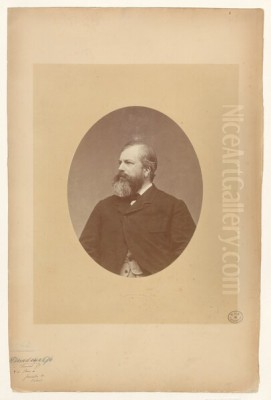

Louis Devedeux stands as a notable figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art, particularly within the captivating genre of Orientalism. Born in Clermont-Ferrand on July 8, 1820, and passing away in Paris in 1874, Devedeux carved a niche for himself as a history painter whose canvases predominantly transported viewers to idealized and romanticized visions of the East. Though he never personally ventured to the lands he so vividly depicted, his work resonated with the European fascination for distant cultures, contributing significantly to the visual lexicon of Orientalist art. His artistic journey was shaped by esteemed masters and, in turn, he influenced others, leaving behind a legacy of works that continue to intrigue and delight.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

The foundations of Louis Devedeux's artistic career were laid under the tutelage of two of the most respected academic painters of his time: Paul Delaroche and Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps. This education was pivotal, instilling in him the technical proficiency and thematic inclinations that would define his oeuvre. Clermont-Ferrand, his birthplace, provided the initial backdrop to his life, but it was in the artistic crucible of Paris that his talents would be honed.

Paul Delaroche (1797-1856) was a towering figure in French academic art, renowned for his meticulously rendered historical scenes, often imbued with a sense of drama and pathos. Works like The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833) and Bonaparte Crossing the Alps (1848) exemplified his commitment to historical accuracy in detail, combined with a flair for theatrical composition. From Delaroche, Devedeux likely absorbed a rigorous approach to figure painting, an understanding of narrative construction within a composition, and a respect for the grand tradition of history painting. Delaroche's own studio was a hub for aspiring artists, and his influence extended to a generation of painters who sought to capture pivotal historical moments with precision and emotional depth.

Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps (1803-1860), on the other hand, was one of the pioneering French Orientalists. Unlike many of his contemporaries who imagined the East from afar, Decamps had traveled, notably to Turkey and Asia Minor in the late 1820s. His experiences lent an air of authenticity, or at least a more direct observational quality, to his depictions of everyday life, landscapes, and historical scenes set in the Ottoman Empire. Works such as The Turkish Patrol (c. 1830-31) showcased his ability to capture the atmosphere, light, and character of the regions he visited. Decamps' influence on Devedeux would have been profound, steering him towards Orientalist themes and perhaps inspiring his rich color palettes and attention to exotic detail, even if Devedeux’s Orient was one filtered through imagination and existing visual tropes rather than direct experience.

This dual mentorship provided Devedeux with a versatile skill set: the historical gravitas and compositional discipline of Delaroche, combined with the thematic allure and atmospheric richness championed by Decamps. It was a potent combination that equipped him to navigate the Parisian art world and make his mark within the burgeoning Orientalist movement.

The Allure of the Orient: Contextualizing Orientalism

The 19th century witnessed an explosion of European interest in the "Orient"—a term then used broadly to encompass North Africa, the Middle East, and sometimes even parts of Asia. This fascination was fueled by a confluence of factors: Napoleon Bonaparte's Egyptian campaign (1798-1801) opened up new vistas, Romanticism fostered a yearning for the exotic and the sublime, and expanding colonial enterprises brought European powers into closer, albeit often fraught, contact with these regions. Literature, travelogues, and, crucially, visual art played a significant role in shaping European perceptions of these distant lands.

Artists were drawn to the perceived sensuality, vibrant colors, different customs, and dramatic landscapes of the East. Early proponents like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, with his iconic La Grande Odalisque (1814), explored Orientalist themes from a classical, studio-based perspective, focusing on the exoticism of the female form in imagined harem settings. Eugène Delacroix, profoundly impacted by his 1832 trip to Morocco and Algeria, brought a Romantic fervor and a more direct, though still interpreted, observation to works like Women of Algiers in their Apartment (1834) and The Death of Sardanapalus (1827), the latter a grand, violent fantasy.

By the mid-19th century, when Devedeux was establishing his career, Orientalism had become a well-established and popular genre. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, a contemporary of Devedeux and also a student of Delaroche, became immensely successful with highly detailed, almost photographically precise (though often staged) depictions of Middle Eastern life, such as The Snake Charmer (c. 1879) and The Slave Market (c. 1866). Théodore Chassériau, another contemporary, blended Ingres's classicism with Delacroix's romanticism in his Orientalist works. The public appetite for these scenes was immense, and the Paris Salon regularly featured a plethora of paintings depicting bustling souks, serene mosques, languid odalisques, and fierce warriors.

It was within this vibrant and competitive artistic landscape that Louis Devedeux developed his own particular vision of the East. He belonged to what some art historians term the "second wave" of Orientalist painters, artists who built upon the foundations laid by pioneers like Delacroix and Decamps, often catering to a market eager for accessible and picturesque representations of these far-off lands.

Devedeux's Orientalist Vision: An Imagined East

A defining characteristic of Louis Devedeux's Orientalism was that it was largely a product of his imagination, informed by the works of other artists, literary accounts, and the prevailing European stereotypes and fantasies about the East. He did not undertake the arduous and often dangerous journeys to North Africa or the Levant that some of his contemporaries, like Eugène Fromentin, Léon Belly, or Gustave Guillaumet, did. Instead, Devedeux constructed his Orient within the confines of his Paris studio, relying on props, models, and a rich visual vocabulary derived from existing Orientalist art.

His paintings often focused on intimate, idealized scenes, particularly those involving women in domestic or harem settings. These depictions catered to a Western male gaze that often projected sensuality and languor onto Eastern women. Themes of the harem, with its connotations of mystery, luxury, and eroticism, were popular. Devedeux also painted scenes of daily life, such as merchants in marketplaces, children at play, and moments of quiet contemplation. His works are characterized by a careful attention to detail in costume, textiles, and architectural elements, all rendered with a polished technique.

The colors in Devedeux's paintings are typically rich and harmonious, contributing to the overall sense of opulence and exoticism. He skillfully manipulated light and shadow to create atmosphere and highlight the textures of silks, velvets, and intricate metalwork. While his scenes might lack the ethnographic accuracy or raw immediacy of artists who had traveled extensively, they possess a dreamlike quality, offering a romantic escape for the European viewer. His Orient was a place of beauty, leisure, and sometimes gentle melancholy, largely devoid of the harsher realities or complexities of the regions he depicted.

Key Works and Their Characteristics

Louis Devedeux's body of work includes several paintings that exemplify his style and thematic concerns. These pieces showcase his technical skill, his imaginative approach to Orientalist subjects, and his ability to create engaging narrative vignettes.

Les marchands arabes (Arab Merchants) is a fine example of his marketplace scenes. Measuring 57 x 81 cm and executed in oil, this painting likely depicts a bustling commercial interaction, a common trope in Orientalist art that allowed for the portrayal of diverse characters, colorful goods, and exotic settings. The presence of a gallery stamp suggests its circulation and recognition within the art market of the time. Such scenes provided a window into the perceived vibrancy and commercial energy of Eastern cities.

Jeune Femme et sa Maiden (Young Woman and Her Maid), also known as Jeune Femme et sa Servante, dated to 1856 and measuring 36 x 55 cm, delves into the popular theme of women in domestic interiors. This subject allowed Devedeux to explore textures of fabrics, the play of light on skin and jewelry, and the intimate dynamics between figures. The relationship between a mistress and her attendant was a recurring motif, often imbued with a sense of quietude or subtle narrative.

Farewell Before the Combat, a work measuring 67 x 42.5 cm, introduces a more dramatic element. While still set within an Orientalist framework, the theme of departure for battle hints at narratives of love, honor, and conflict. Such paintings appealed to the Romantic sensibility for heightened emotion and picturesque heroism, transposed to an exotic locale. The costumes and weaponry would have been rendered with Devedeux's characteristic attention to detail, enhancing the scene's visual appeal.

The Pride of the Harem is another significant work that encapsulates many of Devedeux's preoccupations. Descriptions of this painting evoke a scene of leisurely opulence: a young woman in a white dancing dress plays a mandolin on a sofa, surrounded by four young girls scattering flowers, while a slave attends with a tray. This composition is a quintessential Orientalist fantasy, combining music, youthful beauty, servitude, and an atmosphere of secluded luxury. It speaks directly to the Western fascination with the imagined sensuality and mystery of the harem.

These works, among others, demonstrate Devedeux's consistent engagement with the popular tropes of Orientalism. He skillfully blended figurative painting with detailed settings, creating compositions that were both visually appealing and narratively suggestive. His paintings offered viewers an escape into a world that, while not necessarily authentic, was undeniably captivating.

Beyond the Harem: Historical Subjects

While primarily known for his Orientalist genre scenes, Louis Devedeux also engaged with historical subjects, a testament to his training under Paul Delaroche. His interest in history painting extended to depicting significant figures and events, sometimes with an Orientalist inflection.

One notable example is his painting of Napoléon dans le désert (Napoleon in the Desert). This work, measuring 93 x 133 cm, was significant enough to be sold at auction in 1875, the year after his death. The subject of Napoleon in Egypt was a potent one, merging French national pride with the allure of the Orient. It allowed Devedeux to combine his skills in historical representation with the exotic landscapes and atmospheres that characterized his Orientalist work. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme also famously depicted Napoleon in Egypt (e.g., Bonaparte Before the Sphinx), highlighting the enduring appeal of this historical episode.

Another work, Napoléon au défilé de Suez (Napoleon at the Suez Pass/Strait), further underscores his engagement with Napoleonic themes set against an Eastern backdrop. These paintings would have required a different kind of research and compositional approach than his more intimate genre scenes, focusing on historical figures, military attire, and grander narratives. They demonstrate Devedeux's versatility and his ambition to tackle subjects beyond the confines of the harem or the marketplace.

His involvement in history painting connected him to a long and prestigious tradition in French art, and his choice to sometimes set these historical narratives in the East allowed him to leverage his established reputation as an Orientalist painter. This blending of genres likely broadened his appeal and showcased the breadth of his artistic capabilities.

Technique, Style, and Artistic Signature

Louis Devedeux's artistic style was characterized by a polished academic finish, a legacy of his training with Delaroche. His brushwork was generally smooth and controlled, allowing for a high degree of detail and a refined surface quality. This meticulousness was particularly evident in his rendering of fabrics, architectural details, and human anatomy. He paid close attention to the textures of silk, velvet, carpets, and inlaid mother-of-pearl, contributing to the tactile richness of his scenes.

His color palette was typically warm and vibrant, employing jewel-like tones to evoke the perceived opulence of the East. Deep reds, blues, greens, and golds often feature prominently, creating a sense of luxury and visual splendor. He was adept at using light to create mood and highlight focal points within his compositions. Soft, diffused light often bathes his interior scenes, enhancing their intimacy, while brighter, more direct light might be used in outdoor or more dramatic settings.

Compositionally, Devedeux's paintings are generally well-balanced and clearly organized. Figures are often arranged in a theatrical manner, guiding the viewer's eye through the narrative. He frequently employed a pyramidal or triangular compositional structure, a classical device that lends stability and harmony to the scene. His figures, while idealized, are rendered with anatomical correctness and expressive gestures, conveying emotion and character.

While he may not have been an innovator in the same vein as Delacroix or a meticulous ethnographer like some later Orientalists, Devedeux's strength lay in his ability to synthesize existing Orientalist tropes into appealing and technically accomplished images. His work represents a particular strand of Orientalism that prioritized aesthetic pleasure and romantic fantasy over strict authenticity or challenging social commentary. He was a skilled storyteller in paint, creating accessible and engaging visions of a distant, imagined world.

Influence and Legacy

Louis Devedeux's impact on the art world can be seen both in his contributions to the Orientalist genre and in his role as an educator. His paintings were part of the vast visual culture that shaped 19th-century European perceptions of the East, contributing to the popularity and persistence of Orientalist themes. His works found their way into collections, including, as noted, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Archives du Mobilier National, indicating a level of contemporary recognition and esteem.

One of his most notable students was the French painter Louise Abbéma (1853-1927). Abbéma, who also studied with Charles Chaplin and Jean-Jacques Henner, went on to have a successful career, becoming known for her portraits, genre scenes, and decorative panels, often featuring elegant women and floral motifs. Her association with Devedeux suggests that his studio was a place where aspiring artists could receive instruction in the academic tradition. Abbéma's later success, particularly her portraits of Sarah Bernhardt, brought her considerable fame.

Devedeux's contemporaries in the Orientalist field were numerous and varied. Beyond his teacher Decamps and the highly influential Gérôme, artists like Eugène Fromentin (1820-1876) offered a more literary and nuanced perspective on North Africa, based on his travels and writings. Léon Belly (1827-1877) was acclaimed for his detailed Egyptian landscapes and scenes, such as Pilgrims Going to Mecca. Gustave Guillaumet (1840-1887) dedicated his career to depicting the landscapes and people of Algeria with a sense of empathy and realism.

Other prominent Orientalists of the era included Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant (1845-1902), known for his large-scale, dramatic scenes of Moroccan life and harems; the Austrian painters Ludwig Deutsch (1855-1935) and Rudolf Ernst (1854-1932), who became famous for their hyper-realistic and minutely detailed depictions of Cairo street scenes, scholars, and guards; and the American Frederick Arthur Bridgman (1847-1928), a student of Gérôme who also traveled extensively in North Africa. Italian artists like Alberto Pasini (1826-1899) and Spanish painters like Mariano Fortuny (1838-1874) also made significant contributions to the genre, each bringing their own cultural perspectives and stylistic innovations. The British painter John Frederick Lewis (1804-1876) spent a decade living in Cairo and produced incredibly detailed watercolors and oils of Middle Eastern life.

Within this diverse and crowded field, Devedeux occupied a specific niche. He was not a traveler-ethnographer nor a radical innovator, but a skilled academic painter who successfully adapted his talents to a popular and lucrative genre. His legacy lies in his contribution to the visual tapestry of 19th-century Orientalism, creating works that satisfied the public's desire for romantic and picturesque visions of the East.

Critical Reception and Modern Perspectives

During his lifetime, Louis Devedeux's work would have been received within the context of the prevailing tastes of the Paris Salon and the broader art market. The popularity of Orientalist themes ensured a receptive audience for painters specializing in this genre. His technical skill and the appealing nature of his subjects likely garnered positive attention. The sale of his Napoleon in the Desert posthumously in 1875 suggests that his works retained value and interest.

In more recent times, the entire genre of Orientalism has been subject to critical re-evaluation, most notably influenced by Edward Said's seminal 1978 book, Orientalism. Said argued that Western depictions of the East were often based on stereotypes and fantasies that served to reinforce colonial power structures and a sense of Western superiority. This critique has led to a more nuanced understanding of Orientalist art, acknowledging its aesthetic qualities while also considering its historical and cultural implications.

From this perspective, Devedeux's work, like that of many of his contemporaries, can be seen as participating in the construction of a particular Western "idea" of the Orient. His idealized harems, picturesque markets, and romanticized figures, while visually charming, often perpetuated certain clichés. The fact that he never traveled to the East further underscores the imaginative, rather than observational, basis of his depictions.

However, to dismiss Orientalist art solely on these grounds would be to overlook its artistic merits and its significance within 19th-century culture. These paintings are valuable historical documents, reflecting the preoccupations, desires, and anxieties of their time. Devedeux's art, with its polished technique and romantic sensibility, offers a window into this complex cultural phenomenon. His works continue to be appreciated for their craftsmanship, their evocative power, and their contribution to a fascinating chapter in the history of art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of the Imagined East

Louis Devedeux was a product of his time, an artist who skillfully navigated the currents of 19th-century French academic art and the immense popularity of Orientalist themes. Trained by masters like Paul Delaroche and Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, he developed a distinctive style characterized by technical polish, rich color, and a romantic sensibility. His idealized depictions of harem interiors, bustling marketplaces, and historical scenes set in the East captivated contemporary audiences and contributed to the enduring visual allure of the Orient in Western imagination.

Though he never set foot in the lands he painted, Devedeux's canvases created a compelling, if fantasized, world that resonated with the escapist desires of his viewers. His representative works, such as Les marchands arabes, Jeune Femme et sa Maiden, and The Pride of the Harem, showcase his ability to craft intricate and engaging narratives within an exotic framework. His historical paintings, particularly those featuring Napoleon in Egypt, further demonstrate his versatility.

As a teacher, he influenced artists like Louise Abbéma, and his works found their place alongside those of numerous other distinguished Orientalist painters, including Jean-Léon Gérôme, Eugène Fromentin, and Ludwig Deutsch, each contributing to the multifaceted genre. While modern perspectives invite a critical understanding of Orientalism's cultural implications, Louis Devedeux's art remains a testament to the imaginative power of painting and the enduring human fascination with distant worlds. His legacy is that of a dedicated craftsman and a vivid chronicler of the 19th century's romantic engagement with the East.