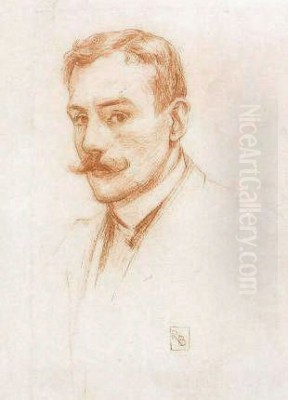

Rupert Charles Wulsten Bunny (1864-1947) stands as one of Australia's most celebrated and successful expatriate artists, a figure whose life and work bridged the artistic worlds of Melbourne and Paris during a period of profound cultural transformation. Born in St Kilda, Melbourne, into a well-to-do family, Bunny's early life provided him with a broad education that initially included studies in architecture and engineering, reflecting perhaps his father's practical inclinations. However, his artistic calling soon became undeniable.

His formal art training began in his native Melbourne at the prestigious National Gallery School, where he studied from 1881 to 1883. This institution was a crucible for Australian art, and Bunny studied alongside contemporaries who would also become significant figures in the nation's art history, including key members of the Heidelberg School like Arthur Streeton and Frederick McCubbin. This early immersion in the burgeoning Australian art scene provided a foundation, though his artistic destiny lay primarily overseas.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

In 1884, at the age of twenty, Bunny accompanied his father, Judge Brice Frederick Bunny, to Europe, a move that would decisively shape his artistic trajectory. His pursuit of advanced art education began in London. He enrolled at P. H. Calderon's School in St John's Wood, studying under Philip Hermogenes Calderon, a painter known for his historical and genre scenes, often with a literary or classical bent. This initial exposure to the London art world, still heavily influenced by Victorian academicism and the legacy of the Pre-Raphaelites, provided a grounding in traditional techniques.

However, the magnetic pull of Paris, the undisputed centre of the art world at the time, proved irresistible. Bunny relocated to the French capital to further hone his skills. He studied under the acclaimed history painter Jean-Paul Laurens, a master known for his large-scale historical and religious compositions executed with dramatic intensity and meticulous detail. Bunny absorbed Laurens's rigorous approach to figure drawing and composition, likely attending his atelier or possibly studying with him at the Académie Colarossi, a popular alternative to the more conservative École des Beaux-Arts. This training under Laurens was crucial in developing Bunny's proficiency in academic historical painting, a genre he would initially embrace.

His time in Paris immersed him in a vibrant and rapidly evolving artistic milieu. He encountered the lingering influence of Academic art, the revolutionary impact of Impressionism, the rise of Symbolism, and the stirrings of early Modernism. This rich environment provided fertile ground for an artist of Bunny's sensibility, allowing him to absorb diverse influences while forging his own distinct path. He also formed connections within the Parisian art community, associating with figures like the painters Leon Glaize and Benjamin Constant, further integrating him into the city's artistic life.

Parisian Success and Recognition

Rupert Bunny spent nearly five decades of his life based primarily in Paris, establishing himself as a significant figure within the city's competitive art scene. His talent was recognized relatively early in his European career. A major breakthrough occurred in 1890 when his painting Tritons, a dynamic mythological scene showcasing his academic training and a burgeoning interest in Symbolist themes, was awarded a mention honorable (honourable mention) at the prestigious Paris Salon. This distinction was highly significant, making Bunny the first Australian artist ever to receive such an accolade at the Salon, instantly raising his profile.

His success continued. At the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) held in Paris in 1900, a major international event showcasing global achievements in arts and industry, Bunny was awarded a bronze medal. The work recognized on this occasion was likely his Burial of St. Catherine of Alexandria, a piece demonstrating his skill in handling complex religious narratives with sensitivity and decorative flair. These awards were not mere tokens; they represented significant validation from the highest echelons of the European art establishment.

Perhaps the most telling indicator of his standing came in 1904. The French state acquired his painting Après le bain (After the Bath) for its national collection, housed at the Musée du Luxembourg, which was then the museum dedicated to living artists. This purchase marked another historic first: Bunny became the first Australian painter to have work bought by the French government. Après le bain exemplifies the elegant, sophisticated style Bunny developed, depicting fashionable women in leisurely moments, characteristic of the Belle Époque era. This acquisition cemented his reputation as an artist of international calibre, admired not just by critics and fellow artists but also by official institutions.

Throughout his long Parisian sojourn, Bunny exhibited regularly at the Salon de la Société des Artistes Français (the "Old Salon") and later at the more progressive Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (the "New Salon"). His work gained popularity, finding favour with audiences who appreciated his blend of technical skill, elegant subject matter, and decorative sensibility. He became one of the most prominent and respected Australian artists working abroad during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Artistic Style and Influences

Rupert Bunny's artistic style is characterized by its sophisticated synthesis of diverse influences, evolving significantly over his long career yet always retaining a distinctive elegance and sensitivity to colour and form. He was never rigidly attached to a single movement but adeptly absorbed elements from various sources, creating a unique visual language. His foundations lay in the academic tradition, evident in his skilled draughtsmanship and compositional structures learned under masters like Jean-Paul Laurens and Philip Calderon.

Early works often show the influence of British art, particularly the aesthetic sensibilities of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and their followers, with their attention to detail, literary themes, and sometimes melancholic beauty. However, living in Paris exposed him directly to the currents transforming European art. The atmospheric light and broken brushwork of French Impressionism clearly impacted his handling of paint and light, particularly in his depictions of outdoor scenes and intimate interiors.

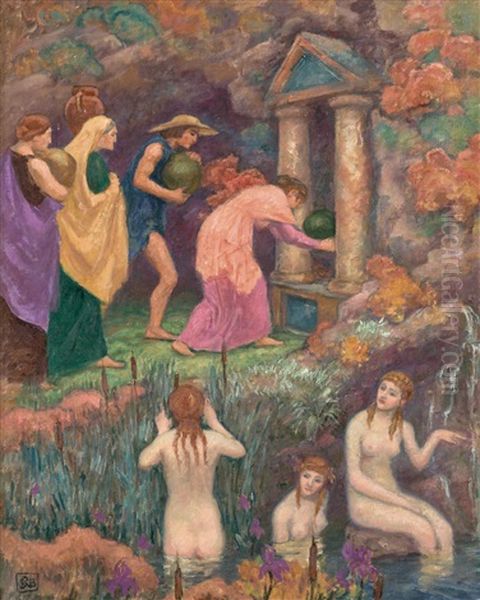

Symbolism also played a crucial role, especially in his mythological and allegorical works from the 1890s and early 1900s. These paintings often feature dreamlike atmospheres, suggestive narratives, and a focus on mood and emotion over strict realism, echoing the concerns of Symbolist painters across Europe. His mythological subjects, often drawn from Greek and Roman lore—an interest perhaps nurtured by his German-born mother—were rendered with a sensuousness and decorative quality that set them apart.

Bunny was an exceptional colourist throughout his career. His palette evolved from the more subdued tones of his early academic work to the brighter, more vibrant hues seen in his Belle Époque paintings. He demonstrated a remarkable ability to harmonize colours, creating rich, decorative surfaces. This sensitivity to colour and rhythm aligns him with French Post-Impressionist artists like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, members of the Nabis group known for their emphasis on pattern and colour. There are also echoes of the bold colour experiments of Paul Gauguin in some of Bunny's more decorative compositions.

In later phases, particularly works created around the 1920s, Bunny embraced elements closer to Modernism. Paintings like Summer time exhibit flattened perspectives, simplified forms, and bold, almost Fauvist blocks of colour, demonstrating his ongoing engagement with contemporary artistic developments. He drew inspiration from Old Masters as well, admiring the compositional dynamism of Peter Paul Rubens and the dignified portraiture of Diego Velázquez, integrating lessons from art history into his distinctly modern vision. His style remained fundamentally representational but was infused with a modern decorative sensibility.

Themes and Subject Matter

The thematic range of Rupert Bunny's work is remarkably broad, reflecting his diverse interests and the changing cultural landscape he inhabited. His oeuvre encompasses grand mythological and biblical narratives, intimate portraits, elegant scenes of contemporary Parisian life, serene landscapes, and later, more personal and introspective compositions.

Mythology and biblical stories were prominent subjects, particularly in his earlier Salon submissions. Works like Tritons (1890), Angels Descending, and The Burial of St. Catherine of Alexandria (c. 1900) allowed him to showcase his academic training in figure composition and narrative painting. These paintings often possess a Symbolist quality, imbuing ancient tales with a sense of mystery, sensuality, or spiritual contemplation. His depiction of Salome aligns with a popular fin-de-siècle fascination with femme fatales and exotic biblical figures. La Chasse (The Hunt) similarly draws on classical or mythological hunting themes, rendered with decorative elegance.

A significant portion of Bunny's output, especially during the height of his Parisian success in the early 1900s, focused on capturing the leisured elegance of the Belle Époque. Paintings like Après le bain (1904), A Summer Morning, and numerous depictions of women reading, playing music, or relaxing in sun-dappled gardens or chic interiors, celebrate the sophisticated social milieu he frequented. These works are characterized by their graceful figures, fashionable attire, harmonious colour schemes, and an atmosphere of tranquil refinement. He excelled at portraying the textures of fabrics, the play of light, and the quiet moments of everyday upper-class life.

Portraiture was another important aspect of his practice. He painted numerous portraits, often of women, including many sensitive depictions of his wife, Jeanne Heloise Morel. These portraits combine psychological insight with his characteristic decorative flair. Landscapes also feature in his work, often serving as idyllic settings for his figure compositions or explored for their own atmospheric qualities, particularly scenes from the south of France where he sometimes stayed.

In his later years, after returning to Australia, his subject matter shifted again, incorporating more landscapes inspired by his homeland and revisiting mythological themes, but often rendered with a bolder, more simplified, and modern aesthetic. These late works sometimes carry a nostalgic or introspective tone, reflecting on memory and personal history. Throughout his career, Bunny demonstrated a consistent ability to adapt his style to suit his chosen theme, whether aiming for narrative grandeur, social elegance, or decorative abstraction.

Personal Life and Connections

Rupert Bunny's personal life, particularly his long marriage, was intertwined with his artistic career. In 1895, while living and working in Paris, he met Jeanne Heloise Morel, a French art student who became his model, muse, and eventually his wife. Jeanne was herself an artist, reportedly influenced by Impressionism and the bohemian artistic circles of Paris. They married in 1902, and their partnership lasted for three decades until Jeanne's death in 1932.

Jeanne featured frequently in Bunny's paintings, often depicted with an air of elegance and quiet introspection. Her presence in his work provides a personal counterpoint to his more public Salon pieces. Their life together in Paris placed them within a cosmopolitan artistic and social environment. Bunny's background—born in Australia to an English father and a German mother who instilled in him an early love for music and mythology—gave him a naturally international outlook.

Beyond painting, Bunny possessed considerable musical talent. He was an accomplished pianist and even composed music, sometimes creating pieces inspired by his own paintings. Reports suggest he occasionally performed his compositions at social gatherings or salons in Paris, highlighting a multi-faceted artistic sensibility that extended beyond the visual arts. This musicality may also inform the strong sense of rhythm and harmony evident in his painted compositions.

His connections within the art world were extensive, both in Paris and internationally. He knew many artists, writers, and musicians. His friendships included fellow expatriate artists as well as French figures like Leon Glaize and Benjamin Constant. Despite spending the majority of his adult life in Europe, he maintained connections with Australia, occasionally sending works back for exhibition and keeping abreast of developments in his homeland. The death of his wife Jeanne in 1932 marked a significant turning point, prompting his decision to leave Paris and return permanently to Australia the following year.

Later Years and Return to Australia

Following the death of his wife Jeanne in 1932, Rupert Bunny made the decision to leave Paris, the city that had been his home and the centre of his artistic life for nearly fifty years. In 1933, he returned to Australia, settling in South Yarra, a suburb of Melbourne, where he would spend the remainder of his life. This return marked a significant shift, bringing him back to the country of his birth after decades immersed in the European art world.

Despite his long absence, Bunny sought to re-engage with the Australian art scene. However, the artistic landscape in Australia had changed considerably since his departure in the 1880s. Modernism had taken root, and new generations of artists were exploring different directions. While respected as a senior figure with a distinguished international reputation, his elegant, European-inflected style perhaps seemed somewhat out of step with the prevailing trends in Australian art during the 1930s and 40s, which often emphasized national identity and landscape.

Nevertheless, Bunny continued to paint actively during his later years. His late works often revisited mythological themes, but treated them with a new boldness and simplification of form, reflecting his ongoing engagement with modernist aesthetics. He also painted landscapes and compositions inspired by memory and personal experience, sometimes depicting scenes related to his mother or his early life. These later paintings often possess a vibrant energy and a directness that contrasts with the refined polish of his Belle Époque works.

His stature was acknowledged in Australia. In 1946, the National Gallery of Victoria mounted a major retrospective exhibition of his work. This exhibition proved highly popular, attracting over 25,000 visitors—a testament to the public's enduring interest in his art and his significant reputation. Despite facing financial difficulties in his later years, he continued to create art until his death in Melbourne in 1947. His return allowed Australia to reclaim one of its most internationally successful artistic sons, ensuring his legacy within his home country.

Legacy and Influence

Rupert Bunny's legacy is that of a highly accomplished and sophisticated artist who achieved significant international recognition while remaining an important figure in Australian art history. As one of the nation's most successful early expatriate painters, he demonstrated that Australian artists could compete and succeed on the world stage, particularly within the demanding environment of Paris. His achievements, including the Paris Salon mention honorable and the acquisition of his work by the French state, were pioneering milestones for Australian art.

His influence can be seen in several areas. His technical mastery, particularly his skill as a draughtsman and colourist, set a high standard. His ability to synthesize diverse artistic influences—from academic tradition and Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics to Impressionism, Symbolism, and elements of Modernism—resulted in a unique and evolving style that reflected the complex transitions of European art from the late 19th to the early 20th century. His elegant depictions of Belle Époque life remain iconic representations of that era's leisured refinement.

While his direct stylistic influence on subsequent generations of Australian artists might be less pronounced than that of the Heidelberg School painters he studied alongside, his work has continued to be admired for its sophistication and decorative qualities. Some later artists did find inspiration in his approach. For instance, the Melbourne abstract painter Roger Kemp reportedly admired the sense of rhythm, balance, and underlying structure in Bunny's compositions, particularly his mythological works, finding echoes of a 'primitivism' or essential force that resonated with Kemp's own spiritual and formal explorations. Bunny's occasional work in other media, such as monotypes, also pointed towards multi-disciplinary artistic practice.

Bunny's work is held in numerous major public collections in Australia, including the National Gallery of Australia, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the National Gallery of Victoria, and the Queensland Art Gallery, as well as internationally in institutions like the Musée d'Orsay in Paris (which inherited works from the Musée du Luxembourg). His reputation has been periodically reassessed and reaffirmed through major retrospective exhibitions, such as the one organized by the National Gallery of Australia in 1991 and the comprehensive survey Rupert Bunny: Artist in Paris held at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2009. These exhibitions have reintroduced his diverse body of work to new audiences, highlighting his versatility and enduring appeal.

He remains a key figure for understanding the connections between Australian art and international developments, particularly the rich cultural exchange that occurred through expatriate artists living and working in Europe. His career exemplifies the cosmopolitanism that characterized aspects of Australian cultural life at the turn of the twentieth century.

Conclusion

Rupert Bunny navigated the complex currents of the art world between Melbourne, London, and Paris with remarkable success and adaptability. From his early academic training to his celebrated status as a chronicler of Belle Époque elegance, and through his later explorations of mythology and modernism, he consistently produced work characterized by technical skill, sophisticated composition, and a masterful use of colour. He absorbed the influences of artists ranging from the Pre-Raphaelites and Jean-Paul Laurens to Pierre Bonnard and the Fauves, yet forged a distinctive artistic identity.

As the first Australian artist to gain significant official recognition in Paris, he paved the way for future generations and demonstrated the potential for Australian artists on the international stage. His paintings, whether depicting languid afternoons in Parisian gardens, dramatic mythological encounters, or intimate personal moments, offer a window into the refined aesthetics and cultural transitions of his time. Rupert Bunny's enduring legacy lies in his substantial body of beautiful and intelligent work, and in his role as a significant bridge between the artistic traditions of Australia and Europe.