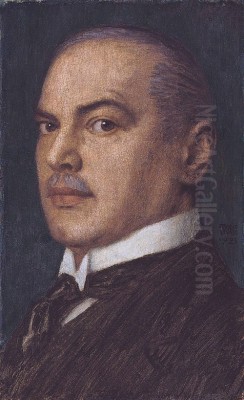

Franz von Stuck stands as a towering figure in German art at the turn of the 20th century. A painter, sculptor, printmaker, and architect, he navigated the complex currents of fin-de-siècle culture, becoming a leading proponent of Symbolism and a co-founder of the influential Munich Secession. Born in Tettenweis, Lower Bavaria, in 1863, Stuck rose from humble beginnings to become a celebrated artist and respected professor, leaving an indelible mark on the artistic landscape of Munich and beyond. His work, characterized by its engagement with mythology, its bold sensuality, and its unique blend of darkness and humor, continues to fascinate and provoke discussion.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Franz Stuck's journey into the art world began not with grand canvases, but with drawings and illustrations. Born into a rural miller's family, his early talent for drawing was evident. He pursued formal art education, initially at the Royal School of Arts and Crafts (Königliche Kunstgewerbeschule) in Munich. During these formative years, he honed his skills, particularly in draughtsmanship, contributing humorous illustrations and vignettes to publications like the Viennese magazine Allegorien und Embleme, published by Gerlach & Schenk, which showcased his early wit and decorative flair.

His ambition soon led him to the prestigious Munich Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der Bildenden Künste München) around 1881-1885. Though records of his formal enrollment duration vary, his time absorbing the academic atmosphere was crucial. He studied under notable artists, potentially including Ferdinand Barth, and was exposed to the prevailing historical and mythological painting traditions. However, Stuck was already developing a distinctive voice, one that looked beyond academic convention towards more personal and psychologically charged interpretations of classical and allegorical themes. His early graphic work already hinted at the thematic preoccupations – mythology, allegory, sensuality – that would define his mature career.

The Munich Secession: A Break with Tradition

The late 19th century saw growing dissatisfaction among progressive artists with the conservative exhibition policies of the established art institutions. In Munich, the official Künstlergenossenschaft (Artists' Association) dominated the exhibition scene, often favoring traditional, academic styles. Franz von Stuck, alongside other forward-thinking artists like Wilhelm Trübner and Fritz von Uhde, became a central figure in the movement seeking change.

In 1892, this dissatisfaction culminated in the formation of the Munich Secession. Stuck was not merely a member; he was a driving force and co-founder. The Secession aimed to break free from the perceived stagnation of the official art world, championing artistic freedom, individualism, and higher standards of quality in exhibitions. They sought to promote modern art movements, including Symbolism, Impressionism (though less central in Munich than elsewhere), and the burgeoning Jugendstil (Art Nouveau). The Secession's exhibitions provided a vital platform for artists exploring new styles and themes, challenging the public and critics alike. Stuck's involvement cemented his position as a leader of the avant-garde in Munich.

Symbolism and Signature Themes

Franz von Stuck's name is virtually synonymous with German Symbolism. Moving away from the naturalism or historical realism favored by the academy, Symbolist artists sought to express ideas, emotions, and psychological states through suggestive imagery, metaphor, and myth. Stuck excelled in this realm, drawing heavily on classical mythology, biblical narratives, and allegorical concepts, but infusing them with a distinctly modern sensibility, often charged with eroticism and psychological tension.

His subjects frequently included figures like sphinxes, centaurs, fauns, sirens, and biblical characters such as Salome or Judith. However, he reinterpreted these familiar figures, focusing on their primal, often dangerous, or seductive aspects. His paintings are characterized by strong contrasts of light and shadow, rich, often dark color palettes, and meticulously rendered surfaces. He often designed elaborate frames for his paintings, considering them integral parts of the total artwork, enhancing their symbolic meaning and decorative impact. This approach reflected the Symbolist interest in creating immersive, evocative experiences.

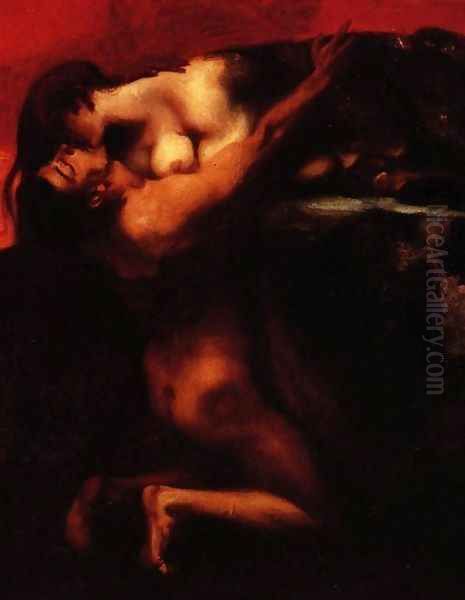

Die Sünde (The Sin): An Iconic Masterpiece

Perhaps no single work better encapsulates Franz von Stuck's artistic concerns and public impact than Die Sünde (The Sin). First exhibited in 1893 at the inaugural Munich Secession exhibition, the painting caused an immediate sensation and became one of the most famous images of the era. Stuck created multiple versions of this subject between 1891 and 1912.

The painting typically depicts a large, pale female nude standing in near darkness, her body entwined by a massive, dark serpent whose head rests near her shoulder, its gaze often directed towards the viewer. The woman's own expression is ambiguous – sometimes interpreted as seductive, sometimes trance-like, sometimes aware of her transgression. The stark contrast between the luminous flesh and the enveloping darkness, the intimate yet menacing presence of the snake (symbolizing temptation, knowledge, primal forces), and the direct, challenging gaze created a powerful and unsettling image. It tackled themes of guilt, sexuality, and the nature of temptation head-on, resonating with the fin-de-siècle fascination with psychology and the darker aspects of human nature. The work won a gold medal at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, catapulting Stuck to international fame.

The Femme Fatale and Depictions of Gender

A recurring motif in Stuck's oeuvre is the powerful, often dangerous female figure – the femme fatale. Works like Salome (depicting the biblical princess often associated with deadly seduction), Judith (the biblical heroine who beheaded Holofernes), The Sphinx, and various portrayals of sirens or mythological temptresses explore themes of female power, allure, and potential destructiveness. This fascination was shared by many Symbolist and Art Nouveau artists across Europe, including Gustave Moreau in France and Gustav Klimt in Austria.

Stuck's femmes fatales are rarely passive victims; they often possess an unnerving self-awareness and control. His Wounded Amazon (1903), while depicting vulnerability, still presents a strong, classical female form, challenging traditional representations. These depictions, however, were not without controversy. Critics then and now have debated whether Stuck's work celebrated female power or merely reflected and reinforced contemporary male anxieties about female emancipation, objectifying women as symbols of primal, uncontrollable forces. Regardless of interpretation, his complex and often provocative portrayal of women remains a significant aspect of his legacy.

Masterpieces and Stylistic Range

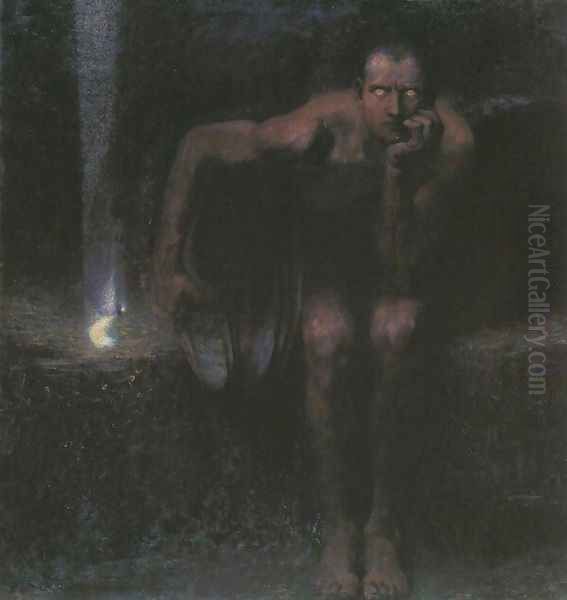

Beyond Die Sünde, Stuck produced a rich body of work exploring various facets of his symbolic world. His painting War (1894) is a terrifying allegory, personified by a relentless, armor-clad figure on horseback trampling over corpses under a blood-red sky. It captures a sense of primal violence and impending doom that resonated deeply in the pre-World War I era. Lucifer (c. 1890) presents a brooding, seated figure, embodying fallen pride and intellectual darkness, showcasing Stuck's ability to convey complex psychological states through posture and chiaroscuro.

His stylistic range extended from these dark, monumental canvases to lighter, more decorative works. He continued to produce graphic art and designs throughout his career. While Symbolism remained central, his later works sometimes showed a renewed engagement with classical forms, albeit always filtered through his unique lens. His technical mastery, particularly his handling of oil paint to achieve smooth, enamel-like surfaces or dramatic textures, was widely admired. He often employed stark compositions and bold lighting to heighten the emotional and symbolic impact of his subjects.

The Gesamtkunstwerk: Villa Stuck

Franz von Stuck's artistic ambitions extended beyond the canvas and pedestal. He envisioned art as encompassing all aspects of life, a concept embodied in the German ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). Between 1897 and 1898, he designed and built his own residence and studio on Prinzregentenstrasse in Munich, known as the Villa Stuck. A later studio wing was added between 1913 and 1914.

The Villa Stuck is a remarkable testament to his vision. He meticulously designed every detail, from the neoclassical-inspired facade and overall architectural plan to the interior decoration, furniture, lighting fixtures, and even the garden layout. The interiors blend classical motifs (mosaics, sculptures, Pompeian colors) with Jugendstil elements and Stuck's own symbolic iconography. The villa served not only as his home and workplace but also as a carefully curated environment showcasing his artistic philosophy and personal taste. It was a stage for his life and art, embodying the integration of art and life. The design earned him another gold medal, this time for interior design, at the 1900 Paris World's Fair. Today, the Villa Stuck functions as a museum, preserving his legacy and hosting exhibitions of modern and contemporary art.

Stuck as Educator: Shaping the Next Generation

In 1895, Stuck's prominence earned him a professorship at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, the very institution whose conservatism he had challenged through the Secession. Despite this seeming contradiction, he became an influential teacher, attracting students who would themselves become pioneers of 20th-century art. His teaching methods were reportedly less rigid than traditional academic approaches, perhaps encouraging a degree of individual expression.

His most famous students include Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee, both key figures in the development of abstract art and associated with the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter) group, which also formed in Munich. Other notable students included Josef Albers, later a crucial figure at the Bauhaus and Black Mountain College; the German painters Hans Purrmann and Albert Weisgerber; and the Czech painter Georges Kars. While these artists ultimately pursued vastly different artistic paths, their early exposure to Stuck's technical skill, his engagement with color and form, and the vibrant artistic atmosphere he fostered undoubtedly played a role in their development. His position at the Academy allowed him to influence a generation grappling with the transition towards Modernism.

Contemporaries: Influence and Dialogue

Franz von Stuck did not create in isolation. He was part of a dynamic European art scene, interacting with, influencing, and being influenced by numerous contemporaries. His work shows affinities with other major Symbolists. The Swiss painter Arnold Böcklin, known for works like Isle of the Dead, was an important precursor whose mythological landscapes and symbolic intensity clearly impacted Stuck. The French Symbolist Gustave Moreau shared Stuck's interest in exoticism and complex mythological narratives. The Belgian artist Félicien Rops explored similarly dark and erotic themes.

Within the German-speaking world, Max Klinger was another multi-talented artist (painter, sculptor, printmaker) exploring Symbolist themes with psychological depth. Stuck's role in the Munich Secession placed him in dialogue with artists like Lovis Corinth and Max Slevogt, who navigated between Impressionism and Expressionism. His relationship with Gustav Klimt, the leader of the Vienna Secession, was particularly significant. Both were central figures in their respective Secession movements, shared an interest in Symbolism, decorative surfaces, and the femme fatale motif, and were key proponents of the Art Nouveau style (Jugendstil). While potentially rivals, they represented parallel developments in Munich and Vienna. The linear elegance and sometimes decadent quality of the English artist Aubrey Beardsley's work also resonates with the broader Art Nouveau context in which Stuck operated. Furthermore, the psychological intensity in some of Stuck's work finds echoes in the art of Edvard Munch.

Controversies and Critical Reception

Stuck's career was marked by both immense success and significant controversy. His bold embrace of erotic themes, particularly in works like Die Sünde, challenged the moral sensibilities of the late Wilhelmine era, leading to heated public debate even as it brought him fame. His depictions of women, as noted, drew criticism for perceived objectification or reinforcement of negative stereotypes, a debate that continues in contemporary assessments.

The founding of the Munich Secession was itself a controversial act, a direct challenge to the established artistic order. While it invigorated the Munich art scene, it also created divisions. Even his architectural masterpiece, the Villa Stuck, faced criticism later in his life, with some finding its elaborate design overly theatrical or impractical compared to the emerging functionalism of modern architecture.

His reputation fluctuated over time. He was highly celebrated, even ennobled (adding "von" to his name) in 1906, becoming a veritable "prince of painters" in Munich society. However, with the rise of Expressionism, Cubism, and abstraction in the early 20th century, Stuck's Symbolist style began to seem retrospective to the avant-garde. After his death in 1928, his work was somewhat overshadowed by subsequent modernist movements and was later complicated by the Nazi regime's ambiguous relationship with 19th-century German art. It was only in the later 20th and early 21st centuries that his work received renewed critical attention, recognizing his crucial role in the transition from academicism to modern art and his unique contribution to Symbolism and Jugendstil.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Franz von Stuck's legacy is multifaceted. As a painter and sculptor, he created some of the most iconic images of the Symbolist movement, works that continue to resonate with their blend of classical mythology, psychological depth, and sensual allure. His technical skill and innovative compositions solidified his place as a major figure in German art history.

As an architect and designer, his Villa Stuck remains a unique example of the Gesamtkunstwerk ideal, a testament to his holistic artistic vision. It stands as a significant monument in Munich, preserving his environment and serving as a center for art.

As an educator, he played a pivotal role in the training of artists like Kandinsky, Klee, and Albers, who would go on to redefine modern art. While their mature styles diverged radically from his own, his influence as a teacher and figurehead in the dynamic Munich art scene was undeniable.

Franz von Stuck bridged the 19th and 20th centuries, embodying the complexities and contradictions of the fin-de-siècle. He championed modern art through the Secession while remaining deeply engaged with classical tradition. His exploration of myth, psychology, and sensuality captured the spirit of his age and left a lasting imprint on the development of European art. His work continues to be exhibited, studied, and appreciated for its technical brilliance, thematic richness, and enduring power.