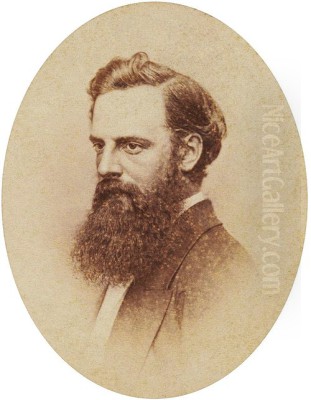

Nicholas Chevalier (1828-1902) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the art history of the 19th century. A truly cosmopolitan individual, his life and career spanned continents, from Russia to Switzerland, England, Australia, and New Zealand, leaving an indelible mark on the artistic representation of these diverse locales. His work, characterized by meticulous detail, a Romantic sensibility, and a keen eye for the topographical, provides invaluable visual records of a world undergoing rapid change during the Victorian era. This exploration delves into his multifaceted career, examining his origins, artistic development, major achievements, stylistic characteristics, and his enduring legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Nicholas Chevalier was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, on May 9, 1828. His parentage reflected a European blend; his father, Louis Chevalier, was Swiss, hailing from the canton of Vaud, and worked as a supervisor of estates for the influential Prince Wittgenstein, a prominent figure in the Russian court. His mother, Tatiana Ermolaeff, was Russian. This mixed heritage likely contributed to Chevalier's linguistic abilities and his adaptable nature, which would serve him well in his future travels.

The family relocated to Lausanne, Switzerland, around 1845, following his father's retirement. It was here that the young Chevalier began his formal artistic training. He initially pursued studies in architecture, attending the Imperial Academy of Arts in Munich from approximately 1848 to 1851. Munich, at this time, was a vibrant centre for the arts, and exposure to its academic traditions would have provided a solid foundation in drawing and composition. His architectural training, in particular, likely honed his precision and attention to structural detail, qualities evident in his later landscape and topographical works.

Seeking to broaden his skills, Chevalier moved to London around 1851. In the bustling metropolis, he studied lithography under the esteemed Ludwig Gruner, a German-born artist and adviser to Prince Albert. This period was crucial, as lithography was a popular medium for disseminating images, and proficiency in it offered practical career opportunities. He also undertook watercolour painting, a medium in which he would excel. For a brief period, he is also said to have studied painting in Paris, possibly encountering the work of prominent Salon artists, though details of this Parisian sojourn are less clear. His time in London also saw him gain employment as an illustrator for the Illustrated London News, a prestigious publication that would have further developed his skills in narrative composition and rapid sketching. He also reportedly designed a fountain for Osborne House, Queen Victoria's residence on the Isle of Wight, under Gruner's direction.

A desire for further artistic immersion led him to Rome in 1853, where he spent about a year. Italy, with its rich classical heritage and picturesque landscapes, was a traditional destination for aspiring artists. Here, he would have been exposed to the works of the Old Masters and the vibrant community of international artists. This period likely deepened his appreciation for landscape painting and the Romantic tradition, which often idealized nature and historical settings. The combination of rigorous German academic training, practical British illustrative experience, and the classical inspiration of Italy forged a versatile and skilled artist.

The Australian Sojourn: Gold, Art, and Exploration

The allure of the Australian gold rushes, which began in the early 1850s, proved irresistible to many, including Nicholas Chevalier. In late 1854 or early 1855, he set sail for Melbourne, Victoria, a city rapidly transforming due to the influx of wealth and migrants. While the prospect of gold may have been an initial motivator, Chevalier quickly found his artistic skills in high demand in the burgeoning colonial society.

Upon his arrival in Melbourne, he initially worked as a cartoonist for the newly established Melbourne Punch, a satirical magazine. His European training and illustrative experience made him a valuable asset. He also contributed illustrations to the Illustrated Australian News and other publications, capturing the life and landscapes of the colony. His ability to work across different media – oil, watercolour, and print – allowed him to engage with various aspects of the colonial art scene.

A significant achievement during this period was his design for the first postage stamp of the newly independent colony of Victoria in 1854, featuring a portrait of Queen Victoria. This commission underscored his growing reputation and his ability to undertake official and prestigious projects. He became an active member of Melbourne's artistic community, exhibiting his works and contributing to the cultural development of the city. He was a founding member of the Victorian Society of Fine Arts in 1856, which later became the Victorian Academy of Arts.

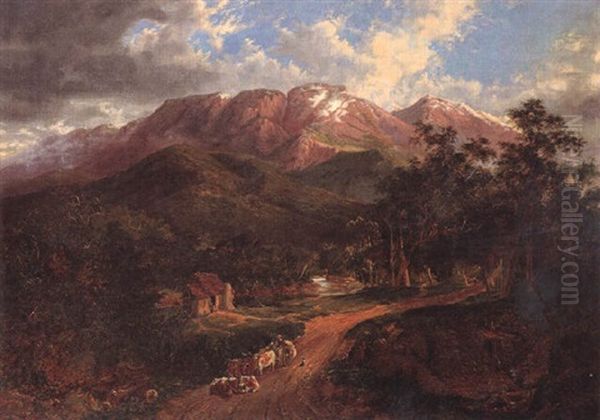

Chevalier's most enduring contributions from his Australian period are his landscape paintings. He undertook several expeditions into the Victorian countryside, often accompanying scientific or survey parties. These journeys allowed him to capture the unique beauty and ruggedness of the Australian bush. His works from this time, such as The Buffalo Ranges, Victoria (1864) and Mount Arapiles and the Mitre Rock (1864), are celebrated for their detailed realism, atmospheric effects, and their ability to convey the grandeur of the Australian landscape. He worked alongside other prominent colonial artists like Eugene von Guérard, a fellow European-trained painter known for his sublime depictions of the Australian wilderness, and Louis Buvelot, whose more naturalistic approach influenced the later Heidelberg School. Chevalier's paintings often combined topographical accuracy with a Romantic sensibility, appealing to both colonial pride and European aesthetic tastes. He also painted significant historical events, such as The Meeting of the Burke and Wills Expedition with the Natives near Cooper's Creek (1862), a subject also tackled by contemporary William Strutt.

Documenting New Zealand: A Painter's Paradise

In 1865, Nicholas Chevalier extended his colonial artistic explorations to New Zealand. He arrived in Dunedin, Otago, a region also experiencing a gold rush. His reputation preceded him, and he quickly found patronage and opportunities to document the dramatic landscapes of the South Island. He spent approximately a year in New Zealand, a period that proved to be exceptionally productive and resulted in some of his most acclaimed works.

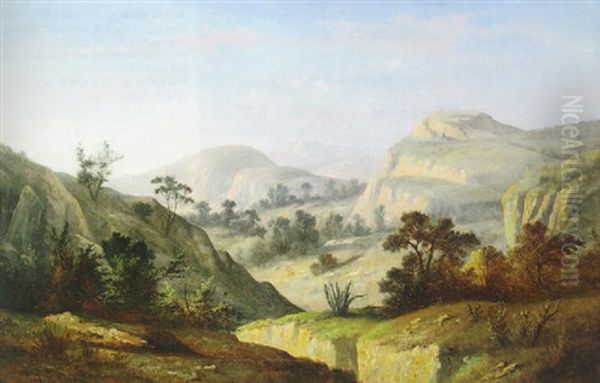

Chevalier was captivated by the majestic scenery of New Zealand – its towering mountains, deep fiords, lush forests, and pristine lakes. He undertook arduous journeys to remote areas, often sketching en plein air and later developing these sketches into finished watercolours and oil paintings in his studio. His New Zealand works are characterized by their vibrant colours, meticulous detail, and a sense of awe inspired by the natural environment.

Among his notable New Zealand paintings are views of Lake Wakatipu, the Otira Gorge, Milford Sound, and the Southern Alps. These works were not merely picturesque representations; they also served as important visual records of a landscape that was still largely unfamiliar to European audiences. His paintings helped to shape perceptions of New Zealand and contributed to its growing reputation as a land of extraordinary natural beauty. He often travelled with prominent figures, including the geologist Sir Julius von Haast, which provided him access to remote and scientifically interesting locations.

His New Zealand landscapes were exhibited both locally and internationally, further enhancing his reputation. He was one of the first professional artists to extensively document the South Island's interior, and his work stands alongside that of other colonial New Zealand artists like John Gully and Alfred Sharpe, though Chevalier's European training often lent his work a greater degree of technical polish and academic sophistication. His watercolours, in particular, were praised for their delicacy and precision. The New Zealand government recognized the value of his work, purchasing several of his paintings for public collections. This period solidified Chevalier's status as a leading colonial artist, capable of capturing the unique character of diverse landscapes within the British Empire.

Voyage with Royalty: The HMS Galatea Expedition

A pivotal moment in Nicholas Chevalier's career came in 1867 when he was invited to join Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh (the second son of Queen Victoria), on his world tour aboard HMS Galatea. The Duke was undertaking the first-ever royal tour of Australia, and Chevalier was selected as the official artist to accompany the voyage. This prestigious appointment provided him with an unparalleled opportunity to travel extensively and document the diverse cultures and landscapes encountered during the tour.

The HMS Galatea expedition, which lasted from 1867 to 1868 for Chevalier, took him from Australia to New Zealand, Tahiti, Hawaii, Japan, China, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and India. Throughout this journey, Chevalier was tasked with creating a visual record of the places visited, the official ceremonies, and the notable events. He produced a vast number of sketches, watercolours, and oil paintings, capturing everything from grand state receptions and naval displays to exotic landscapes, local customs, and portraits of indigenous peoples.

His works from this period are remarkable for their ethnographic detail and their ability to convey the excitement and novelty of these encounters. Paintings such as Arrival of HMS Galatea at Port Jackson and various scenes from the Pacific islands and Asia demonstrate his skill in handling complex compositions and his keen observational abilities. His depictions of Japan, a country that had only recently opened to the West, were particularly significant, offering some of the earliest artistic impressions of Japanese life and scenery by a Western artist of his calibre.

The royal connection brought Chevalier significant exposure and prestige. His works were exhibited in London upon his return and were widely reproduced, further popularizing his art. The experience of travelling with the Duke of Edinburgh also provided him with valuable social connections and access to elite circles, which would be beneficial for his subsequent career in England. This voyage cemented his reputation as an artist of empire, adept at chronicling the reach and diversity of British influence across the globe. His ability to adapt his style to suit different subjects, from formal state occasions to intimate landscape studies, was a testament to his versatility.

Return to England and Royal Patronage

Following the conclusion of his duties with the HMS Galatea tour, Nicholas Chevalier returned to England in 1869, settling in London. His experiences abroad, particularly his association with the Duke of Edinburgh, provided a strong foundation for establishing his career in the heart of the British art world. He began exhibiting regularly at the Royal Academy of Arts and other prominent London galleries.

Queen Victoria herself took a keen interest in Chevalier's work, particularly the paintings and sketches produced during the Galatea voyage. She commissioned several works from him, including paintings based on his tour sketches and portraits. One notable commission was The Marriage of the Duke of Edinburgh (1874), depicting the wedding of Prince Alfred to Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia. This large-scale, complex composition demonstrated his ability to handle grand ceremonial subjects and further solidified his standing as a favoured artist of the royal family.

Chevalier's subjects in England were diverse. He continued to paint landscapes, often inspired by his travels, but also undertook portraiture and genre scenes. His style remained rooted in the academic tradition, emphasizing careful draughtsmanship, balanced composition, and a polished finish. While he was aware of emerging modernist trends, such as Impressionism, his own work largely adhered to the established conventions favoured by the Royal Academy and its patrons. Artists like Sir Edwin Landseer, known for his animal paintings and royal favour, Frederic Leighton, a leading figure of High Victorian art, and John Everett Millais, a former Pre-Raphaelite who achieved immense popular success, were among the prominent figures in the London art scene with whom Chevalier would have exhibited and interacted. William Powell Frith, famous for his panoramic scenes of Victorian life like Derby Day, represented another facet of the popular academic art of the era.

In 1882, Chevalier was appointed as the London adviser to the National Gallery of New South Wales, a role that allowed him to maintain his connections with Australia and contribute to the development of its public art collections. He held this position until his death, using his expertise to recommend acquisitions and support Australian artists. Despite his success in England, his experiences in Australia and New Zealand remained a significant part of his artistic identity, and he often revisited colonial themes in his work. He passed away in London on March 15, 1902, leaving behind a substantial body of work that documents a remarkable life of travel and artistic endeavour.

Artistic Style and Influences

Nicholas Chevalier's artistic style was a product of his diverse training and extensive travels. At its core, his work is characterized by a commitment to detailed realism and topographical accuracy, likely a legacy of his architectural studies and his work as an illustrator. This precision is evident in his landscapes, where geological formations, botanical details, and atmospheric conditions are rendered with meticulous care.

However, his realism was often infused with a Romantic sensibility. He had a talent for capturing the sublime and picturesque qualities of nature, imbuing his landscapes with a sense of grandeur and atmosphere. This is particularly evident in his depictions of the Australian wilderness and the dramatic scenery of New Zealand, where he sought to convey both the physical reality of the landscape and the emotional response it evoked. His use of light and colour was often carefully controlled to create specific moods, from the golden haze of an Australian sunset to the crisp clarity of alpine air.

Chevalier was proficient in both oil painting and watercolour. His oils are typically characterized by a smooth, polished finish, reflecting academic conventions. His watercolours, on the other hand, often display a greater degree of spontaneity and freshness, particularly his on-the-spot sketches. He was adept at using watercolour to capture fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, and his works in this medium are highly regarded for their delicacy and technical skill.

His early training in Munich would have exposed him to the German Romantic landscape tradition, exemplified by artists like Caspar David Friedrich, though Chevalier's work is generally less overtly symbolic. His time in London and his association with Ludwig Gruner grounded him in the practicalities of printmaking and illustration. The influence of British watercolourists like J.M.W. Turner, though perhaps indirect, can be seen in his atmospheric effects. In Australia, he was a contemporary of Eugene von Guérard, whose meticulous, often panoramic, landscapes shared some similarities with Chevalier's approach, although von Guérard's work often carried stronger undertones of scientific inquiry and Humboldtian ideals. Louis Buvelot, another key figure in Australian landscape painting, favoured a more naturalistic, Barbizon-influenced style that contrasted somewhat with Chevalier's more detailed and sometimes idealized approach. His wife, Caroline Wilkie, whom he married in 1855, was the niece of the famous Scottish genre painter Sir David Wilkie, and this connection may have provided further artistic stimulus, particularly in the realm of genre and narrative painting.

Key Works and Their Significance

Nicholas Chevalier's oeuvre is extensive, but several key works stand out for their artistic merit and historical importance.

The Buffalo Ranges, Victoria (1864) is one of his most iconic Australian landscapes. This panoramic oil painting captures the majestic beauty of the Victorian high country with remarkable detail and atmospheric depth. It exemplifies his ability to combine topographical accuracy with a Romantic appreciation for the grandeur of nature. The painting was highly acclaimed in its time and helped to establish the Buffalo Ranges as a significant scenic destination.

Mount Arapiles and the Mitre Rock (1864) is another important Australian work, showcasing a distinctive geological formation in western Victoria. Chevalier's rendering of the dramatic rock structures and the surrounding landscape is both precise and evocative, highlighting the unique character of the Australian environment. This work, like The Buffalo Ranges, contributed to the colonial project of mapping and understanding the new continent.

His New Zealand works, such as View of Lake Wakatipu with the Remarkables (c. 1866) and Otira Gorge, West Coast, South Island, New Zealand (c. 1866), are celebrated for their depiction of the country's stunning natural scenery. These paintings, often executed in watercolour with remarkable finesse, captured the pristine beauty of areas that were then remote and largely inaccessible. They played a crucial role in introducing New Zealand's landscapes to a wider international audience.

From the HMS Galatea voyage, works like The Duke of Edinburgh Visiting the Emperor of Japan (c. 1869) and various scenes of Polynesian life are significant. These paintings offer valuable visual records of diplomatic encounters and cultural observations during a period of increasing global interaction. They demonstrate Chevalier's skill as a documentary artist, capable of capturing the nuances of different cultures and environments.

His later royal commissions, such as The Marriage of H.R.H. The Duke of Edinburgh and H.I.H. The Grand Duchess Marie Alexandrovna of Russia at the Winter Palace, St Petersburg (1874), showcased his ability to handle complex, multi-figure compositions and grand ceremonial occasions. These works cemented his status as an artist favoured by the British royal family and demonstrated his versatility beyond landscape painting. These representative pieces collectively illustrate the breadth of Chevalier's talent and the diverse geographical and thematic scope of his art.

Connections and Contemporaries

Throughout his peripatetic career, Nicholas Chevalier interacted with a wide array of artists, patrons, and influential figures, shaping and being shaped by the artistic currents of his time. His early studies placed him in contact with the academic traditions of Munich and the printmaking world of London under Ludwig Gruner.

In Australia, he was a prominent figure in the Melbourne art scene. He exhibited alongside and knew artists such as Eugene von Guérard, whose meticulously detailed landscapes often shared a similar ambition in depicting the grandeur of the Australian continent. Louis Buvelot, a Swiss-born artist like Chevalier's father, brought a more naturalistic, Barbizon-influenced style to Australian landscape painting and was another key contemporary. William Strutt, an English artist, was also active in Victoria during a similar period, known for his historical paintings and depictions of colonial life, including scenes from the Burke and Wills expedition, a subject Chevalier also tackled. S.T. Gill, the renowned watercolourist and illustrator, documented the gold rush era with a more popular, anecdotal style, providing a different perspective on colonial life compared to Chevalier's more formal approach.

During his time in New Zealand, Chevalier's work can be contextualized alongside that of John Gully, a largely self-taught artist who became famous for his romantic watercolours of New Zealand landscapes, and Alfred Sharpe, another significant landscape painter active in the country. Chevalier's professional training often set his work apart in terms of technical execution.

His involvement with the HMS Galatea tour brought him into the orbit of Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, and subsequently Queen Victoria, leading to significant royal patronage. In London, he exhibited at the Royal Academy, placing his work in the company of the era's leading British artists. Figures such as Sir Edwin Landseer, a favourite of Queen Victoria; Frederic Leighton, President of the Royal Academy and a proponent of classical subjects; John Everett Millais, who transitioned from Pre-Raphaelitism to become a highly successful society painter; and William Powell Frith, chronicler of Victorian social scenes, were all part of this milieu. While Chevalier may not have achieved the same level of fame as some of these titans, he was a respected member of this artistic establishment. His marriage to Caroline Wilkie, niece of the celebrated Scottish painter Sir David Wilkie, also connected him to an important artistic lineage. These connections underscore Chevalier's ability to navigate diverse artistic and social circles across multiple continents.

Personal Glimpses and Anecdotes

While much of Nicholas Chevalier's life is understood through his artistic output and official appointments, some personal glimpses and anecdotes offer a more rounded picture of the man. His multilingual abilities – fluent in Russian, French, German, and English – were undoubtedly a significant asset in his international career, facilitating his studies, travels, and interactions with diverse patrons and communities.

His decision to emigrate to Australia, ostensibly drawn by the gold rush, suggests an adventurous spirit. While he didn't strike it rich prospecting, his artistic talents found fertile ground in the rapidly developing colony. This adaptability and resourcefulness were recurring themes in his life. His willingness to undertake arduous journeys into the Australian outback and the remote regions of New Zealand, often with basic amenities, speaks to his dedication as a landscape artist and his physical resilience.

The invitation to join the Duke of Edinburgh's world tour was a life-changing opportunity, but it also demanded considerable stamina and diplomatic skill. As the official artist, he would have been expected to produce a consistent output of high-quality work under varying and sometimes challenging conditions, all while navigating the protocols of a royal entourage. His diaries and letters from this period, where available, provide insights into the day-to-day realities of such a voyage.

His marriage to Caroline Wilkie in Melbourne in 1855 was a partnership that lasted nearly five decades. Caroline was herself an artist, though less is known about her independent career. It is plausible that they shared artistic interests and supported each other's endeavours. The fact that Chevalier maintained his role as London adviser to the National Gallery of New South Wales for two decades until his death indicates a lasting connection to Australia and a commitment to fostering its cultural institutions, even after establishing himself in London. One charming, if perhaps apocryphal, story suggests that his initial design for the Victorian postage stamp was so well-received that it helped secure his reputation in the colony almost immediately upon his arrival. These fragments help to humanize a figure often seen primarily through the lens of his formal achievements.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

Nicholas Chevalier's legacy is multifaceted. He is recognized as one of the most significant artists working in Australia and New Zealand during the colonial period. His landscapes provided invaluable early visual records of these regions, shaping both local and international perceptions of their natural environments. In Australia, his work is seen as part of the broader movement of colonial artists who sought to capture the unique character of the continent, bridging European artistic traditions with new and unfamiliar subject matter. His contributions to publications like Melbourne Punch and the Illustrated Australian News also highlight his role in the development of visual culture in the colonies.

In New Zealand, his paintings, particularly his watercolours of the South Island, are prized for their beauty and historical importance. He was among the first professionally trained artists to extensively document these landscapes, and his work remains a touchstone for understanding the 19th-century European encounter with Maori land.

His role as the official artist on the HMS Galatea tour cemented his reputation as an artist of the British Empire. The vast body of work produced during this voyage offers a unique visual chronicle of global travel and diplomatic encounters in the mid-Victorian era. His subsequent royal patronage in England further underscores his success within the established art world of his time.

Art historically, Chevalier is generally positioned within the academic and Romantic traditions of the 19th century. His meticulous attention to detail, combined with an ability to convey atmospheric effects and a sense of the sublime, aligns him with these movements. While he was not an avant-garde innovator in the vein of the Impressionists or other modernist pioneers who were his contemporaries in Europe, his technical skill and the breadth of his subject matter are widely acknowledged.

Critically, his work has been consistently praised for its draughtsmanship and compositional strength. Some later critics may have found his style somewhat conventional compared to more radical artistic developments, but his historical significance as a documentary artist and a skilled painter of diverse global landscapes is undisputed. His paintings are held in major public collections in Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere, attesting to their enduring appeal and importance. Nicholas Chevalier remains a key figure for understanding the art and visual culture of the 19th-century colonial world and the role of artists in documenting and interpreting an era of exploration and imperial expansion.