Lazar Markovich Lissitzky, known universally as El Lissitzky, stands as a colossus in the landscape of 20th-century art and design. Born on November 23, 1890, in Pochinok, a small Jewish community near Smolensk, Russia, and raised primarily in Vitebsk, Lissitzky's life and career traversed some of the most turbulent and transformative decades in modern history. He was not merely an artist in the traditional sense; he was a polymath – a painter, architect, graphic designer, typographer, photographer, and theorist whose innovative spirit fundamentally reshaped visual culture. His work became a crucial conduit between the radical experiments of the Russian avant-garde and the burgeoning modernist movements in Western Europe, leaving an indelible mark that continues to resonate today.

Lissitzky's journey was one of constant exploration and synthesis. He absorbed influences from diverse sources, navigated complex political terrains, and relentlessly pushed the boundaries of artistic expression. From his early engagement with Jewish cultural revival to his pivotal role in Suprematism and Constructivism, and his later contributions to Soviet propaganda, Lissitzky's oeuvre reflects a dynamic interplay between artistic formalism, technological possibility, and social aspiration. He envisioned art not as a detached aesthetic pursuit but as an active force capable of shaping consciousness and constructing a new world.

Early Life, Jewish Identity, and Formative Education

Lissitzky's upbringing within a Jewish family in the Pale of Settlement profoundly shaped his early outlook. While aspiring to study art, he faced institutional barriers; his application to the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts was rejected, likely due to the quotas limiting Jewish student admissions. This setback, however, redirected his path internationally. In 1909, he traveled to Germany to study architectural engineering at the Technische Hochschule in Darmstadt, a decision that exposed him to European culture and burgeoning modernist ideas.

His years in Darmstadt (1909-1914) were formative. He travelled across Europe, sketching architecture and immersing himself in diverse artistic currents. The outbreak of World War I forced his return to Russia in 1914. He continued his studies in Moscow and soon became involved in the Jewish cultural renaissance movement. Working alongside artists like Issachar Ber Ryback, he participated in ethnographic expeditions to document traditional synagogue art and Jewish folk traditions.

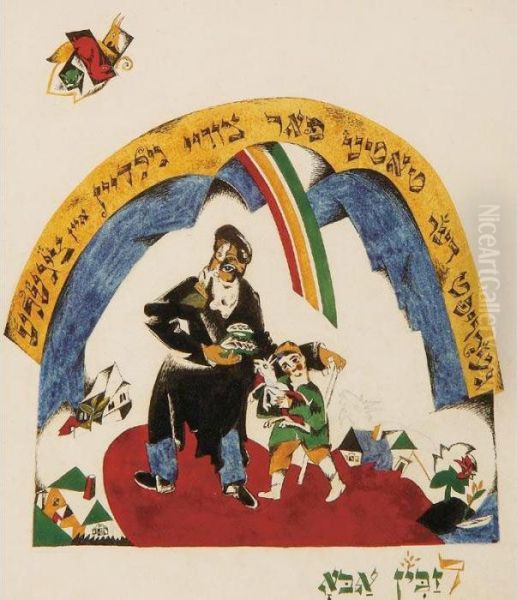

This period saw Lissitzky illustrating Yiddish children's books, such as "Sikhes Kholin" (An Everyday Conversation) and the famous "Had Gadya" (One Kid Goat) Passover song. These early works, often incorporating Hebrew lettering and elements of folk art, demonstrate his initial focus on integrating modern artistic sensibilities with his cultural heritage. They reveal a commitment to using art for cultural preservation and education, a precursor to his later belief in art's broader social function. His collaborators during this phase also included figures associated with the Kultur-Lige movement in Kiev.

Vitebsk: The Crucible of Suprematism and Proun

A pivotal moment arrived in 1919 when Marc Chagall, another prominent Jewish artist from Vitebsk and then Commissioner of Artistic Affairs for the city, invited Lissitzky to teach graphic arts, printing, and architecture at the newly established People's Art School. Vitebsk, under Chagall's leadership, had become a vibrant hub of avant-garde activity. However, the arrival of Kazimir Malevich later that year dramatically shifted the school's artistic direction and Lissitzky's own trajectory.

Malevich, the founder of Suprematism – an art movement dedicated to pure geometric abstraction and the "supremacy of pure artistic feeling" – quickly gained influence among the students and faculty. Lissitzky fell deeply under Malevich's spell, abandoning his earlier figurative and culturally specific work to embrace the radical abstraction of Suprematism. He became a fervent disciple and collaborator, joining Malevich's UNOVIS group (Affirmers of the New Art).

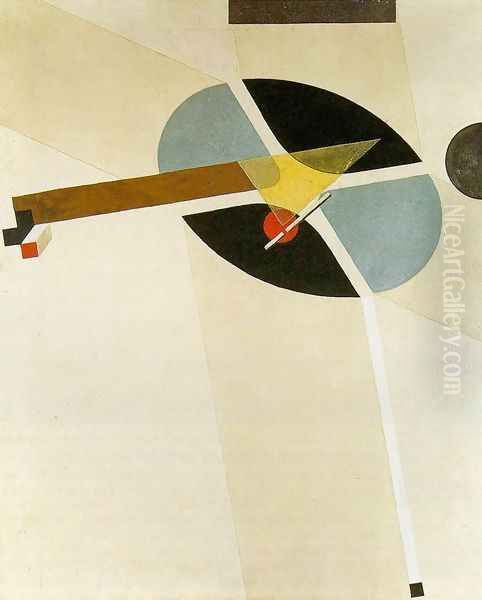

It was during this intense period in Vitebsk that Lissitzky developed his most significant conceptual contribution: the Proun (pronounced "pro-oon"). An acronym for the Russian "proekt utverzhdeniia novogo" (Project for the Affirmation of the New), Proun represented Lissitzky's unique synthesis of painting, architecture, and sculpture. He described Proun as "the station where one changes from painting to architecture." These works were abstract, multi-dimensional compositions exploring geometric forms in dynamic spatial relationships, often appearing as axonometric projections of imagined structures. They were not merely paintings but blueprints for a new spatial reality, embodying the transition from planar art to volumetric construction.

Constructivism and the Revolutionary Impulse

While deeply influenced by Malevich's Suprematism, Lissitzky's vision soon aligned more closely with the emerging principles of Constructivism. Spearheaded by artists like Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova, Constructivism rejected the notion of "art for art's sake" advocated by Malevich. Instead, it championed art as a practical tool for social construction, integrated into everyday life and serving the goals of the new Communist society. The artist was envisioned as an engineer, designing functional objects and communication systems for the collective good.

Lissitzky embraced this ethos wholeheartedly. His work from this period aimed to be utilitarian, communicative, and socially relevant. Perhaps the most iconic example is his 1919 lithograph, Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge. This starkly powerful abstract poster used simple geometric forms – a dynamic red triangle piercing a static white circle – to symbolize the Bolsheviks' struggle against the counter-revolutionary White Army during the Russian Civil War. It demonstrated Lissitzky's genius for translating complex political messages into a universally accessible, visually arresting language, becoming a landmark of political graphic design.

His commitment to Constructivist principles extended beyond graphic art. He envisioned architecture and design as integral components of the new social order, capable of organizing space and influencing behavior. The Proun concept evolved, becoming less about pure abstraction and more about potential real-world applications in architecture and exhibition design.

Berlin: Bridging East and West

In late 1921, Lissitzky's role expanded significantly when he was sent to Berlin as an unofficial cultural emissary for the Soviet state. Germany, particularly Berlin, was a major center for international artistic exchange in the post-war era. Lissitzky's mission was to establish connections between Russian avant-garde artists and their Western counterparts. He quickly became a vital link, disseminating Constructivist ideas and absorbing influences from European movements like Dada and De Stijl.

His time in Berlin was incredibly productive. He co-founded, with the Russian writer Ilya Ehrenburg, the influential trilingual (Russian, German, French) journal Veshch/Gegenstand/Objet (Object). Though short-lived, the journal served as a platform for promoting Constructivist ideals internationally, showcasing work by Russian and European artists and advocating for an art integrated with technology and social life.

Lissitzky actively engaged with key figures of the European avant-garde. He developed a close friendship and collaborative relationship with the Dada artist Kurt Schwitters, known for his Merz collages and constructions. He interacted frequently with Theo van Doesburg, the leading figure of the Dutch De Stijl movement, whose principles of geometric abstraction and functional design resonated with Lissitzky's own. He also established connections with László Moholy-Nagy, a fellow polymath who would soon become a key figure at the Bauhaus, sharing interests in photography, typography, and new materials. Lissitzky's presence significantly impacted the Bauhaus, particularly its shift towards a more functionalist, industry-oriented approach.

Further solidifying his role as an international connector, Lissitzky collaborated with the French Dadaist and Surrealist Jean Arp (also known as Hans Arp) on the book Die Kunstismen (The Isms of Art, 1925), a survey of recent art movements. He also maintained contact with other Russian émigré artists like the sculptor Ossip Zadkine. During this period, an anecdote arose involving fellow Russian artist Naum Gabo, who reportedly grew suspicious of Lissitzky after finding a Cheka (Soviet secret police) stamp in his Berlin studio, though this remains largely unsubstantiated speculation about Lissitzky's political affiliations.

Innovations in Typography and Graphic Design

Lissitzky's contributions to graphic design and typography were revolutionary and remain profoundly influential. He treated type not merely as a carrier of text but as an active visual element, a building block in the overall composition. He championed the use of sans-serif fonts for their clarity and modernity, employed dynamic asymmetrical layouts, and experimented with scale, weight, and orientation of type to create visual rhythm and emphasis.

His book designs were particularly groundbreaking. For Vladimir Mayakovsky's collection of poems Dlia Golosa (For the Voice, 1923), Lissitzky created a radical design intended for performance reading. He used bold typography, colour-coding, and abstract symbols, integrating them with the text in a dynamic interplay. Most notably, he designed an innovative thumb index system using visual cues, allowing readers to quickly locate specific poems – a functionalist approach typical of Constructivism.

He applied similar principles to posters, journals, and exhibition catalogues. His designs often featured strong diagonal axes, contrasts in scale, photomontage elements, and a limited but impactful colour palette (frequently red, black, and white). He understood graphic design as a powerful tool for communication and propaganda, capable of capturing attention and conveying messages with immediacy and force. His work laid much of the groundwork for modern graphic design practices.

Photography and the Power of the Lens

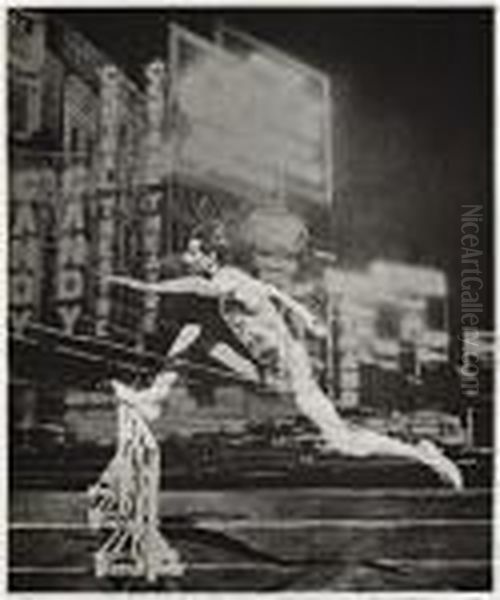

Parallel to his graphic work, Lissitzky explored the possibilities of photography and photomontage with characteristic inventiveness. He saw the camera not just as a tool for documenting reality but as a means of constructing new visual experiences. He experimented with unconventional camera angles (worm's-eye and bird's-eye views), multiple exposures, photograms (cameraless photographic images made by placing objects directly onto photosensitive paper), and photomontage (combining different photographic images).

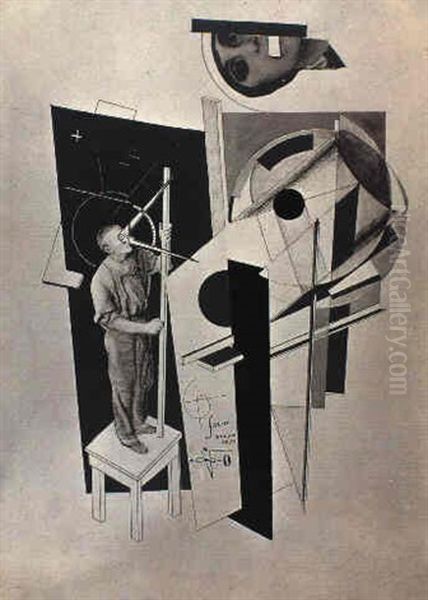

His Self-Portrait (The Constructor) from 1924 is one of his most famous photographic works. It shows his hand superimposed over a portrait of his head, holding a compass against graph paper, with the letters XYZ nearby. This complex image presents the artist as a technician, an engineer of form, blending intellectual conception (head), manual execution (hand), and the tools of design (compass, graph paper, geometric coordinates). It encapsulates the Constructivist ideal of the artist as a builder.

Another notable work, Runner in the City (1926), uses photomontage to create a dynamic image of urban motion and modernity. These photographic experiments were often integrated into his graphic design work, further blurring the lines between disciplines and demonstrating his commitment to using modern technology in service of art and communication. His explorations significantly contributed to the "New Vision" photography movement associated with figures like Moholy-Nagy.

Architectural Visions: Proun Spaces and Cloud-Irons

Although trained as an architect, few of Lissitzky's architectural designs were realized. However, his conceptual work in this field was highly influential. The Proun concept inherently contained architectural implications, exploring space, volume, and structure. He extended this into designs for Prounenraum (Proun Rooms) – immersive exhibition environments where abstract geometric forms extended off the walls and into the viewer's space, breaking down the traditional separation between artwork and observer. He created such a room for the Grosse Berliner Kunstausstellung (Great Berlin Art Exhibition) in 1923.

His most ambitious architectural proposal was the Wolkenbügel (Cloud-Iron or Sky-Hook), designed in the mid-1920s with architect Emil Roth. These were designs for horizontal skyscrapers, massive structures raised on pylons above major intersections in Moscow. Intended as administrative buildings for Soviet ministries, they represented a radical rethinking of urban space and high-rise construction, prioritizing horizontal expansion over vertical ascent. Though never built, the Wolkenbügel designs remain potent symbols of Constructivist utopian ambition and architectural innovation.

Lissitzky also excelled in exhibition design, treating the entire exhibition space as a unified communicative environment. His design for the Soviet pavilion at the International Press Exhibition ("Pressa") in Cologne in 1928 was a triumph. He created a dynamic, multi-sensory experience incorporating large-scale photomontages, moving elements, and innovative display techniques to showcase Soviet achievements in print media. This work cemented his reputation as a master of spatial design and visual communication on a grand scale.

Return to the USSR and Later Years

In 1925, Lissitzky returned to the Soviet Union, partly due to his ongoing battle with tuberculosis, which required treatment. He settled in Moscow and continued to work prolifically, primarily in graphic design, exhibition design, and propaganda. He became one of the leading designers for state-sponsored publications and projects.

A major undertaking was his design work for the lavish propaganda magazine SSSR na Stroike (USSR in Construction), launched in 1930. Published in multiple languages, the magazine used sophisticated photography, photomontage, and layout design – heavily influenced by Lissitzky – to project an image of a dynamic, modernizing Soviet state to both domestic and international audiences. He designed numerous issues, covers, and spreads, often collaborating with leading photographers like Max Penson.

As the political climate in the Soviet Union shifted towards Stalinism and the doctrine of Socialist Realism gained dominance in the arts, the space for avant-garde experimentation narrowed. While Lissitzky adapted his style to meet the demands of state commissions, his underlying principles of clarity, dynamism, and the integration of form and function remained evident. He continued designing posters, including powerful works during World War II, such as the 1941 poster "Davaite pobolshe tankov!" (Let's Have More Tanks!).

Despite his declining health, Lissitzky remained active until the end. His lifelong struggle with tuberculosis finally overcame him, and he died in Moscow on December 30, 1941, at the age of 51. Even on his deathbed, he was reportedly working on a propaganda poster rallying the Soviet people against Nazi Germany.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

El Lissitzky's influence on the trajectory of modern art and design is immense and multifaceted. As a key figure in Suprematism and Constructivism, he helped define the visual language and theoretical underpinnings of the Russian avant-garde. His Proun concept remains a seminal exploration of the intersection between painting and architecture.

His role as a cultural bridge between Russia and the West was crucial. Through his activities in Berlin, his publications, and his interactions with artists like Schwitters, van Doesburg, Moholy-Nagy, and Arp, he disseminated avant-garde ideas across Europe, significantly impacting movements like De Stijl and the Bauhaus. His innovations in typography, graphic design, and photomontage fundamentally shaped the field of visual communication, influencing generations of designers. Pioneers like Jan Tschichold acknowledged his impact on the "New Typography."

His approach to exhibition design, treating space as an active medium, transformed the practice and continues to inform contemporary museum and exhibition strategies. While few of his architectural projects were built, his conceptual designs like the Wolkenbügel remain important examples of utopian modernist thinking. Furthermore, his theoretical writings, exploring the relationship between art, technology, and society, contributed to the intellectual discourse of modernism. Figures like Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian, though pursuing different paths within abstraction, were part of the broader network of European modernists with whom Lissitzky's ideas intersected.

Conclusion: The Constructor of a New Vision

El Lissitzky was more than an artist; he was a visionary constructor. He saw art not as an end in itself but as a means to build a new world, a new perception, a new social reality. His relentless experimentation across disciplines – from painting and architecture to typography and photography – was driven by a profound belief in the transformative power of design. He navigated the complex currents of revolution, cultural exchange, and political ideology, consistently producing work that was formally innovative and conceptually rich.

His legacy lies not only in iconic works like Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge or the Proun series but also in his holistic approach to visual culture. He demonstrated how abstract principles could be applied to practical problems of communication and construction, how art could engage directly with technology and society. El Lissitzky remains a pivotal figure whose work bridged art forms, cultures, and ideologies, forever shaping our understanding of modernism and the potential of design to envision and enact change.