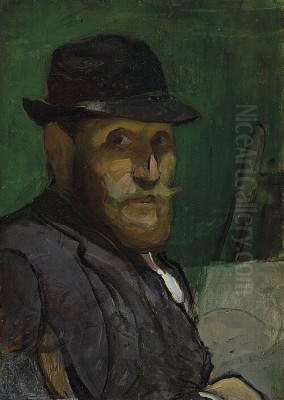

Louis Anquetin stands as a fascinating, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. Born in Étrépagny, France, on January 26, 1861, and passing away in Paris on August 19, 1932, Anquetin's life spanned a period of radical artistic transformation. He was not merely a witness to these changes but an active participant, contributing significantly to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, most notably through his co-creation of Cloisonnism, before embarking on a later, surprising return to the aesthetics of the Old Masters. His journey reflects the era's dynamic experimentation and the complex relationship artists had with tradition and modernity.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Louis Anquetin hailed from a background of relative comfort; his father was a prosperous butcher in Étrépagny. This supportive environment allowed his artistic inclinations to be nurtured from a young age. His formal education included attendance at the Lycée Pierre Corneille in Rouen, from which he graduated in 1880. Driven by his passion for art, Anquetin made the pivotal move to Paris in 1882, the undisputed center of the art world at the time.

His initial training took place in the studio of Léon Bonnat, a respected academic painter. However, Anquetin soon moved to the more progressive atelier of Fernand Cormon. Cormon's studio was a crucible of emerging talent, and it was here that Anquetin formed crucial friendships that would shape his early career. He became close associates with fellow students who would achieve immense fame: the distinctive Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, the intellectually driven Émile Bernard, and the intensely passionate Vincent van Gogh. This environment fostered a spirit of collaboration, debate, and shared exploration of new artistic paths.

The Innovation of Cloisonnism

The mid-1880s were a period of intense artistic ferment in Paris. Impressionism, while established, was already being challenged and expanded upon by a younger generation. Within Cormon's studio and the broader Parisian art scene, Anquetin and his friend Émile Bernard engaged in deep discussions and experiments aimed at moving beyond the Impressionist focus on fleeting light effects. They sought a style that emphasized strong forms and bold colors, drawing inspiration from unconventional sources.

Together, Anquetin and Bernard developed a new artistic approach they termed "Cloisonnism." This style was characterized by areas of flat, unmodulated color separated by thick, dark outlines, reminiscent of the lead Cames used in medieval stained-glass windows (cloisonné in French refers to partitioned enamelwork). Another significant influence was the Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints, admired for their flattened perspectives, decorative compositions, and bold contours. Cloisonnism represented a deliberate move away from Impressionist naturalism towards a more synthetic and symbolic representation.

Anquetin's painting Avenue de Clichy: Five O'Clock in the Evening (1887) is arguably the most iconic example of early Cloisonnism. This work, depicting a Parisian street scene under the artificial glow of gaslight, captures the specific atmosphere of the modern city. Anquetin used strong blue tones outlined in dark contours for the figures and background, contrasting them with the yellow radiance of the shopfront light. The painting’s bold simplification and expressive color caught the attention of contemporaries, including Vincent van Gogh, who was deeply impressed by Anquetin's ability to capture the nocturnal mood.

The development of Cloisonnism was a collaborative effort, and Paul Gauguin, another major figure of Post-Impressionism, quickly became associated with the style, adapting its principles in his own distinctive works created in Pont-Aven. While debates sometimes arose about the precise origins and contributions, it's clear that Anquetin and Bernard were central figures in its initial formulation around 1886-1887, exploring its potential through mutual influence and shared artistic goals. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, though perhaps not a co-inventor, was certainly influenced by the style, incorporating its flattened forms and strong lines into his own depictions of Parisian nightlife.

Engagement with the Avant-Garde and Parisian Scenes

Through the late 1880s and early 1890s, Anquetin was an active participant in the Parisian avant-garde. His innovative Cloisonnist works positioned him as a key figure within Post-Impressionism. He exhibited his paintings at important venues that showcased new art, including the Salon des Indépendants in Paris and the progressive Les XX exhibition in Brussels in 1888. His participation in the 1889 Paris International Exposition brought him wider recognition and, significantly, a degree of financial independence.

A major solo exhibition at the Salon des Indépendants in 1891 further cemented his reputation. He presented ten significant works, including the striking Woman on the Champs-Elysées by Night, showcasing his mastery of the Cloisonnist style and his fascination with the modern urban experience, particularly the allure and mystery of Paris after dark. His paintings often featured scenes of cafes, boulevards, and racetracks, capturing the energy and specific light conditions of the city. Works like Les Chambres (Bedroom Scenes) explored more intimate interior settings, but still often employed the bold outlines and color fields characteristic of his style during this period.

His interactions with fellow artists remained crucial. The mutual respect and artistic dialogue with Van Gogh are well-documented. Anquetin's bold use of color and form undoubtedly resonated with Van Gogh, while some have noted potential influences from Van Gogh's work, such as The Night Café, on Anquetin's nocturnal themes, though Anquetin's Cloisonnist approach remained distinct. His close friendship with Toulouse-Lautrec continued, marked by shared interests in depicting modern life and a mutual exploration of expressive line and form. He was also connected to the broader circle of Post-Impressionist artists, including figures like Paul Cézanne, whose structural approach to painting was revolutionizing art, although Anquetin's path diverged significantly from Cézanne's.

The Pivotal Journey and Stylistic Shift

Despite his success and recognition within the avant-garde, Anquetin's artistic direction took a dramatic turn in the mid-1890s. A key catalyst for this change was a trip he undertook in 1893 with his friend Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec to Belgium and the Netherlands. The purpose of this journey was specifically to study the works of the Old Masters. They immersed themselves in the paintings of Flemish and Dutch giants like Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, Frans Hals, and Rembrandt van Rijn.

This direct encounter with the technical mastery, dramatic power, and rich textures of Baroque painting had a profound impact on Anquetin. He reportedly felt that his own modern works, in comparison, seemed "obscure and laborious." He began to question the direction of contemporary art and felt a growing disillusionment with the avant-garde path he had been pursuing. The trip solidified a conviction that the techniques and artistic depth of the Old Masters held enduring value that had perhaps been neglected by modern painters.

This experience led Anquetin to make a conscious and decisive break from modernism. He resolved to abandon the Cloisonnist style and dedicate himself to studying and mastering the techniques of the painters he had admired on his travels. This wasn't merely a superficial imitation but a deep dive into understanding their methods of composition, color handling, and paint application. Further reinforcing this shift, Anquetin is known to have discussed technical matters, such as pigments and materials, with the Impressionist master Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who himself possessed a deep respect for classical traditions.

Later Career: Embracing the Masters

From the mid-1890s onwards, Anquetin's art underwent a radical transformation. He largely abandoned the flat colors and bold outlines of Cloisonnism, turning instead towards a style deeply indebted to the Baroque, particularly the work of Peter Paul Rubens. His paintings became more dynamic, featuring swirling compositions, dramatic lighting, and a richer, more painterly application of pigment. He increasingly focused on large-scale allegorical, mythological, and historical subjects, themes favored by the Old Masters he now emulated.

This shift was not universally understood or accepted by the avant-garde circles he had previously frequented. To some, it seemed like a regression, a turning away from the progressive spirit of modern art. However, for Anquetin, it represented a path towards greater artistic depth and technical proficiency. He dedicated himself to studying the materials and methods of painters like Rubens, seeking to recapture their vibrancy and power.

His commitment to this new direction was evident in major commissions, such as the large murals he painted for the Town Hall of Thouars in 1901. These works clearly demonstrated his engagement with Baroque compositional strategies and allegorical content. His deep admiration for Rubens culminated in the publication of his book, simply titled Rubens, in 1924. This publication was both an homage and a scholarly exploration of the Flemish master's art and techniques.

Beyond his own painting, Anquetin became increasingly involved in art education during his later years. He lectured on painting techniques, particularly those of the Old Masters, at institutions like the Université Populaire (People's University). He guided students in the study of various painting materials, pigments, and historical methods, sharing the knowledge he had painstakingly acquired. His personal life during this period was relatively quiet; he lived with his wife, Berthe Coquinot, and continued his artistic pursuits and research until his death in Paris in 1932.

Legacy and Rediscovery

Louis Anquetin's artistic legacy is complex. For a significant period, his later shift towards classical styles led to him being somewhat marginalized in standard art historical narratives, which often prioritize the linear progression of modernism. His early contributions, particularly the co-invention of Cloisonnism, were sometimes overshadowed by the greater fame of contemporaries like Gauguin or Van Gogh. The very stylistic shifts that defined his career made him difficult to categorize, potentially contributing to his relative neglect. Furthermore, his later Rubenesque works, while technically accomplished, were out of step with the dominant trends of Fauvism, Cubism, and subsequent modernist movements championed by artists like Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, even though some argue his early work had an influence on these very figures.

However, in more recent decades, there has been a growing reassessment of Anquetin's career. Art historians now recognize the crucial role he played in the development of Post-Impressionism and Cloisonnism. His Avenue de Clichy is acknowledged as a landmark work that anticipated aspects of Expressionism and Fauvism in its bold, non-naturalistic use of color and line. His willingness to engage deeply with both Japanese prints and European Old Masters demonstrates a breadth of artistic curiosity.

His later career, once dismissed as reactionary, is now viewed with more nuance. It reflects a genuine, albeit unconventional, search for artistic meaning and technical mastery. His dedication to studying and reviving Old Master techniques, while isolating him from the contemporary avant-garde, contributed to a continued dialogue about the relationship between tradition and innovation in art. His teaching and writings, particularly the book on Rubens, also represent a valuable contribution to the understanding of historical painting practices.

While perhaps not achieving the household-name status of Van Gogh, Gauguin, or Toulouse-Lautrec, Louis Anquetin remains an important artist. His journey from the Impressionist-influenced environment of Cormon's studio, through the radical innovation of Cloisonnism, to a deep engagement with the Baroque masters, offers a unique perspective on the artistic possibilities and intellectual currents of his time. He was an artist who dared to forge his own path, even when it led him away from the prevailing trends, leaving behind a body of work that continues to intrigue and reward study. His career serves as a reminder that artistic development is not always linear and that engagement with the past can be as radical as the pursuit of the new.