Nicholas Alden Brooks (1840-1904) remains a somewhat enigmatic yet significant figure in the landscape of late 19th-century American art. Active primarily in New York City, Brooks carved a distinct niche for himself as a painter of trompe-l'oeil, or "fool the eye," still lifes. His meticulous renderings, particularly of currency, official documents, and ephemeral items like playbills and newspaper clippings, captivated audiences with their uncanny realism and technical finesse. Though his life is not as extensively documented as some of his contemporaries, his surviving works offer a compelling window into his artistic preoccupations and the cultural milieu of his time.

An Obscure Beginning and Artistic Emergence

Details regarding Nicholas Alden Brooks's early life, including his precise birthplace and family background, remain largely unknown to art historians. Similarly, specific information about his formal artistic education or training is scarce. It is widely speculated that he may have been largely self-taught, honing his skills through careful observation and practice, a path not uncommon for artists of that era. What is known is that he was active as an artist in New York City from approximately 1880 until his death in 1904.

Despite his later focus on trompe-l'oeil still life, an early indication of his artistic pursuits includes the exhibition of landscape paintings. Records show that Brooks began exhibiting landscapes at the Brooklyn Art Association as early as 1876. This suggests a broader artistic interest initially, before he specialized in the highly detailed and illusionistic still lifes that would come to define his reputation. His transition towards trompe-l'oeil likely occurred as he recognized his aptitude for meticulous detail and the growing popularity of this genre in America.

The Allure of Deception: Brooks and Trompe-l'oeil

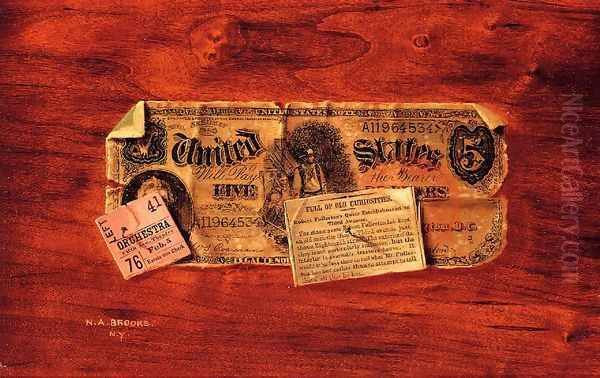

Trompe-l'oeil, a French term meaning "to deceive the eye," is an art technique that uses realistic imagery to create the optical illusion that the depicted objects exist in three dimensions. Brooks excelled in this demanding genre. His compositions typically feature a shallow space, often a wooden board or tabletop, upon which various objects are seemingly tacked, hung, or casually strewn. The power of his work lies in the extraordinary precision with which he rendered textures – the crispness of paper, the grain of wood, the sheen of metal, the subtle wear and tear on aged documents.

His handling of light and shadow was crucial to achieving this illusion. Brooks masterfully manipulated highlights and cast shadows to give his painted objects a tangible presence, making them appear as if they could be lifted directly from the canvas. This meticulous approach demanded immense patience and a keen eye for detail, qualities evident in every brushstroke. His choice of subject matter often revolved around items of everyday life, particularly those associated with commerce, officialdom, and popular entertainment.

Currency and Ephemera: Signature Subjects

One of Brooks's most notable specializations within trompe-l'oeil was the depiction of paper currency. His paintings featuring dollar bills, often rendered with astonishing accuracy, were both a testament to his skill and a reflection of contemporary societal interests. In an era of fluctuating paper money values and concerns about counterfeiting, the hyperrealistic depiction of currency held a particular fascination. These works showcased not only his technical virtuosity but also engaged with themes of value, authenticity, and the very nature of representation.

Beyond currency, Brooks frequently incorporated other ephemeral items into his compositions. Playbills, theater tickets, newspaper clippings, stamps, and calling cards were common motifs. A particularly poignant theme in some of his works relates to President Abraham Lincoln's assassination. He created several pieces featuring playbills from Ford's Theatre for the night of the tragedy, sometimes alongside portraits of Lincoln or other related memorabilia. These works tap into a deep vein of American historical consciousness and demonstrate his ability to imbue still life with narrative and emotional resonance.

Key Works: A Glimpse into Brooks's Oeuvre

Several key works exemplify Nicholas Alden Brooks's artistic style and thematic concerns. His painting Still Life with Books (1890) showcases his ability to render different textures with equal skill. The worn leather bindings of the books, the crisp pages, and perhaps a stray piece of paper or a bookmark are all depicted with the same meticulous attention to detail that characterized his currency paintings. Such works highlight his versatility within the still life genre.

Another exemplary piece is Still Life with Bill, Ticket Stub and Newspaper Clipping. This type of composition is classic Brooks: a collection of everyday items, seemingly casually arranged yet carefully chosen to create a balanced and intriguing visual narrative. The five-dollar bill, rendered with almost photographic precision, would have been a focal point, challenging the viewer to distinguish art from reality. The accompanying ticket stub and fragment of a newspaper add layers of specificity and perhaps hint at a personal or contemporary story. His works often invite close scrutiny, rewarding the viewer with a discovery of minute details.

The Shadow of Harnett: Influence and Misattribution

It is impossible to discuss Nicholas Alden Brooks without mentioning William Michael Harnett (1848-1892), arguably the most famous American trompe-l'oeil painter of the 19th century. Harnett, along with artists like John F. Peto (1854-1907) and John Haberle (1856-1933), formed the core of a significant trompe-l'oeil school in America. Brooks was undoubtedly influenced by Harnett, whose work achieved considerable popularity and critical attention.

The similarities in subject matter (currency, documents, everyday objects) and technique (meticulous realism, shallow depth of field) between Brooks and Harnett were so pronounced that Brooks's works were sometimes misattributed to Harnett. In some instances, it is believed that Harnett's signature was even forged on Brooks's paintings to increase their market value, a testament to Harnett's fame and the convincing quality of Brooks's own work. Despite these overlaps, art historians have since worked to distinguish Brooks's individual hand and contributions, recognizing his unique touch and specific thematic interests, such as his focus on Lincoln memorabilia. While operating within the "Harnett school," Brooks developed his own distinct artistic voice.

Beyond Currency: Other Artistic Pursuits

While trompe-l'oeil paintings of currency and documents form the most recognizable part of his legacy, Brooks's artistic interests were not solely confined to these subjects. As mentioned, he exhibited landscapes early in his career. He also painted other types of still lifes, such as Still Life with Oysters. These works, while perhaps less common than his currency pieces, demonstrate his broader capabilities as a still life painter, adept at capturing the varied textures and forms of different objects, from the glistening, irregular surfaces of oyster shells to the softer forms of fruit or the gleam of silverware.

These forays into other still life subjects underscore his commitment to realism and his fascination with the material world. Each object, whether a humble oyster or a carefully folded banknote, was treated with the same level of intense observation and dedication to accurate representation. This consistent approach across different subjects highlights the underlying principles of his artistic practice.

A Solitary Figure in a Bustling Art World

Interestingly, despite his activity in New York City, a major art center, Nicholas Alden Brooks appears to have been a relatively solitary figure within the formal art establishment. Existing records do not indicate that he was a member of prominent art societies or a frequent participant in major juried exhibitions of the time, beyond his early showings at the Brooklyn Art Association. This contrasts with some of his contemporaries who actively engaged with art organizations to build their careers and reputations.

This apparent detachment from the mainstream art world might suggest a personality inclined towards independent work, or perhaps a focus on a specialized market for his trompe-l'oeil pieces. His works, with their popular appeal and intriguing subject matter, may have found an audience through direct sales or smaller galleries rather than through the large academic exhibitions. Regardless of the reasons, his career path underscores the diverse ways artists navigated the art world in the late 19th century.

The American Still Life Tradition

Nicholas Alden Brooks's work is an important part of the rich tradition of still life painting in America. This tradition dates back to the colonial era, with early practitioners like James Peale (1749-1831) and his nephew Raphaelle Peale (1774-1825), who are considered among the first professional American still life painters. Their work, often characterized by a sober realism and careful arrangement of objects, laid the groundwork for later developments.

Throughout the 19th century, still life painting flourished in various forms. Artists like Severin Roesen (c. 1815-c. 1872) became known for their abundant and opulent fruit and flower still lifes, reflecting Victorian tastes. Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904), though also a renowned landscape painter, produced exquisite still lifes of flowers, often orchids and magnolias, with a unique atmospheric quality. George Henry Hall (1825-1913) was another popular painter of fruit and floral arrangements. The trompe-l'oeil movement, spearheaded by Harnett and including figures like Brooks, Peto, and Haberle, represented a particular, highly illusionistic strand within this broader tradition, one that emphasized verisimilitude and often focused on masculine-coded objects like smoking paraphernalia, hunting gear, books, and money.

The Broader Artistic Landscape of Late 19th-Century America

To fully appreciate Brooks's contribution, it's helpful to consider the wider artistic context of late 19th-century America. This was a period of significant artistic activity and diversification. The Hudson River School, with artists like Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) and Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900), had brought landscape painting to a peak of popularity, celebrating the grandeur of the American wilderness.

Concurrently, realism was a powerful force, championed by figures such as Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) in Philadelphia, known for his unflinching portraits and scenes of modern life, and Winslow Homer (1836-1910), whose depictions of rural America and the sea were both powerful and evocative. American artists were also increasingly engaging with European trends. Many, like Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) and John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), spent significant time abroad, absorbing influences from Impressionism and academic portraiture, respectively. Childe Hassam (1859-1935) became a leading American Impressionist. Brooks's trompe-l'oeil work, with its intense focus on realism, existed alongside these varied movements, offering a distinct, if somewhat specialized, vision.

Artistic Techniques and Innovations

Brooks's technique was characterized by its precision and subtlety. He typically worked with oil paints on canvas or panel, applying thin layers to achieve smooth, almost invisible brushwork, which enhanced the illusion of reality. The compositions were often deceptively simple, yet the arrangement of objects was carefully considered to create a harmonious and believable scene. The shallow depth of field was a hallmark, concentrating the viewer's attention on the objects themselves and their tactile qualities.

His innovation lay not so much in inventing new techniques but in applying existing ones with exceptional skill to his chosen subjects. The convincing depiction of U.S. currency, for example, required an extraordinary level of control and an intimate understanding of the engraving and printing processes of the time. His ability to capture the subtle folds, creases, and worn edges of paper, or the way light reflected off a coin, was remarkable. Some art historians have noted that his sophisticated sense of color and spatial arrangement, though contained within a realist framework, possessed qualities that, in retrospect, seem quite advanced for their time, hinting at a modernist sensibility in their formal abstraction, even if unintended.

Legacy and Reassessment

During his lifetime, Nicholas Alden Brooks achieved a degree of recognition, particularly for his trompe-l'oeil currency paintings. However, like many trompe-l'oeil artists of his generation, his work, and the genre itself, fell somewhat out of favor with the rise of modernism in the early 20th century. The emphasis shifted away from meticulous realism towards more abstract and expressive forms of art.

It was only later, particularly from the mid-20th century onwards, that art historians began to re-evaluate 19th-century American trompe-l'oeil painting. Scholars like Alfred Frankenstein played a crucial role in researching and popularizing artists like Harnett, Peto, and, by extension, figures like Brooks. His work is now appreciated for its technical brilliance, its engagement with American culture and history, and its unique contribution to the still life tradition. His paintings are held in various public and private collections, and they continue to intrigue viewers with their illusionistic power. While initially sometimes overshadowed by Harnett, Brooks is now recognized as a skilled and distinctive artist in his own right. His fascination with the ephemeral, the everyday, and the symbolic power of objects like money and historical documents provides a valuable insight into the American psyche of his era.

Conclusion: An Enduring Illusion

Nicholas Alden Brooks was a dedicated practitioner of a demanding art form. In a period of diverse artistic exploration in America, he chose a path of intense realism, creating works that challenged the viewer's perceptions and celebrated the materiality of the everyday world. His paintings of currency, playbills, and other ephemera are more than just technical exercises; they are cultural artifacts that reflect the values, anxieties, and historical consciousness of late 19th-century America. Though details of his life remain somewhat elusive, his art speaks eloquently of his skill, his patience, and his unique vision. As an art historian, I find his work a compelling example of how meticulous craftsmanship can transform the ordinary into the extraordinary, leaving an enduring legacy of illusion and intrigue.