Luca Longhi (1507-1580) stands as a significant, if somewhat localized, figure in the vibrant tapestry of 16th-century Italian art. Active primarily in his native Ravenna, Longhi developed a distinct artistic voice that, while rooted in the High Renaissance ideals, also embraced the elegant and sophisticated tendencies of Mannerism. His career, spent almost entirely within the confines of Ravenna, offers a fascinating case study of a provincial master who, despite geographical limitations, produced an oeuvre of considerable quality, particularly in religious altarpieces and portraiture. This exploration will delve into his life, artistic development, key works, influences, and his enduring, albeit regionally focused, legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in Ravenna

Born in Ravenna in 1507, Luca Longhi was destined to become one of the city's most prominent artistic figures of his era. His family, believed to have originated from Bologna, had established themselves in Ravenna by the early 15th century. This connection to Bologna, a significant artistic center in Emilia-Romagna, may have provided early, albeit indirect, exposure to broader artistic currents. Unlike many of his contemporaries who sought fame and fortune in major artistic hubs like Florence, Rome, or Venice, Longhi remained deeply connected to Ravenna, rarely, if ever, venturing far from his birthplace. This lifelong commitment to his native city shaped both the opportunities available to him and the character of his artistic output.

Ravenna itself, while not a primary center of Renaissance innovation on par with Florence or Rome, possessed a rich artistic heritage, most notably its world-renowned Byzantine mosaics. By the 16th century, it was part of the Papal States, and its artistic life, while perhaps more conservative, still provided avenues for patronage through churches, confraternities, and local noble families. It was within this environment that Longhi's talent was nurtured. Information about his specific training is scarce, a common issue for many provincial artists of the period. However, his mature style suggests an awareness of developments in nearby artistic centers, likely absorbed through a combination of travelling artists, a few key local masters, and, crucially, the burgeoning market for reproductive prints.

The Artistic Milieu: High Renaissance to Mannerism

To understand Longhi's art, one must consider the broader artistic climate of Italy during his lifetime. The early 16th century witnessed the High Renaissance, dominated by titans such as Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), whose scientific curiosity and sfumato technique revolutionized painting; Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), whose powerful figural style in painting and sculpture defined the sublime; and Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio, 1483-1520), whose harmonious compositions and graceful figures became an enduring ideal. These artists established a benchmark for classical perfection.

However, by the 1520s, as Longhi was embarking on his career, a new style known as Mannerism began to emerge. Mannerism, often seen as a reaction to or an elaboration upon High Renaissance ideals, favored elegance, artifice, and emotional intensity. Artists like Parmigianino (Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, 1503-1540), with his elongated figures and sophisticated compositions, and Rosso Fiorentino (1494-1540) or Pontormo (Jacopo Carucci, 1494-1557) in Florence, explored more subjective and stylized forms of expression. In Venice, masters like Titian (Tiziano Vecellio, c. 1488-1576) and Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti, 1518-1594) were developing a distinct school characterized by rich color and dramatic lighting, while Paolo Veronese (1528-1588) was celebrated for his opulent and grand-scale narrative scenes. Longhi's work would navigate these currents, absorbing influences selectively to forge his own path.

Stylistic Characteristics: Grace, Color, and Composition

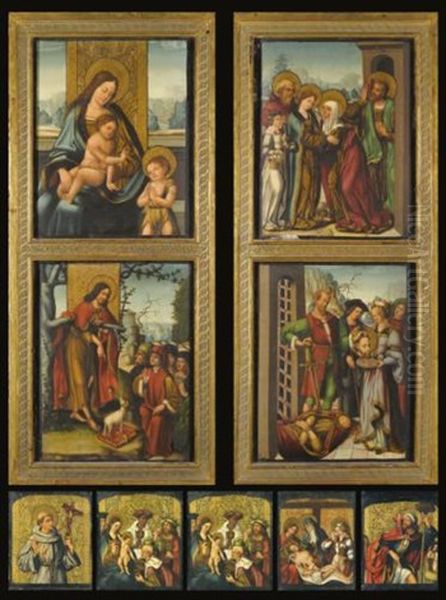

Luca Longhi's artistic style is often characterized by a "graceful serenity and flowing color," as noted in the provided information. This points to an artist who valued clarity, elegance, and a pleasing aesthetic. While he is termed a "Mannerist" painter, his Mannerism is often tempered, less extreme than that of some of his Florentine or Roman contemporaries. He absorbed the elongated proportions and sophisticated poses typical of the style but often retained a sense of balance and calm reminiscent of earlier Renaissance masters.

His handling of color was particularly noteworthy. He employed a palette that could be both rich and subtle, using color to define form, create mood, and unify his compositions. The "flowing color" suggests smooth transitions and harmonious combinations, avoiding the jarring juxtapositions sometimes found in more radical Mannerist works. His compositions, while sometimes complex, generally maintained a sense of order and legibility, crucial for the narrative clarity required in religious altarpieces. He demonstrated a high degree of refinement in his execution, with elegant lines and a careful attention to detail, particularly in fabrics and facial features. This meticulousness contributed to the overall polish and appeal of his paintings.

The influence of Emilian painting, particularly the legacy of Raphael as interpreted by artists in Bologna and Ferrara, is evident. Figures like Francesco Francia (c. 1447-1517), though of an earlier generation, had established a strong tradition of devotional painting in Bologna characterized by gentle piety and refined technique. Later Emilian artists like Innocenzo da Imola (c. 1490-c. 1550) and, more directly contemporary, Correggio (Antonio Allegri da Correggio, c. 1489-1534) from Parma, with his soft sfumato and sensuous grace, also left an indelible mark on the region's art. Longhi seems to have absorbed these influences, likely through prints and perhaps some direct observation, adapting them to his own temperament.

Major Works and Thematic Concerns

Luca Longhi's oeuvre primarily consisted of religious paintings, especially altarpieces for the churches of Ravenna and its environs, and portraiture. These two genres allowed him to showcase different facets of his skill: the narrative and devotional power in his religious scenes, and the psychological insight in his portraits.

One of his most celebrated works is the St. Paul Visiting St. Agnes (sometimes referred to as The Visit of St. Paul to St. Agnes in Prison). Originally an altarpiece for the Church of San Giovanni Evangelista, it is now housed in the Pinacoteca Comunale di Ravenna. This painting likely exemplifies his mature style, showcasing his ability to handle multi-figure compositions, convey emotional states, and utilize color effectively. The interaction between the figures, the rendering of their expressions, and the overall devotional atmosphere would have been key elements.

Another significant work mentioned is The Adoration of the Shepherds (Adorazione dei pastori). This popular theme provided ample opportunity for artists to depict a range of human emotions, from humble adoration to divine grace, and to showcase their skill in rendering figures, animals, and often, atmospheric landscapes or architectural settings. Longhi's version would likely reflect his characteristic elegance and harmonious coloring.

The Cristo Morto Sorriso (The Dead Christ Smiling) is an intriguing title, suggesting a departure from the more typical depictions of the suffering Christ. A smiling dead Christ could imply a serene acceptance of fate or a premonition of the Resurrection, offering a nuanced theological interpretation. This work would highlight Longhi's capacity for subtle emotional expression.

His depiction of Saint Justina of Padua further underscores his engagement with popular saints and devotional imagery. Such paintings were crucial for private devotion and for reinforcing the identities of specific churches or chapels dedicated to these saints.

The Crucifixion with Saints, noted as a late important work for the church of San Domenico in Ravenna, would have been a major commission. Crucifixion scenes were a staple of religious art, demanding a powerful depiction of Christ's suffering, the grief of the Virgin Mary and St. John, and often including other significant saints relevant to the patrons or the church's dedication. Longhi's approach would likely combine dramatic intensity with his inherent sense of order and refined execution.

His portraits, though less discussed in the provided summary, were also an important part of his output. In an era when portraiture was gaining increasing prominence, Longhi's ability to capture a likeness while imbuing the sitter with a sense of dignity would have been highly valued by local patrons. These works would demonstrate his skill in rendering individual features, textures of clothing, and conveying something of the sitter's personality or status.

Influences and Artistic Dialogue (Through Prints)

The provided information rightly notes that Longhi's absorption of influences from masters like Correggio, Raphael, and Parmigianino was often "through prints." This was a common phenomenon in the 16th century. The development of engraving and woodcut techniques allowed for the widespread dissemination of artistic compositions. Artists like Marcantonio Raimondi (c. 1480-c. 1534) famously collaborated with Raphael to create prints after his designs, making Raphael's inventions accessible far beyond Rome. Similarly, prints after Correggio and Parmigianino circulated, allowing artists in provincial centers like Ravenna to study and adapt the latest stylistic innovations.

This reliance on prints meant that Longhi was engaging with these masters' compositional ideas and figural styles, even if he might not have experienced the full impact of their original colors or scale. This indirect transmission could sometimes lead to interesting interpretations and adaptations, as artists filtered these influences through their own local traditions and personal sensibilities.

The mention of "French Classicism" as an influence is somewhat unusual for Longhi's period and location, as French Classicism as a distinct movement is more associated with the 17th century (e.g., Nicolas Poussin, though he worked mostly in Rome). It's possible this refers to a general classicizing tendency, an adherence to clarity and order, which was indeed part of Longhi's style and a counter-current within Mannerism itself, particularly in Emilia-Romagna. The influence of the Carracci family (Annibale, Agostino, and Ludovico Carracci), who spearheaded a reform of painting in Bologna towards the end of Longhi's life and in the decades following, emphasized a return to naturalism and the study of High Renaissance masters. While Longhi would not have been directly influenced by their mature academy, his own clarity might be seen as part of a broader regional preference that later found full expression in the Carracci.

The influence of the Venetian school, particularly the "softness and delicacy of Giorgione" (Giorgione da Castelfranco, c. 1477/8–1510), is more plausible. Venice was a major artistic power, and its emphasis on colorito (color and painterly application) as opposed to Florentine disegno (drawing and design) had a wide impact. Ravenna's geographical position made it somewhat receptive to Venetian influences, and a certain softness or sfumato in Longhi's work could echo Giorgionesque qualities, perhaps transmitted via other North Italian artists or prints.

The Ravenna Context: A Double-Edged Sword

Longhi's decision to remain in Ravenna throughout his career had profound implications. On one hand, it allowed him to become the preeminent painter in his local area, securing consistent commissions from churches and private patrons. He faced less direct competition than he would have in a major artistic center, enabling him to establish a flourishing workshop.

On the other hand, as some scholars have suggested, this provincial setting may have limited his ultimate artistic development and recognition. Had he moved to Rome, Florence, or Venice, he would have been exposed to a more dynamic artistic environment, more diverse patronage, and the direct influence of leading masters. This could have pushed his art in new directions and potentially earned him a wider, more international reputation. The art historian Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, tended to focus on artists from Tuscany and Rome, often giving less attention to masters from other regions, which could also contribute to the relative obscurity of artists like Longhi in broader art historical narratives.

Despite this, Longhi's dedication to Ravenna ensured that the city possessed a body of high-quality artworks reflecting contemporary stylistic trends. His works are now primarily found in Ravenna's churches and museums, such as the Pinacoteca Comunale (which houses works from suppressed religious institutions) and the Biblioteca Classense. These collections are vital for understanding the artistic life of Ravenna in the 16th century.

The Longhi Workshop: A Family Affair

Luca Longhi was not an isolated figure but the head of an active workshop. This was standard practice for successful artists of the period. His workshop would have assisted in preparing canvases, grinding pigments, and executing less critical parts of large commissions. Significantly, his artistic talents were passed down to his children.

His son, Francesco Longhi (1544-1618 or 1620), also became a painter, continuing his father's artistic tradition in Ravenna. Francesco's style, while rooted in his father's teachings, would have also responded to the newer artistic currents of the late 16th and early 17th centuries, including the influence of the Carracci reform emanating from Bologna.

Even more notable, perhaps, was his daughter, Barbara Longhi (1552-1638). Barbara became a respected painter in her own right, a significant achievement for a woman in the 16th century. She specialized in devotional paintings, particularly images of the Madonna and Child, which were praised for their tenderness and refined execution. She often collaborated with her father and brother, and her independent works demonstrate a delicate sensibility and accomplished technique. The success of Barbara Longhi highlights the supportive environment within the Longhi family workshop, which allowed a female artist to flourish professionally. The presence of both Francesco and Barbara ensured the continuation of the Longhi artistic legacy in Ravenna for several decades.

Critical Reception and Historical Standing

Art historical assessment of Luca Longhi acknowledges him as a competent and often elegant painter, the leading artist in Ravenna for much of the 16th century. His works are seen as characteristic of a provincial Mannerism, displaying technical skill, a pleasing sense of color, and an ability to create graceful and devotional images.

However, critiques sometimes point to a certain conservatism or a lack of the innovative power seen in the great masters of the period. His reliance on established compositional formulas and his somewhat restrained emotional range are occasionally noted. Yet, this perceived conservatism might also be seen as a strength, aligning with the devotional needs of his patrons who may have preferred clarity and traditional piety over radical artistic experimentation.

His historical importance lies primarily in his contribution to the artistic heritage of Ravenna and Emilia-Romagna. He represents a significant local flowering of talent, demonstrating how broader Italian artistic trends were absorbed and adapted in regional centers. His works provide valuable insight into the religious and cultural life of 16th-century Ravenna. While he may not have achieved the fame of a Titian or a Michelangelo, his dedication to his craft and his city resulted in an oeuvre that continues to be appreciated for its quiet beauty and refined skill. He stands as a testament to the rich, diverse, and geographically widespread nature of artistic production during the Italian Renaissance and Mannerist periods, where even outside the major metropolises, artists of considerable talent thrived.

Other painters active in Italy during or overlapping Longhi's lifespan, further illustrate the rich artistic environment. For instance, Andrea del Sarto (1486-1530) was a leading painter in Florence during the High Renaissance, known for his harmonious compositions and rich color. In Northern Italy, artists like Lorenzo Lotto (c. 1480-1556/57), with his psychologically insightful portraits and idiosyncratic religious scenes, and Moretto da Brescia (c. 1498-1554), known for his sober realism, carved out distinctive careers. Further south, the dramatic intensity of Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1571-1610) would revolutionize painting at the very end of Longhi's life and in the years following, heralding the Baroque era. These artists, among many others, contributed to the extraordinary artistic vitality of the period.

Conclusion: Ravenna's Refined Master

Luca Longhi's career is a study in dedicated regional artistry. He successfully navigated the stylistic shifts from the High Renaissance to Mannerism, creating a body of work characterized by elegance, harmonious color, and devotional sincerity. While his decision to remain in Ravenna may have circumscribed his national fame, it allowed him to dominate the local artistic scene, producing numerous altarpieces and portraits that enriched the churches and collections of his native city. His legacy was further secured by his children, Francesco and Barbara, who continued the family's artistic tradition. Luca Longhi remains a key figure for understanding the art of Ravenna in the 16th century, a painter whose "graceful serenity and flowing color" still resonate, offering a window into the spiritual and aesthetic values of his time and place. His contribution, though perhaps quieter than that of the era's superstars, is an essential part of the complex and fascinating story of Italian art.