Henry François Farny stands as a significant figure in American art history, an artist whose life and work bridged continents and cultures. Born in France but raised in the United States, Farny dedicated much of his career to depicting the lives of Native American peoples during a period of profound and often tragic transformation in the American West. His meticulously rendered paintings and illustrations offer a perspective distinct from many of his contemporaries, characterized by careful observation, technical proficiency honed in Europe, and a deep-seated empathy for his subjects. Farny was not merely a painter of the "Wild West"; he was a chronicler of cultures, an observer of humanity, and an artist whose work continues to resonate for its historical insight and artistic merit.

From Alsace to the American Frontier: Early Life and Influences

Henry Farny's journey began in Ribeauvillé, Alsace, France, on July 15, 1847. His family, led by his father Charles Farny, were supporters of the French democratic movements that culminated in the revolutions of 1848. Following the suppression of these movements and the rise of Napoleon III, the Farny family, like many other political refugees (often referred to as "Forty-Eighters"), sought refuge and opportunity elsewhere. In 1853, they emigrated to the United States, settling near the town of Warren in northwestern Pennsylvania.

This relocation proved profoundly influential for the young Henry. The area around Warren was near Seneca Nation territory, and the Farny family's proximity led to significant interaction between Henry and the local Seneca people. Unlike many settlers who viewed Native Americans with suspicion or hostility, Farny developed genuine friendships. He learned from them, observing their skills in hunting and woodcraft, listening to their stories, and gaining an appreciation for their way of life. This early, formative exposure instilled in him a lifelong fascination and respect for Native American cultures, a perspective that would fundamentally shape his artistic vision.

In 1859, the Farny family moved again, this time to Cincinnati, Ohio. Cincinnati was rapidly becoming a major urban center in the American Midwest, a hub of commerce, industry, and burgeoning cultural activity. It was here that Farny's artistic inclinations began to find practical application. The city offered opportunities that the more rural environment of Pennsylvania could not, setting the stage for his formal entry into the world of art and illustration.

Artistic Training: Cincinnati and Europe

Cincinnati provided the environment for Farny's initial artistic training. He began his career not as a painter, but as an apprentice lithographer. Lithography was a crucial medium for commercial printing and illustration in the mid-19th century, and this apprenticeship provided Farny with valuable skills in drawing, composition, and the technical aspects of print production. This practical grounding would serve him well throughout his career, particularly in his later work as an illustrator.

During the 1860s, Farny's talent gained recognition, leading him to work as an illustrator for prominent national publications. He briefly contributed to Harper's Weekly, one of the most widely circulated magazines of the era, known for its high-quality illustrations depicting current events and American life. This early professional experience exposed him to the demands of narrative illustration and connected him with the broader artistic currents of the time.

Seeking more advanced training, Farny, like many ambitious American artists of his generation, looked to Europe. Around 1867, he traveled to Germany and enrolled at the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Düsseldorf. The Düsseldorf Academy was renowned for its emphasis on meticulous realism, detailed draftsmanship, and narrative clarity. There, Farny studied under artists such as Hermann Hartzog (sometimes cited as Hartmann) and Thomas Read. The Düsseldorf School's rigorous approach profoundly influenced Farny's technique, reinforcing his inclination towards careful observation and detailed rendering.

While in Europe, Farny also likely absorbed other influences, potentially traveling to Munich or Paris, though his primary training ground was Düsseldorf. Upon returning to the United States around 1870, he brought back a sophisticated European technique combined with his uniquely American experiences, particularly his foundational interest in Native American life. Some accounts suggest he also studied or associated closely with fellow Cincinnati artists Frank Duveneck and John Henry Twachtman around this period, likely after his return from Europe. These connections placed him within a dynamic circle of American artists grappling with European traditions and forging new paths in American art.

Return to Cincinnati and a Flourishing Illustration Career

Upon his return from Europe around 1870, Farny settled back in Cincinnati, which would remain his primary base for the rest of his life. He quickly established himself as a highly sought-after illustrator. His European training, combined with his innate talent and understanding of American themes, made his work appealing to publishers. He resumed his relationship with Harper's Weekly and also began contributing illustrations to other major periodicals, most notably The Century Magazine.

His work extended beyond magazines. Farny created illustrations for books, including the famous McGuffey's Eclectic Readers, educational primers that shaped the values and literacy of generations of American schoolchildren. His illustrations for these readers often depicted scenes of American life, history, and nature, requiring clarity and accessibility. He also undertook commercial work, designing advertisements and even circus posters, demonstrating his versatility and the practical application of his artistic skills. He produced illustrations for the publishing firm Van Antwerp, Bragg & Co. (later part of the American Book Company), further solidifying his role in the visual culture of the time.

While illustration provided a steady income and kept his work visible to a wide audience, Farny harbored ambitions as a painter. His illustration work often touched upon the themes that would dominate his paintings, including depictions of frontier life and Native Americans. This period allowed him to refine his compositional skills and narrative abilities, laying the groundwork for his transition towards focusing more intently on easel painting, particularly his evocative portrayals of the American West and its original inhabitants.

The Call of the West: Travels and Encounters

Despite his success as an illustrator based in Cincinnati, Farny felt the pull of the American West, the source of his deepest artistic inspiration. He recognized that authentic portrayal required firsthand experience. In 1881, he embarked on his first major journey west, traveling up the Missouri River to Fort Yates in the Dakota Territory. This was Sioux territory, and the trip provided him with invaluable opportunities to observe the landscape, meet the people, and gather sketches and artifacts.

This initial trip was pivotal. It coincided with a commission from The Century Magazine to illustrate an article about the surrender of the prominent Sioux leader, Chief Gall. Farny's presence on the scene allowed him to create accurate and compelling images related to this significant event, further enhancing his reputation. This journey solidified his commitment to depicting Native American life based on direct observation rather than relying on stereotypes or secondary sources.

Over the next decade and a half, Farny made several more trips west. He traveled to Montana, documenting the Crow people and observing the changes brought by the expansion of the Northern Pacific Railroad, another subject he covered for The Century. He journeyed to the Southwest, encountering Zuni and Apache communities, broadening his understanding of the diverse cultures across different regions. These expeditions were not casual tours; they were working trips where Farny immersed himself, sketching, taking photographs (a relatively new tool he utilized for reference), and collecting cultural objects – clothing, tools, weapons – which he would later use as props in his Cincinnati studio to ensure accuracy in his paintings.

One particularly notable encounter occurred in 1884 when Farny met the legendary Hunkpapa Lakota leader Sitting Bull. Although Sitting Bull was effectively a prisoner of the U.S. military at the time, Farny managed to spend time observing him and gathering impressions. While Sitting Bull reportedly refused to pose formally for many artists, Farny's respectful approach and genuine interest likely facilitated this interaction. These travels provided the raw material – the visual data, the cultural understanding, the atmospheric sense of place – that fueled his major paintings for years to come. His final documented trip west occurred in 1894.

Subject Matter: Depicting Native American Life with Dignity

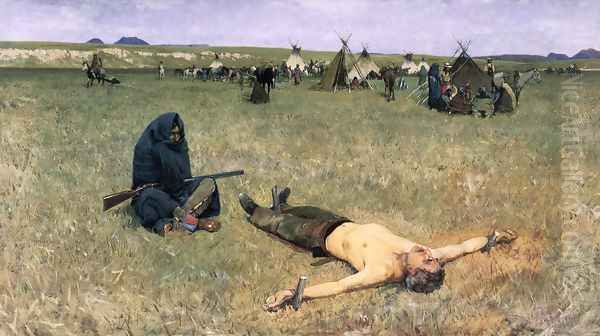

Henry Farny's primary subject was the Native American. Unlike many artists who focused on dramatic scenes of conflict or romanticized stereotypes of the "noble savage," Farny concentrated on portraying the daily lives, dignity, and resilience of his subjects. His paintings often depict quiet, contemplative moments: hunters tracking game, families setting up camp, individuals traveling through vast landscapes, or small groups in council.

He painted various tribes he encountered during his travels, including the Sioux (Lakota), Crow, Apache, Zuni, Comanche, and Blackfeet, as well as drawing upon his childhood memories of the Seneca. His works often emphasize the harmony between people and the natural environment. Landscapes are not mere backdrops but integral parts of the scene, shaping the lives of the inhabitants. He rendered the specific details of clothing, dwellings (tipis, pueblos), and accoutrements with ethnographic care, informed by the sketches, photographs, and artifacts he collected.

While aware of the tragic circumstances facing Native Americans – the loss of land, the destruction of the buffalo herds, confinement to reservations – Farny rarely depicted overt violence or despair. Instead, his work often carries a sense of melancholy, a quiet acknowledgment of a changing world. He captured the pride and endurance of individuals navigating these transitions. His sympathetic viewpoint is evident in the respectful and individualized portrayal of figures, avoiding the generic representations common at the time. He aimed to present Native Americans as complex human beings, grounded in their cultures and environments. This focus on peaceful, everyday scenes, rendered with sensitivity, distinguishes his work from the more sensationalist Western art of some contemporaries.

Artistic Style and Technique

Farny's artistic style was deeply rooted in the realism he absorbed at the Düsseldorf Academy. His work is characterized by meticulous draftsmanship, careful attention to detail, and a smooth, refined finish. He possessed a strong ability to render textures accurately, whether it be the hide of a tipi, the fur of an animal, the fabric of clothing, or the specific geology of the Western landscape. This precision gives his work a sense of authenticity and immediacy.

He worked proficiently in several media, including oil painting, watercolor, and gouache (an opaque watercolor). Gouache became a favored medium, particularly for his finished paintings. Its opacity allowed for precise detail and rich color, well-suited to his realistic style. His compositions are typically well-structured and balanced, often featuring strong horizontal lines that emphasize the vastness of the plains or the layered horizons of the badlands. Figures are carefully integrated into the landscape, reinforcing the connection between the people and their environment.

Farny’s use of light is notable. He generally preferred clear, natural light, often depicting scenes in the bright sun of midday or the softer tones of dawn or dusk. He avoided the dramatic, almost theatrical chiaroscuro favored by some Romantic painters, opting instead for a more even illumination that enhances the clarity and detail of the scene. His color palette could range from the subtle, earthy tones of the plains and badlands to richer hues in depictions of clothing or ceremonial objects. Some critics have noted a potential influence from Japanese prints in certain compositional choices, such as flattened perspectives or asymmetrical arrangements, though the core of his style remained grounded in Western realism. This blend of European technique and American subject matter, filtered through his personal sensibility, resulted in a unique and recognizable style.

Key Works and Masterpieces

Several works stand out in Henry Farny's oeuvre, showcasing his technical skill and thematic concerns. In the Badlands (c. 1905) is often considered one of his masterpieces. This painting exemplifies his ability to capture the unique atmosphere and geology of the Western landscape, using a subtle palette of greens, blues, and ochres. The composition, with its strong horizontal bands and carefully placed figures on horseback, conveys a sense of quietude and vast space, characteristic of his mature style.

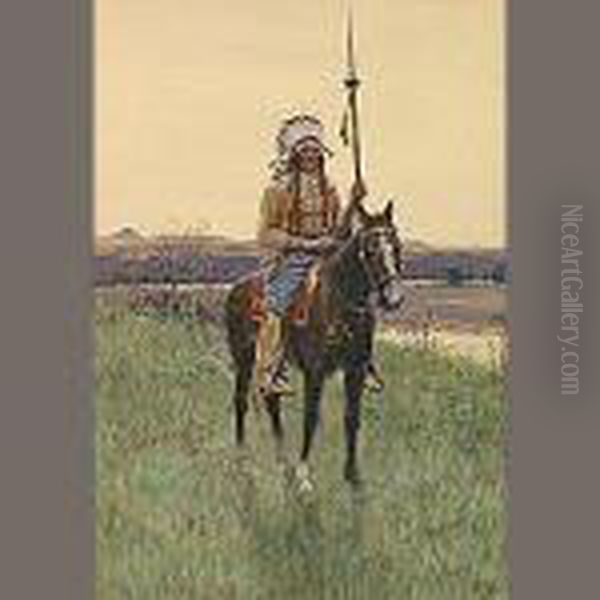

Southern Plains Indian Warrior is another significant work, demonstrating his skill in figure painting and detailed rendering of Native American attire and accoutrements. Its high auction price reflects the market's continued appreciation for Farny's work and his place within the genre of Western American art. Such paintings highlight his focus on the individual figure, presented with dignity and strength.

The Song of the Talking Wire (1904) is one of Farny's most iconic images. It depicts a Native American man, likely a Sioux, leaning against a telegraph pole in a winter landscape, his ear pressed to the wood as if listening to the humming wires. The image powerfully symbolizes the encounter between traditional Native culture and the encroaching technology of the modern world. It evokes themes of curiosity, isolation, and the profound changes sweeping across the West, handled with Farny's typical subtlety and emotional resonance.

In Pastures New shows a different aspect of his work, a more pastoral scene depicting Plains Indians with their horses in a lush, verdant landscape. It highlights his mastery of color and atmosphere, creating a sense of peace and harmony. His illustrations, such as Niu-ciu, the Old Chief - Zuñi created for The Century Magazine in 1882, demonstrate his ethnographic accuracy and skill in translating his observations into compelling published images. These works, among many others, solidify Farny's reputation as a master painter of the American West.

Farny and His Contemporaries

Henry Farny occupied a unique position within the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century American art. His career intersected with several important artistic circles and movements. His training in Düsseldorf connected him to a tradition shared by other prominent American artists like Albert Bierstadt and Worthington Whittredge, who also studied there. However, while Bierstadt often focused on grandiose, panoramic landscapes, Farny's Western scenes were typically more intimate and focused on human activity within the environment.

In Cincinnati, Farny was part of a vibrant artistic community that included his friends and fellow artists Frank Duveneck and John Henry Twachtman. Duveneck became associated with the Munich School's painterly realism, while Twachtman evolved into a leading American Impressionist. Farny maintained his distinct realistic style, influenced by Düsseldorf, setting him apart from the dominant trends pursued by his close associates. Robert Blum, another Cincinnati contemporary, also achieved success as a painter and illustrator, sometimes exploring exotic themes.

When considering artists specializing in the American West, Farny is often compared to Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell. Remington was known for his dramatic, action-packed depictions of cowboys, soldiers, and Native Americans, often emphasizing conflict and masculinity. Russell, based in Montana, focused heavily on cowboy life and the landscapes of the Northern Plains, working in a style that was often more anecdotal and rugged than Farny's. Farny's work generally offers a quieter, more contemplative, and arguably more sympathetic view of Native American life than either Remington or Russell, with a greater emphasis on ethnographic detail and peaceful scenes.

Farny's work also relates to the earlier tradition of artists documenting Native American life, such as George Catlin and Karl Bodmer, who traveled west decades earlier. While Catlin and Bodmer were pioneers in ethnographic recording, Farny benefited from advancements in photography and brought a more refined, academic painting technique to the subject. He can also be seen alongside the artists of the Taos Society, such as Joseph Henry Sharp, E. Irving Couse, and Oscar E. Berninghaus, who also specialized in Native American subjects, though their work often reflects a slightly later period and the distinct cultures and light of the Southwest.

In the broader context of American realism, Farny shares a commitment to truthful observation with figures like Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer, although their primary subjects differed. As an illustrator, he worked during a "Golden Age" alongside giants like Howard Pyle, contributing significantly to the visual culture disseminated through popular magazines and books. Farny's unique contribution lies in his synthesis of European academic skill, firsthand Western experience, and a consistent, empathetic focus on Native American subjects.

Later Life and Legacy

After his final trip west in 1894, Henry Farny spent the remaining two decades of his life working primarily in his Cincinnati studio. He continued to paint Native American subjects, drawing upon the wealth of sketches, photographs, artifacts, and memories accumulated during his travels. His reputation was well-established, and his paintings were highly sought after by collectors. He remained an active figure in the Cincinnati art scene, serving for a time as president of the Cincinnati Art Club, demonstrating his standing within the local community.

Farny passed away in Cincinnati on December 23, 1916. While highly regarded during his lifetime, his work, like that of many realist painters of his generation, experienced a period of relative obscurity during the mid-20th century as modernist aesthetics came to dominate the art world. However, beginning in the 1960s, there was a resurgence of interest in Western American art and historical realism. Farny's paintings were rediscovered and newly appreciated for their artistic quality, historical significance, and sensitive portrayal of Native American life.

Today, Henry Farny is recognized as one of the most important painters of the American West. His work is valued not only for its aesthetic appeal but also as a crucial visual record of Native American cultures during a critical period of transition. His commitment to accuracy, informed by direct observation and a collection of artifacts (many of which are now in museum collections), lends his work enduring ethnographic importance. More significantly, his consistent effort to portray his subjects with dignity and humanity offers a valuable counterpoint to the often-stereotyped representations prevalent during his time and since. His legacy is that of a skilled artist who used his talents to create a nuanced and sympathetic portrait of the American West and its first peoples.

Conclusion

Henry François Farny's life journey took him from revolutionary France to the burgeoning cities and vast landscapes of America. Shaped by unique childhood experiences with the Seneca people and rigorous artistic training in Europe, he developed a distinctive vision focused on the Native American inhabitants of the West. As both an illustrator and a painter, he created a body of work characterized by meticulous realism, careful observation, and profound empathy.

Avoiding the sensationalism common among many painters of the West, Farny offered quieter, more intimate glimpses into the daily lives, resilience, and dignity of his subjects during a time of immense upheaval. His paintings serve as valuable historical documents, rendered with ethnographic care, yet they transcend mere documentation through their artistic sensitivity and nuanced portrayal of the human condition. Henry Farny remains a vital figure in American art, a chronicler whose sympathetic eye captured the complexities of the changing West and preserved a respectful vision of its Native peoples for future generations.