Louis-Félix Delarue, a notable yet often under-discussed figure in the vibrant tapestry of eighteenth-century French art, navigated the worlds of sculpture, painting, and decorative design with a distinct Rococo sensibility. Born in Paris in 1730 or 1731, his life, though relatively short as he passed away in 1765, coincided with a period of immense artistic flourishing in France. This era, characterized by the playful elegance of the Rococo style and the burgeoning intellectual currents of the Enlightenment, provided a fertile ground for artists who could blend technical skill with imaginative grace. Delarue, though perhaps not achieving the towering fame of some of his contemporaries, carved out a niche for himself through his refined drawings, spirited sculptures, and intricate designs for decorative objects.

His artistic journey was shaped by his familial connections and formal training. He was the elder brother of Philibert Benoît de Larue (1718–1780), himself an accomplished painter and engraver, suggesting an early immersion in an artistic environment. This familial background likely fostered his initial artistic inclinations, leading him to pursue formal studies.

Artistic Formation and Influences

The Parisian art scene in the mid-eighteenth century was dominated by the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture), the premier institution for artistic training and a gateway to royal commissions and recognition. It was here that Delarue honed his skills, eventually winning the prestigious Prix de Rome for sculpture in 1750 or 1751. This coveted prize granted him a period of study at the French Academy in Rome, a transformative experience for many French artists.

During his time in Rome, from approximately 1754, Delarue was exposed firsthand to the masterpieces of classical antiquity and the Italian Renaissance and Baroque. This immersion was crucial in shaping his understanding of form, composition, and narrative. While in Rome, he is known to have been influenced by prominent sculptors such as Lambert-Sigisbert Adam (1700–1759), who had himself spent considerable time in Rome and was known for his dynamic, Bernini-esque style. Another significant influence was likely Clodion (Claude Michel, 1738–1814), a younger contemporary but one whose terracotta sculptures, full of sensuous charm and mythological fancy, would come to epitomize the Rococo spirit in sculpture. Delarue's Roman sojourn also saw him engage in practical design work, notably creating patterns for a royal porcelain manufactory, indicating an early and sustained interest in the decorative arts.

Upon his return to Paris, Delarue continued to develop his multifaceted career. While his sculptural output included works that sometimes relied on designs by the preeminent Rococo painter François Boucher (1703–1770), Delarue's own drawings and designs reveal a distinct artistic personality. Boucher's influence, however, is undeniable in the broader context of the Rococo, with his popularization of pastoral scenes, mythological idylls, and a light, airy palette setting the tone for much of the era's artistic production.

Thematic Concerns and Stylistic Traits

Louis-Félix Delarue's oeuvre reflects the prevailing tastes of the Rococo period, with a particular fondness for mythological narratives, bacchanalian scenes, religious subjects reinterpreted with a gentle grace, and charming depictions of childhood. His style is characterized by fluid lines, a delicate touch, and a keen sense of decorative arrangement.

Mythological and Bacchanalian Revelries:

A significant portion of Delarue's known work, particularly his drawings and etchings, explores classical mythology. Themes of Bacchus (Dionysus), Silenus, Venus, and Ceres recur, allowing for dynamic compositions filled with playful putti, satyrs, and nymphs. These subjects were immensely popular in the Rococo era, offering opportunities for artists to depict joyous abandon, sensual beauty, and the bounty of nature. His work The March of Silenus, an etching now housed in the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. (from the Leo Steinberg bequest), exemplifies this interest. Silenus, the portly, jovial attendant and tutor of Bacchus, is often depicted in a drunken procession, a theme that allowed for boisterous energy and a celebration of earthly pleasures.

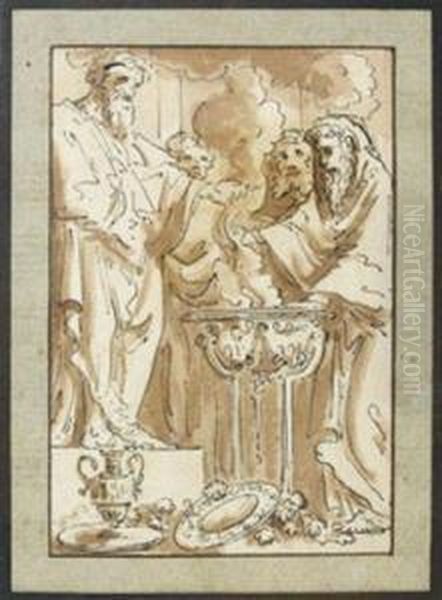

Another notable work is a drawing titled Bacchanale, executed in watercolor and ink (27 x 21.2 cm, late 18th century – though this dating might refer to a later copy or a broader period attribution if Delarue died in 1765). Such scenes typically feature dancing figures, flowing wine, and an atmosphere of unrestrained festivity, all rendered with the characteristic lightness and elegance of the Rococo. Similarly, his Cérémonie en l'honneur de Cérès (Ceremony in Honor of Ceres), a drawing in ink and white pigment (10 x 32.5 cm, c. 1770 – again, dating needs careful consideration against his death date), would have depicted rituals associated with the Roman goddess of agriculture, grain, and fertility, often involving processions and offerings.

Religious Subjects with Rococo Grace:

While the Rococo is often associated with secular themes, religious art continued to be produced, albeit often imbued with a softer, more humanized sensibility than the dramatic intensity of the preceding Baroque era. Delarue is noted for specializing in religious subjects, and one of his significant works in this vein is Samson and the Betrayal of Delilah. This subject, drawn from the Old Testament, tells the dramatic story of Samson's downfall through Delilah's treachery. Delarue's rendition, a watercolor with ink outlines (33 x 25 cm, late 18th century – again, the dating is curious), was recorded in the holdings of the ZISSKA & L auction house in Munich. Another source mentions a work of this title at Rockoxhuis, Antwerp. Regardless of its precise current location, the choice of watercolor and ink suggests a more intimate and perhaps less monumental treatment of the theme than one might find in a large-scale oil painting. The focus would likely be on the emotional interplay and the decorative potential of the figures and drapery.

The World of Childhood and "Kinderoper":

An intriguing aspect of Delarue's specialization was his focus on "Kinderoper" (children's opera) or children's songs. This aligns with the Rococo's fascination with childhood, often depicted as a realm of innocence, playfulness, and charm. Artists like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699–1779) excelled in portraying children with sensitivity, and Boucher frequently included cherubic putti in his mythological scenes. Delarue's engagement with themes suitable for children's opera suggests he may have created designs for stage sets, costumes, or illustrations related to this genre. This interest underscores the Rococo's embrace of lighter, more delightful subject matter, moving away from the grandiosity of earlier periods.

Mastery of Drawing and Etching:

Delarue's drawings are particularly praised for their technical skill and expressive quality. He employed a variety of media, including ink, wash, chalk, and charcoal, often in combination. His line work is described as fluid and confident, capable of capturing movement and conveying emotion. Works like Soldat à la taverne (Soldier at the Tavern), executed in ink and black pencil, would have showcased his ability to depict genre scenes with character and vivacity. His etchings, such as The March of Silenus, demonstrate his proficiency in printmaking, a medium that allowed for wider dissemination of his compositions. The use of dynamic lines and geometric shapes, combined with careful attention to shading and texture, created visually engaging works.

Contributions to the Decorative Arts

Beyond his work as a painter and sculptor, Louis-Félix Delarue made significant contributions to the decorative arts, an area where the Rococo style found its most exuberant expression. His ability to create intricate and elegant designs made him a sought-after talent for a variety of applications.

Designs for Ceramics and Porcelain:

His work for a royal porcelain manufactory in Rome during his studies there was an early indication of his aptitude for decorative design. The eighteenth century was a golden age for European porcelain, with manufactories like Sèvres in France, Meissen in Germany, and Capodimonte in Naples producing exquisite wares. Delarue's designs would have likely included figural scenes, floral motifs, and ornamental patterns suitable for adorning vases, tableware, and decorative figurines. His understanding of classical themes and his Rococo sensibility would have translated well to the delicate surfaces of porcelain. His design Hymn to Venus, possibly intended for ceramics, featuring figures of Titus and Bacchus, highlights his focus on symmetry and pleasing layout, essential qualities for decorative applications.

Ornamental Designs for Boxes, Clocks, and More:

Delarue's talent extended to designing a wide range of decorative objects. He is known to have created designs for the tops and bottoms of small rectangular boxes, items that were fashionable accessories in the eighteenth century. These designs, often executed in deep brown ink, black ink, and grey-black chalk, with black charcoal outlines, would have featured miniature scenes or intricate patterns, showcasing his meticulous attention to detail.

He also designed for horology. An example is a Louis XV ormolu-mounted kingwood and parquetry longcase clock, where the design of the bronzes is attributed to him. Such clocks were not merely time-telling devices but elaborate pieces of furniture and status symbols, adorned with intricate gilt bronze mounts often depicting mythological figures, floral swags, and rocaille (shell-like) motifs. His involvement with such projects underscores his versatility and his ability to work across different media and scales. The design for Automne (Autumn) is another example of his work in this decorative vein.

His approach to decorative design emphasized elegance, harmony, and a playful integration of natural forms with abstract ornament. This aligned perfectly with the Rococo aesthetic, which sought to beautify every aspect of aristocratic life, from grand interiors to personal trinkets.

Delarue in the Context of His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Louis-Félix Delarue's contributions, it is essential to view him within the rich artistic milieu of his time. He worked alongside and was influenced by some of the leading figures of the French Rococo and early Neoclassicism.

As mentioned, François Boucher was a towering figure whose style permeated many aspects of Rococo art. Delarue's occasional reliance on Boucher's designs for sculptural projects speaks to Boucher's pervasive influence. Other prominent painters of the era included Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806), known for his exuberant and sensuous depictions of love and leisure, and Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, whose quiet domestic scenes and still lifes offered a contrast to the more flamboyant Rococo style but were equally esteemed. Charles-Joseph Natoire (1700–1777), who served as director of the French Academy in Rome during part of Delarue's stay, was another key painter whose work, often on a grand scale, decorated many royal and aristocratic residences. Carle Van Loo (1705–1765), a versatile artist who excelled in history painting, portraiture, and mythological scenes, was also a dominant figure in the French art establishment.

In sculpture, besides Lambert-Sigisbert Adam and Clodion, Delarue's contemporaries included Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne (1704–1778), a renowned portrait sculptor; Étienne Maurice Falconet (1716–1791), famous for his graceful marble sculptures and his work for the Sèvres porcelain manufactory (notably the Menacing Cupid); and Jean-Baptiste Pigalle (1714–1785), whose works ranged from intimate genre pieces to monumental tombs. Edmé Bouchardon (1698–1762), though leaning more towards a restrained, classicizing style that anticipated Neoclassicism, was also a highly respected sculptor of the period.

The field of decorative arts and design was equally vibrant. Figures like Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (1695–1750), an architect, painter, and goldsmith, was a key proponent of the extreme Rococo, or "genre pittoresque." His asymmetrical designs and lavish ornamentation had a profound impact. Similarly, Gilles-Marie Oppenordt (1672–1742) was an influential architect and decorator whose work helped define the Régence and early Rococo styles. Delarue's work in decorative design fits into this broader context of artists who blurred the lines between the "fine" and "applied" arts.

Other artists whose activity overlapped with Delarue's include the Venetian painter Jacopo Amigoni (1682–1752), who worked internationally and whose light, decorative style was influential in the Rococo. While some names like Amiel Louis-Felix, Anders Andersen, Sophie Anderson, Alex de Alexe, Antonio Allegri (Della Robbia), Friedrich von Amerling, Fra Angelico, Giovanni Battista Bernini (though earlier, his Baroque influence was still felt), Richard Ansdell, Appiani, Aubert, and Enrico Enriquez de la Serna y Azbe are mentioned in some contexts, their direct contemporaneity or stylistic relevance to Delarue in the Parisian Rococo scene varies greatly. For instance, Bernini and Fra Angelico belong to much earlier periods, though their legacy was, of course, part of the artistic heritage Delarue would have studied. The most pertinent contemporaries are those active in the French Rococo and early Neoclassical movements.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Louis-Félix Delarue's career, though spanning only a few decades, left a mark on eighteenth-century French art, particularly in the realm of drawing and decorative design. His works are characterized by their technical refinement, imaginative compositions, and embodiment of the Rococo spirit. While he may not have achieved the same level of posthumous fame as Boucher or Fragonard, his contributions were recognized in his time, as evidenced by his Prix de Rome and his work for prestigious clients and manufactories.

His drawings and etchings continue to be appreciated for their artistic merit and are found in collections such as the National Gallery of Art. The fact that his works, like the Sacrifice Scene (pen and grey ink, 21 x 27 cm, sold at auction for €1,500), still appear on the art market and command respectable prices indicates a sustained interest among collectors and connoisseurs.

Delarue's art reflects a period of transition, where the exuberance of the Rococo was beginning to encounter the more restrained and ordered aesthetics of Neoclassicism. His engagement with classical themes can be seen as part of this broader cultural current, yet his execution often retained the lightness and charm characteristic of the Rococo.

His specialization in decorative arts is particularly significant. The Rococo era saw an unprecedented integration of art into everyday life, with an emphasis on creating harmonious and aesthetically pleasing environments. Delarue's designs for porcelain, boxes, and clocks contributed to this culture of refinement and elegance. His ability to translate mythological and pastoral themes into decorative motifs suitable for a variety of objects demonstrates his versatility and his keen understanding of the principles of design.

In conclusion, Louis-Félix Delarue was a skilled and versatile artist whose work captures the essence of the French Rococo. As a sculptor, draftsman, etcher, and decorative designer, he moved fluidly between different media, consistently producing works of charm, elegance, and technical proficiency. His depictions of mythological revelries, his sensitive approach to religious themes, his engagement with the world of childhood, and his exquisite decorative designs all contribute to a portrait of an artist who, while perhaps not a revolutionary figure, was a consummate craftsman and a worthy representative of his era's artistic achievements. His legacy lies in these refined creations, which continue to offer a window into the sophisticated and pleasure-loving world of eighteenth-century France.