Francesco Granacci (1469–1543) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant artistic milieu of Renaissance Florence. A contemporary and lifelong friend of the colossal Michelangelo, Granacci carved out his own niche, producing a body of work characterized by its graceful figures, harmonious compositions, and rich, often luminous, color. Though perhaps not possessing the revolutionary genius of Leonardo da Vinci or the dramatic power of Michelangelo, Granacci's art reflects a deep understanding of the prevailing artistic currents of his time, skillfully blending influences from his teachers and peers into a distinctive personal style. His career spanned a crucial period of artistic transition, from the late Quattrocento to the High Renaissance and the stirrings of Mannerism, and his paintings offer valuable insights into the artistic dialogues of this dynamic era.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Francesco d'Andrea Granacci was born in Villamagna, a village in the Volterra region, though his artistic life would be inextricably linked with Florence, the epicenter of the Italian Renaissance. His precise birth year is generally accepted as 1469. Like many aspiring artists of his generation, Granacci sought training in one of Florence's leading workshops. He became a pupil of Domenico Ghirlandaio, a master renowned for his fresco cycles and his ability to capture the likenesses of Florentine society.

Ghirlandaio's workshop was a bustling hub of activity and a formative training ground for a remarkable generation of artists. It was here that Granacci not only honed his fundamental skills in drawing, composition, and color but also formed a pivotal friendship with Michelangelo Buonarroti, who was also an apprentice under Ghirlandaio. This bond would endure throughout their lives, providing mutual support and artistic exchange. Other notable artists who passed through Ghirlandaio's studio around this time included Giuliano Bugiardini, further enriching the environment of learning and friendly rivalry.

Beyond the structured environment of Ghirlandaio's workshop, Granacci, along with Michelangelo, also benefited from the patronage and intellectual circle of Lorenzo de' Medici, "il Magnifico." Lorenzo established an informal academy in his sculpture garden near the Convent of San Marco, placing the aged sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni, a former pupil of Donatello, in charge. Here, young artists were exposed to Lorenzo's collection of classical antiquities, fostering a deeper appreciation for Greco-Roman art and humanist ideals. This experience undoubtedly broadened Granacci's artistic horizons, supplementing Ghirlandaio's more traditional, narrative-focused training.

The Enduring Friendship with Michelangelo

The friendship between Francesco Granacci and Michelangelo is one of the most well-documented and touching relationships in Renaissance art history, largely thanks to the accounts of Giorgio Vasari in his "Lives of the Artists." Vasari portrays Granacci as a loyal and supportive friend, playing a crucial role in Michelangelo's early career. It was reportedly Granacci who encouraged the young Michelangelo, then more inclined towards literary pursuits, to dedicate himself to the visual arts and facilitated his entry into Ghirlandaio's workshop.

Throughout their lives, they maintained a close connection. When Michelangelo was summoned to Rome in 1508 by Pope Julius II to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Granacci was among the group of Florentine painters Michelangelo initially called upon for assistance. While Michelangelo famously dismissed most of these collaborators shortly thereafter, preferring to work with a much smaller team or even alone on the vast project, the initial invitation speaks to the trust and esteem he held for Granacci's abilities.

This friendship was not one-sided. Granacci, though perhaps less ambitious or revolutionary in his artistic temperament, provided a steadfast presence in Michelangelo's often tumultuous life. Their correspondence and Vasari's anecdotes suggest a genuine affection and mutual respect that transcended artistic differences. This enduring bond highlights a more personal, human side to the often-intense world of Renaissance artistic production.

Artistic Development and Influences

Granacci's early works, emerging in the 1490s, naturally bear the imprint of his master, Domenico Ghirlandaio, evident in their clear narrative structure and attention to detail. However, he soon began to absorb other influences. The art of Filippino Lippi, with its sinuous lines, expressive figures, and sometimes melancholic beauty, left a discernible mark on Granacci's paintings from this period. Works like his early Madonna and Child panels (an example from circa 1495 is in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin) show a tenderness and a developing command of form.

As the 15th century gave way to the 16th, Florence witnessed the full flowering of the High Renaissance, spearheaded by Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and the young Raphael (who spent formative years in Florence from 1504 to 1508). Granacci was receptive to these powerful new currents. The influence of Fra Bartolomeo (Baccio della Porta), a fellow pupil of Ghirlandaio who became a Dominican friar and a leading exponent of the High Renaissance style in Florence, is particularly notable in Granacci's work from around 1510 onwards. Fra Bartolomeo's emphasis on monumental figures, balanced compositions, and a softer, more atmospheric use of light and shadow (sfumato, partly derived from Leonardo) resonated with Granacci.

Granacci's style evolved to incorporate a greater sense of volume, a more idealized beauty in his figures, and a richer, more harmonious palette. He skillfully navigated the transition from the linear precision of the Quattrocento to the more painterly and volumetric concerns of the Cinquecento. While Michelangelo's dynamic energy and anatomical power were a constant presence, Granacci's temperament led him to a gentler, more lyrical interpretation of the human form. He also absorbed lessons from Raphael's serene classicism and Andrea del Sarto's mastery of color and graceful composition. Later in his career, elements associated with early Mannerism, such as elongated figures and more complex spatial arrangements, as seen in the work of Pontormo, also appear in his paintings.

Major Commissions and Key Works

Francesco Granacci's oeuvre consists primarily of altarpieces, devotional panels, and narrative scenes, often with religious themes. One of his most significant early collaborative projects involved the decoration of a nuptial chamber for Pierfrancesco Borgherini and Margherita Acciaiuoli, around 1515. Granacci contributed panels depicting scenes from the life of Joseph, including Joseph Presents his Father and Brothers to Pharaoh and the Arrest of Joseph (both now in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence). This prestigious commission also involved other leading Florentine artists such as Andrea del Sarto, Pontormo, and Bachiacca (Francesco Ubertini), placing Granacci firmly within the city's artistic elite. His contributions to this series showcase his narrative skill and his ability to create lively, populated scenes with a rich sense of color and detail.

Another notable work is the Entry of Charles VIII into Florence, painted around 1518 (Uffizi Gallery, Florence). This panel commemorates the French king's arrival in the city in 1494, a politically charged event. Granacci's depiction is a vibrant tableau, capturing the pageantry and historical significance of the moment. It demonstrates his capacity for handling complex compositions with numerous figures and architectural elements.

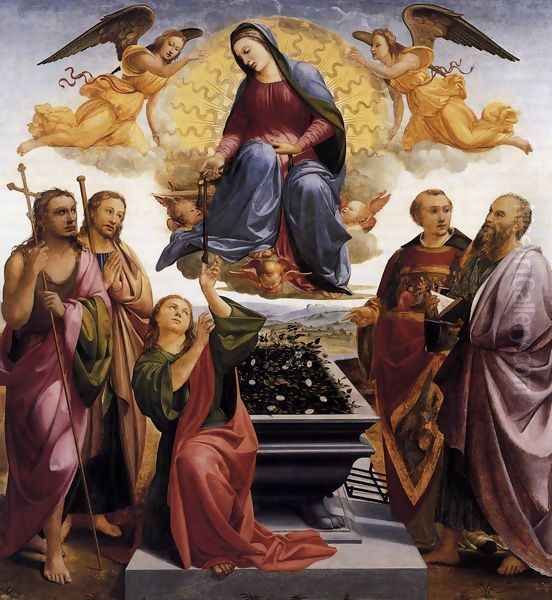

Granacci produced several important altarpieces. His Madonna of the Girdle (also known as The Assumption of the Virgin with the Madonna della Cintola, with Saints Thomas, Michael, John the Baptist, Laurence, and Bartholomew), now in the Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence, is a mature work that exemplifies his High Renaissance style. It combines monumental figures, a balanced composition, and a warm, harmonious palette, reflecting the influence of Fra Bartolomeo and Raphael. Another significant altarpiece is the Rest on the Flight into Egypt (Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence), which displays a tender intimacy and a lush landscape.

The series of panels depicting Four Histories of Saint John the Baptist (c. 1506-1507), now dispersed among various collections including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, and the Cleveland Museum of Art, are also key works. These panels, such as John the Baptist being carried to Zacharias (Metropolitan Museum of Art), are characterized by their lively narrative, expressive figures, and often intricate architectural settings. They reveal Granacci's skill in storytelling and his engagement with contemporary artistic trends.

Other important paintings include various Madonna and Child compositions, such as the Madonna and Child with Saints Francis and Zenobius (Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence, c. 1510), and devotional scenes that were popular for private patrons. The Portrait of a Man in Armour (National Gallery, London), though its attribution has been debated (sometimes given to Giuliano Bugiardini), is often associated with Granacci and showcases his abilities in portraiture, capturing a sense of individual character.

Role in Florentine Artistic and Civic Life

Beyond his individual commissions, Francesco Granacci was an active participant in the artistic and civic life of Florence. His skills were called upon for ephemeral decorations for public festivities, a common practice for Renaissance artists. A notable instance was his involvement in creating triumphal arches and other decorations for the grand entry of Pope Leo X (Giovanni de' Medici) into Florence in 1515. This was a major event for the city, and artists like Andrea del Sarto, Pontormo, Jacopo Sansovino, and Granacci collaborated to produce spectacular, albeit temporary, works of art that transformed the urban landscape. Such projects required versatility and an ability to work collaboratively under pressure.

His long career in Florence meant he was a familiar figure in the city's artistic circles. He was a member of the Compagnia di San Luca, the painters' guild, and likely participated in its activities. While he may not have run a large workshop with numerous pupils in the manner of Ghirlandaio or Andrea del Sarto, his consistent production and involvement in significant commissions ensured his respected status among his peers. His connections, particularly his enduring friendship with Michelangelo, also kept him linked to the most advanced artistic developments of his time.

The artistic environment of Florence during Granacci's lifetime was intensely competitive but also collaborative. Artists frequently shared ideas, borrowed motifs, and responded to each other's innovations. Figures like Piero di Cosimo, with his idiosyncratic mythological scenes, and Ridolfo Ghirlandaio (Domenico's son), who continued his father's workshop tradition, were also active, contributing to the rich tapestry of Florentine art. Granacci navigated this complex world, maintaining his own artistic voice while remaining open to the influences around him.

Stylistic Characteristics and Artistic Temperament

Francesco Granacci's artistic style is characterized by a synthesis of influences, resulting in a manner that is both accomplished and appealing. His figures are typically graceful and well-proportioned, often imbued with a gentle, contemplative quality. He had a fine sense of color, employing a palette that could be both rich and subtle, with a particular fondness for warm hues and harmonious combinations. His compositions are generally balanced and clearly organized, reflecting the High Renaissance concern for order and clarity, though later works sometimes show a greater complexity and dynamism, hinting at Mannerist tendencies.

Compared to the intellectual depth of Leonardo, the terribilità (awesome power) of Michelangelo, or the serene perfection of Raphael, Granacci's art might seem less revolutionary. However, his strengths lay in his consistent craftsmanship, his lyrical sensibility, and his ability to create works of quiet devotion and engaging narrative. He excelled in depicting tender interactions, such as those between the Madonna and Child, and in conveying the emotional states of his figures in a restrained yet effective manner.

His handling of drapery is often noteworthy, with flowing lines that define the underlying forms. Landscapes in his paintings, while not his primary focus, are often rendered with care, providing atmospheric settings for his figures. He was adept at integrating figures into their surroundings, whether architectural or natural. While he absorbed the lessons of sfumato from Leonardo and Fra Bartolomeo, his forms generally retain a clear definition, reflecting his Quattrocento training.

Later Years, Death, and Legacy

Francesco Granacci continued to paint into his later years, maintaining a steady output. He died in Florence on November 30, 1543, at the age of 74, a respectable lifespan for the period. He was buried in the Church of Sant'Ambrogio in Florence, a testament to his standing within the community.

In terms of direct artistic lineage, Granacci does not appear to have had a significant school of followers or prominent pupils who carried on his specific style in a major way. Unlike masters who headed large, influential workshops, his impact seems to have been more through the quality of his individual works and his role as a respected member of the Florentine artistic community. The user-provided text mentions Benozzo Gozzoli as a student, but this is chronologically impossible, as Gozzoli (c. 1421 – 1497) was a master from a previous generation, himself a student of Fra Angelico. It is more accurate to say that direct, well-documented pupils of Granacci are scarce in historical records.

His historical reputation has, to some extent, been overshadowed by his more famous contemporaries. Giorgio Vasari, in his "Lives," provides a generally positive account of Granacci, emphasizing his good nature and his friendship with Michelangelo, but perhaps not fully capturing the nuances of his artistic contributions. However, modern scholarship has increasingly recognized Granacci's merits, appreciating his skillful synthesis of Renaissance ideals and his consistent production of high-quality paintings. His works are found in major museums around the world, allowing for a broader appreciation of his talent.

The "anecdotes" surrounding him, such as the attribution debates over certain works (like the Portrait of a Man in Armour or some panels from the Life of St. John the Baptist series), highlight the complexities of connoisseurship in Renaissance art. The fact that his work could sometimes be confused with that of artists like Fra Bartolomeo or even Bugiardini speaks to the shared artistic vocabulary of the time, as well as to Granacci's ability to work in a manner that was both personal and reflective of broader trends.

Conclusion: Granacci's Place in Renaissance Art

Francesco Granacci was a quintessential Florentine painter of the High Renaissance. He navigated a period of extraordinary artistic ferment, learning from one of the leading masters of the late Quattrocento, Domenico Ghirlandaio, and forging a lifelong friendship with one of art history's giants, Michelangelo. He absorbed the innovations of Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Fra Bartolomeo, and Andrea del Sarto, integrating these influences into a style characterized by grace, harmony, and a pleasing richness of color.

His contributions to significant Florentine projects, such as the Borgherini nuptial chamber and the decorations for Pope Leo X's entry, underscore his standing within the artistic community. Works like the Madonna of the Girdle, the Entry of Charles VIII into Florence, and the Story of Joseph panels remain important examples of Florentine painting from the early to mid-16th century.

While he may not have been a radical innovator, Francesco Granacci was a highly skilled and sensitive artist who produced a consistent body of appealing and accomplished work. He represents the many talented painters who contributed to the depth and richness of the Renaissance, creating art that delighted patrons, adorned churches, and continues to be appreciated for its beauty and craftsmanship. His story is a reminder that the towering figures of art history were surrounded by a vibrant ecosystem of talented individuals who, in their own ways, shaped the artistic landscape of their time. Granacci's quiet dedication to his craft and his enduring friendships offer a valuable perspective on the human and artistic world of Renaissance Florence.