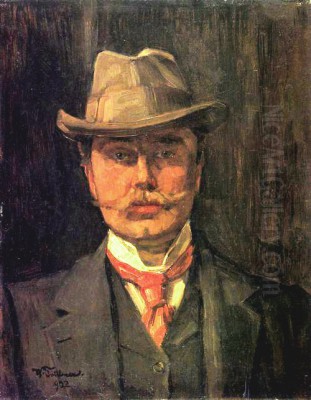

Wilhelm Trübner stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of 19th and early 20th-century German art. A painter of remarkable versatility, his career navigated the currents of Realism, Naturalism, and Impressionism, while also touching upon Symbolism and laying groundwork for modern artistic thought. His commitment to the principle of "art for art's sake" and his exploration of "pure painting" marked him as a forward-thinking artist, whose influence extended through his own prolific output and his dedicated work as an educator. This exploration delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of Wilhelm Trübner, examining his artistic development, his key relationships, and his contributions to the rich tapestry of German art history.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Heidelberg

Heinrich Wilhelm Trübner was born on February 3, 1851, in the historic university city of Heidelberg, located in the Grand Duchy of Baden (now Baden-Württemberg), Germany. His father was a master goldsmith, and young Wilhelm initially followed in his footsteps, beginning an apprenticeship in the family trade. This early training in a craft demanding precision and attention to material qualities may have subtly informed his later approach to painting, particularly his sensitivity to texture and form.

The pivotal moment that redirected Trübner's path towards fine art occurred in 1867. It was then that he encountered the work of Anselm Feuerbach, a leading German classical painter of the era. Feuerbach's idealized figures and historical themes, though stylistically different from Trübner's eventual direction, ignited a passion for painting in the young man. Inspired, Trübner made the decisive choice to abandon his goldsmithing career and pursue formal artistic training. He enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Karlsruhe that same year, marking the official commencement of his journey into the art world. His time in Karlsruhe provided him with foundational skills, but his artistic vision would soon be shaped by more radical influences.

The Munich Years: The Leibl Circle and the Embrace of Realism

In 1868, Trübner moved to Munich, a vibrant artistic hub that was then challenging the dominance of more conservative art centers. He enrolled in the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, where he studied under Alexander von Wagner, a painter known for his historical and genre scenes. However, it was outside the formal academy structure that Trübner found his most profound artistic nourishment. The 1869 International Art Exhibition in Munich proved to be a watershed event. It was here that Trübner, along with many other German artists, was exposed to the groundbreaking realism of French painters Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet.

Courbet's unvarnished depictions of everyday life and his robust, tactile paint application, alongside Manet's bold compositions and modern subject matter, offered a powerful alternative to the prevailing academic idealism. These encounters deeply impacted Trübner. He became particularly fascinated by Courbet's concept of "pure painting," which emphasized the intrinsic qualities of the paint and the act of painting itself, rather than solely focusing on the narrative or symbolic content of the subject. This idea would become a cornerstone of Trübner's own artistic philosophy.

During this period, Trübner met Wilhelm Leibl, another German artist profoundly influenced by Courbet. Leibl was a charismatic figure and a leading proponent of Realism in Germany. Trübner, along with other like-minded young artists such as Carl Schuch, Hans Thoma, and Albert Lang, gravitated towards Leibl, forming an informal group that came to be known as the "Leibl-Kreis" (Leibl Circle). This circle became a crucible for the development of German Realism. They shared a commitment to direct observation, a rejection of sentimentalism, and an interest in capturing the unadorned truth of their subjects, whether portraits, landscapes, or still lifes. The influence of 17th-century Dutch masters, with their meticulous detail and subtle handling of light, was also a shared touchstone for the group.

Trübner's works from this early Munich period, such as The Girl on the Sofa (1872) and Moor Reading the Newspaper (1873) (also known by its German title, Neger mit Zeitung), demonstrate his rapid assimilation of Realist principles. These paintings are characterized by their sober palettes, strong chiaroscuro, and a focus on capturing the psychological presence of the sitter or the quiet dignity of an everyday scene. He sought to render form and texture with honesty, allowing the materiality of the paint to contribute to the overall effect.

Travels and Broadening Artistic Horizons

The 1870s were a period of significant travel and artistic exploration for Trübner, further broadening his perspectives. He journeyed extensively, visiting Italy, Holland, and Belgium. These trips exposed him to a wider range of artistic traditions, from the Italian Renaissance masters to the Dutch Golden Age painters like Frans Hals and Rembrandt, whose vigorous brushwork and psychological depth resonated with his own artistic aims.

A particularly influential destination was Paris. His encounters with the burgeoning Impressionist movement, and especially the work of Édouard Manet, continued to shape his development. While Trübner never fully adopted the broken brushwork or the scientific color theories of the core Impressionists, he absorbed their emphasis on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light, and a more modern sensibility in subject matter. Manet's bold compositions, flattened perspectives, and sophisticated use of black as a color found echoes in Trübner's evolving style.

These travels enriched his thematic repertoire. While portraiture remained a significant genre for him, he increasingly turned to landscape painting. His landscapes from this period often depict scenes from his travels or the German countryside, rendered with a keen eye for atmospheric effects and a solid, almost sculptural sense of form. He was less interested in the picturesque than in conveying the underlying structure and character of the land.

His mythological and historical paintings also began to take on a new character. Works like Battle of the Giants (1876-1877) show a departure from the strict Realism of the Leibl Circle, incorporating more dynamic compositions and a heightened sense of drama, though still grounded in a powerful physicality. This period marked a growing independence in Trübner's artistic vision, as he began to synthesize the various influences he had absorbed into a more personal style.

Artistic Philosophy: "Art for Art's Sake" and Theoretical Writings

Wilhelm Trübner was not only a practicing artist but also a thoughtful theorist. He articulated his artistic philosophy in several writings, notably in publications from 1892 and 1898. Central to his thinking was the concept of "Das reine Malen" (pure painting) and the principle of "l'art pour l'art" (art for art's sake). He famously stated, "Beauty must be found in the painting itself, not in the subject."

This philosophy posited that the aesthetic value of a work of art resides primarily in its formal qualities—color, line, composition, texture—rather than in its narrative, moral, or historical content. For Trübner, the subject was merely a pretext for exploring these formal elements. This was a radical stance in a German art world still largely dominated by academic traditions that prioritized subject matter and didactic purpose. His ideas aligned him with international avant-garde movements that sought to liberate art from its traditional illustrative and storytelling functions.

However, Trübner's theoretical pronouncements sometimes appeared to be at odds with his own artistic practice. While he championed form over content, he continued to paint historical, mythological, and literary subjects throughout his career. This apparent contradiction has been a point of discussion among art historians. Some see it as an unresolved tension in his work, while others suggest that even in his more traditional subjects, his primary concern remained the painterly problems they presented. For instance, a mythological scene could offer opportunities for complex figure arrangements, dramatic lighting, and rich color harmonies, all of which served his exploration of "pure painting."

His views on photography were also noteworthy for the time. He recognized photography's potential but argued for a clear distinction between its documentary function and the creative, interpretive role of painting. He believed that photography could serve art but should not dictate its aims, a perspective that reflected the broader anxieties and debates among painters regarding the rise of this new medium.

The Frankfurt Period: Teaching and Continued Development

After his intensive period of travel and early success in Munich, Trübner's career took him to Frankfurt am Main. From 1895 or 1896, he taught at the Städel Art Institute, one of Germany's most prestigious art schools. His role as an educator became an important facet of his career. He also established his own private painting school in Frankfurt, which notably catered to female students, offering them opportunities for artistic training that were not always readily available in the more traditional, male-dominated academies.

One of his students from this period was Alice Auerbacher, who, after studying with Trübner around 1897, went on to open her own art school. This demonstrates Trübner's influence extending to the next generation of artists, including women seeking professional careers in art. His teaching likely emphasized the principles of direct observation and strong formal construction that were central to his own work.

During his Frankfurt years, Trübner continued to produce a diverse body of work. His portraits remained highly sought after, and he continued to explore landscape and still life. He was also a founding member of the "Frankfurt-Cronberg Künstlerbund" (Frankfurt-Cronberg Artists' Association), indicating his active participation in the local art scene and his commitment to fostering a supportive community for artists. His work Burg Kronberg im Taunus (Castle Kronberg in the Taunus) reflects his engagement with the local landscape.

His style during this period continued to evolve. While the foundations of Realism remained, there was often a greater emphasis on decorative qualities and a more nuanced exploration of color and light, perhaps reflecting a subtle absorption of Post-Impressionist ideas. Works like Pomona (1898) blend realistic depiction with a certain Art Nouveau sensibility in their rhythmic lines and decorative arrangement.

The Karlsruhe Professorship and Later Years

In 1903, Trübner was appointed professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Karlsruhe, the same institution where he had begun his studies. He would remain associated with the Karlsruhe Academy for the rest of his active career, eventually becoming its director from 1904 to 1910. This appointment solidified his status as a leading figure in German art education.

His commitment to progressive artistic ideas was further demonstrated by his involvement with the Berlin Secession, which he joined in 1901. The Berlin Secession, led by artists like Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt, was a vital organization that championed modern art in Germany, breaking away from the conservative establishment of the official Salon. Trübner's association with the Secession placed him firmly within the modernist camp, alongside artists who were embracing Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and other new artistic currents.

In his later years, Trübner increasingly focused on landscape painting. He developed a particular interest in depicting the same motifs under different light and weather conditions, or from slightly varied perspectives, a practice reminiscent of Claude Monet's series paintings. His landscapes from this period, such as Lake Starnberg (1911), are often characterized by simplified forms, bold color harmonies, and a strong sense of design. Some art historians have noted a resemblance in this approach to the compositional strategies of Japanese Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, with their flattened spaces and decorative patterning.

This late style, with its emphasis on simplification and the expressive potential of color and form, can be seen as a culmination of his lifelong pursuit of "pure painting." However, this shift was not universally acclaimed; some critics perceived it as a regression or a narrowing of his artistic scope.

Trübner's health began to decline in his later years. In 1917, he was offered a prestigious professorship at the Berlin Academy of Arts but had to decline due to ill health. Wilhelm Trübner passed away on December 21, 1917, in Karlsruhe, the city where his artistic journey had begun and where he had spent his final productive years as a respected artist and teacher.

Key Artistic Influences and Stylistic Evolution

Trübner's artistic journey was marked by a continuous absorption and synthesis of diverse influences. His initial inspiration came from the classicism of Anselm Feuerbach, but this was quickly superseded by the powerful Realism of Gustave Courbet. Courbet's emphasis on the tangible, the unidealized, and the materiality of paint itself became a foundational element of Trübner's approach.

The association with Wilhelm Leibl and the Leibl Circle (including Carl Schuch, Hans Thoma, and Albert Lang) further solidified his commitment to Realist principles, drawing also on the meticulous observation and technical mastery of 17th-century Dutch painters like Frans Hals and Rembrandt van Rijn. The dark tonalities and psychological depth of these masters are evident in Trübner's early portraits and genre scenes.

Édouard Manet was another crucial influence, particularly Manet's modern sensibility, his bold use of black, and his ability to capture contemporary life with a certain detachment and elegance. While Trübner did not become an Impressionist in the French mold, he shared with artists like Manet and Edgar Degas an interest in capturing the visual realities of the modern world, often with a focus on strong composition and form.

The influence of the Spanish master Diego Velázquez, with his sophisticated use of color, particularly blacks and grays, and his ability to convey both regal presence and intimate humanity, can also be discerned in Trübner's portraiture. Trübner, like many artists of his generation, admired Velázquez's painterly freedom and his mastery of representation.

His stylistic evolution can be traced from the robust, somewhat dark Realism of his early Munich period, heavily indebted to Courbet and Leibl. This gradually lightened and became more nuanced through his travels and exposure to Impressionistic ideas, leading to a greater emphasis on atmospheric effects and a broader palette in his landscapes and some portraits.

The 1870s also saw him explore more imaginative and symbolic themes, as in Gorgon's Head (also referred to as Sphinx Head), a work that delves into Symbolist territory with its enigmatic subject and evocative mood. This piece, with its powerful female figure, showcases a departure from strict naturalism towards a more suggestive and psychologically charged art.

In his later career, particularly in his landscapes, Trübner moved towards a more simplified, almost decorative style. Forms became flatter, colors bolder and more harmonized, and compositions often emphasized pattern and design. This late phase, while rooted in observation, prioritized the autonomous, aesthetic qualities of the painting, bringing his career full circle to his early commitment to "pure painting." His work, therefore, forms a bridge between 19th-century Realism and the emerging concerns of 20th-century modernism, where form and color would increasingly assert their independence from purely representational aims. Other contemporaries who were part of the broader shift in German art included figures like Max Klinger, known for his Symbolist works, and the leading German Impressionists Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt, with whom Trübner shared an affiliation through the Berlin Secession.

Representative Masterpieces: A Closer Look

Wilhelm Trübner's oeuvre is extensive, but several works stand out as particularly representative of his artistic concerns and stylistic development.

_The Girl on the Sofa_ (1872): An early masterpiece from his Leibl Circle period, this painting exemplifies the "pure painting" ideal. The subject, a young woman reclining pensively, is rendered with a sober palette and a focus on the interplay of light and shadow. The textures of fabric and flesh are palpable, and the composition is simple yet powerful, conveying a sense of quiet introspection.

_Moor Reading the Newspaper_ (1873): This work, also from his early Munich phase, showcases Trübner's skill in portraiture and his interest in capturing everyday subjects with dignity. The painting is notable for its strong modeling of form and its sensitive depiction of the subject's concentration. The dark tonalities are characteristic of the Leibl Circle's aesthetic.

_Gorgon's Head_ (or _Sphinx Head_) (c. 1870s-1880s): This painting marks a foray into Symbolist themes. The enigmatic and powerful female head, with its direct gaze, evokes ancient mythology and the femme fatale archetype popular in late 19th-century art. The handling is still robustly painterly, but the subject matter moves beyond straightforward Realism into a more imaginative realm.

_Battle of the Giants_ (1876-1877): This work demonstrates Trübner's engagement with mythological subjects, but rendered with a Realist's attention to anatomy and physical force. It represents a period where he sought to apply his painterly skills to more dynamic and complex compositions.

_Burg Kronberg im Taunus_ (various versions): Trübner painted Castle Kronberg and its surroundings multiple times, particularly during his Frankfurt period. These landscapes showcase his ability to capture the specific character of a place, often with a solid, almost architectural rendering of form, combined with an increasing sensitivity to atmospheric light.

_Lake Starnberg_ (1911): Representative of his later landscape style, this painting features simplified forms, a brighter palette, and a focus on harmonious color relationships. The scene of the lake and its shores is distilled into essential shapes and planes of color, reflecting his late interest in the decorative and formal aspects of painting, possibly influenced by Japanese art.

_Pomona_ (1898): This work depicts the Roman goddess of fruit trees. It blends a realistic portrayal of the female figure with a decorative, almost Art Nouveau sensibility in the arrangement of fruit and foliage, showcasing his stylistic versatility at the turn of the century.

These works, among many others, illustrate Trübner's journey through different artistic modes, his consistent emphasis on strong painterly qualities, and his ability to imbue diverse subjects with a distinct and powerful presence.

Relationships with Contemporaries: Cooperation and Individuality

Trübner's career was deeply intertwined with the artistic currents and personalities of his time. His most significant early collaborative relationship was within the Leibl Circle. With Wilhelm Leibl, Carl Schuch, Hans Thoma, and Albert Lang, he shared a commitment to Realism and a mutual respect for technical skill and honest observation. They often worked in close proximity, influenced each other's development, and provided a supportive network in their challenge to academic conventions. For instance, Trübner traveled and painted alongside Schuch and Thoma in the early 1870s, a period of shared artistic exploration.

Despite these close ties, Trübner maintained a strong sense of artistic independence. While Leibl, for example, remained more consistently devoted to a meticulous, almost Holbein-esque Realism, Trübner's path was more varied. He was more open to absorbing influences from French art, particularly Manet, and his theoretical leanings towards "art for art's sake" set him somewhat apart, even from his Leibl Circle colleagues. His exploration of mythological and historical themes also distinguished him from the more purist Realism of some of his peers.

His relationship with the broader German art world was complex. He was respected as a painter and teacher, as evidenced by his professorships in Frankfurt and Karlsruhe and his eventual directorship of the Karlsruhe Academy. His participation in the Berlin Secession alongside figures like Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt aligned him with the progressive forces in German art. These artists, while stylistically diverse, shared a common goal of promoting modern artistic expression free from the constraints of the official art establishment.

However, Trübner's staunch individualism and his sometimes-uncompromising artistic principles could also lead to a degree of isolation. His later stylistic shifts, particularly his move towards simplified landscapes, were not always understood or appreciated by all his contemporaries. Nevertheless, he remained a significant presence, a painter who consistently forged his own path while engaging with the major artistic debates of his era. His influence on younger artists, both through his teaching and his example, was considerable, even if he did not found a "school" in the way Leibl did.

Legacy and Impact on German Art

Wilhelm Trübner's legacy is that of a transitional figure who played a crucial role in steering German art from 19th-century academic traditions towards a more modern understanding of painting. His early embrace of Realism, inspired by Courbet and nurtured within the Leibl Circle, helped to establish a powerful alternative to the prevailing idealism and narrative painting.

His most enduring contribution, perhaps, lies in his advocacy for "pure painting" and "art for art's sake." By championing the autonomous aesthetic qualities of the artwork—its color, form, and texture—over its subject matter, Trübner anticipated key developments in 20th-century modernism, where abstraction and formal experimentation would come to the fore. While Trübner himself never abandoned representation, his theoretical stance provided a crucial intellectual underpinning for artists who would later push the boundaries of painting even further.

As an educator at the Städel Institute and the Karlsruhe Academy, he influenced a generation of students, instilling in them a respect for craftsmanship, direct observation, and artistic integrity. His willingness to teach female artists in his private school also marked him as relatively progressive for his time.

Today, Trübner's works are held in major German museums, including the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, and the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe. While he may not enjoy the same international household-name recognition as some of his French contemporaries like Monet or Renoir, or even German Impressionists like Liebermann, his importance within the context of German art history is undeniable. He is recognized as a master of Realism, a sensitive portraitist, an innovative landscape painter, and a thoughtful theorist whose ideas resonated with the burgeoning modernist spirit.

Conclusion: An Enduring Voice in German Art

Wilhelm Trübner's artistic journey was one of constant exploration and a steadfast commitment to the integrity of the painted image. From his early immersion in the robust Realism of the Leibl Circle to his later, more simplified and formally focused landscapes, he consistently sought to realize his vision of "pure painting." He navigated the complex artistic landscape of his time, absorbing influences from Dutch Old Masters, French Realists, and Impressionists, yet always forging a distinctly personal style.

His theoretical contributions, particularly his emphasis on the autonomy of art, were forward-looking and provided a crucial bridge to modernist aesthetics. As a painter, his technical skill, his profound understanding of color and form, and his ability to capture the essence of his subjects—be they people, landscapes, or mythological scenes—mark him as a significant talent.

Though sometimes overshadowed by other figures, Wilhelm Trübner remains a pivotal artist in the narrative of German art, a painter whose dedication to his craft and his progressive ideas helped to shape the course of modern painting in Germany. His work continues to reward close study, revealing a complex and deeply thoughtful artist whose contributions resonate to this day.