Lucas Cranach the Younger stands as a significant figure in the German Renaissance, an artist whose life and work were deeply intertwined with the tumultuous religious and political changes of the 16th century. Born into an artistic dynasty, he inherited not only a name but a thriving workshop and a complex legacy. Navigating the shadow of his famous father, Lucas Cranach the Elder, the Younger forged his own path, contributing significantly to the visual culture of the Protestant Reformation and leaving behind a substantial body of work that continues to engage art historians and enthusiasts alike. His career exemplifies the role of the artist in a period of profound transformation, balancing artistic production, commercial success, and civic responsibility.

Early Life and Training in the Cranach Workshop

Lucas Cranach the Younger entered the world on October 4, 1515, in Wittenberg, Saxony, a town that would soon become the epicenter of the Protestant Reformation. He was the second son of Lucas Cranach the Elder (c. 1472–1553), already a renowned painter, printmaker, and court artist to the Electors of Saxony. The Cranach household was not just a home but the hub of a bustling artistic enterprise. Lucas the Younger, alongside his elder brother Hans (c. 1513–1537), received his artistic education directly within this dynamic environment.

The Cranach workshop was one of the largest and most productive in Northern Europe. Training there involved learning the diverse skills required of a Renaissance artist: drawing, painting techniques (including the rapid execution methods favored by the workshop), printmaking (especially woodcut design), and even the business aspects of art production and sales. Lucas the Younger learned by assisting his father and senior workshop members, gradually mastering the distinctive Cranach style characterized by elegant, elongated figures, detailed costumes, and a blend of Gothic sensibilities with Renaissance innovations. His brother Hans was also a talented painter, and the two likely collaborated on workshop commissions during their formative years.

The early death of Hans Cranach in 1537, while traveling in Bologna, Italy, was a significant turning point. This tragedy positioned Lucas the Younger as the sole heir apparent to the Cranach workshop and legacy. He had already been working closely with his father for several years, absorbing the technical skills and stylistic vocabulary that defined the Cranach brand. His apprenticeship was thorough, preparing him not just to paint but to eventually manage the complex operations of the family business.

Inheriting the Mantle: Taking Over the Workshop

From the mid-1530s onwards, Lucas Cranach the Younger's hand becomes increasingly identifiable in works emerging from the Cranach studio. He worked collaboratively with his father, and the stylistic similarities between them, particularly during this transitional period, can make definitive attribution challenging. Lucas the Elder gradually began delegating more responsibility to his son, especially as the Elder became more involved in Wittenberg's civic life, including serving as Bürgermeister (Mayor).

The official transfer of control occurred around 1550, although Lucas the Elder remained active until his death in Weimar in 1553. Upon his father's death, Lucas Cranach the Younger fully inherited the workshop, its stock of drawings and templates, its skilled assistants, and its prestigious reputation. He maintained the workshop's high level of productivity, continuing to fulfill commissions for portraits, altarpieces, and mythological scenes that were in high demand among princely courts, wealthy burghers, and Lutheran congregations.

He proved to be an adept manager, sustaining the workshop's commercial success for several decades. The Cranach workshop under his direction continued to be a major force in the German art market, adapting its output to changing tastes while largely preserving the established Cranach "look." This continuity was crucial for maintaining the brand recognition that his father had so carefully cultivated. He signed his works with the same insignia his father had used since 1508: the winged serpent, sometimes with slight variations that occasionally help distinguish their periods of activity.

Artistic Style: Continuity and Innovation

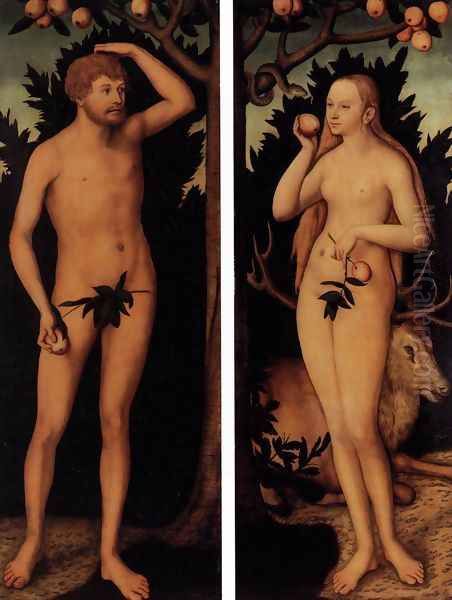

The art of Lucas Cranach the Younger is fundamentally rooted in the style developed by his father. He mastered the elegant linearity, the detailed rendering of textures (especially fabrics and jewels), and the distinctive physiognomies associated with the Cranach name. His portraits often feature the same smooth, enamel-like finish and dark, neutral backgrounds favored by his father, focusing attention entirely on the sitter. Themes popularised by the Elder, such as Venus, Lucretia, Judith, and Adam and Eve, continued to be produced under the Younger's direction.

However, subtle differences and developments mark Lucas the Younger's independent artistic personality. Some scholars note a tendency towards brighter, sometimes more decorative color palettes compared to the often more somber tones used by his father, particularly in the Elder's later works. His figures can sometimes appear slightly softer or more rounded than the sometimes starker, more angular forms of his father. He also showed a greater inclination towards incorporating more elaborate architectural elements and detailed landscape backgrounds in some compositions, moving slightly away from the plain backdrops often used by his father for portraits.

While adept at replicating the established Cranach formulas, particularly in mythological and allegorical scenes featuring sensuous female nudes, some critics, both contemporary and modern, have found his work occasionally lacking the psychological depth, emotional intensity, or raw innovative power seen in the best works of Lucas Cranach the Elder or their great German contemporary, Albrecht Dürer. His figures, while graceful, can sometimes feel more formulaic or less imbued with the nervous energy that characterizes some of his father's most compelling pieces, such as the early portraits or expressive religious scenes. Nevertheless, his technical skill remained high throughout his career.

Portraiture: Capturing the Faces of an Era

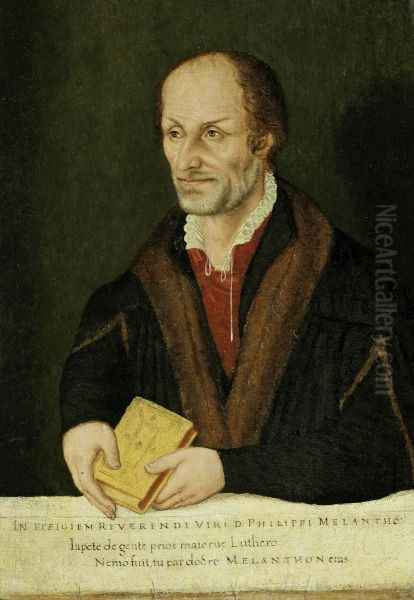

Portraiture was a cornerstone of the Cranach workshop's output, and Lucas the Younger excelled in this genre. He continued the tradition of portraying the key figures of the Protestant Reformation, including Martin Luther, Philipp Melanchthon, and their families. These portraits were crucial for disseminating the image of the reformers and solidifying their status. The workshop produced numerous versions of these portraits, often based on standard templates, catering to a wide demand. Lucas the Younger's portraits of Luther, particularly those made later in the reformer's life and posthumously, are defining images of the Reformation leader.

Beyond the circle of reformers, Cranach the Younger painted numerous portraits of Saxon electors, dukes, their consorts, and other members of the German nobility. These works served as important tools of dynastic representation and political diplomacy. His portraits, like those of his father, are characterized by meticulous attention to costume and insignia, clearly denoting the sitter's rank and status. Examples include his depictions of Elector Johann Friedrich I of Saxony and his family.

He also captured the likenesses of wealthy burghers and scholars. His female portraits are particularly noteworthy, often depicting women in elaborate, fashionable attire with intricate hairstyles and jewelry. Works like the Portrait of Barbara Radziwill exemplify his skill in rendering rich fabrics and capturing a sense of aristocratic poise, though sometimes with a certain emotional reserve typical of the Cranach style. His Self-portrait from around 1550-1560 shows him as a confident, successful master, gazing directly at the viewer. His ability to capture the specific features of older sitters, revealing the marks of age with sensitivity, is also a recognized strength.

Religious Art in the Age of Reformation

Lucas Cranach the Younger lived and worked during the height of the Protestant Reformation, and his art reflects this context profoundly. Following his father's example, he became a key visual propagandist for the Lutheran cause. The Cranach workshop produced numerous altarpieces and devotional paintings tailored to Lutheran theology, emphasizing salvation through faith alone (sola fide) and the centrality of scripture.

One of the most important theological themes visualized by both Cranachs is The Law and the Gospel. Lucas the Younger created several versions of this didactic composition, which contrasts the damnation resulting from adherence to Old Testament Law with the salvation offered through grace by Christ's sacrifice, as preached in the Gospels. These complex allegories, often packed with biblical figures and symbols, served as visual sermons, instructing the faithful in core Lutheran doctrines. They stand in contrast to the Catholic emphasis on saints, relics, and papal authority.

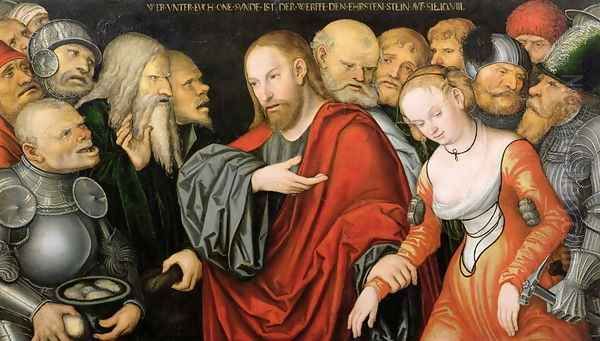

He also painted traditional biblical scenes but often imbued them with a Protestant sensibility. His depiction of Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (versions exist by both father and son) could be interpreted through a Lutheran lens, emphasizing Christ's mercy and forgiveness over condemnation by the law. His rendition of The Last Supper in the main church of Wittenberg notably includes portraits of key reformers like Luther (disguised as an apostle) partaking in the sacrament, visually linking the Reformation movement directly to Christ's foundational act. These works demonstrate how art was strategically employed to legitimize and propagate the new faith. Unlike Albrecht Altdorfer or Matthias Grünewald, whose religious art often conveyed intense mysticism or emotional drama, the Cranachs' religious works often prioritized clarity, didacticism, and theological correctness according to Lutheran principles.

Mythological and Allegorical Themes

Alongside religious commissions, the Cranach workshop under Lucas the Younger continued to produce mythological and allegorical paintings, often featuring elegant female nudes. These subjects, drawn from classical antiquity or humanist allegory, were popular among the courtly and educated clientele. Themes like Venus (often paired with Cupid), the Judgment of Paris, Lucretia, and various depictions of mismatched couples (illustrating the power of women or the folly of old men) remained staples of the workshop's repertoire.

These works often carry moralizing undertones, reflecting humanist interests in classical stories as vehicles for ethical lessons. However, they also clearly catered to a taste for the sensuous and decorative. The distinctive Cranach female nude – slender, pale-skinned, often adorned with elaborate hats, jewelry, and diaphanous veils, and set against dark backgrounds or stylized landscapes – became a hallmark of the workshop. Lucas the Younger continued this tradition, producing numerous variations on these popular themes.

While stylistically similar to his father's versions, some art historians find the Younger's mythological figures occasionally more generalized or less psychologically intriguing than the Elder's sometimes enigmatic or subtly subversive depictions. Nonetheless, these paintings were highly sought after and contributed significantly to the workshop's financial success. They represent a fascinating aspect of the Cranach legacy, blending Renaissance humanism with a distinct Northern European aesthetic, quite different from the idealized nudes of Italian contemporaries like Titian or Raphael.

The Cranach Workshop: A Model of Production

The success of Lucas Cranach the Younger was inseparable from the efficient operation of the workshop he inherited. This was not the solitary studio of a lone genius but a well-oiled machine designed for high-volume production. The workshop employed numerous apprentices, journeymen painters, and specialists (perhaps in backgrounds, drapery, or specific details). Standardization was key: preparatory drawings and cartoons were reused, compositions were adapted and varied, and different quality levels could be produced to suit different budgets.

This system allowed the workshop to respond quickly to market demands and produce large series of paintings, such as multiple portraits of reformers or popular mythological subjects. While Lucas the Younger would have overseen production, designed key compositions, and likely painted the most important passages or commissions himself, much of the output inevitably involved significant contributions from workshop assistants. This collaborative nature is a primary reason for the attribution difficulties that plague Cranach scholarship.

The workshop's impact extended beyond painting. It was closely linked to printmaking, producing woodcuts for book illustrations (including Luther's German Bible translation) and single-leaf prints. This print production was vital for the rapid dissemination of both Reformation ideas and the Cranach style itself. The business acumen established by Lucas the Elder, which included ventures like a pharmacy and a bookshop, was continued by his son, making the Cranach enterprise a powerful economic entity in Wittenberg. This model of a large, commercially savvy workshop contrasts with the practices of artists like Hans Holbein the Younger, who, while also highly successful, operated on a different scale and model, particularly during his time in England.

Civic Life and Political Connections

Like his father, Lucas Cranach the Younger was not only an artist but also a prominent citizen of Wittenberg. He integrated himself into the civic structure of the town, demonstrating considerable social standing and administrative skill. He served multiple terms on the town council and held the prestigious office of Bürgermeister (Mayor) in 1565/66. This level of civic involvement was unusual for artists of the period, although not unheard of (Peter Paul Rubens later achieved similar status in Antwerp).

His civic roles underscore the family's established position within the Wittenberg elite. These responsibilities would have demanded significant time and energy, suggesting his ability to effectively delegate tasks within the workshop. His political connections, inherited from his father and maintained through his own activities, were crucial for securing patronage from the Saxon court and other influential clients. The Cranachs' close relationship with the Electors of Saxony provided a stable foundation for their artistic enterprise.

His political life and artistic production were often intertwined. His portraits of rulers served political functions, and his religious art actively supported the Lutheran faith, which was politically dominant in Saxony. He navigated the complex political landscape of the Schmalkaldic War and its aftermath, maintaining his position and the workshop's productivity despite the turbulent times. His life demonstrates the multifaceted roles a successful master could play in Renaissance society – artist, entrepreneur, and civic leader.

Relationship with Contemporaries

Lucas Cranach the Younger operated within a rich artistic landscape in Germany and Northern Europe, though the towering figures of the earlier generation, like Albrecht Dürer (d. 1528) and Matthias Grünewald (d. 1528), had passed away before his independent career fully blossomed. His most direct point of comparison remains his father. However, his work can be considered alongside other German artists active in the mid-16th century.

Hans Holbein the Younger (d. 1543), while dying relatively early in Lucas the Younger's career, set a standard for meticulous realism and psychological insight in portraiture that contrasts with the more stylized and decorative approach of the Cranach workshop. Artists of the Danube School, such as Albrecht Altdorfer (d. 1538) and Wolf Huber (d. 1553), excelled in expressive landscape painting, an area less central to the Cranach output. Hans Baldung Grien (d. 1545), another Dürer protégé, explored darker, more idiosyncratic themes in his paintings and prints.

Compared to these contemporaries, the Cranach workshop under Lucas the Younger perhaps prioritized consistency, recognizability, and efficient production over radical innovation. While technically proficient, his work generally adheres to the established family style rather than breaking new ground in the manner of Dürer or Grünewald. In the broader European context, his work differs significantly from the High Renaissance masters of Italy like Raphael (d. 1520) or Leonardo da Vinci (d. 1519), or later Mannerists like Bronzino (d. 1572), whose approaches to form, composition, and idealization were distinct. His Northern contemporaries included figures like Pieter Bruegel the Elder (d. 1569) in the Netherlands, whose focus on peasant life and landscape offered a different artistic vision. The Cranach workshop's strength lay in its successful adaptation and perpetuation of a specific, highly marketable style deeply connected to its Wittenberg context.

Attribution Challenges and Artistic Identity

One of the most persistent issues surrounding Lucas Cranach the Younger is the difficulty of distinguishing his work, especially from the 1530s and 1540s, from that of his father and the wider workshop. Both artists used the same winged serpent signature. While subtle stylistic differences in handling paint, color preference, figure type, and compositional structure have been proposed by scholars like Max J. Friedländer and Jakob Rosenberg, consensus is not always reached. Many works are simply cataloged as "Cranach Workshop."

This ambiguity complicates assessments of Lucas the Younger's individual artistic development and contribution. Was he primarily a faithful follower and manager, or did he possess a more distinct artistic voice that is sometimes obscured by the collaborative nature of the workshop? Some scholars argue for his independent merit, pointing to the quality and consistency of works produced long after his father's death, and highlighting his skill in portraiture and large-scale compositions. Others maintain that the Elder was the primary creative force, and the Younger, while competent, largely replicated established patterns.

These debates highlight the complexities of studying large, family-run workshops where branding and continuity were paramount. The "Cranach" name signified a certain type of product, and Lucas the Younger successfully maintained that brand identity. While this may complicate the modern art historical desire to isolate the individual "genius," it reflects the realities of art production and the market in the 16th century. His identity is perhaps best understood not just as an individual painter, but as the capable heir and director of a major artistic enterprise.

Legacy and Influence

Lucas Cranach the Younger died in Wittenberg on January 25, 1586, leaving behind a prosperous workshop and a significant artistic legacy. He had successfully steered the family enterprise through decades of religious and political change, ensuring the Cranach name remained synonymous with German Renaissance art, particularly in the context of the Reformation. His sons and grandsons continued the artistic tradition, though the workshop's prominence gradually declined in the following century.

His most enduring legacy lies in the vast number of works produced under his direction, which populate museums and collections worldwide. His portraits provide invaluable visual records of the key figures of the Reformation and the German nobility of the era. His religious paintings offer insight into Lutheran theology and the role of art in religious propaganda. His mythological scenes continue to fascinate with their unique blend of Northern Gothic sensibility and Renaissance themes.

While often evaluated in comparison to his more famous father, Lucas Cranach the Younger was a significant artist and cultural figure in his own right. He maintained a major workshop, fulfilled important commissions, participated actively in civic life, and played a crucial role in shaping the visual culture of Lutheran Germany. His career demonstrates the complex interplay of artistic skill, business acumen, family tradition, and historical circumstance that defined the life of a successful master in the German Renaissance. His work, and the enduring questions surrounding the Cranach workshop, continue to stimulate study and appreciation.