Richard La Barre Goodwin (1840-1910) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century American art. Born in Albany, New York, Goodwin carved a unique niche for himself, primarily celebrated for his meticulously rendered trompe-l'oeil (French for "deceive the eye") still lifes, particularly those featuring hanging game and the iconic "cabin door" compositions. His work not only showcases exceptional technical skill but also offers a window into the cultural preoccupations and aesthetic tastes of Gilded Age America, a period marked by burgeoning wealth, a nostalgia for the wilderness, and a fascination with illusionistic representation.

Goodwin's artistic journey was shaped by the tumultuous era in which he lived. He served as a soldier during the American Civil War, an experience that, while details of his specific service and injuries remain somewhat fragmented in historical records, undoubtedly impacted his worldview. Following the war, during the Reconstruction era, Goodwin reportedly spent a considerable time as an itinerant artist, traveling and honing his craft. This period of movement likely exposed him to diverse regional tastes and artistic currents, contributing to the development of his distinctive style.

The Allure of Illusion: Goodwin's Trompe-l'oeil Specialization

The late nineteenth century witnessed a flourishing of trompe-l'oeil painting in the United States, and Richard La Barre Goodwin emerged as a notable practitioner within this tradition. This style, which aims to create such convincing illusions of reality that viewers momentarily mistake the painted objects for real ones, had a long history in European art, with masters like Samuel van Hoogstraten in the Dutch Golden Age and later Jean-Étienne Liotard creating astonishing deceptions. In America, the genre found fertile ground, appealing to a public that appreciated technical virtuosity and the playful challenge to perception.

Goodwin’s engagement with trompe-l'oeil was profound. He specialized in compositions that often featured objects associated with masculine pursuits, particularly hunting. His "hanging game" pictures, depicting birds or small animals suspended against a wooden backdrop, were rendered with an almost tactile realism. Feathers would appear soft enough to touch, the textures of wood meticulously detailed, and the interplay of light and shadow would create a powerful sense of three-dimensionality. This focus on verisimilitude was a hallmark of the American trompe-l'oeil school.

A key influence on Goodwin, and indeed on many still life painters of this era, was William Michael Harnett (1848-1892). Harnett was a towering figure in American trompe-l'oeil, and his impact on Goodwin is evident in certain recurring motifs and stylistic choices. For instance, the inclusion of seemingly casually placed, "floating" feathers or the practice of "carving" his signature into the painted wooden surfaces of his compositions are elements that echo Harnett's own work. However, Goodwin was not a mere imitator; he developed his own distinct voice within the genre.

Other prominent artists in this specialized field included John F. Peto (1854-1907), whose works often had a more melancholic and worn quality than Harnett's, and John Haberle (1856-1933), known for his incredibly precise depictions of currency and everyday ephemera. While Goodwin shared their commitment to illusionism, his subject matter, particularly the cabin door paintings, set him apart.

The Cabin Door: A Signature Motif

Perhaps Goodwin's most iconic and enduring contributions to American art are his "cabin door" still lifes. These large-scale paintings typically depict a rustic wooden door, often weathered and textured, upon which are hung an array of objects: hunting rifles, powder horns, game birds, fishing tackle, and sometimes personal mementos. These compositions were more than just technical exercises; they were carefully constructed narratives that evoked a romanticized vision of the American outdoorsman and the frontier spirit.

The door itself becomes a stage, a shallow space where objects are arranged to maximize their illusionistic impact. Goodwin's skill in rendering different textures – the rough grain of wood, the metallic sheen of a gun barrel, the soft plumage of a bird – was paramount. He employed subtle shadowing and precise highlights to make objects appear to project from the canvas, creating a compelling sense of depth and presence. This technique, pushing the boundaries of two-dimensional representation, was central to the appeal of his work.

These paintings resonated deeply with the cultural climate of the time. The late 19th century saw rapid industrialization and urbanization, leading to a concurrent wave of nostalgia for a perceived simpler, more rugged past. Figures like Theodore Roosevelt, himself an avid outdoorsman and conservationist, championed the "strenuous life," and Goodwin's cabin door paintings tapped into this prevailing ethos. They celebrated self-reliance, the connection to nature, and a distinctly American masculine identity.

Notable Works and Their Significance

Several of Richard La Barre Goodwin's paintings stand out for their artistic merit and cultural resonance. Among his most celebrated is Theodore Roosevelt's Cabin Door (1905). This work is a quintessential example of his cabin door series, depicting a rich assortment of hunting paraphernalia against a wooden backdrop. The title itself links the painting to a powerful national figure, further cementing its connection to the era's idealization of the outdoors. The painting is often interpreted as an idealized depiction of American society and its values in the post-Civil War era, reflecting a sense of order and rugged individualism.

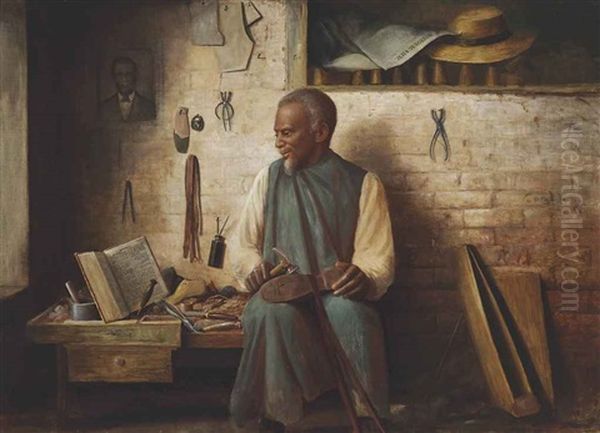

Another significant piece is The Cobbler (1897). While not a cabin door painting, it showcases Goodwin's versatility and his engagement with social themes. The work portrays an African American shoemaker in his workshop. Art historians have noted the painting's complex layering of meaning, potentially incorporating biblical allusions (perhaps to the idea that "these dead men shall not perish," referencing Revelation, in the context of post-Civil War reconciliation and resilience) and political symbolism. It reflects an idealized view of American society after the Civil War, highlighting craftsmanship and dignity. This work demonstrates Goodwin's ability to imbue his realistic depictions with deeper narrative and symbolic content, moving beyond mere technical display.

After the Hunt (1902) is another exemplary work, showcasing his mastery in depicting hanging game. The meticulous rendering of feathers, the subtle variations in color, and the convincing illusion of weight and volume are all hallmarks of Goodwin's skill. Such paintings appealed to a clientele that often included sportsmen and those who admired the traditions of the hunt. These works found a place in men's clubs, lodges, and private homes, serving as visual trophies and reminders of the natural world. The precision in these works can be compared to the detailed wildlife studies of artists like John James Audubon, though Goodwin's focus was on the trompe-l'oeil presentation of game as still life.

Goodwin's approach to still life, while rooted in the tradition of artists like the Peale family (Charles Willson Peale, Raphaelle Peale, James Peale), who were pioneers of American still life painting, pushed the boundaries of illusionism in ways that were distinctly of his time. His work, like that of Harnett and Peto, often focused on masculine objects and settings, a departure from the more delicate floral and fruit still lifes often associated with earlier periods or with female artists of his own time.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Influences

Richard La Barre Goodwin's artistic style is primarily characterized by its meticulous realism and its embrace of trompe-l'oeil techniques. He possessed an extraordinary ability to replicate the appearance of various materials and textures, from the rough grain of aged wood to the soft down of a bird's feather or the cold gleam of metal. This verisimilitude was achieved through careful observation, precise draftsmanship, and a sophisticated understanding of light and shadow.

His compositions, particularly the cabin door paintings, are often characterized by a shallow depth of field, with objects arranged in a relatively flat plane against a background surface. This compositional strategy enhances the illusionistic effect, as it minimizes perspectival complexities and focuses the viewer's attention on the tactile qualities of the depicted items. The use of cast shadows was crucial, making objects appear to lift off the surface or recede slightly, thereby creating a convincing, albeit limited, three-dimensional space.

Goodwin often employed a palette of earthy tones – browns, ochres, grays, and muted greens – which contributed to the rustic and often nostalgic atmosphere of his paintings. These colors were well-suited to his subject matter of weathered wood, leather, and game. However, he was also capable of introducing brighter accents where appropriate, such as the vibrant plumage of a bird or the glint of a brass fitting.

The influence of William Michael Harnett is undeniable, particularly in the choice of subject matter (pipes, books, hunting gear) and specific illusionistic devices. However, Goodwin's work often possesses a slightly different sensibility. While Harnett's arrangements could sometimes feel more formal or even cluttered, Goodwin's cabin door compositions often have a sense of curated order, as if presenting an idealized inventory of the outdoorsman's life.

Beyond the immediate circle of trompe-l'oeil specialists, Goodwin's work can be situated within the broader context of American Realism, a movement that included towering figures like Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer. While Eakins focused on the human figure and portraiture with an unflinching psychological depth, and Homer captured the raw power of nature and human interaction with it, Goodwin's realism was channeled into the intimate and deceptive world of still life. His dedication to depicting the "real" was shared, even if his chosen arena was different.

The romantic element in Goodwin's work, particularly the evocation of a rugged, independent lifestyle, also connects him to some of the sentiments found in the landscape paintings of the Hudson River School artists like Albert Bierstadt or Thomas Moran, though their grand vistas are a world away from Goodwin's focused still lifes. The common thread is a fascination with the American landscape and the character it was believed to forge.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Later Career

Throughout his career, Richard La Barre Goodwin exhibited his work at various prestigious institutions, gaining recognition for his unique talents. He was a member of the Boston Art Club and showcased his paintings there. His work was also seen at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where he participated in an exhibition in 1911, shortly after his death, alongside many prominent Boston artists. This indicates his standing within the artistic community of the time.

Other notable venues where Goodwin's art was displayed include the St. Botolph Club in Boston, Vose Galleries (which held solo exhibitions of his work posthumously in 1920, and later in 1985 and 1988, signaling a revival of interest), the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh. He also exhibited with the American Institute of Art. The inclusion of his work, such as After the Hunt, in private collections like the Nancy and Sean Cotton Collection, further attests to its desirability and enduring appeal.

Despite this recognition, details about Goodwin's formal art education remain somewhat elusive in comprehensive art historical records. Many artists of his generation received training in academies either in the United States or abroad, or apprenticed with established painters. It is plausible that Goodwin's skills were honed through a combination of such experiences and his own dedicated practice, particularly during his time as an itinerant artist. The technical proficiency evident in his work suggests a rigorous, if not formally documented, artistic training.

His later career saw him continue to produce the cabin door and hanging game still lifes for which he was known. He lived and worked in various cities, including Syracuse, New York; Washington D.C.; Chicago; and Orange, New Jersey, before passing away in 1910.

Academic Evaluation and Lasting Legacy

In the broader sweep of art history, Richard La Barre Goodwin is recognized as a significant contributor to the American trompe-l'oeil movement. His work is often discussed alongside that of Harnett, Peto, and Haberle, forming a core group of artists who brought this illusionistic style to a high degree of perfection and popularity in the United States. Academic assessments highlight his technical mastery, his distinctive cabin door motif, and the way his paintings captured certain cultural ideals of his era.

His art is seen by some scholars as occupying a fascinating space between straightforward American Realism and a more enigmatic, almost proto-Surrealist sensibility, particularly in the way his hyper-realistic depictions can create an unsettling or dreamlike effect. The very act of meticulously recreating reality to deceive the eye touches upon philosophical questions about perception and representation, themes that would be explored more explicitly by later movements like Surrealism, with artists such as René Magritte famously playing with words and images to challenge viewers' assumptions about reality.

Goodwin's influence on subsequent artists might be less direct than that of some of his more avant-garde contemporaries, but his contribution to the tradition of American still life is secure. His paintings continue to be admired for their craftsmanship and their evocative power. They serve as important documents of a particular period in American history, reflecting its tastes, its anxieties, and its aspirations. The enduring appeal of trompe-l'oeil ensures that Goodwin's work remains fascinating to audiences today, who marvel at his ability to blur the line between the painted world and our own.

The study of Goodwin's oeuvre also sheds light on the art market and patronage of the Gilded Age. His works, with their accessible subject matter and impressive technical skill, found a ready audience among a growing class of affluent Americans who sought art that was both aesthetically pleasing and reflective of their values. Artists like William Merritt Chase, a contemporary known for his sophisticated portraits and impressionistic scenes, catered to a similar clientele, though with a vastly different style.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of American Still Life

Richard La Barre Goodwin was an artist who, through dedication and remarkable skill, mastered a challenging and captivating genre. His hanging game and cabin door still lifes are more than mere technical marvels; they are cultural artifacts that speak to the ideals and aesthetics of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century America. Influenced by masters like William Michael Harnett, yet developing his own unique voice, Goodwin created a body of work that continues to engage and deceive the eye.

His paintings, such as Theodore Roosevelt's Cabin Door and The Cobbler, demonstrate a keen observational power and an ability to imbue everyday objects with narrative and symbolic weight. While the grand historical narratives were being painted by some, and the stirrings of modernism were beginning to be felt with artists like Alfred Maurer or John Marin (though their major impact came slightly later), Goodwin and his fellow trompe-l'oeil painters offered a different kind of artistic experience – one rooted in meticulous realism, playful illusion, and a deep appreciation for the tangible world. His legacy is that of a dedicated craftsman and a keen observer, an artist who left an indelible mark on the tradition of American still life painting.