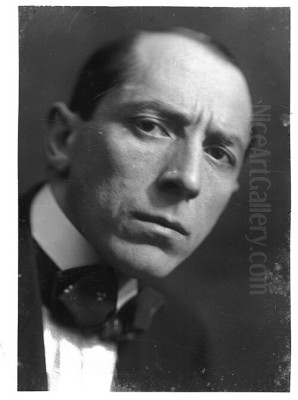

Umberto Boccioni stands as one of the most significant and dynamic figures of early 20th-century modern art. An Italian painter, sculptor, and the leading theorist of the Futurist movement, Boccioni's relatively short but intensely productive career left an indelible mark on the course of art history. His work passionately embraced the energy, speed, and technological fervor of the modern age, seeking new visual languages to capture the dynamism of life in the industrial era. Though his life was tragically cut short by World War I, his artistic vision and theoretical contributions continue to resonate, defining a crucial moment of avant-garde rupture and innovation.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Reggio Calabria in the south of Italy in 1882, Umberto Boccioni's origins were relatively modest. His father worked as a minor government employee, and the family moved frequently due to his postings. This early exposure to different parts of Italy may have contributed to Boccioni's later sensitivity to the changing landscape of the nation. His formal artistic training began in Rome, where he moved around the turn of the century. This period proved crucial for his development.

In Rome, Boccioni, along with his friend Gino Severini, sought out the tutelage of Giacomo Balla, an established painter already exploring techniques derived from Divisionism. Balla introduced them to the principles of painting with divided colors, applying small strokes or dots of pure color directly to the canvas, allowing the viewer's eye to optically mix them. This technique, pioneered by French Neo-Impressionists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, aimed for greater luminosity and vibrancy. Balla adapted it to depict light and movement, an interest that would become central to Boccioni's own work.

During these formative years, Boccioni absorbed various influences. He traveled, visiting Paris in 1906, where he encountered Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painting firsthand. The expressive color and emotional intensity of artists like Edvard Munch also left an impression. His early works show a mastery of Divisionist technique, often depicting suburban landscapes, portraits, and scenes of everyday life, but already hinting at an underlying interest in capturing more than just the surface appearance of reality. He also spent time in Russia, further broadening his artistic horizons.

The Futurist Awakening in Milan

A pivotal moment came when Boccioni moved to Milan in 1907. Milan, unlike the more historically saturated Rome, was Italy's burgeoning industrial and financial capital, a city crackling with modern energy, factories, trams, and a sense of rapid transformation. This environment proved highly stimulating for Boccioni and aligned perfectly with the emerging Futurist ideology.

In 1909, the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti published the Founding and Manifesto of Futurism on the front page of the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro. This explosive text called for a radical break with the past, denouncing museums, libraries, and academies as "cemeteries." It glorified speed, machinery, violence, and war, proclaiming that "a racing car whose hood is adorned with great pipes, like exploding snakes with explosive breath... a roaring car that seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace."

Boccioni, along with Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla (who had also moved north), and Gino Severini (based in Paris but closely connected), enthusiastically embraced Marinetti's call to arms. They saw in Futurism a way to revitalize Italian culture and bring art into direct confrontation with the dynamism of modern life. Boccioni quickly emerged not just as a key painter but also as the group's most articulate and influential theorist.

Manifesting the Future: Painting

In 1910, Boccioni was the primary author, along with Carrà, Russolo, Balla, and Severini, of the Manifesto of Futurist Painters. This was swiftly followed by the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting. These documents laid out the core principles of their artistic program. They declared their intention to "sweep away from the field of art all motifs and subjects that have been used previously" and to express the "vortex of modern life – a life of steel, fever, pride and headlong speed."

Key concepts included "universal dynamism," the idea that all objects are in constant motion and interact with their surroundings. They rejected traditional notions of fixed perspective and static representation. Instead, they aimed to depict "dynamic sensation itself." The Technical Manifesto elaborated on this, stating, "The gesture which we would represent on canvas shall no longer be a fixed moment in universal dynamism. It shall simply be the dynamic sensation itself." They spoke of "lines of force" that would reveal how objects interact and resolve themselves into the surrounding space, and the "simultaneity" of vision, combining memory, present sensation, and anticipation. This owed something to the contemporary philosophical ideas of Henri Bergson concerning duration and intuition.

The Canvas in Motion: Key Paintings

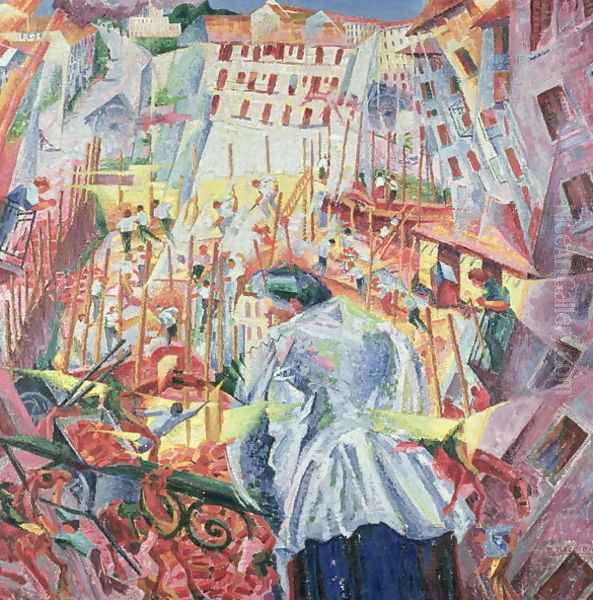

Boccioni's paintings from this period vividly translate these theories into practice. The City Rises (La città che sale), completed in 1910, is widely considered one of the first major Futurist paintings and a masterpiece of the movement. Originally titled Lavoro (Work), it depicts a chaotic scene of construction on the outskirts of Milan. Huge, straining horses dominate the foreground, symbolizing the raw energy of labor and progress, while figures of workers merge with the dynamic lines of force emanating from the burgeoning cityscape behind them. The vibrant, almost violent use of Divisionist color technique enhances the sense of energy and upheaval.

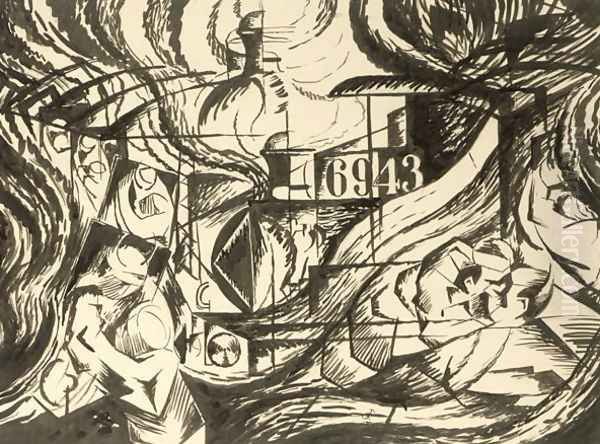

The triptych States of Mind (Stati d'animo), painted in 1911, explores the psychological and emotional dimensions of modern experience, specifically centered around the theme of departure at a train station. The three panels – The Farewells, Those Who Go, and Those Who Stay – use fragmented forms, swirling lines, and interpenetrating planes to convey different emotional states. The Farewells captures the chaotic energy and emotional intensity of departure, with figures and the locomotive dissolving into waves of force. Those Who Go depicts the sensation of speed and forward motion from the perspective of passengers on the train, while Those Who Stay evokes a sense of melancholy and stillness through vertical lines and somber colors.

Another significant work from 1911 is The Laugh (La risata). Here, Boccioni uses fragmented forms and dynamic lines radiating outwards from a central laughing figure in a café, attempting to capture not just the person but the entire atmosphere and sensory experience of the bustling modern environment. These works demonstrate Boccioni's rapid assimilation and transformation of influences, moving beyond Divisionism towards a more complex engagement with form and space.

Encountering Cubism

The development of Futurism was significantly impacted by the artists' encounter with Cubism. In late 1911, Boccioni, Carrà, and Russolo traveled to Paris, facilitated by Severini. There, they saw firsthand the works of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Cubism's fragmentation of objects, its depiction of multiple viewpoints simultaneously, and its challenge to traditional perspective offered the Futurists powerful new tools.

However, Boccioni and his colleagues were quick to distinguish their aims from those of the Cubists. While they adopted aspects of Cubist formal language – the geometric faceting of forms, the interpenetration of planes – they criticized Cubism for being too static and overly analytical. Boccioni argued that Cubism dissected objects but failed to put them back together in a dynamic synthesis that captured life's constant flux. The Futurists sought to use these techniques not merely to analyze form, but to express speed, energy, and the sensation of movement itself. This adaptation of Cubist principles for Futurist ends is evident in works like States of Mind and Boccioni's subsequent paintings and sculptures.

Sculpting the Fourth Dimension

In 1912, Boccioni turned his attention seriously to sculpture, believing it offered unique possibilities for realizing Futurist ideals in three dimensions. He published the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture, another foundational text. In it, he declared war on the limitations of traditional sculpture, particularly its reliance on noble materials like marble and bronze and its focus on the closed, static human form.

He called for the "absolute and complete abolition of finite lines and the contained statue." Instead, he advocated for sculpture that would "open up the figure like a window and include it in the environment in which it lives." This concept of "environmental sculpture" aimed to break down the barrier between the sculpted object and its surroundings, suggesting that forms should interpenetrate and influence each other. He proclaimed the need to use a wide range of materials – glass, wood, cardboard, iron, cement, horsehair, leather, cloth, mirrors, electric lights – to directly express the dynamism and material reality of modern life. While his theoretical ambitions for materials were radical, in practice, Boccioni often worked with plaster, intending his sculptures for later casting in bronze, a somewhat more traditional approach than his manifesto suggested.

Masterpiece in Bronze: Unique Forms of Continuity in Space

Boccioni's most famous and arguably most successful sculpture is Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio), conceived in plaster in 1913. This iconic work depicts a striding human figure, abstracted and streamlined to convey powerful forward motion. The form is not represented realistically but is instead sculpted by the forces acting upon it – the "lines of force" and the resistance of the atmosphere. Muscle, bone, and drapery merge into fluid, flame-like shapes that seem to carve through space.

The sculpture embodies the Futurist obsession with speed and dynamism. While it evokes classical precedents like the Nike of Samothrace, it radically transforms them into a symbol of the modern machine age. The figure appears almost aerodynamic, its contours blurred by velocity. It achieves Boccioni's aim of representing "synthetic continuity" rather than analytical discontinuity. Although originally created in plaster, several bronze casts were made posthumously, and the image is now instantly recognizable, even appearing on the Italian 20-cent Euro coin. It remains a definitive statement of Futurist sculpture.

Other important sculptures include Development of a Bottle in Space (1912), where Boccioni applied Futurist principles to a still-life object, analyzing its structure and its interaction with the surrounding space, and dynamic sculptural portraits like Antigraceful (The Mother) (1912). These works further explored the interpenetration of form and environment, breaking down the solidity of objects to reveal their inner energy and relationship to their surroundings.

War, Nationalism, and Untimely Death

Like Marinetti and other Futurists, Boccioni was an ardent nationalist and interventionist, believing that Italy's participation in World War I was necessary for the nation's modernization and revitalization. The Futurists saw war as the ultimate expression of dynamism and cleansing force – "the world's only hygiene," as Marinetti had proclaimed.

When Italy entered the war in 1915, Boccioni eagerly volunteered, serving in the Lombard Volunteer Cyclist Battalion along with Marinetti, Russolo, and the Futurist architect Antonio Sant'Elia. His patriotic fervor was intense; earlier, he had been arrested along with Marinetti for participating in a pro-war demonstration that involved burning an Austrian flag in Milan.

His frontline experience, however, seems to have tempered some of his initial enthusiasm, though his belief in the cause remained. After a period of service, he found time during leave to paint again, producing some striking portraits. His artistic journey, however, was abruptly and tragically cut short. In August 1916, during a cavalry training exercise near Verona, Boccioni fell from his horse. He died the following day, aged just 33.

His death was a devastating blow to the Futurist movement. Boccioni had been its most talented visual artist and its most sophisticated theorist. His loss marked a turning point, and while Futurism continued, it arguably never regained the same level of artistic innovation and intellectual rigor that Boccioni had provided. The deaths of Sant'Elia and other artists in the war further depleted the movement's creative energy.

Boccioni's Enduring Legacy

Despite his short life, Umberto Boccioni's impact on 20th-century art was profound. He was instrumental in shaping Futurism, translating Marinetti's literary provocations into a powerful visual language. His unique contribution lay in his ability to synthesize diverse influences – the color theory of Divisionism, the structural analysis of Cubism, the philosophical ideas of Bergson – into a coherent and dynamic artistic vision focused on capturing the essence of modernity.

His paintings, like The City Rises and States of Mind, remain compelling depictions of urban energy and psychological flux. His sculpture, particularly Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, became an icon of modern art, embodying the Futurist fascination with speed and the machine. His theoretical writings provided a crucial intellectual framework for the movement and influenced subsequent generations of artists.

Boccioni's exploration of dynamism and the representation of movement had repercussions beyond Futurism. Echoes of his ideas can be seen in various subsequent movements, including Vorticism in Britain (led by Wyndham Lewis, with artists like C.R.W. Nevinson exploring similar themes of modern warfare and machinery), and potentially influencing aspects of Russian Constructivism and later Kinetic Art. While contemporaries in Paris like Amedeo Modigliani pursued different, more figurative paths, Boccioni's radicalism helped push the boundaries of representation. His work continues to be studied and exhibited worldwide, recognized for its historical importance and its enduring power to convey the exhilarating and often unsettling experience of modern life.

Conclusion

Umberto Boccioni was more than just a painter or a sculptor; he was a visionary who sought to redefine the very purpose and language of art in the face of unprecedented technological and social change. As the driving force behind Futurist visual art, he created works that pulsed with the energy, speed, and conflict of the early 20th century. His premature death was a profound loss, but his legacy endures in his iconic artworks and influential theories. He remains a pivotal figure in the story of modernism, an artist who dared to capture the dynamism of a world in rapid, and often violent, transformation.