Bartolomeo Bettera (1639–c. 1688/1699) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of Italian Baroque art. A native of Bergamo, a city with a vibrant artistic tradition, Bettera carved a distinct niche for himself as a painter of still lifes, particularly those celebrating the world of music. His canvases, often laden with meticulously rendered musical instruments, books, and other symbolic objects, offer a window into the cultural preoccupations, aesthetic sensibilities, and intellectual currents of 17th-century Lombardy. While his fame was somewhat eclipsed by his master, Evaristo Baschenis, and his works occasionally misattributed, modern scholarship has increasingly recognized Bettera's unique contributions, his technical skill, and the subtle complexities embedded within his compositions.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in Bergamo

Born in Bergamo in 1639, Bartolomeo Bettera emerged during a period when the city was a flourishing center for still-life painting. This genre, which gained enormous popularity across Europe in the 17th century, found a particular expression in Northern Italy, often imbued with a sense of Lombard realism and a penchant for intricate detail. The young Bettera's artistic path was decisively shaped by his apprenticeship under Evaristo Baschenis (1617–1677), the pre-eminent master of musical still life in Bergamo and arguably one of the most innovative still-life painters in Italy.

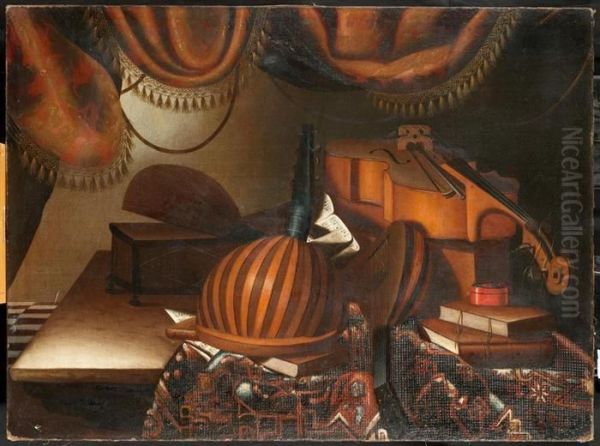

Baschenis, himself a priest and a painter, was renowned for his almost sculptural arrangements of lutes, violins, mandolins, and keyboard instruments, often artfully strewn with ribbons, sheet music, and sometimes covered in a delicate layer of dust, hinting at the passage of time and the vanitas theme – the transience of earthly pleasures and pursuits. From Baschenis, Bettera inherited a profound understanding of perspective, a mastery of chiaroscuro (the dramatic use of light and shadow), and an unwavering commitment to rendering the textures and forms of his subjects with verisimilitude. The tactile quality of polished wood, the sheen of varnish, the crispness of paper, and the softness of velvet draperies are all palpable in the works of both master and pupil.

Development of a Personal Style

While deeply indebted to Baschenis, Bartolomeo Bettera was not a mere imitator. He absorbed his master's lessons and gradually forged a style that, while sharing a common thematic ground, possessed its own distinct characteristics. Bettera's compositions often exhibit a greater tendency towards decorative richness and a more overtly theatrical presentation. If Baschenis's works sometimes convey a melancholic introspection, Bettera's can feel more opulent and celebratory, though still retaining an underlying symbolic depth.

His arrangements are often more crowded, featuring a profusion of objects that fill the canvas. He frequently incorporated elaborate draperies, often rich velvets or patterned carpets, which cascade across tables and serve as a sumptuous backdrop for the primary subjects. These textiles, with their complex folds and vibrant colors, add a dynamic and sensuous quality to his paintings. Furthermore, Bettera's lighting, while rooted in the chiaroscuro tradition, could be more dramatic, highlighting specific elements to create focal points and guide the viewer's eye through the complex arrangements. This theatricality aligns with the broader aesthetics of the High Baroque, which favored dynamism, emotional intensity, and grandeur.

Thematic Concerns and Symbolism

The central theme in Bettera's oeuvre, as with Baschenis, is music. Musical instruments are not merely decorative props; they are imbued with layers of meaning. In the 17th century, music was considered one of the liberal arts, closely linked to mathematics and cosmology. It was seen as a reflection of divine harmony and a powerful means of expressing human emotion. The depiction of instruments could celebrate the ennobling power of music, its capacity to elevate the human spirit, and its role in social and cultural life.

Often accompanying the instruments are books, sheet music, and occasionally globes or scientific instruments. These elements can signify learning, intellectual pursuit, and the broader world of human knowledge. However, the still-life genre, particularly in the Baroque period, was frequently infused with vanitas symbolism. The beautiful, meticulously rendered objects – symbols of human achievement and pleasure – also served as reminders of the fleeting nature of life, the inevitability of death, and the ephemeral quality of worldly possessions and accomplishments. The silent instruments, the closed books, the snuffed candles (though less common in Bettera than in some Northern European still lifes) could all allude to this underlying theme. The very stillness of the "still life" (Italian: natura morta, or "dead nature") inherently carries this connotation.

Representative Works

Several paintings exemplify Bartolomeo Bettera's artistic vision and technical prowess. Among his most characteristic is "Still Life with Musical Instruments." Typically, such a work would feature an array of stringed instruments like lutes, guitars, and violins, perhaps a cello, alongside wind instruments or a spinet. These are often artfully arranged on a table covered with a rich, patterned carpet or a velvet cloth. Open books of music, a globe, or perhaps an inkwell and quill might complete the composition. The interplay of light and shadow would define the forms, highlighting the polished wood of the instruments and the intricate details of their construction. The overall effect is one of controlled abundance and sophisticated elegance.

Another notable, though perhaps less common, subject is seen in works like the attributed "Still Life with Parrot." While musical instruments often remain central, the inclusion of an exotic bird like a parrot adds another layer of meaning and visual interest. Parrots, in the 17th century, were symbols of wealth, exoticism, and sometimes, in a religious context, could allude to the Virgin Mary or the Annunciation (as mimics of the human voice). Their vibrant plumage also offered the artist an opportunity to display their skill in rendering color and texture.

The influence of Baschenis is evident, but Bettera often pushes the compositions towards a greater density and a more pronounced decorative flair. His works are less about the quiet poetry of dust and silence found in some of Baschenis's paintings and more about the celebration of material beauty and artistic skill, albeit still underpinned by the prevalent vanitas undertones of the era.

Life in Milan and Later Career

Historical records indicate that Bartolomeo Bettera's career was not confined to Bergamo. Around 1677, he is documented as having moved to Milan, a larger and more cosmopolitan artistic center. This move likely offered him new patronage opportunities and exposure to a wider range of artistic influences. Milan, under Spanish rule for much of the 17th century, had its own distinct artistic traditions, though Lombard naturalism remained a strong current. Painters like Daniele Crespi (c. 1598–1630), though from an earlier generation, had established a powerful realist tradition. The legacy of Caravaggio (1571–1610), who had spent his formative years in Lombardy, continued to resonate, particularly his dramatic use of chiaroscuro and his unidealized depiction of reality.

In Milan, Bettera continued to produce still lifes, presumably adapting his style to the tastes of his new clientele while retaining his signature focus on musical themes. The exact duration of his activity in Milan and the precise date of his death are subject to some scholarly debate. Some sources suggest he died around 1688, while others propose a later date, possibly as late as 1699. This uncertainty is not uncommon for artists of this period, especially those who were not of the absolute first rank of fame in their own lifetime.

The Bettera Family and Artistic Lineage

Bartolomeo Bettera was not the only painter in his family. His son, Bonaventura Bettera (active late 17th – early 18th century), followed in his father's footsteps, also specializing in still-life paintings, particularly those featuring musical instruments. Bonaventura's style is often described as being even more decorative and perhaps less analytical than his father's, reflecting the evolving tastes of the late Baroque and early Rococo periods. The works of father and son have sometimes been confused, further complicating attributions.

It is important to address a point of potential confusion that appears in some sources. The provided information mentions Bartolomeo Bettera as the father of Ruggiero Boscovich, the famous 18th-century philosopher and scientist, and attributes literary activities such as writing poetry and defending the Croatian language to him. However, this appears to be a conflation with a different Bettera family, likely of Dalmatian origin. Ruggiero Boscovich (Ruđer Bošković, 1711–1787) was born in Ragusa (Dubrovnik). His father was Nikola Bošković, and his mother was Paola Bettera, daughter of a local merchant named Baro Bettera, who was indeed a poet and wrote in Croatian. While the painter Bartolomeo Bettera was a contemporary of Baro Bettera's father, there is no established connection making the painter the father of Ruggiero Boscovich or the author of the Ragusan literary works. Such conflations can occur over time, especially with shared surnames across different regions and professions. The primary and well-documented identity of Bartolomeo Bettera is that of a painter from Bergamo.

Similarly, the mention of his wife being Maria Agostini from a wealthy Venetian merchant family is more likely associated with the Ragusan Bettera lineage connected to the Boscovich family, given their mercantile connections in the Adriatic. Documented details about the painter Bartolomeo Bettera's personal life, beyond his artistic career and his son Bonaventura, remain relatively scarce.

Contemporaries and the Broader Context of Still Life

To fully appreciate Bettera's contribution, it is useful to consider him within the broader context of Italian and European still-life painting. In Italy, besides Baschenis, other artists were exploring the still-life genre with distinct regional characteristics. In Naples, painters like Paolo Porpora (1617–1673), Giuseppe Recco (1634–1695), and Giovanni Battista Ruoppolo (1629–1693) created lush, often dramatic compositions of fish, fruit, and flowers, characterized by rich colors and dynamic arrangements. The Roman school included artists like Michelangelo Pace, known as "Campidoglio" (c. 1610–c. 1670), and Mario Nuzzi, called "Mario de' Fiori" (1603–1673), who specialized in opulent floral pieces.

Further north, the influence of Flemish and Dutch still-life painting was also felt. Artists like Abraham Brueghel (1631–1697), a Fleming who worked extensively in Italy, brought a Northern European sensibility for detail and rich textures. The Dutch "pronkstilleven" (ostentatious still life) painters such as Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606–1684) and Willem Kalf (1619–1693) created lavish displays of luxury goods that resonated with wealthy patrons across Europe. Even in Spain, masters like Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664) and later Juan van der Hamen y León (1596-1631) produced still lifes of profound simplicity and spiritual intensity. While Bettera's work is firmly rooted in the Bergamesque tradition, it participates in this wider European fascination with the material world and its symbolic representation. The meticulous rendering of objects, whether humble or luxurious, reflected a growing interest in empirical observation, a hallmark of the scientific revolution that was unfolding concurrently.

Other Italian still-life painters of note from the period, or slightly earlier, who contributed to the genre's development include Fede Galizia (1578–1630), one of the earliest Italian women to gain recognition as a still-life painter, known for her precise and balanced compositions of fruit. Giovanna Garzoni (1600–1670) was another prominent female artist, celebrated for her delicate still lifes on vellum, often depicting fruit, vegetables, and insects with scientific accuracy. Later, Cristoforo Munari (1667–1720) would continue the tradition of elaborate still lifes, often featuring musical instruments, books, and porcelain, bridging the late Baroque and Rococo.

Attribution, Recognition, and Legacy

For a considerable period, Bartolomeo Bettera's works were often subsumed under the name of his more famous master, Evaristo Baschenis, or simply attributed to the "School of Baschenis." This is a common fate for talented pupils whose style closely aligns with that of their teachers. However, art historical scholarship, particularly from the late 19th century onwards, began to disentangle their respective oeuvres. Close stylistic analysis, attention to compositional preferences, and the occasional signed or documented work have allowed experts to identify Bettera's individual hand with greater confidence.

His paintings are now found in various European museums and private collections, testament to a renewed appreciation for his skill. While he may not have achieved the widespread fame of some of his contemporaries during his lifetime, his contribution to the specific subgenre of musical still life is undeniable. He successfully carried forward the tradition established by Baschenis, infusing it with his own sensibility for decorative richness and theatrical arrangement.

Bettera's influence can be seen in the continuation of the musical still-life tradition in Lombardy and beyond. His works, and those of Baschenis, helped to establish musical instruments as a compelling and symbolically rich subject for still-life painters. The precision of their renderings also provides valuable iconographic information for musicologists studying historical instruments. The shift towards cooler palettes and perhaps a more overtly decorative quality in some of his later works, or those of his son Bonaventura, can also be seen as anticipating the changing aesthetic tastes of the 18th century, moving away from the dramatic intensity of the High Baroque towards the lighter, more graceful sensibilities of the Rococo.

Conclusion: An Enduring Harmony

Bartolomeo Bettera remains a fascinating figure in the history of Italian still-life painting. As a skilled practitioner from Bergamo, he masterfully captured the allure of musical instruments, transforming them into potent symbols of art, intellect, and the ephemeral nature of human existence. Working in the shadow of his master Evaristo Baschenis, he nevertheless developed a distinct artistic voice characterized by a heightened sense of decoration, a rich palette, and complex, engaging compositions.

His dedication to the genre, particularly his focus on musical themes, contributed significantly to the vibrancy of still-life painting in 17th-century Lombardy. While some biographical details remain elusive and historical accounts have occasionally conflated him with other individuals sharing his surname, his artistic legacy is secure. The canvases of Bartolomeo Bettera continue to resonate, offering a harmonious blend of technical virtuosity, intellectual depth, and the enduring beauty of objects that speak silently of culture, time, and the timeless allure of music. His works invite contemplation, not just of the objects depicted, but of the rich cultural milieu from which they emerged, ensuring his place within the intricate and captivating narrative of Baroque art.