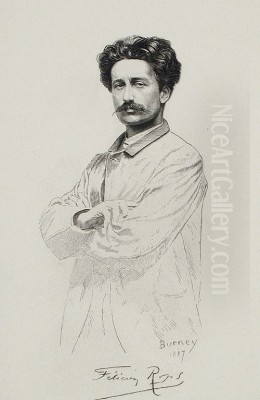

Félicien Rops stands as a pivotal yet often controversial figure in late 19th-century European art. A Belgian national, Rops navigated the complex cultural currents of his time, emerging as a leading exponent of Symbolism and the Decadent movement. Primarily celebrated for his mastery of etching and his evocative watercolors, his work delved into themes of satire, eroticism, death, and the occult, often challenging the prevailing moral and social conventions of his era. His unique vision and technical brilliance secured his place in art history, influencing contemporaries and subsequent generations, even as his subject matter courted scandal and censorship.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Namur, Belgium, on July 7, 1833, Félicien Joseph Victor Rops hailed from a comfortable middle-class background. His father, Nicholas Rops, was a successful textile manufacturer, and his mother was Sophie Maubile. His formal education began in 1844 at the local Jesuit College. Following family changes, likely the death of his father, he transferred to the Royal Athenaeum in Namur. In 1851, he enrolled at the Free University of Brussels, ostensibly to study law and philosophy. However, his true passion lay elsewhere.

Even during his university years, Rops's artistic inclinations became evident. He gravitated towards drawing and graphic arts, finding an outlet for his burgeoning talent in satirical illustration. He began contributing caricatures and lithographs to student magazines like Le Crocodile and, more significantly, to the satirical journal Uylenspiegel, which he co-founded in 1856. These early works, often sharp critiques of bourgeois society and politics, quickly garnered attention and established his reputation as a keen observer and witty commentator, laying the groundwork for his later, more complex artistic explorations. His preference for art over academia soon became definitive.

Move to Paris and Key Influences

The year 1862 marked a significant turning point in Rops's career as he sought broader horizons in Paris, the undisputed center of the European art world. There, he briefly entered the studio of the sculptor Henri-Alfred Jacquemart, refining his technical skills. More consequentially, Paris exposed him to a vibrant artistic and literary milieu. Around 1861, even before his more permanent move, he had encountered the formidable French Realist painter Gustave Courbet. Courbet's commitment to depicting contemporary life with unvarnished truthfulness and his rebellious stance against academic conventions resonated with Rops, encouraging his own tendencies towards social commentary and visual honesty.

Perhaps the most pivotal encounter during this period was his meeting with the poet Charles Baudelaire in 1864. A deep friendship and mutual artistic admiration developed between the two men. Baudelaire, whose collection Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil) explored themes of decadence, sin, and urban ennui, found a kindred spirit in Rops. This relationship profoundly shaped Rops's artistic direction, steering him further towards Symbolism and the exploration of darker psychological and spiritual landscapes. His association with Baudelaire cemented his place within the avant-garde circles of Paris.

Rops also cultivated relationships with other prominent figures in the Parisian art scene. He became close friends with the French etcher Félix Bracquemond, a key figure in the revival of etching as a fine art form. Their shared interest in printmaking techniques likely fostered technical exchanges and mutual support. Rops moved fluidly between Brussels and Paris throughout much of his career, maintaining connections in both cities, but his experiences and relationships in Paris were crucial in forging his mature artistic identity. He also interacted with writers like Stéphane Mallarmé, further embedding him within the Symbolist movement.

Thematic Concerns: Satire, Eros, and the Macabre

Félicien Rops's oeuvre is characterized by a recurring set of potent and often unsettling themes. Building on his early work as a caricaturist, social satire remained a constant thread. He relentlessly targeted the hypocrisy and moral failings he perceived in bourgeois society, the clergy, and political institutions. His critiques were often biting, employing exaggeration and grotesque imagery to expose societal decay and pretense. Works like Un Enterrement au pays wallon (A Burial in Walloon Country, 1863) exemplify this satirical edge, mocking the performative solemnity of funeral rites.

Parallel to satire, Rops delved deeply into the realms of eroticism and sexuality. His depictions often transgressed the boundaries of contemporary propriety, exploring desire, seduction, and the power dynamics between sexes with an explicitness that shocked many. He became particularly known for his portrayal of the femme fatale – alluring, dangerous women who embodied both temptation and destruction. These figures, often rendered with sharp, knowing gazes, challenged traditional notions of femininity and reflected late 19th-century anxieties about female emancipation and sexuality.

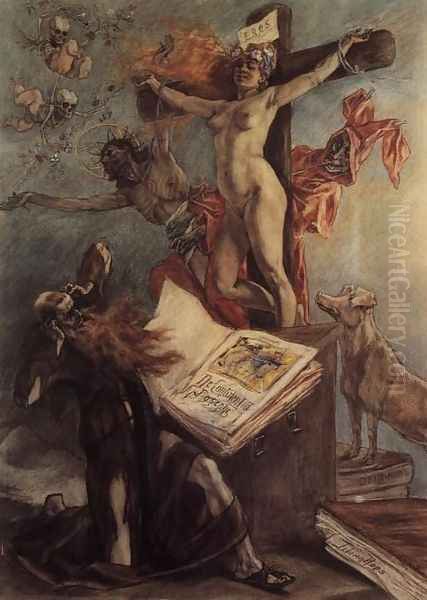

The macabre and the occult also held a powerful fascination for Rops. Death, decay, and Satanism frequently appear in his work, often intertwined with erotic themes. He explored the darker aspects of human nature and spirituality, drawing inspiration from literature, mythology, and contemporary occultism. Series like Les Sataniques and illustrations for works like Barbey d'Aurevilly's Les Diaboliques showcase his engagement with demonic imagery and the allure of transgression. These provocative themes, rendered with technical brilliance, cemented Rops's reputation as an artist who dared to confront the forbidden and the taboo, making him a central figure in the Decadent movement. His work resonated with the fin-de-siècle mood of disillusionment and morbid introspection.

Mastery of Printmaking

While Rops worked proficiently in watercolor and occasionally oil painting, his most significant contribution lies in the field of printmaking, particularly etching. He possessed an exceptional command of various etching techniques and played a crucial role in their revival and innovation during the latter half of the 19th century. He was especially adept at drypoint, a technique where the image is scratched directly onto the copper plate with a sharp needle, producing rich, velvety lines but allowing for only a small number of high-quality impressions.

Rops is also credited with helping to revive and popularize soft-ground etching (vernis mou). This technique involves drawing on a piece of paper laid over a plate coated with a soft, waxy ground. When the paper is lifted, the ground adheres to the drawn lines, exposing the metal beneath for etching. The resulting lines mimic the texture of pencil or crayon drawings, allowing for greater tonal subtlety and a softer effect than traditional hard-ground etching. Rops masterfully employed this technique to achieve nuanced atmospheric effects and delicate modeling in his prints.

His technical virtuosity was not merely an end in itself but served his expressive aims. The intricate lines of etching allowed him to render complex details and convey psychological intensity, while the tonal possibilities of techniques like soft-ground etching and aquatint enhanced the moody, often somber atmosphere of his works. Recognizing the importance of etching as an original art form, Rops was instrumental in founding the Société Internationale des Aquafortistes (International Society of Etchers) in Brussels in 1869, promoting the medium and fostering collaboration among printmakers. His dedication to the craft earned him the admiration of fellow artists like Edgar Degas and later, Edvard Munch, who recognized his technical prowess.

Major Works and Illustrations

Félicien Rops's legacy is anchored by several iconic works and influential illustration projects that encapsulate his thematic concerns and technical skill. One of his most famous and controversial images is Pornocrates, also known as La Dame au cochon (The Lady with the Pig), created around 1878. This striking composition depicts a blindfolded, semi-nude woman being led by a pig on a leash, walking atop a frieze representing the arts. It serves as a powerful allegory of human baseness triumphing over higher aspirations, a quintessential statement of Decadent disillusionment.

His close relationship with Charles Baudelaire resulted in significant illustrative work. In 1866, Rops created the frontispiece for Les Épaves (The Wreckage), a collection of poems banned from the second edition of Les Fleurs du mal. The image, featuring a skeletal tree bearing the seven deadly sins as fruit beneath symbols of death and decay, perfectly captured the morbid essence of Baudelaire's poetry and became an emblem of their shared artistic vision.

Rops frequently tackled religious themes, often subversively. The Temptation of St. Anthony (c. 1878) reimagines the biblical story as a confrontation with overt female sexuality, replacing the traditional monstrous demons with a seductive vision of Christ on the cross transformed into a voluptuous nude woman. This provocative blend of the sacred and profane is characteristic of Rops's challenging approach to established iconography. His series Les Sataniques (c. 1882) further explored themes of demonic influence, sin, and spiritual corruption through haunting and often disturbing imagery.

He also provided illustrations for Joris-Karl Huysmans and Joséphin Péladan, key figures of the Decadent and Symbolist literary movements. His illustrations for Barbey d'Aurevilly's Les Diaboliques (1882) visualized the book's tales of passion and perversity, while his collaboration with Charles De Coster on Légendes flamandes (Flemish Legends) showcased his ability to engage with folklore and national identity, albeit through his characteristic dark lens. Early satirical works like Un Enterrement au pays wallon (1863) and various caricatures, such as those potentially titled Mr. Corentin's Administrators, established his critical voice early on. Works like Les Dames au Pantin (Ladies with a Puppet) continued his exploration of female power and manipulation, while Sirène à l'affût (Siren on the Lookout, 1884) demonstrated his capacity for poetic, mythological imagery.

Symbolism and the Decadent Movement

Félicien Rops is inextricably linked with the Symbolist and Decadent movements that flourished in Europe, particularly in France and Belgium, during the late 19th century. These movements emerged as a reaction against Naturalism and Realism, prioritizing subjectivity, emotion, and the exploration of inner worlds over objective representation. Symbolism sought to evoke ideas and feelings through suggestive imagery, often drawing on mythology, dreams, and the spiritual realm. Artists like Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon were key French proponents.

Decadence, often seen as a darker, more self-conscious offshoot of Symbolism, embraced themes of artificiality, perversity, morbidity, and societal decline. It reflected a sense of weariness and disillusionment with modern progress and bourgeois values. Rops's work perfectly embodies many tenets of both movements. His focus on suggestion rather than explicit narration, his fascination with the mystical and the occult, and his exploration of complex psychological states align him firmly with Symbolism.

His preoccupation with sin, eroticism, death, Satanism, and the critique of societal decay places him at the heart of the Decadent sensibility. His art often visualizes the anxieties and obsessions articulated by Decadent writers like Baudelaire, Huysmans (whose novel À rebours became a key text of the movement and praised Rops), and Péladan. Rops's femme fatale figures, his depictions of urban vice (as seen in works like Bouge à Matelots), and his general atmosphere of morbid sensuality became defining motifs of the era's artistic output. He, alongside fellow Belgian artists like James Ensor, contributed significantly to the distinct character of Belgian Symbolism.

Personal Life and Controversies

Rops's personal life was as unconventional and fraught with controversy as his art. In 1857, he married Charlotte Polet de Faveaux, the daughter of a judge from Namur. The couple had two children, Paul and Juliette. However, the marriage gradually deteriorated, reportedly strained by financial difficulties and perhaps Rops's restless nature and artistic pursuits. They eventually separated, and the marriage formally ended around 1875.

Following the breakdown of his marriage, Rops entered into a long-term relationship with two sisters, Léontine and Aurélie Duluc. The Duluc sisters ran a successful fashion boutique in Paris, specializing in women's shoes. Rops lived with them in what was essentially a ménage à trois, a domestic arrangement that defied conventional morality and attracted considerable social disapproval. He had a daughter, Claire, with Léontine in 1871, who later married the Belgian writer Eugène Demolder. This unconventional lifestyle further cemented Rops's image as a bohemian figure operating outside bourgeois norms.

His health was also a source of concern, particularly in his later years. He reportedly suffered from several ailments, including diabetes, hypertension, and heart problems, possibly exacerbated by his lifestyle. Despite these challenges, he continued to work prolifically. His death on August 23, 1898, at his home, La Demi-Lune, in Essonnes (now Corbeil-Essonnes) near Paris, occurred after a period of prolonged suffering during an intense summer heatwave. Anecdotal accounts describe his passing dramatically, contributing to the legendary aura surrounding his life and work. He was 65 years old.

Interactions with Contemporary Artists

Throughout his career, Félicien Rops engaged with a wide circle of artists and writers, both influencing and being influenced by the creative currents of his time. His early connection with Gustave Courbet provided a grounding in Realist principles, emphasizing direct observation and a rejection of academicism, even as Rops moved towards more subjective and imaginative themes. His friendship with Charles Baudelaire was arguably the most transformative, aligning his artistic vision with the nascent Symbolist and Decadent literary movements.

In Paris, his friendship with the etcher Félix Bracquemond was significant, placing him within a network of printmaking revivalists that also included figures like Édouard Manet, who was also experimenting boldly with the medium. Rops's technical mastery, particularly in etching, earned him respect among his peers. Edgar Degas, known for his own innovative printmaking and depictions of modern Parisian life (including dancers and brothel scenes), admired Rops's skill.

Rops's work resonated strongly with younger artists exploring similar themes of psychological depth and societal critique. The Norwegian painter Edvard Munch, whose work delves into anxiety, death, and sexuality, acknowledged Rops's influence. Comparisons can also be drawn between Rops's satirical bite and that of earlier masters like the Spanish artist Francisco Goya or the French caricaturist Honoré Daumier, though Rops's focus was distinctly fin-de-siècle. Within Belgium, his contemporary James Ensor shared a penchant for the grotesque and satirical social commentary. While perhaps stylistically different, the mention of similarities to Frans Hals or Auguste Renoir in some accounts points to a broad awareness of art history, though Rops's core affinities lay firmly within the Symbolist and Decadent circles alongside artists like Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon.

Social Impact and Critical Reception

Félicien Rops's art inevitably provoked strong reactions from the society he depicted and critiqued. His willingness to tackle taboo subjects like explicit sexuality, religious subversion, and death with unflinching, often satirical, honesty ensured that his work was frequently at the center of controversy. In an era largely defined by Victorian and bourgeois codes of morality and propriety, Rops's art was seen by many as scandalous, obscene, and deeply immoral.

His illustrations for Baudelaire's Les Épaves faced censorship issues, mirroring the legal troubles that plagued Les Fleurs du mal. His submissions to official exhibitions, like the Paris Salon, could also ignite debate. The exhibition of certain works in the 1884 Salon, for instance, reportedly caused significant outcry due to their perceived indecency. This notoriety, however, also served to enhance his reputation among the avant-garde, who saw his defiance of convention as a mark of artistic integrity and courage.

While conservative critics and the general public often condemned his work, Rops garnered significant admiration from fellow artists and writers within the Symbolist and Decadent circles. Figures like Joris-Karl Huysmans lauded his ability to capture the complex, often perverse, spirit of the age. His art was seen as a necessary antidote to the perceived hypocrisy and superficiality of mainstream culture. He exposed the underbelly of modern society, forcing viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about human nature, desire, and mortality. His impact lay in this very challenge to complacency, pushing the boundaries of acceptable artistic expression.

Later Years and Legacy

In his later years, Félicien Rops spent more time at his property, La Demi-Lune, in Essonnes, south of Paris. While he continued to create art, he also devoted considerable energy to his passion for botany and gardening. This retreat into nature offered a counterpoint to the often dark and intense themes of his artistic output. He cultivated rare plants and corresponded with botanists, finding solace and intellectual stimulation in the natural world.

Despite this quieter phase, his artistic reputation endured. He remained a respected, if still controversial, figure in European art circles. His death in 1898 marked the passing of a unique artistic voice that had profoundly shaped the visual culture of the late 19th century.

Félicien Rops's legacy is multifaceted. As a printmaker, he was a technical innovator who contributed significantly to the etching revival, mastering techniques like drypoint and soft-ground etching to achieve remarkable expressive effects. Thematically, he stands as a crucial figure in Symbolism and Decadence, giving visual form to the movements' preoccupations with subjectivity, eroticism, death, and social critique. His unflinching exploration of controversial subjects challenged societal norms and expanded the boundaries of artistic representation.

Though sometimes overshadowed by French contemporaries, Rops's influence was significant, impacting artists like Edvard Munch and contributing to the broader development of modern art's engagement with psychological depth and social commentary. Today, his work is preserved in major museum collections worldwide, and the Musée Félicien Rops in his hometown of Namur is dedicated to preserving and promoting his complex and enduring artistic heritage. He remains a compelling figure, whose art continues to fascinate and provoke through its technical brilliance and daring exploration of the human condition.