Georges Paul François Laugée stands as a significant figure in French art during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born into an artistic family and trained within the established academic system, he dedicated his career to capturing the essence of French rural life. His paintings, executed primarily in the Realist and Naturalist styles, offer poignant and dignified portrayals of peasants, farm labourers, and the landscapes they inhabited. Laugée's work resonated with audiences both in France and abroad, securing him numerous accolades and a lasting place in the narrative of French genre painting.

An Artistic Heritage: Early Life and Training

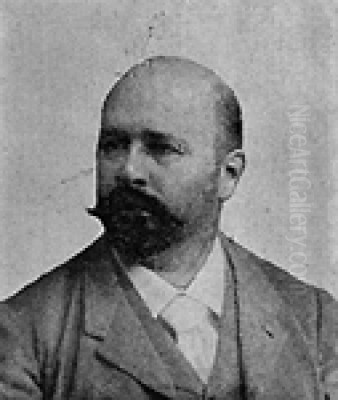

Georges Laugée was born on December 19, 1853, in Montivilliers, Seine-Maritime, France. His artistic path seemed almost preordained, as his father was the highly respected painter Désiré-François Laugée (1823-1896). Désiré was a prominent figure in the Realist movement, known for his sensitive depictions of peasant life and historical subjects, often drawing comparisons to his contemporary, the celebrated painter Jules Breton. Growing up in this environment provided Georges with an invaluable early education in the arts.

He received his initial artistic instruction directly from his father, absorbing the principles of Realism and developing a foundational understanding of drawing and painting techniques. This paternal guidance instilled in him a deep appreciation for the subject matter that would dominate his own career: the daily lives and labours of the rural populace. His father's studio was his first classroom, offering practical experience and exposure to the professional art world of the time.

Seeking formal training, Georges Laugée enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. This institution was the cornerstone of academic art education in France, emphasizing rigorous training in drawing, composition, and the study of Old Masters. During his time there, he studied under notable academic painters Isidore Pils (1813-1875) and Henri Lehmann (1814-1882). Pils was known for his historical and military scenes, while Lehmann was a respected portraitist and history painter in the Neoclassical tradition. Studying under these masters provided Laugée with the technical proficiency and discipline characteristic of academic training.

While at the École des Beaux-Arts, Laugée formed important connections. It was here he met and befriended Julien Dupré (1851-1910), another aspiring artist who would become a lifelong friend and colleague. Dupré, like Laugée, would dedicate his career to depicting scenes of rural labour, particularly harvest scenes featuring robust peasant figures. Their shared artistic interests and training fostered a close bond that endured throughout their careers.

Embracing Realism and Naturalism

Laugée's artistic style is firmly rooted in the traditions of French Realism and Naturalism. Emerging in the mid-nineteenth century, Realism, championed by artists like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, sought to depict ordinary life and contemporary subjects with unvarnished truthfulness, rejecting the idealized Neoclassical and Romantic traditions. Naturalism, developing slightly later, shared Realism's focus on everyday subjects but often incorporated a more detailed, almost scientific observation of reality, sometimes influenced by photographic aesthetics and contemporary social theories.

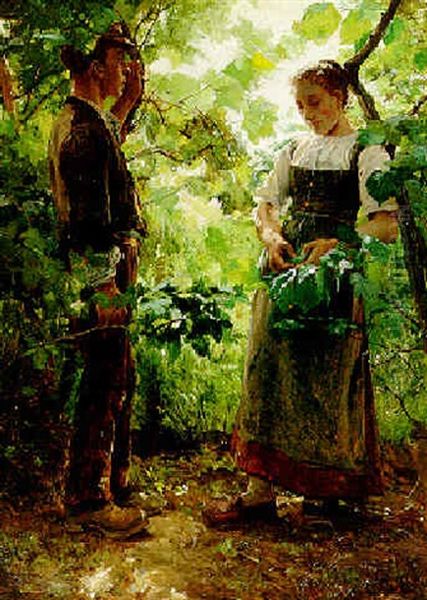

Laugée skillfully blended these influences. His work demonstrates the solid compositional structure and technical finish valued by the Academy, yet his true passion lay in portraying the authentic experiences of country folk. He avoided overt sentimentality, instead imbuing his subjects with a quiet dignity and highlighting the rhythm of their connection to the land. His paintings often focus on specific tasks: gleaning leftover grain after the harvest, tending livestock, pausing for rest in the fields, or returning home after a day's work.

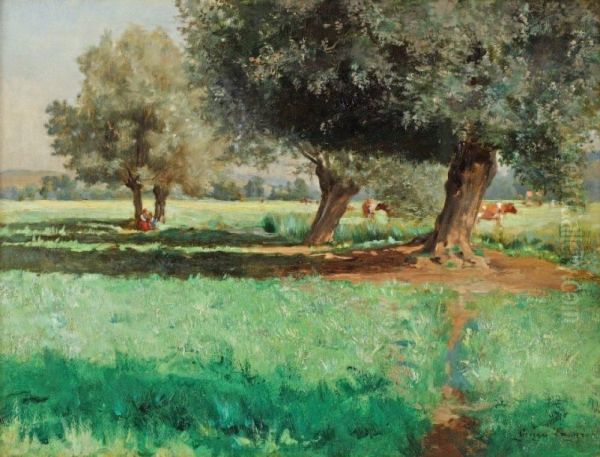

A key characteristic of Laugée's style is his sensitive handling of light. While fundamentally a Realist, he absorbed some lessons from the Impressionist movement, which was gaining prominence during his formative years. His paintings often feature a luminous quality, capturing the specific effects of sunlight at different times of day – the bright glare of midday, the warm glow of late afternoon, or the soft light of early morning. This attention to atmospheric effects adds vibrancy and immediacy to his rural scenes, enhancing their realistic feel without fully adopting the broken brushwork or colour theories of Impressionism.

His commitment was to represent the visual truth of the scene before him, filtered through his artistic sensibility. The textures of rough-spun clothing, the strain of physical labour, the placid nature of farm animals, and the specific qualities of the Picardy landscape are all rendered with care and precision. He presented the life of the peasant not as idyllic, but as one defined by hard work, resilience, and an intimate relationship with nature.

The Picardy Countryside: Muse and Subject

Much of Laugée's most characteristic work was inspired by the landscapes and people of the Picardy region in northern France. His family had roots there, particularly around the area of Saint-Quentin and Nauroy, where his father had also painted extensively. Georges Laugée spent considerable time living and working in this region, developing a deep familiarity with its specific geography, agricultural cycles, and the character of its inhabitants.

His paintings often depict the vast, open fields characteristic of Picardy, under expansive skies. He captured the changing seasons, from the planting and sowing in spring to the intense labour of the summer harvest and the quieter tasks of autumn and winter. The figures in his paintings are not generic peasants but seem drawn from direct observation, reflecting the specific dress and physiognomy of the local population.

Works like Bringing in the Harvest or scenes depicting gleaners showcase his focus on communal agricultural activities. These paintings often feature multiple figures working together, emphasizing the collective nature of farm labour. Other works might focus on more solitary moments, such as a young shepherdess watching her flock (Le Pâturage) or a woman milking a cow (Milking Time). In each case, the setting is rendered with as much care as the figures, grounding them firmly in their environment.

His time spent living in Nauroy, particularly during the difficult years of World War I, further deepened his connection to the region, though the war brought personal tragedy and undoubtedly affected the tenor of life he had previously depicted. Nonetheless, the fields, farms, and villages of Picardy remained his primary source of inspiration throughout his long career.

Representative Works: Capturing Moments of Rural Life

Several paintings stand out as particularly representative of Georges Laugée's oeuvre, showcasing his typical themes and stylistic approach.

Au printemps de la vie (In the Springtime of Life): This work, which earned him a silver medal at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, likely depicted youthful figures in a rural setting, embodying themes of growth, renewal, and the connection between human life and the natural cycles. The title itself suggests an optimistic and perhaps slightly idealized view, characteristic of some Salon paintings aiming for broader appeal.

Le Préféré (The Favorite): Often depicting a young farm girl feeding a favored calf or lamb, this theme highlights the gentle interactions between humans and animals in a farm setting. Such works allowed Laugée to explore tenderness and care within the context of rural life, appealing to contemporary tastes for charming genre scenes.

Bringing in the Harvest: This title represents a recurring theme in Laugée's work, as well as that of his friend Julien Dupré. These paintings typically show groups of peasants working together in sun-drenched fields, gathering sheaves of wheat or hay. They emphasize the physical exertion and communal effort involved in this crucial agricultural activity, often rendered with dynamic compositions and attention to the effects of bright sunlight.

Milking Time: Another common rural chore depicted by Laugée. These scenes often feature a woman or girl milking a cow in a barn or pasture. They provided an opportunity to capture quiet, domestic moments within the agricultural world and demonstrate skill in rendering animal anatomy and the textures of the farm environment. One such painting gained particular fame through its inclusion in American school readers.

En Octobre (In October): This painting, exhibited at the 1881 Paris Salon where Laugée won a third-class medal (along with Le Mendiant or The Beggar), likely depicted autumnal tasks or landscapes. October scenes often involved late harvests, potato gathering, or the changing colours of the foliage, allowing for a different palette and mood compared to his summer harvest scenes.

These examples illustrate Laugée's consistent focus on the activities, figures, and atmosphere of the French countryside. His works offered viewers, many of whom lived in increasingly urbanized environments, a glimpse into a world perceived as more traditional, authentic, and connected to the rhythms of nature.

Recognition, Exhibitions, and Awards

Georges Laugée achieved considerable success within the established art system of his time. He began exhibiting regularly at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1877. The Salon, organized annually by the Académie des Beaux-Arts (and later by the Société des Artistes Français), was the most important venue for artists to display their work and gain recognition from critics, collectors, and the state.

His talent was acknowledged early on. In 1881, he was awarded a third-class medal at the Salon for his paintings En Octobre and Le Mendiant. This official recognition was a significant step in establishing his reputation. He continued to exhibit frequently at the Salon throughout his career.

Laugée also participated in the great Expositions Universelles (World's Fairs) held in Paris, which were major international showcases for art and industry. At the 1889 Exposition Universelle, celebrating the centenary of the French Revolution, he received a bronze medal. This further solidified his standing among contemporary French painters.

His greatest official accolade came at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, where he was awarded a silver medal for his painting Au printemps de la vie. Receiving a silver medal at such a major international event represented a high point in his career, confirming his status as a respected artist both nationally and internationally. Some sources also mention participation or awards at other international exhibitions, such as the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, reflecting the growing transatlantic interest in French academic and Realist art during this period.

This consistent record of participation and awards at the most important official venues demonstrates that Laugée successfully navigated the competitive art world of the Third Republic, earning the respect of juries and the appreciation of the public for his skillful and appealing depictions of rural France.

Artistic Context: Contemporaries and Influences

Georges Laugée's work should be understood within the broader context of late nineteenth-century French art, particularly the flourishing movements of Realism and Naturalism. His artistic development was shaped by direct mentors, close colleagues, and the prevailing artistic currents of his time.

His most immediate influence was undoubtedly his father, Désiré-François Laugée. From him, Georges inherited not only technical skills but also a thematic focus on rural labour and a commitment to Realist principles. Désiré's success and connections likely eased Georges's entry into the art world.

His teachers at the École des Beaux-Arts, Isidore Pils and Henri Lehmann, provided him with a strong academic foundation, emphasizing drawing, composition, and a polished technique. While Laugée moved towards Realist subjects rather than the historical or Neoclassical themes favored by his teachers, their training remained evident in the structure and finish of his work.

His close friendship with Julien Dupré was significant. They shared a similar artistic trajectory, both studying at the École and dedicating themselves to Naturalist depictions of peasant life, particularly harvest scenes. They likely exchanged ideas and perhaps even painted together in the countryside, mutually reinforcing their commitment to this genre.

Laugée worked during a period when the legacy of earlier Realists like Jean-François Millet (1814-1875) and Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) was profound. Millet's solemn and dignified portrayals of peasants in works like The Gleaners and The Angelus set a powerful precedent for treating rural labour as a serious artistic subject. Courbet's revolutionary insistence on depicting contemporary reality, however mundane, had opened the door for artists like Laugée.

Among his direct contemporaries specializing in similar themes were several notable figures. Jules Breton (1827-1906), often compared to Laugée's father, was immensely popular for his somewhat idealized yet beautifully painted scenes of rural life. Léon Lhermitte (1844-1925) was another master of the genre, known for his large-scale, highly detailed depictions of farm workers, often using pastel as well as oil. Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848-1884), though his career was tragically short, was a leading figure of Naturalism, admired for his psychologically penetrating portraits and meticulously rendered rural scenes like Haymaking.

Other important Naturalist painters included Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret (1852-1929), known for his Breton peasant scenes and religious subjects rendered with photographic precision, and Émile Friant (1863-1932). Animal painters like Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899), famous for works such as The Horse Fair, also contributed to the era's focus on rural and natural subjects. Even artists associated with other movements, like Alfred Roll (1846-1919), sometimes tackled large-scale Naturalist scenes of labour.

The interest in rural themes was not confined to France. In Britain, the Newlyn School painters, along with artists like George Clausen (1852-1944) and Herbert Henry La Thangue (1859-1929), were exploring similar subjects, influenced by French Naturalism. Laugée was thus part of a widespread artistic engagement with the realities and perceived virtues of rural life during a period of rapid industrialization and social change.

Personal Life, War, and Later Years

In 1878, Georges Laugée married Eva Jeremine Maliet. The couple had at least one daughter. Family life appears to have been relatively stable, providing a backdrop to his dedicated artistic practice. He maintained studios both in Paris, necessary for engaging with the Salon and the art market, and in the countryside, particularly in Picardy, which allowed him direct access to his primary subjects.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 brought significant disruption and personal loss. Laugée was living in Nauroy (Aisne), a village in Picardy that found itself near the Western Front. This region experienced intense fighting and hardship throughout the war. During this tumultuous period, Laugée suffered the loss of both his parents: his mother passed away in 1914, and his father, Désiré, died in 1916. Despite the difficult circumstances and personal grief, Laugée reportedly continued to paint.

After the war, Laugée seems to have gradually withdrawn from the forefront of the Paris art scene. The artistic landscape was changing rapidly, with modern movements like Fauvism, Cubism, and Surrealism capturing attention. While Realism and Naturalism continued to be practiced, they no longer dominated the avant-garde or official exhibitions as they had in the late nineteenth century.

In his later years, Laugée lived near Paris. He passed away on December 5, 1937, in the Parisian suburb of Passy, at the age of 83. He left behind a substantial body of work documenting the French rural world he knew so intimately.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Georges Laugée's legacy rests on his contribution to French Realist and Naturalist painting. He was a skilled and sensitive chronicler of a way of life that was undergoing profound transformation due to modernization and industrialization. His paintings offered contemporary audiences, and continue to offer viewers today, a connection to the agricultural rhythms and human experiences of the French countryside.

While perhaps not as innovative as the Impressionists or as monumental as Millet, Laugée excelled within his chosen genre. His technical proficiency, combined with his genuine empathy for his subjects and his ability to capture atmospheric light, resulted in works of enduring quality and appeal. His paintings found favour not only with French audiences but also internationally, particularly in the United States, where collectors appreciated French academic and Realist art.

A testament to his broad appeal is the inclusion of his work, such as Milking Time, in popular American educational materials like the Graded Readers series in the early twentieth century. This suggests his paintings were seen as wholesome, instructive, and representative of traditional values, suitable for shaping the views of young people.

Today, Georges Laugée's paintings are held in various museum collections, primarily in France, and appear regularly on the art market, appreciated by collectors of nineteenth-century European art. He remains a respected figure among the painters who dedicated their talents to depicting the dignity of labour and the quiet beauty of the French rural landscape during a pivotal period in the nation's history. His work serves as a valuable visual record and an artistic tribute to the enduring spirit of the French peasant.