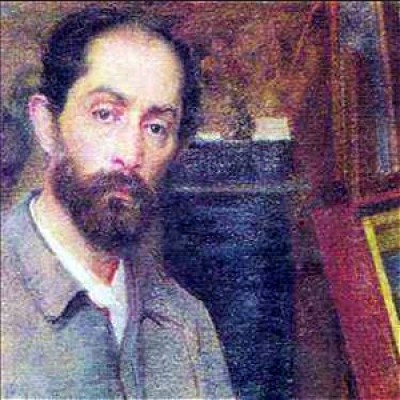

Giovanni Sottocornola (1855-1917) stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century Italian art. An accomplished painter hailing from Milan, his career was characterized by a profound engagement with Realism, a sensitive portrayal of social themes, and a dedicated exploration of the innovative techniques of Divisionism. His work offers a compelling window into the artistic and social currents of his time, reflecting both the everyday lives of ordinary people and the avant-garde artistic theories that were reshaping European art.

Early Life and Academic Foundations in Milan

Born in Milan in 1855, Giovanni Sottocornola's artistic journey began in one of Italy's most vibrant cultural and industrial centers. The city, undergoing rapid transformation, would later provide rich subject matter for his socially conscious art. His formal artistic training commenced in 1875 when he enrolled at the prestigious Brera Academy of Fine Arts (Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera) in Milan. The Brera was a crucible of artistic talent and a hub for both traditional instruction and emerging ideas.

At the Brera, Sottocornola studied under the guidance of respected painters such as Raffaele Casnedi and Giuseppe Bertini. Casnedi was known for his historical and religious paintings, often executed with a refined academic technique, while Bertini, also a professor and later director of the Brera, was celebrated for his grand historical scenes, portraits, and decorative frescoes, including work in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli. This academic grounding provided Sottocornola with a strong technical foundation in drawing, composition, and color.

During his formative years at the Brera, Sottocornola was not in isolation. He was part of a dynamic cohort of students who would go on to become leading figures in Italian art. Among his contemporaries and fellow students were Gaetano Previati, Emilio Longoni, and the celebrated Giovanni Segantini. These artists, each with their unique trajectory, would collectively contribute to the evolution of Italian painting, particularly through their engagement with Symbolism and Divisionism. The shared experiences and artistic dialogues within this circle undoubtedly played a role in shaping Sottocornola's own artistic path.

The Emergence of Divisionism in Italy

To understand Sottocornola's mature work, it is essential to grasp the significance of Divisionism (Divisionismo) in Italy. Emerging in the late 1880s and flourishing into the early 20th century, Divisionism was Italy's distinctive response to the broader European Neo-Impressionist movement, most famously associated with French artists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. Like its French counterpart (Pointillism), Divisionism was rooted in contemporary scientific theories of optics and color.

The core principle of Divisionism involved applying color to the canvas in small, distinct dots or strokes of pure, unmixed pigment. The intention was that these juxtaposed colors would be optically blended in the viewer's eye, rather than on the palette, to achieve greater luminosity and vibrancy. Italian Divisionists, however, often employed longer, more filament-like brushstrokes compared to the precise dots of French Pointillism, and their thematic concerns frequently leaned towards Symbolism, social issues, and landscape, imbued with a particular Italian sensibility.

Key figures in the development and popularization of Italian Divisionism, alongside Sottocornola's Brera classmates, included Vittore Grubicy De Dragon, who was not only a painter but also a critic and dealer who played a crucial role in promoting the movement. Angelo Morbelli became known for his poignant depictions of the elderly and scenes of social life, rendered with meticulous Divisionist technique. Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo is perhaps most famous for his monumental work Il Quarto Stato (The Fourth Estate), a powerful symbol of working-class solidarity, executed in the Divisionist style. Plinio Nomellini also contributed significantly with his vibrant landscapes and allegorical scenes.

Sottocornola's Adoption of Divisionist Principles

Initially, Sottocornola's work, like that of many of his contemporaries, was grounded in the prevailing Realist traditions. He produced portraits and still lifes that demonstrated his academic skill and found a degree of success in the art market. However, influenced by the intellectual ferment around him and the pioneering efforts of artists like Segantini and Previati, Sottocornola began to explore the expressive possibilities of Divisionism.

His transition towards Divisionism was not merely a technical shift but was also intertwined with his evolving thematic interests. The technique, with its emphasis on light and its ability to create shimmering, atmospheric effects, lent itself well to his desire to depict the realities of modern life with heightened emotional and visual impact. He saw in Divisionism a means to move beyond mere representation towards a more profound engagement with his subjects.

Sottocornola's application of Divisionist techniques was characterized by a careful, almost scientific, approach to color, yet always in service of the subject's emotional resonance. He used the separation of colors to enhance the play of light, to model form, and to create a sense of atmosphere, whether in an urban street scene, a rural landscape, or an intimate domestic interior. This stylistic evolution marked a significant phase in his career, aligning him with the avant-garde of Italian art.

Themes of Labor and Social Consciousness

A defining characteristic of Giovanni Sottocornola's oeuvre is his consistent focus on social themes, particularly the lives and struggles of the working class. In an era of industrialization and growing social awareness, Sottocornola, like other artists such as Constantin Meunier in Belgium or Käthe Kollwitz in Germany, turned his gaze towards the everyday realities of laborers, their environments, and their aspirations.

His most iconic work in this vein is undoubtedly L'alba dell'operaio (The Dawn of the Worker, or Worker's Dawn), completed in 1897. This painting depicts a worker and his family in the early morning light as he prepares to leave for work. The scene is imbued with a quiet dignity and a sense of shared purpose. Sottocornola employs Divisionist techniques to capture the subtle gradations of light filtering into the modest dwelling, highlighting the figures and creating an atmosphere that is both somber and hopeful. The painting is a powerful testament to the resilience and humanity of the working class, avoiding overt political sloganeering in favor of a more intimate, empathetic portrayal. A preparatory study, Studio per Alba dell'Operaio (Study for the Dawn of the Worker), dating from 1891-1897, shows his meticulous process in developing this seminal piece.

Other works also reflect this social engagement. Pirelli factory workers' break (the exact title might vary, but refers to depictions of workers from the Pirelli factory) captures a moment of respite in the demanding lives of industrial laborers. Such paintings served not only as artistic expressions but also as social documents, reflecting the changing fabric of Italian society. Sottocornola's commitment to these themes places him firmly within the tradition of Social Realism, yet his use of the modern Divisionist technique distinguishes his approach.

Depictions of Everyday Life, Family, and Nature

While depictions of labor were central to his work, Sottocornola's thematic range extended to other aspects of contemporary life, including intimate family scenes, portraits, and landscapes. He approached these subjects with the same sensitivity and keen observation that characterized his social realist works.

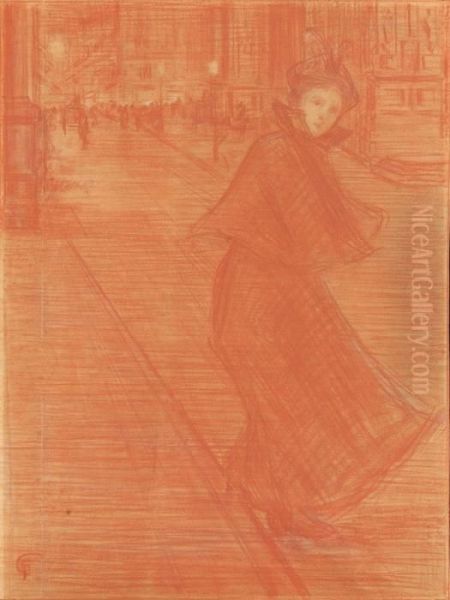

Paintings like Chiacchie (Chats or Gossip) likely capture informal social interactions, perhaps among women in a domestic or local setting, reflecting the texture of community life. His work Piazza Duomo, which is noted for depicting elegant female figures, suggests an interest in the varied social strata of Milan, contrasting with his portrayals of working-class life. This demonstrates his capacity to observe and render different facets of the urban experience.

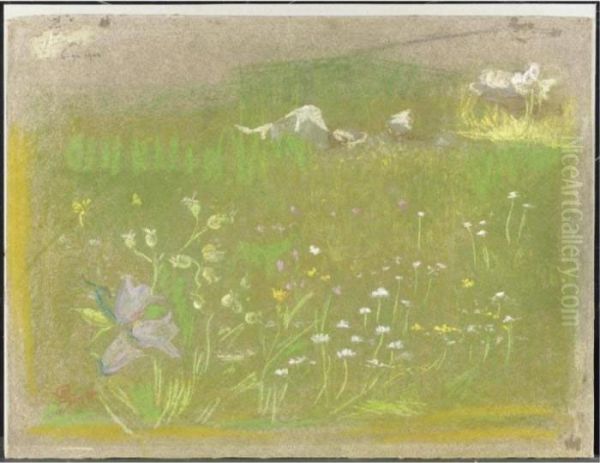

Sottocornola also found inspiration in the natural world and rural life. Prato fiorito (Flowering Meadow) indicates his engagement with landscape painting, a genre also explored by many Divisionists like Segantini, who often imbued their Alpine scenes with symbolic meaning. For Sottocornola, nature could offer a counterpoint to the industrial city, a space for tranquility or a different kind of labor. His depictions of rural scenes or animal portraits, such as a piece sometimes referred to as Shepherd with Animals, showcase his versatility and his ability to capture the essence of his subjects, whether human or animal, with directness and vitality.

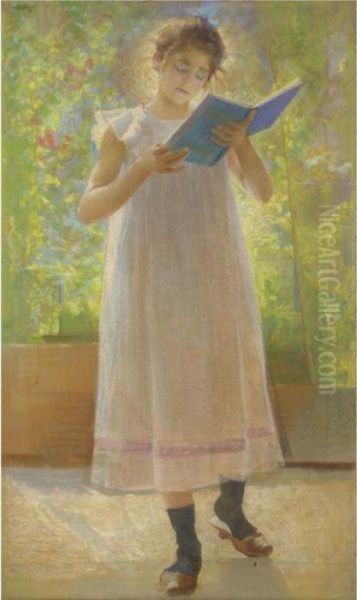

His later work, La preferita (The Favorite, 1912), suggests a continued interest in genre scenes and portraiture, possibly with a more personal or allegorical inflection as his style evolved. The painting Libro azzurro (Blue Book, 1900) might hint at a more symbolic or introspective theme, common among artists at the turn of the century who were exploring the inner life and subjective experience.

Artistic Style: From Realism to Divisionist Symbolism

Giovanni Sottocornola's artistic style underwent a significant evolution, moving from a solid academic Realism to a sophisticated engagement with Divisionism, often tinged with Symbolist undertones. His early training at the Brera provided him with the technical proficiency evident in his initial portraits and still lifes. These works would have adhered to the conventions of accurate representation and careful modeling.

The adoption of Divisionism marked a pivotal change. This technique, as practiced by Sottocornola, involved the meticulous application of divided color to achieve heightened luminosity and optical vibrancy. His brushwork, while adhering to Divisionist principles, could vary from smaller dabs to more elongated strokes, adapted to the specific needs of the composition and the desired atmospheric effect. This method allowed him to explore the nuances of light and color in a way that traditional academic painting could not.

Beyond the technical aspects, Sottocornola's style also reflected a shift in artistic intent. While his subjects often remained rooted in reality, his Divisionist approach could imbue them with a poetic or symbolic quality. The shimmering light and vibrant color palettes were not merely descriptive but also served to convey emotion and atmosphere. In works like L'alba dell'operaio, the light itself becomes a symbolic element, representing hope, the passage of time, or the dawning of a new era. This subtle infusion of symbolic meaning, common among many Divisionists, shows a move from straightforward Realism towards a more evocative and subjective form of expression, aligning with broader Symbolist trends in European art championed by artists like Gustave Moreau or Odilon Redon in France, or Fernand Khnopff in Belgium.

His diverse output, encompassing oil paintings, watercolors, and charcoal drawings, demonstrates a mastery across different media, each chosen to suit the expressive needs of the subject. The "direct and modern effect" noted in his work speaks to his ability to combine technical innovation with a contemporary sensibility.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Later Career

Throughout his career, Giovanni Sottocornola actively participated in the art world, exhibiting his works in prominent venues. He was a regular presence at exhibitions in Milan, including those held at the Brera Academy, which were important platforms for artists to gain recognition and connect with patrons and critics. His participation in exhibitions in Venice, likely including the prestigious Venice Biennale (established in 1895), further indicates his standing within the Italian art scene.

The success of his early works, particularly portraits and still lifes, provided him with a degree of financial stability and recognition. As he embraced Divisionism and social themes, his work continued to attract attention, contributing to the broader discourse around modern art in Italy. While perhaps not achieving the same level of international fame as Giovanni Segantini or the widespread national recognition of Pellizza da Volpedo for Il Quarto Stato, Sottocornola was a respected figure whose contributions were acknowledged by his peers and the exhibiting public.

In his later years, Sottocornola continued to paint, producing portraits and landscape works. His artistic practice also extended to teaching and restoration, activities that suggest a deep commitment to the preservation and transmission of artistic knowledge and heritage. These roles would have further integrated him into the artistic community and allowed him to share his expertise with a younger generation. He passed away in Milan in 1917, leaving behind a body of work that reflects the artistic dynamism and social consciousness of his era.

Sottocornola's Network: Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Giovanni Sottocornola's artistic development and career were deeply embedded within a network of influential contemporaries. His time at the Brera Academy was crucial in forging these connections. His classmates Gaetano Previati, Emilio Longoni, and Giovanni Segantini were not just fellow students but collaborators in the burgeoning Divisionist movement. Previati became a leading theorist of Divisionism and a prominent Symbolist painter. Longoni also embraced Divisionism, often focusing on social themes and landscapes. Segantini, perhaps the most internationally renowned of the group, developed a powerful and unique Divisionist style, particularly in his depictions of Alpine life.

Beyond this core group, Sottocornola was part of the broader circle of Italian Divisionists. Angelo Morbelli, with his meticulous technique and poignant social subjects, shared thematic concerns with Sottocornola. Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, another key Divisionist, created iconic works of social commentary. Vittore Grubicy De Dragon, as a critic, gallerist, and painter, was instrumental in promoting Divisionism and fostering a sense of collective identity among its practitioners. These artists, along with others like Plinio Nomellini, formed a vibrant artistic community, exchanging ideas, exhibiting together, and collectively pushing the boundaries of Italian art.

The influence of their teachers, Raffaele Casnedi and Giuseppe Bertini, provided an academic foundation, but it was the interaction with these progressive peers that propelled Sottocornola towards the avant-garde. The artistic environment in Milan, a city at the forefront of Italian modernity, provided fertile ground for such innovations. The influence of French Neo-Impressionists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac was also palpable, transmitted through publications, exhibitions, and artists traveling between Italy and France. Sottocornola's work, therefore, can be seen as part of a wider European conversation about the future of painting.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Giovanni Sottocornola's legacy lies in his contribution to Italian Divisionism and his sensitive portrayal of social realities at the turn of the 20th century. While he may not be as widely known internationally as some of his contemporaries, his work holds an important place in the narrative of Italian modern art. His masterpiece, L'alba dell'operaio, remains a significant example of Social Realism rendered through the innovative lens of Divisionism, capturing the dignity of labor with a unique blend of technical skill and empathetic observation.

His exploration of Divisionist techniques contributed to the movement's richness and diversity in Italy. By applying these principles to a range of subjects, from working-class life to landscapes and portraits, he demonstrated the versatility and expressive power of the style. His work helped to solidify Divisionism as a major force in Italian art, bridging the gap between 19th-century Realism and the emerging avant-garde movements of the early 20th century, such as Futurism, whose leading figures like Umberto Boccioni and Gino Severini initially passed through a Divisionist phase.

Sottocornola's dedication to depicting the lives of ordinary people also ensures his relevance. In an era marked by profound social and economic change, his art provides a valuable historical and human perspective. His paintings invite viewers to reflect on the conditions of labor, the importance of family, and the search for beauty and meaning in everyday existence.

Museums and collections in Italy, particularly those focusing on Ottocento (19th century) and early Novecento (20th century) art, preserve his work, allowing contemporary audiences to appreciate his skill and vision. Scholarly interest in Italian Divisionism continues to grow, and with it, a deeper understanding of Sottocornola's specific contributions and his place within this pivotal movement. He remains a testament to an artist who successfully synthesized advanced artistic techniques with a profound humanism.

Conclusion: An Enduring Voice in Italian Art

Giovanni Sottocornola was an artist of his time, deeply engaged with the social and artistic currents that defined late 19th and early 20th-century Italy. From his academic beginnings at the Brera Academy to his mature embrace of Divisionism, his career was marked by a commitment to both technical innovation and meaningful subject matter. His depictions of the working class, particularly L'alba dell'operaio, stand as enduring statements of social consciousness, while his broader oeuvre reveals a versatile artist capable of capturing the nuances of human experience and the beauty of the world around him.

As a key member of the Italian Divisionist movement, alongside luminaries like Segantini, Previati, Longoni, Morbelli, and Pellizza da Volpedo, Sottocornola played a vital role in shaping a distinctly Italian response to European modernism. His ability to meld the scientific principles of color theory with a profound empathy for his subjects resulted in works that are both visually striking and emotionally resonant. Though perhaps not always in the brightest spotlight, Giovanni Sottocornola's contributions to Italian art history are undeniable, and his paintings continue to speak to audiences with their honesty, skill, and quiet power.