Antonio Gianlisi (1677–1727) stands as a notable figure in the rich tapestry of Italian Baroque art, a painter whose canvases brim with the opulence and meticulous detail characteristic of the Lombard school of still life painting. Born in Cremona, a city renowned for its artistic and musical heritage, Gianlisi carved a niche for himself by specializing in natura morta, or still life, a genre that allowed him to explore the interplay of texture, light, and composition with remarkable skill. His works, often featuring sumptuous arrangements of fruits, flowers, elaborate textiles, and occasionally musical instruments or animals, reflect both the prevailing artistic currents of his time and a distinct personal vision. Though aspects of his artistic identity have been subject to scholarly discussion, the enduring quality and distinctive charm of his paintings affirm his place among the significant still life painters of the late 17th and early 18th centuries in Italy.

The Lombard Context and Artistic Formation

Antonio Gianlisi's artistic journey began in Cremona, a city in Lombardy that, while perhaps more famous for its violin makers like Stradivari and Amati, also possessed a vibrant artistic environment. The Lombard school of painting, particularly in the realm of still life, had developed a strong tradition of naturalism, a legacy stretching back to Caravaggio's revolutionary approach to realism in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. This naturalistic impulse was often combined with a penchant for intricate detail and a celebration of material abundance, traits that would become hallmarks of Gianlisi's own work.

While specific details about Gianlisi's formal training and early influences remain somewhat elusive, his style clearly aligns him with the followers of Evaristo Baschenis (1617–1677), a Bergamasque painter celebrated for his sophisticated still lifes of musical instruments. The "Scuola di Lorenzo," or Lorenzo School, mentioned in relation to Gianlisi, likely refers to this tradition, possibly stemming from a historical misattribution or a regional term for Baschenis's stylistic impact. Baschenis and his followers, such as Bartolomeo Bettera (c. 1639 – c. 1699), were masters at rendering the polished wood of lutes and violins, the sheen of silk, and the complex patterns of oriental rugs, creating compositions that were both visually stunning and intellectually engaging. Gianlisi absorbed these influences, adapting them to his own thematic preferences.

The broader artistic climate of Italy during Gianlisi's formative years was dominated by the High Baroque, a style characterized by dynamism, emotional intensity, and a flair for the dramatic. While Gianlisi's chosen genre of still life might seem more subdued than the grand historical or religious narratives of painters like Luca Giordano (1634–1705) or Carlo Maratta (1625–1713), the Baroque sensibility is nonetheless evident in the richness of his compositions, the theatrical arrangement of objects, and the often-luxurious quality of the items depicted. His work can be seen as part of a wider European fascination with still life, a genre that flourished in the Netherlands with masters like Willem Kalf (1619–1693), whose opulent pronkstilleven share a similar delight in rendering precious objects, and in Spain with painters such as Juan Sánchez Cotán (1560–1627) and Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664), known for their austere yet powerful still lifes.

Characteristics of Gianlisi's Art: Naturalism and Baroque Flourish

Antonio Gianlisi's artistic signature is deeply rooted in the Lombard tradition of naturalism, yet it is infused with a distinct Baroque exuberance. His paintings are meticulous studies of form, texture, and light, capturing the tangible reality of the objects he chose to depict. This naturalism, however, is not merely an exercise in verisimilitude; it serves to heighten the sensory appeal of his compositions, inviting the viewer to almost touch the velvety skin of a peach or the cool smoothness of a porcelain vase.

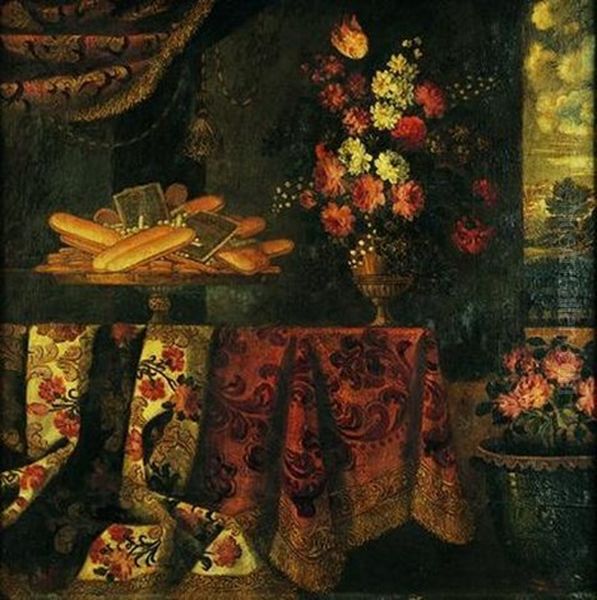

A recurring feature in Gianlisi's oeuvre is the depiction of elaborate textiles. Richly patterned carpets, often of Eastern origin, cascade over tables or entablatures, their intricate designs and vibrant colors rendered with painstaking care. Heavy draperies and curtains, sometimes pulled back to reveal the still life arrangement, add a theatrical element to his scenes, framing the composition and creating a sense of depth. These textiles are not mere accessories; they are integral components of the painting, contributing to its overall richness and tactile quality. Artists like Francesco Noletti, known as "il Maltese" (c. 1611–1654), had earlier specialized in depicting such luxurious fabrics, and Gianlisi continued this tradition with his own distinctive flair.

Fruits and flowers are also central to Gianlisi's still lifes. He depicted a wide variety of produce – grapes, peaches, figs, pomegranates, and strawberries – often shown at the peak of ripeness, their colors vivid and their forms plump. Floral arrangements, sometimes in ornate vases, add notes of delicacy and ephemeral beauty. The combination of fruits and flowers allowed Gianlisi to explore a wide chromatic range and to create compositions that were both abundant and harmonious. This focus on the bounty of nature aligns him with other Italian still life specialists such as Michelangelo Pace, called "di Campidoglio" (c. 1610 – c. 1670), known for his lush fruit and flower pieces, and the Neapolitan masters Giovan Battista Ruoppolo (1629–1693) and Giuseppe Recco (1634–1695), whose works often celebrated the fecundity of the southern Italian landscape.

The influence of the Baroque is particularly evident in the decorative quality of Gianlisi's work. His compositions are often complex and asymmetrical, with objects arranged in a seemingly casual yet carefully orchestrated manner. There is a sense of movement and dynamism, as if the scene has been captured in a fleeting moment. The play of light and shadow, or chiaroscuro, is masterfully handled, highlighting the textures of different materials and creating a sense of volume and depth. This dramatic use of light, a hallmark of Baroque painting, imbues his still lifes with a sense of vitality and presence. Cristoforo Munari (1667–1720), a contemporary active in Reggio Emilia and Florence, also produced opulent still lifes featuring musical instruments, porcelain, and rich foods, sharing with Gianlisi a taste for the luxurious and the meticulously rendered.

Representative Works: A Closer Look

Antonio Gianlisi's body of work, though perhaps not as extensively documented as some of his more famous contemporaries, includes several paintings that exemplify his style and thematic concerns. These works are primarily nature morte, showcasing his skill in arranging and depicting inanimate objects with lifelike precision and artistic flair.

One such notable piece is _Natura morta con fragole e arazzo_ (Still life with strawberries and tapestry). This painting, as its title suggests, likely features a carefully arranged composition where the vibrant red of the strawberries contrasts with the rich textures and patterns of a tapestry. The inclusion of a tapestry is characteristic of Gianlisi, allowing him to demonstrate his prowess in rendering complex woven designs and the play of light on folded fabric. The strawberries, small and delicate, would offer a focal point of intense color and a study in naturalistic detail. Such compositions often carried symbolic weight, with fruits representing abundance, transience, or even aspects of Christian iconography, though Gianlisi's primary focus seems to have been on the aesthetic and sensory qualities of the objects themselves.

Another significant work is _Natura morta con tappeto, tenda e cesto di frutta_ (Still life with carpet, curtain, and fruit basket). This larger painting (90x123 cm) would have provided Gianlisi with a more expansive canvas to develop a complex scene. The carpet, likely an oriental rug with intricate patterns, would dominate a portion of the composition, its folds and texture meticulously rendered. The curtain, perhaps partially drawn, would add a theatrical element, framing the central arrangement of a fruit basket. The basket itself, overflowing with various fruits, would be a testament to nature's bounty and Gianlisi's skill in capturing the diverse forms, colors, and textures of the produce. The interplay between the soft, yielding forms of the fruit and the structured patterns of the textiles would create a rich visual dialogue.

_Natura morta con vasi fioriti e pappagallo_ (Still life with flower vases and parrot) introduces an element of animate life into the still life arrangement. The flower vases would allow for the depiction of delicate blooms, showcasing Gianlisi's ability to capture the ephemeral beauty of flowers. The inclusion of a parrot, an exotic bird often featured in Baroque paintings for its vibrant plumage and symbolic associations (sometimes representing ostentation or, in other contexts, eloquence or even the Virgin Mary), adds a lively and colorful accent. The parrot would provide a contrast to the static nature of the other objects and would have been a popular motif, seen in the works of artists like the Flemish painter Abraham Brueghel (1631–1697), who was active in Italy.

The painting titled _Pacche, tralcio d'uva e altri frutti_ (Plates, vine shoot of grapes, and other fruits), likely a slight mistranscription of "Piatti" (plates), would focus on a more intimate arrangement. The "pacche" or plates might be simple earthenware or more elaborate porcelain, providing a reflective surface for the play of light. A trailing vine shoot of grapes, a common motif in still life, symbolizes abundance and often has Eucharistic connotations. The "altri frutti" (other fruits) would complete the composition, offering a variety of forms and colors. This work, measuring 77x64 cm, would be a concentrated study of textures and natural forms.

_Natures mortes au tapis sur un entablement_ (Still lifes with carpet on an entablature), a smaller piece (31.5x51 cm), suggests a composition where various still life elements are arranged on a stone ledge or table covered with a carpet. The entablature provides a stable horizontal element, against which the softer forms of the carpet and other objects would be set. The plural "natures mortes" (still lifes) might indicate multiple groupings within the single canvas or refer to a pair of paintings.

These works, characterized by their rich detail, vibrant colors, and sophisticated compositions, underscore Gianlisi's mastery of the still life genre. They reflect the Lombard tradition's emphasis on naturalism while embracing the decorative opulence of the Baroque. His paintings invite close inspection, revealing the artist's keen observation and his delight in the material world.

The "Gianlisi Bow": Music and Art in Cremona

A particularly intriguing work associated with Antonio Gianlisi is the large painting known as the _Gianlisi Bow_, housed in the Pinacoteca Comunale in Cremona. This piece reportedly depicts a cello and its bow with remarkable attention to detail and proportion. The city of Cremona, as the epicenter of classical violin making, provides a poignant context for such a painting. The workshops of Amati, Guarneri, and Stradivari were producing instruments that were, and still are, considered masterpieces of craftsmanship and acoustic engineering.

Gianlisi's decision to paint a cello, an instrument that was gaining prominence in the Baroque orchestra and as a solo instrument, reflects an engagement with the cultural milieu of his hometown. The meticulous rendering of the instrument, focusing on its form, the grain of the wood, the curve of the bow, and perhaps even the strings, would align with the Lombard tradition of detailed naturalism, particularly as exemplified by Evaristo Baschenis, who specialized in depicting lutes, violins, and other musical instruments.

The _Gianlisi Bow_ is more than just a still life; it can be seen as a tribute to the art of music and instrument making. In an era when the visual arts and music often intersected, with patrons commissioning works that celebrated both, such a painting would have resonated deeply. The precision required to paint the instrument accurately mirrors the precision required to craft it. Modern studies and replications of historical instruments sometimes turn to such paintings for visual information about construction details, stringing, and playing accessories of the period.

The painting's presence in Cremona's public art gallery underscores its local significance. It serves as a visual link between the city's two great artistic traditions: painting and music. For Gianlisi, depicting a musical instrument might also have offered a technical challenge, allowing him to showcase his skill in rendering complex three-dimensional forms, reflective surfaces, and the subtle interplay of light and shadow on polished wood. The work stands as a testament to his versatility within the still life genre and his connection to the unique cultural heritage of Cremona.

Artistic Identity and Scholarly Scrutiny

The artistic identity of Antonio Gianlisi, like that of many painters from earlier centuries, has been a subject of some scholarly discussion and, at times, debate. While his works are generally recognized for their quality and distinctive style, questions regarding attribution, the precise extent of his oeuvre, and his relationship to other contemporary artists have occasionally arisen. This is not uncommon for artists who were not as extensively documented by biographers like Giorgio Vasari (for Renaissance artists) or Giovanni Pietro Bellori (for some Baroque figures).

One aspect of this scrutiny involves distinguishing Gianlisi's hand from that of other painters working in a similar Lombard still life tradition. The influence of Evaristo Baschenis was pervasive, and many artists adopted his thematic concerns and stylistic approaches. Differentiating between the master, his direct pupils, and his more general followers can be challenging, often relying on subtle nuances in technique, composition, or preferred motifs. The mention of a possible connection to a "Francesco Gianlisi" suggests that Antonio may have been part of an artistic family, a common phenomenon where skills and workshop practices were passed down through generations. If Francesco Gianlisi was also a painter, distinguishing their respective works would be another layer in the art historical puzzle.

Furthermore, the attribution of unsigned works from this period can be complex. Stylistic analysis, comparison with securely attributed paintings, and sometimes technical examination (like pigment analysis or infrared reflectography, though less common for establishing initial attributions) are the tools art historians use. The "controversy" surrounding Gianlisi's artistic identity likely pertains to these ongoing processes of attribution and the refinement of his catalogue raisonné.

Despite these scholarly discussions, the core body of work attributed to Antonio Gianlisi exhibits a consistent style characterized by rich coloration, meticulous detail, a fondness for opulent textiles, and a harmonious blend of naturalism with Baroque decorative sensibilities. Researchers like Alberto Crispi have contributed to a more precise historical understanding of Gianlisi, helping to clarify his position within the Lombard school and his relationship to other artists. Such research is vital for appreciating the contributions of artists who, while perhaps not achieving the superstar status of a Caravaggio or a Bernini, were nonetheless significant contributors to the artistic fabric of their time. The continued interest in his work, as evidenced by its presence in collections and its appearance in the art market, speaks to its enduring appeal and recognized quality.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Antonio Gianlisi's active period, from 1677 to 1727, places him squarely within the vibrant and diverse art world of the late Baroque in Italy. He shared this era with a multitude of talented painters, each contributing to the rich artistic landscape. While Gianlisi specialized in still life, his contemporaries worked across various genres, reflecting the multifaceted demands of patrons and the evolving tastes of the time.

Among the figure painters active during Gianlisi's lifetime were Domenico Maria Viani (1668–1711), a Bolognese artist known for his historical and religious subjects, often characterized by a robust and dynamic style. The Bolognese school, with its strong academic tradition stemming from the Carracci, continued to be influential. Another prominent figure painter was Sebastiano Conca (1680–1764), who, though slightly younger, rose to prominence in Rome, producing elegant and highly finished works in a Rococo-tinged late Baroque style. His large-scale altarpieces and frescoes were much in demand.

In Naples, the legacy of Luca Giordano (who died in 1705) and the earlier impact of Caravaggio continued to shape painting. Artists like Francesco Solimena (1657–1747) became dominant figures, known for their dramatic compositions and rich color palettes, influencing generations of Neapolitan painters.

Within the realm of still life itself, Gianlisi was part of a flourishing tradition. As mentioned, Cristoforo Munari (1667–1720) was a significant contemporary whose opulent still lifes share thematic and stylistic affinities with Gianlisi's work. In Rome, Christian Berentz (1658–1722), a German painter active in Italy, produced sumptuous still lifes, often featuring elaborate displays of fruit, flowers, and precious objects. The tradition of flower painting, in particular, was strong, with artists like Mario Nuzzi, called Mario de' Fiori (1603–1673), having established a popular genre that continued with later specialists.

The slightly later painter Gaetano Ottani (c. 1720/24–1801), though his main activity falls after Gianlisi's death, represents the continuation of Baroque and Rococo traditions into the later 18th century, often working in Bologna and also known for theatrical designs. His work shows how stylistic trends evolved from the High Baroque period in which Gianlisi flourished.

Other notable Italian painters whose careers overlapped with Gianlisi include Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1665–1747), a Bolognese artist known for his genre scenes, religious works, and portraits, often characterized by a lively realism and expressive brushwork. In Venice, painters like Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757) were pioneering the Rococo style, particularly in pastel portraiture, while Sebastiano Ricci (1659–1734) and later Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770) were creating grand decorative schemes filled with light and airy figures.

This constellation of artists, working in different regions and genres, formed the complex artistic environment in which Antonio Gianlisi operated. His specialization in still life allowed him to carve out a distinct niche, contributing to the Lombard tradition's reputation for meticulous naturalism and decorative richness, while also engaging with the broader aesthetic currents of the Italian Baroque.

The Teacher-Student Dynamic in Baroque Art Education

While specific, detailed records of Antonio Gianlisi's own teachers or any documented students he may have formally trained are not extensively available in the provided information, understanding the general nature of artistic education during the Baroque period can offer context. The master-apprentice system was the cornerstone of artistic training in 17th and 18th-century Italy.

Young aspiring artists, often starting in their early teens, would enter the workshop (bottega) of an established master. This apprenticeship was a multifaceted experience. Initially, apprentices would perform menial tasks: grinding pigments, preparing canvases or panels, cleaning brushes, and running errands. This immersion in the practicalities of the workshop was an essential part of their learning. Gradually, they would be entrusted with more artistic responsibilities, starting with copying the master's drawings and paintings, then perhaps painting less critical parts of the master's own commissions, such as backgrounds or drapery.

The relationship between master and apprentice was often profound and could be complex. A good master would not only impart technical skills but also guide the student's artistic development, fostering their individual talents while ensuring they absorbed the workshop's style. This relationship could be akin to that of a family, with the apprentice living in the master's household. As described in general terms, an "artful" teacher-student relationship often involved deep emotional investment, mutual respect, and open dialogue. The master's role was to nurture, to challenge, and to inspire.

However, not all master-student relationships were idyllic. Some apprentices might have found the discipline harsh or the master's temperament difficult. The competitive environment of the art world could also lead to rivalries, even between a master and a particularly gifted student who might eventually surpass him. The journey from apprentice to independent master was a long one, often culminating in the student producing a "masterpiece" to be accepted into the local painters' guild, thereby gaining the right to establish their own workshop and take on commissions.

In Gianlisi's context, if he followed this typical path, he would have learned his craft through years of dedicated practice under a master, likely one well-versed in the Lombard still life tradition. He would have absorbed the techniques for rendering textures, achieving realistic effects of light and shadow, and composing balanced and engaging scenes. If he later became a master himself, he would have passed on these skills to his own apprentices, contributing to the continuity of artistic traditions. The emphasis on practical skill, combined with an understanding of composition and, depending on the genre, iconography, was paramount. This system, while varying in its individual manifestations, was fundamental to the production of art during Gianlisi's era.

Legacy and Market Presence of Antonio Gianlisi

Antonio Gianlisi's legacy primarily resides in his contribution to the Lombard school of still life painting during the High Baroque period. While he may not have achieved the widespread international fame of some of his Italian contemporaries who worked on grand-scale religious or mythological commissions, his specialized skill in the natura morta genre ensured him a respected place within that tradition. His paintings, with their meticulous detail, rich colors, and celebration of material abundance, appealed to patrons who appreciated the technical virtuosity and aesthetic pleasure such works offered.

The enduring appeal of Gianlisi's art is evident in its continued presence in private and public collections, particularly in Italy. The Pinacoteca Comunale in Cremona, for instance, holding his "Gianlisi Bow," signifies his local importance and the recognition of his contribution to the city's artistic heritage. His works also appear in the art market, with auction houses occasionally featuring his paintings. The estimated values for pieces like Natura morta con fragole e arazzo (between €10,000 and €15,000) or Pacche, tralcio d'uva ed altri frutti (between €4,000 and €5,000) indicate a consistent interest among collectors of Old Master paintings, particularly those specializing in Italian still life.

The scholarly attention given to his work, including efforts to clarify attributions and understand his place within the Lombard school, further contributes to his legacy. By studying artists like Gianlisi, art historians gain a more nuanced understanding of regional artistic developments and the diversity of talent that flourished during the Baroque era. His paintings serve as valuable documents of the material culture of the time, depicting textiles, fruits, and objects that were part of everyday life or symbols of status and taste.

Moreover, Gianlisi's dedication to naturalism, combined with a Baroque sense of opulence, created a distinctive style that continues to attract viewers. The tactile quality of his painted surfaces, the intricate rendering of patterns, and the harmonious arrangement of objects demonstrate a high level of artistic skill and a refined aesthetic sensibility. His work, like that of many still life painters, invites contemplation and appreciation for the beauty found in the ordinary and the extraordinary objects that surround us. In this sense, Antonio Gianlisi's art transcends its historical context, offering a timeless appeal through its masterful execution and visual richness.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Baroque Splendor

Antonio Gianlisi emerges from the annals of art history as a dedicated and skilled practitioner of still life painting, a genre he imbued with the characteristic naturalism of the Lombard school and the decorative splendor of the Baroque. Active in Cremona during a vibrant period of Italian art, he carved out a distinct artistic identity through his meticulous renderings of sumptuous textiles, ripe fruits, delicate flowers, and occasionally, musical instruments that paid homage to his city's renowned craftsmanship. His compositions, often complex and richly colored, demonstrate a keen eye for detail and a masterful handling of light and texture, inviting viewers into a world of tangible beauty and sensory delight.

While scholarly discussions may continue to refine the precise contours of his oeuvre and his relationships with contemporary artists, the core body of work attributed to Gianlisi speaks eloquently of his talent. His paintings, such as Natura morta con tappeto, tenda e cesto di frutta or the evocative Gianlisi Bow, stand as testaments to his ability to elevate everyday objects to subjects of profound artistic contemplation. He was part of a significant tradition of still life painting in Italy, alongside figures like Evaristo Baschenis, Cristoforo Munari, and others who explored the expressive potential of inanimate objects.

Antonio Gianlisi's legacy is preserved in the collections that house his works and in the continued appreciation of art connoisseurs and historians. He represents an important facet of the Italian Baroque, showcasing how a specialized genre like still life could achieve high levels of artistic sophistication and enduring appeal. His canvases remain a vibrant testament to the opulence, meticulousness, and artistic vitality of his era.