited at the Salon of 1900, became an emblem of the labor movement and cemented Adler's reputation as a painter of social struggle. It is now housed in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Pau.

Les Las (The Weary Ones, 1902): This poignant work depicts a group of exhausted laborers, possibly returning home after a long day's work or perhaps unemployed and seeking sustenance. Their slumped postures and somber expressions convey a profound sense of fatigue and despondency. The muted color palette and the stark, almost desolate setting amplify the feeling of hardship. Adler's sympathetic portrayal invites the viewer to contemplate the human cost of industrial labor. This work is a prime example of his ability to capture the psychological state of his subjects.

La Soupe des Pauvres (The Soup of the Poor, 1898, also sometimes dated 1906): This painting depicts a scene in a soup kitchen, a common sight in Paris at the time. Adler focuses on the faces of the individuals waiting for a meager meal – the elderly, women, and children. There is a quiet dignity in their demeanor, despite their evident poverty. The artist's compassionate gaze is evident, highlighting the social inequalities of the era without resorting to sentimentality. The work underscores the daily struggle for survival faced by many.

Transfusion de Sang de Chèvre au Dispensaire de la Villette (Sheep's Blood Transfusion at the Villette Dispensary, 1892): An earlier but significant work, this painting depicts a medical procedure, likely experimental at the time, being performed on a child in a working-class dispensary. It highlights the vulnerability of the poor and their reliance on charitable institutions for healthcare. The scene is rendered with a clinical yet empathetic eye, capturing the anxiety of the mother and the focused intensity of the medical staff. It reflects the Naturalist interest in scientific advancements and their impact on society.

La Mère et l'enfant (Mother and Child, 1897): This tender portrayal of a working-class mother and her child showcases Adler's ability to capture intimate moments of human connection amidst hardship. The bond between mother and child is a universal theme, but Adler grounds it in the specific context of poverty, suggesting the added burdens and anxieties faced by such families.

These representative works, among many others, demonstrate Adler's consistent engagement with the social issues of his time. He used his art as a means of bearing witness, of giving voice to the voiceless, and of challenging the conscience of his audience.

Social and Political Engagement: The Dreyfus Affair and Beyond

Jules Adler was not an artist who remained aloof from the political and social currents of his time. His Jewish heritage and his deep-seated sense of justice led him to become actively involved in one of the most divisive events in modern French history: the Dreyfus Affair.

In 1894, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish artillery officer in the French army, was falsely convicted of treason. The case quickly became a national scandal, polarizing French society into Dreyfusards (those who believed in Dreyfus's innocence and fought for his exoneration) and anti-Dreyfusards (those who upheld the conviction, often fueled by antisemitism and nationalism).

Adler unequivocally sided with the Dreyfusards. He was a signatory to petitions demanding a retrial and actively participated in the movement to clear Dreyfus's name. His Paris studio, located in Montmartre, became a meeting place for fellow Dreyfusards, including prominent intellectuals, writers, and artists. Among them were the writer Bernard Lazare, one of the earliest champions of Dreyfus's innocence, and the artist Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, known for his socially conscious illustrations and posters. Léon Zadoc-Kahn, son of the Grand Rabbi of France and a fervent Dreyfusard, was also part of this circle. This engagement made Adler a target for antisemitic attacks but also solidified his position as an artist deeply committed to social justice. His involvement in the Dreyfus Affair underscored his belief that art could not be separated from life and that artists had a responsibility to engage with the moral and political issues of their day.

His social conscience extended beyond the Dreyfus Affair. He was a founding committee member of the Salon d'Automne in 1903, an exhibition established as an alternative to the more conservative official Salon, showcasing more progressive art. This involvement indicates his desire to support artistic innovation and provide platforms for diverse voices.

Artistic Style: Naturalism, Empathy, and Somber Realism

Jules Adler's artistic style is firmly rooted in Naturalism, yet it possesses distinctive qualities that set his work apart. His commitment to depicting reality was unwavering, but it was always tempered by a profound empathy for his subjects.

Influence of Zola and Naturalist Literature: Adler's art can be seen as a visual counterpart to the Naturalist literature of Émile Zola. Like Zola, Adler sought to explore the lives of ordinary people, the impact of heredity and environment, and the social problems plaguing contemporary society. His paintings often have a narrative quality, suggesting stories of struggle, resilience, and quiet dignity.

Color Palette and Brushwork: Adler's color palette was typically subdued, dominated by grays, browns, ochres, and muted blues and greens. This somber tonality effectively conveyed the often-grim realities of his subjects' lives and the industrial landscapes they inhabited. He avoided bright, vibrant colors that might romanticize or prettify his scenes. His brushwork was direct and unpretentious, focused on capturing form and character rather than displaying technical virtuosity for its own sake. There is a solidity and weight to his figures, grounding them firmly in their environment.

Composition and Focus: Adler's compositions are often carefully constructed to draw the viewer's attention to the human element. Even in crowd scenes, such as The Strike at Le Creusot, individual faces and gestures convey a range of emotions. He frequently used close-ups or medium shots to create a sense of intimacy and to allow the viewer to connect with his subjects on a personal level. His figures are rarely idealized; instead, they are portrayed with all their imperfections, their faces often etched with the marks of hard labor and worry.

Comparison with Contemporaries: While sharing thematic concerns with other Naturalist painters like Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, who often depicted rural labor with a sense of rustic poetry, or Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, known for his meticulously rendered scenes of peasant life and religious subjects, Adler's work often carried a more overt social critique and a focus on urban and industrial settings. He was less interested in picturesque qualities and more concerned with the raw, unvarnished truth. His work can also be seen in dialogue with artists like Constantin Meunier, the Belgian sculptor and painter who powerfully depicted industrial workers, whom Adler met in 1901 during a visit to Charleroi, facilitated by fellow painters Tancrede Synave and Charles Watelet. The influence of earlier Realists like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet is also palpable in Adler's commitment to everyday subjects and his dignified portrayal of labor. One might also consider parallels with Honoré Daumier's incisive social commentary, though Daumier's style was more caricatural.

The War Years: Witness and Contributor

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 profoundly impacted French society, and Jules Adler, then nearly fifty, responded to the conflict in his own way. While not a combatant due to his age, he contributed to the war effort through his art and his organizational activities.

During the war, he created numerous posters, illustrations, and drawings related to the conflict. These works often depicted soldiers, refugees, and scenes of wartime life, imbued with his characteristic empathy and humanism. He sought to capture the human cost of war, the suffering of civilians, and the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity. His war-related art was less about glorifying battle and more about documenting the impact of the conflict on ordinary people.

Adler also played an active role in supporting fellow artists during these difficult times. He was involved in initiatives to provide aid and assistance to artists and their families who were struggling due to the war. This commitment to his artistic community further demonstrated his compassionate nature and his sense of social responsibility. His experiences and observations during the war years undoubtedly deepened his understanding of human suffering and resilience, themes that had always been central to his art.

The interwar period saw Adler continue to paint, though perhaps with less of the overt social protest that characterized some of his earlier masterpieces. He continued to exhibit and received recognition for his contributions to French art. He was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1907, and later promoted to Officer.

World War II and Persecution

The rise of Nazism in Germany and the subsequent occupation of France during World War II brought new and terrifying challenges for Jules Adler, particularly due to his Jewish heritage. The Vichy regime, collaborating with the Nazis, implemented antisemitic laws that stripped Jews of their rights and subjected them to persecution.

Despite the dangers, Adler remained in France. In March 1944, an event occurred that starkly illustrated the perils he faced. He was denounced and arrested for painting in the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont in Paris, a public space that had been declared off-limits to Jews. This act of defiance, simply pursuing his art in a forbidden place, led to his internment. He and his wife were held at the Hôpital Rothschild in Paris, which had been converted into a detention center for Jews before potential deportation to concentration camps. Miraculously, they were not deported and survived the war. This harrowing experience undoubtedly left a deep scar, a brutal reminder of the inhumanity he had so often depicted and fought against in his art.

Later Life, Legacy, and Rediscovery

After the liberation of France, Jules Adler resumed his life and work, but the art world had changed significantly. Naturalism, the style to which he had dedicated his career, was no longer in vogue, overshadowed by modern art movements like Cubism, Surrealism, and Abstraction. Consequently, Adler's work, like that of many other Naturalist painters, gradually faded from public prominence during the mid-20th century.

He continued to paint until his death in Nogent-sur-Marne, near Paris, on June 11, 1952, at the age of 86. He left behind a substantial body of work, a testament to a life spent observing and depicting the human condition with honesty and compassion.

For several decades after his death, Jules Adler remained a somewhat overlooked figure in art history. However, in recent years, there has been a significant resurgence of interest in his work. Art historians and curators have begun to re-evaluate his contributions, recognizing the power and importance of his social realist vision. This renewed appreciation has led to several retrospective exhibitions dedicated to his art, allowing contemporary audiences to rediscover his compelling portrayals of French society at the turn of the century.

His paintings are now held in numerous public collections in France and beyond. The Musée d'Orsay in Paris, which houses a major collection of 19th and early 20th-century art, holds works like Les Halleurs (The Haulers, 1904). His birthplace, Luxeuil-les-Bains, honors him with works in the Musée de la Tour des Échevins, including Neige (Snow, 1929). The Musée des Ursulines in Mâcon holds L'Accident (1912). The Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme in Paris also features his work, acknowledging his significance as a Jewish artist who engaged with the social issues of his time. A dedicated room to Jules Adler was established in the Musée de Luxembourg as early as 1967, indicating some sustained recognition.

Auction records show a modest but present market for his works. For instance, a Portrait de femme sold for a relatively small sum in 2019, while other works like Vieillard (Old Man, 1897) have appeared with estimates in the hundreds or low thousands of euros. The true value of his work, however, lies less in its market price and more in its historical and artistic significance.

Conclusion: An Enduring Voice for the Voiceless

Jules Adler's art remains profoundly relevant today. His depictions of labor, poverty, social injustice, and the quiet dignity of ordinary people resonate with contemporary concerns about social inequality and the human cost of economic and political forces. He was more than just a skilled painter; he was a visual historian, a social commentator, and a compassionate observer of humanity.

His commitment to the "humble," his unwavering focus on the realities of their lives, and his courage in addressing contentious social issues like the Dreyfus Affair and the plight of workers, mark him as an artist of great integrity and importance. Artists like Jean Adler, his nephew, would have undoubtedly been aware of his uncle's significant path. While the grand artistic movements of his time, such as Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, often focused on light, leisure, or subjective experience, Adler, alongside fellow Naturalists like Jules Bastien-Lepage and Émile Friant, chose to illuminate the shadows of society, to give a face and a voice to those who were often marginalized and forgotten.

The renewed interest in Jules Adler's work is a testament to its enduring power. As we continue to grapple with many of the same social challenges that he depicted over a century ago, his paintings serve as a poignant reminder of the importance of empathy, social justice, and the enduring strength of the human spirit. Jules Adler, "le peintre des humbles," remains a vital and compelling figure in the rich tapestry of art history.