Samuel Thomas Gill, often affectionately known as S.T.G., stands as one of the most significant visual chroniclers of Australian colonial life, particularly during the tumultuous gold rush era. His prolific output, primarily in watercolour and lithography, offers an invaluable and often spirited glimpse into the landscapes, people, and burgeoning society of mid-19th century South Australia and Victoria. While perhaps not celebrated for grand artistic innovation in the European sense, Gill's sharp observational skills, combined with a flair for narrative and occasional satire, secured his place as a vital documentary artist whose work continues to inform and fascinate.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Samuel Thomas Gill was born in Perriton, Minehead, Somerset, England, on May 21, 1818. His father, Reverend Samuel Gill, was a Baptist minister who also ran a school, and his mother, Winifred Oke, was herself an amateur painter. This background likely provided the young Gill with both education and an early exposure to art. He received formal training in London, initially apprenticed to a heraldic painter and later working for the Hubard Gallery, a producer of silhouette portraits. This early work honed his skills in draughtsmanship and capturing likenesses, foundational elements that would serve him well throughout his career.

Seeking better prospects and perhaps adventure, the Gill family, including Samuel, his parents, and siblings, emigrated to the fledgling colony of South Australia. They arrived in Adelaide aboard the Caroline on December 17, 1839. The colony was barely three years old, a raw environment brimming with challenges and opportunities. Gill quickly set about establishing himself as an artist in this new land, eager to capture its unique character.

Establishing a Career in South Australia

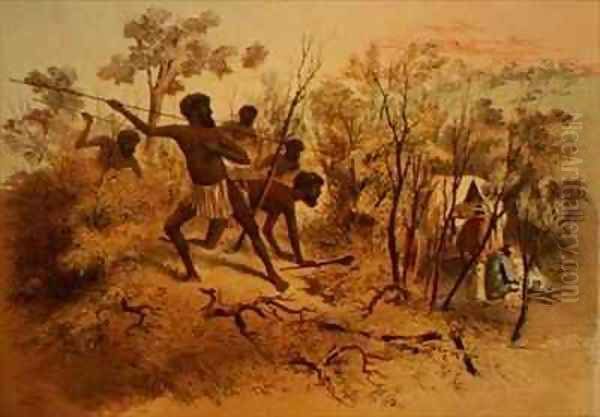

In Adelaide, Gill opened a studio on Gawler Place. He advertised his services, offering to produce portraits, paint residences and animals, and capture the local scenery. His early South Australian works included street scenes of Adelaide, views of the surrounding countryside, and depictions of the activities of the colonists and the local Kaurna Aboriginal people. These works demonstrated his keen eye for detail and his ability to render the specific light and atmosphere of the Australian landscape, which differed significantly from that of England.

His skills were recognized, and he gained commissions. He produced topographical views that were valuable for a society keen to understand and map its new territory. Works from this period, such as views of Glen Osmond or early Adelaide streetscapes, show a competent handling of watercolour and a documentary intent. He was capturing the birth of a city and the interactions between its inhabitants and the environment. His depictions of Aboriginal people, while viewed through a 19th-century European lens, are nonetheless important records, though they require careful contextual interpretation today.

A significant and harrowing experience during his South Australian years was his participation in John Horrocks's expedition to the north-west of the Flinders Ranges in 1846. Gill joined as the expedition's artist, tasked with documenting the journey into unexplored territory. The expedition met with disaster when Horrocks was accidentally shot in the face during a hunting incident involving a camel. Gill tended to the injured leader and documented aspects of the difficult return journey. Horrocks later died from his injuries. Gill's sketches from this expedition provide a stark visual account of the perils of exploration in the Australian interior.

The Artist of the Goldfields

The discovery of gold in Victoria in 1851 triggered a massive rush that transformed the Australian colonies. Drawn by the potential for new subjects and perhaps new patrons among the suddenly wealthy, Gill moved to Victoria in 1852. This move marked the beginning of the most famous and prolific phase of his career, earning him the enduring title "Artist of the Goldfields." He immersed himself in the chaotic, energetic, and often harsh life of the diggings in areas like Ballarat, Bendigo, and Mount Alexander.

Gill's watercolours and sketches from the Victorian goldfields are remarkable for their immediacy and vitality. He captured the full spectrum of life: diggers panning for gold, the makeshift tents and stores, the boisterous hotels, the successes and failures, the moments of camaraderie and despair. He didn't just paint landscapes; he painted human activity within those landscapes. His figures are lively, often depicted with a degree of caricature that highlights their types and activities, reminiscent perhaps of the British satirical tradition of artists like Thomas Rowlandson or George Cruikshank.

His work during this period was widely disseminated through lithography. Series like Sketches of the Victoria Gold Diggings and Diggers As They Are (1852-53) and The Australian Sketchbook (1855) proved immensely popular both in Australia and England. These prints provided vivid impressions of the gold rush for a public hungry for information and images. Works such as Concert Room, Charlie Napier Hotel, Ballarat or Digger's Licence Inspection capture the social dynamics and tensions of the goldfields with an unparalleled directness. Gill became the definitive visual interpreter of this pivotal era.

Style, Technique, and Themes

Gill primarily worked in watercolour, pencil, and ink, often preparing his sketches on the spot and later working them up into finished watercolours or designs for lithographs. His style is characterized by fluid lines, keen observation of detail, and an emphasis on narrative content. While capable of accurate topographical representation, his most compelling works are those filled with human figures engaged in everyday activities. He had a knack for capturing posture, gesture, and expression, bringing his scenes to life.

His use of watercolour was often direct and economical, using washes to establish atmosphere and tone, with details added in pen or finer brushwork. His palette reflected the Australian environment – the earthy tones of the diggings, the distinctive colours of the eucalyptus trees, and the bright, harsh sunlight. Compared to the more formal, often Romantic or Sublime landscapes being produced by contemporaries like Conrad Martens or Eugene von Guérard, Gill's work was grittier, more focused on the human element and the social landscape.

Thematically, Gill's work revolved around colonial life. He documented urban development in Adelaide and later Melbourne and Sydney, the rigours of exploration, the pastoral industry (like his Overlanders series), and, most famously, the gold rush. His depictions often contained subtle social commentary or humour, observing the pretensions, hardships, and eccentricities of colonial society. His portrayal of Indigenous Australians evolved over time but largely reflected the prevailing colonial attitudes of his era, serving as historical documents that require critical engagement.

Later Years and Decline

Despite the popularity of his goldfields prints, sustained financial success eluded Gill. He moved to Melbourne around 1854 and continued to produce works depicting city life, sporting events, and public occasions. He later spent time in Sydney from around 1856, again capturing the life of the city. However, the market for his style of illustrative work perhaps diminished as photography became more widespread and artistic tastes shifted. Contemporaries like Nicholas Chevalier, who worked in oils and documented grander events, or the emerging landscape focus of artists like Louis Buvelot, represented different artistic directions.

Gill returned to Melbourne in the mid-1860s. His circumstances appear to have gradually declined. While he continued to produce work, commissions became scarcer. He struggled with poverty and, reportedly, alcoholism. His later works sometimes lack the vibrancy of his goldfields peak, yet they still retain his characteristic observational skill. He produced architectural views and documented events like the visit of the Duke of Edinburgh. He remained an artist committed to recording the world around him, even as his personal fortunes waned.

The contrast between the lively energy of his best-known works and the sadness of his final years is stark. On October 27, 1880, Samuel Thomas Gill collapsed on the steps of the Melbourne General Post Office. He was taken to hospital but was pronounced dead. The official cause was given as "rupture of an aneurism of the aorta." He died penniless and was buried in a pauper's grave in the Melbourne General Cemetery. It was a tragic end for an artist who had so vividly captured the spirit of his time.

Collaborations, Influence, and Artistic Context

While direct collaborations seem rare, Gill operated within a context of other colonial artists. His work can be compared and contrasted with figures like George French Angas, who also documented early South Australia, including its Indigenous inhabitants, often with a more ethnographic focus. William Strutt, another artist active in Victoria during the gold rush, produced more detailed, sometimes historical narrative paintings, offering a different perspective on events like the Black Thursday bushfires.

Gill's influence lies less in founding an artistic school and more in establishing a tradition of documentary and illustrative art in Australia. His approach, focusing on everyday life and social observation, prefigures aspects of later Australian art movements that sought to capture a distinctly national character. His work provided a visual vocabulary for representing Australian colonial experience that resonated widely. While not directly influencing the plein-air painters of the Heidelberg School like Tom Roberts or Arthur Streeton, Gill's commitment to depicting Australian life and landscape forms part of the broader narrative of Australian art history.

Internationally, his work belongs to a tradition of topographical and illustrative art that flourished with colonial expansion. His focus on social types and narrative echoes aspects of European artists known for social commentary, such as William Hogarth in 18th-century England or Honoré Daumier in 19th-century France, although Gill's satire was generally gentler and less politically charged. His primary contribution remains his unparalleled record of Australian colonial society, particularly in South Australia and during the Victorian gold rush.

Exhibitions and Historical Reputation

During his lifetime, Gill exhibited his works and sold prints, achieving considerable contemporary recognition, especially for his goldfields series. However, formal exhibitions in the grand institutional sense may not have been his primary mode of dissemination; the print market was crucial for his reach. His work was known in London through publications like the Illustrated London News and his own print series.

Posthumously, Gill's reputation underwent a significant re-evaluation. Initially somewhat overlooked by art historians focused on oil painting and landscape traditions, his work gained increasing recognition from the early 20th century onwards for its immense historical value. Historians and curators began to appreciate his sketches and watercolours not just as illustrations, but as vital primary source documents offering unique insights into the social history of colonial Australia.

Today, Samuel Thomas Gill is widely acknowledged as a major figure in Australian colonial art. His works are held in the collections of all major Australian public galleries, including the National Gallery of Australia, the National Gallery of Victoria, the Art Gallery of South Australia, the State Library Victoria, and the State Library of New South Wales. Numerous exhibitions have been dedicated to his work, reassessing his artistic merits alongside his documentary importance. While debates continue about the aesthetic qualities of his art relative to contemporaries like von Guérard or Martens, his unique contribution as a visual chronicler is undisputed. He remains the quintessential "Artist of the Goldfields" and a key figure for understanding 19th-century Australia.

Legacy and Conclusion

Samuel Thomas Gill's legacy is twofold. Artistically, he was a skilled watercolourist and draughtsman with a remarkable ability to capture the energy and detail of everyday life. His compositions are often lively and informative, demonstrating a strong narrative sense and a keen eye for human character, sometimes infused with gentle humour or satire. He mastered the art of the sketch and the watercolour as tools for immediate reportage, bringing the colonial experience to life for a wide audience through accessible prints.

Historically, his legacy is perhaps even more profound. Gill left behind an extensive visual record of a transformative period in Australian history. His images of Adelaide's early years, the perils of exploration, and particularly the vibrant chaos of the Victorian goldfields are indispensable resources for understanding the nation's past. They offer glimpses into the lives of ordinary and extraordinary people – diggers, merchants, Indigenous Australians, explorers, families – navigating the challenges and opportunities of a new society.

Despite the hardships of his later life and his tragic death, Samuel Thomas Gill's work endures. He provided a unique window onto the world of colonial Australia, capturing its landscapes, its people, and its defining moments with an immediacy and insight that continues to engage viewers today. He remains a pivotal figure, celebrated not just as an artist, but as a crucial witness and chronicler of his time. His sketches, watercolours, and lithographs are more than just pictures; they are vital fragments of Australian history.