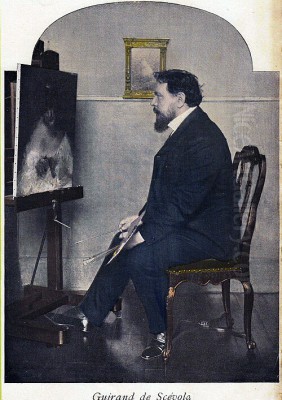

Introduction: A Painter of Two Worlds

Lucien Victor Guirand de Scévola (1871–1950) stands as a fascinating figure in French art history, a man whose career bridged the ethereal realms of Symbolism and the stark realities of modern warfare. Born in Sète, a Mediterranean port town in the south of France, Scévola initially seemed destined for a different path, working briefly in a foundry. However, his passion for art soon led him to Paris, the vibrant heart of the European art world, where he would forge a distinct artistic identity before unexpectedly becoming a key innovator in military strategy during World War I. His life and work offer a unique lens through which to view the transition from the Belle Époque's aestheticism to the brutal pragmatism demanded by global conflict.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Guirand de Scévola's journey into the art world began formally when he abandoned his work as an ironworker in Corème to pursue painting. He enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the epicenter of academic art training in France. There, he studied under notable masters, including Pierre Dupuis and, significantly, Fernand Cormon. Cormon's atelier was renowned and attracted a diverse group of students who would later make significant marks on art history, including Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Vincent van Gogh, and Émile Bernard. This environment undoubtedly exposed Scévola to a range of artistic ideas and techniques, from traditional academicism to emerging avant-garde trends.

His official debut came in 1889 when he exhibited his work for the first time at the Paris Salon, the official, state-sponsored exhibition that was still a primary venue for artists seeking recognition and patronage. This marked the beginning of a long exhibiting career. From 1894 onwards, he became a regular participant in the Salon des Artistes Français, consistently presenting his works to the Parisian public and critics. These early years were crucial in establishing his reputation and refining his artistic direction.

Embracing the Symbolist Vision

Quickly moving beyond purely academic constraints, Guirand de Scévola found his true voice within the Symbolist movement that flourished in the late 19th century. Symbolism, as a reaction against Naturalism and Realism, sought to depict not the objective world, but subjective experiences, ideas, dreams, and emotions. It favoured suggestion over description, mystery over clarity, and often drew inspiration from mythology, literature, and the inner psyche. Scévola became particularly known for his evocative portrayals of women, often depicted as ethereal, enigmatic figures – princesses, fairies, nymphs – inhabiting dreamlike settings.

His paintings from this period are characterized by a soft, often muted palette, delicate brushwork, and a masterful handling of light and shadow to create atmosphere. He shared affinities with other key Symbolist figures like Gustave Moreau, whose work often featured jewel-like details and mythological themes, and perhaps the more introspective moods found in the works of Odilon Redon or Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. Scévola's women often seem lost in thought, possessing an air of melancholy or serene detachment, embodying the Symbolist fascination with the 'femme fragile' or the mysterious feminine archetype, akin perhaps to figures found in the works of Belgian Symbolists like Fernand Khnopff.

Masterpieces of Mystery and Atmosphere

Several works exemplify Guirand de Scévola's Symbolist phase. Princesse au diadème (Princess with a Diadem), exhibited in 1897, is a quintessential example. The painting depicts a young woman, adorned with a diadem, gazing outwards with a distant, almost melancholic expression. The background features rich, decorative elements suggestive of a luxurious, perhaps historical or imaginary setting, with hints of Baroque influence in details like carvings and stained glass. The soft focus and subtle interplay of light contribute to the painting's dreamlike quality, making the princess seem both present and unreachable.

Another significant work, La Fille du Roi (The King's Daughter) from 1902, continues this exploration of idealized, almost fairy-tale femininity. Similarly, Jeune princesse médiévale (Young Medieval Princess) from 1900 places its subject within a vaguely historical, romanticized past. An earlier work, La Nuit (The Night) from 1889, showcased his early ability to capture mood and atmosphere, depicting a soft, dreamlike night scene. These paintings highlight his skill in creating intimate, psychologically charged portraits that transcend mere likeness, delving into realms of fantasy and introspection. His style often incorporated influences reminiscent of the Pre-Raphaelites in its attention to detail and romantic sensibility, yet filtered through a distinctly French Symbolist lens.

Portraiture and Society Connections

Beyond his purely Symbolist compositions, Guirand de Scévola was also an accomplished portrait painter. His skill in capturing likeness, combined with his ability to imbue his subjects with a certain elegance and psychological depth, made him sought after in certain social circles. While perhaps not as flamboyant as society portraitists like Giovanni Boldini or James Tissot, nor possessing the penetrating insight of John Singer Sargent (an American who frequently worked in Paris and London), Scévola brought his characteristic sensitivity and atmospheric touch to his portrait work.

His marriage to Marie-Thérèse Pirot further integrated him into well-connected Parisian society. These connections would prove unexpectedly crucial later in his career. His portraits often retained the soft focus and evocative lighting seen in his Symbolist works, lending even his commissioned pieces an air of refinement and subtle mystery. He navigated the line between personal artistic vision and the demands of portraiture, often choosing sitters who resonated with his aesthetic sensibilities or allowing his style to subtly shape the representation of his clients.

The Unexpected Turn: Artistry Applied to War

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 dramatically altered the course of Guirand de Scévola's life and career. Mobilized into the French army, his artistic skills soon found an entirely new, urgent application: military camouflage. While rudimentary forms of concealment had existed before, the scale and nature of warfare on the Western Front – static trench lines, aerial observation, long-range artillery – created an unprecedented need for effective visual deception. Scévola is widely credited, alongside other artists and innovators, as being one of the pioneers of modern military camouflage, or "camouflage" as the French term became internationally adopted.

Working initially with fellow artists like Eugène Corbin, a decorator from Nancy, and Louis Guignot, Scévola began experimenting with ways to disguise artillery pieces. Their early efforts involved painting cannons and covering them with painted canvas screens designed to blend into the surrounding landscape. He famously claimed to have used the principles of Cubism – the revolutionary art movement developed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque that fragmented objects and depicted them from multiple viewpoints – to "totally deform the object." The idea was not necessarily to make an object invisible, but to break up its recognizable shape and merge it with its environment, confusing enemy observation.

Leading the Camoufleurs

Recognizing the potential of these techniques, the French military command was persuaded – reportedly with the help of Scévola's societal connections through his wife – to establish a dedicated camouflage unit. In February 1915, Guirand de Scévola was appointed commander of the newly formed Section de Camouflage, headquartered initially in Amiens and later moving closer to Paris. He began recruiting other artists whose skills were suited to the task: painters, sculptors, and importantly, stage designers (décorateurs de théâtre) who were adept at creating large-scale illusions.

His team grew rapidly, eventually numbering several thousand personnel, including a core group of around 30 artists. Among those who worked as 'camoufleurs' under or alongside Scévola were notable figures from the Parisian art scene, including the Cubist painter André Mare and Jacques Villon (brother of Marcel Duchamp). These artists applied their understanding of form, colour, perspective, and illusion to a variety of military needs. They designed disruptive patterns for painting vehicles, artillery, and equipment; created fake observation posts disguised as trees or mounds of earth; developed camouflaged netting and sniper suits; and even constructed dummy installations to deceive enemy reconnaissance.

Innovation and Impact on the Battlefield

The work of the Section de Camouflage under Guirand de Scévola's leadership had a significant impact on French military operations. By concealing troop movements, supply dumps, artillery positions, and observation posts, they helped reduce casualties and provided tactical advantages. Scévola himself was known for his innovative ideas, such as proposing the use of elaborately constructed observation trees made of steel and painted canvas, allowing observers to remain hidden in seemingly natural positions close to the front lines.

His efforts did not go unrecognized. For his crucial contributions to the war effort through the development and implementation of camouflage, Guirand de Scévola was awarded the prestigious Légion d'honneur (Legion of Honour), initially as a Chevalier (Knight) and later promoted. The French system became a model, influencing the development of camouflage units in other Allied armies, such as the British efforts led by figures like Solomon J. Solomon, who also grappled with the challenges of visual deception in modern warfare. Scévola's role cemented an unexpected but profound link between avant-garde artistic theory and military necessity.

Later Career and Artistic Legacy

After the war, Guirand de Scévola returned to his artistic career, though forever marked by his wartime experiences. He continued to paint, primarily focusing on portraits and decorative works, often maintaining the soft, atmospheric style that had characterized his earlier Symbolist period. His reputation, enhanced by his wartime service and his established position in the art world, remained strong. He continued to exhibit his work and became an influential figure in French art institutions.

He served as President of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, one of the main exhibiting societies in Paris, demonstrating his respected status within the artistic community. While the avant-garde continued its relentless march towards abstraction and new forms of expression, Scévola largely remained true to his established aesthetic, providing a link back to the elegance and introspection of the pre-war era. His work continued to find admirers who appreciated his technical skill and the enduring appeal of his refined, often dreamlike imagery.

Despite his artistic and military achievements, sources suggest his personal life may have had its share of difficulties, though details remain scarce, described simply as "unfortunate" in some accounts. He passed away in Paris in 1950 at the age of 79, leaving behind a dual legacy: that of a sensitive Symbolist painter who captured the ephemeral beauty and mystery of his time, and that of a pragmatic innovator who harnessed the power of art for the grim necessities of war.

Conclusion: Bridging Art and Utility

Lucien Victor Guirand de Scévola occupies a unique niche in the history of French culture. As an artist, he was a significant participant in the Symbolist movement, contributing a body of work characterized by its delicate beauty, atmospheric depth, and focus on enigmatic femininity. His paintings offer a window into the fin-de-siècle fascination with dreams, myths, and the inner world. He stood alongside contemporaries like Moreau, Redon, and Khnopff in exploring alternatives to realism, seeking a more poetic and suggestive form of expression.

Simultaneously, his unexpected role as a pioneer of military camouflage during World War I highlights the surprising intersections that can occur between art and other fields. His application of artistic principles, potentially inspired by Cubism, to the practical problem of military concealment demonstrates remarkable adaptability and ingenuity. Leading the 'camoufleurs', he not only contributed significantly to the French war effort but also helped establish a new field that continues to be relevant today. Guirand de Scévola's life reminds us that creativity can manifest in diverse ways, bridging the seemingly disparate worlds of aesthetic contemplation and practical application, the gallery and the battlefield.