Ohara Koson, a name that resonates with connoisseurs of Japanese woodblock prints, stands as one of the most significant artists of the Shin-hanga (New Prints) movement. His prolific output, primarily focused on kachō-e (bird-and-flower pictures), captured the delicate beauty of the natural world with remarkable sensitivity and technical skill. Though he used several names throughout his career, including Shoson and Hoson, the artist born Ohara Matao left an indelible mark on early 20th-century Japanese art, particularly through his works that found immense popularity in the West.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

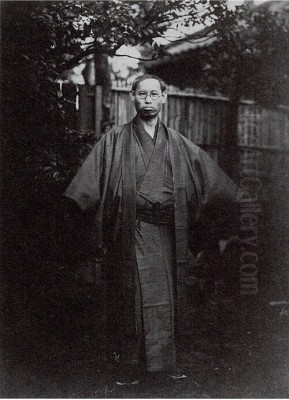

Ohara Matao was born on February 9, 1877, in Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture, a region known for its rich artistic heritage. His early artistic inclinations led him to the Ishikawa Prefecture Technical School around 1889, where he studied painting and design until approximately 1893. This formal training provided him with a solid foundation in the principles of Japanese art.

A pivotal moment in his development came when he moved to Tokyo and became a student of Suzuki Kason (1860-1919). Kason was a respected painter of the Shijō school, known for his own exquisite kachō-e and his involvement in both traditional painting and print design. Under Kason's tutelage, Matao honed his skills in depicting flora and fauna with accuracy and artistic grace. It was also a common practice for students to adopt a part of their master's name, and in a gesture of respect, Ohara Matao would later adopt the art name "Koson," the "son" character likely derived from his teacher's name. This master-apprentice relationship was crucial in shaping Koson's artistic trajectory and his deep understanding of natural subjects.

The Transition to Printmaking and Early Career

Initially, Ohara Koson pursued a career as a painter, following in the footsteps of his teacher Suzuki Kason. However, the art world in Japan was undergoing significant changes during the Meiji era (1868-1912). Traditional art forms like ukiyo-e were facing a decline in popularity, partly due to the advent of photography and new printing technologies. Despite this, there was a burgeoning interest in Japanese art in the West, fueled by Japonisme.

Koson's foray into woodblock print design began in the early 1900s. Some of his earliest known prints were triptychs depicting scenes from the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), published by Daikokuya (Matsuki Heikichi). These works, while demonstrating his skill, were typical of the patriotic imagery popular at the time and differed significantly from the nature subjects that would later define his career. Artists like Kobayashi Kiyochika and Ogata Gekkō also produced notable war prints during this period.

It was perhaps the influence of Ernest Fenollosa, an American scholar and passionate advocate for Japanese art, that encouraged Koson to focus on traditional subjects for the export market. Fenollosa, along with Okakura Tenshin, was instrumental in promoting Japanese arts and crafts. Fenollosa recognized the appeal of kachō-e to Western audiences and likely saw Koson's potential in this genre. Koson also taught at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (now Tokyo University of the Arts), where Fenollosa had been a key figure.

The Koson, Shoson, and Hoson Periods

Throughout his career, Ohara Koson used different art names, or gō, which can sometimes cause confusion but often signifies different periods or affiliations with publishers. His earliest prints, primarily those published by Daikokuya and Kokkeidō (Akiyama Buemon) up until around 1912, were signed "Koson." These early kachō-e prints, often in smaller formats like tanzaku (pillar prints) or kakejiku-e (prints designed to be mounted as hanging scrolls), already showcased his talent for capturing the essence of birds and flowers with lifelike detail and atmospheric settings.

After a period of focusing on painting, Koson re-emerged in the print world around 1926, this time primarily associated with the influential publisher Watanabe Shōzaburō (1885-1962). Watanabe was the driving force behind the Shin-hanga movement, which aimed to revitalize traditional ukiyo-e by incorporating Western aesthetics like realism and perspective while maintaining the collaborative "quartet" system of artist, carver, printer, and publisher. For prints published by Watanabe, Koson adopted the name "Shoson." These Shoson prints are perhaps his most famous and widely collected works, characterized by their exquisite carving, sophisticated printing techniques, and often more complex compositions.

Later in his career, he also used the name "Hoson," particularly for works published by Kawaguchi & Sakai. However, the bulk of his most celebrated bird-and-flower prints bear the Shoson signature. It's important to note that these name changes did not signify a drastic shift in his core artistic style, which remained consistently focused on the naturalistic and poetic depiction of nature, but rather reflected his working relationships with different publishing houses.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Techniques

Ohara Koson's art is almost exclusively dedicated to kachō-e. His deep appreciation for nature is evident in every print. He possessed an uncanny ability to capture not just the physical likeness of birds, animals, and plants, but also their inherent character and the fleeting moments of their existence. His subjects are often depicted in quiet, contemplative scenes: a kingfisher diving for fish, crows perched on a snow-covered branch, herons wading in a misty marsh, or geese flying across a full moon.

His style is marked by several key characteristics:

1. Naturalism and Detail: Koson's depictions are highly realistic, based on careful observation. Feathers are rendered with individual precision, the textures of bark and leaves are palpable, and the anatomy of animals is accurate. This realism appealed greatly to Western tastes, which were accustomed to academic naturalism.

2. Atmospheric Effects: He was a master at conveying atmosphere – the stillness of a snowy night, the dampness of a rainy day, the ethereal quality of mist, or the golden light of dawn. Techniques like bokashi (color gradation) were expertly employed to create these effects.

3. Compositional Skill: Koson's compositions are often dynamic yet balanced. He frequently used asymmetrical arrangements, a hallmark of Japanese art, and employed empty space (ma) effectively to create a sense of depth and focus attention on the subject. The vertical format of tanzaku prints was particularly well-suited to his depictions of birds on branches or tall grasses.

4. Subtle Color Palettes: While capable of using vibrant colors, many of Koson's prints feature subtle, harmonious color palettes that enhance the naturalism and poetic mood of the scenes. The use of gofun (powdered seashell) to depict snow added a tactile quality to his winter scenes.

5. Emotional Resonance: Beyond mere representation, Koson's works evoke a sense of tranquility, melancholy, or the quiet drama of nature. There is a poetic sensibility that infuses his art, inviting contemplation.

He drew inspiration from the long tradition of bird-and-flower painting in East Asia, which includes masters like the Chinese Emperor Huizong of the Song Dynasty, and Japanese masters such as Sesshū Tōyō and Maruyama Ōkyo. Within the ukiyo-e tradition, artists like Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Hiroshige also produced notable kachō-e, though Koson's approach within the Shin-hanga framework brought a new level of refined naturalism.

Representative Works

Ohara Koson produced an estimated 500 woodblock prints during his lifetime. Among his most celebrated and representative works are:

"Cherry Blossom with Swallows": This iconic image captures the dynamism of swallows in flight against a backdrop of delicate cherry blossoms. The composition is lively, and the rendering of both the birds and flowers is exquisite, embodying the fleeting beauty of spring.

"Sparrow on Bamboo in Snow": A common theme for Koson, this subject showcases his ability to depict the resilience of nature. The sparrow, often fluffed up against the cold, contrasts with the stark bamboo and the soft, textured snow, often rendered with gofun.

"Parrot on Zelkova Tree" (or similar titles with parrots/cockatoos): These prints, often featuring brightly colored exotic birds, were particularly popular with Western collectors. The vibrant plumage of the bird against the more subdued tones of the tree and background creates a striking visual impact.

"Geese Flying Across a Full Moon": A classic motif in Japanese art, Koson’s interpretations are notable for their atmospheric depth and the graceful depiction of the geese in formation. The moon often serves as a powerful focal point, its light casting a serene glow.

"Kingfisher with Lotus": The kingfisher, a recurring subject, is often shown in a moment of intense focus, either perched or diving. The combination of the iridescent bird with the elegant lotus flowers creates a scene of natural harmony.

"Crows on a Snowy Branch": Koson masterfully used the contrast of the black crows against the white snow and grey sky to create stark, powerful, and somewhat melancholic images. The texture of the snow and the crows' feathers are rendered with great skill.

These examples highlight Koson's consistent themes and his ability to imbue each scene with a unique mood and meticulous detail. His works often feature a single bird or a small group, allowing for an intimate focus on the subject within its natural habitat.

The Shin-Hanga Movement and Koson's Role

Ohara Koson is considered a leading figure of the Shin-hanga (New Prints) movement. This movement, spearheaded by the publisher Watanabe Shōzaburō from around 1915, sought to revive the traditional ukiyo-e woodblock printing process, which had declined with the rise of modern printing methods. Shin-hanga artists aimed to create high-quality prints that appealed to both domestic and, crucially, international markets.

The Shin-hanga philosophy involved a collaborative effort, often referred to as the "Watanabe quartet":

1. The Artist (e.g., Koson/Shoson): Created the original design or painting.

2. The Carver: Meticulously carved the multiple woodblocks, one for each color and one for the key lines.

3. The Printer: Applied the colors to the blocks and hand-printed the image onto paper, often using sophisticated techniques like bokashi (color gradation) and karazuri (embossing).

4. The Publisher (e.g., Watanabe): Coordinated the entire process, financed the production, and marketed the prints.

Watanabe was a visionary who understood the Western appetite for romanticized and technically superb depictions of Japan. He recruited talented artists like Kawase Hasui, known for his evocative landscapes; Hiroshi Yoshida, another landscape artist who later took control of his own printing; Itō Shinsui, famous for his bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women); Hashiguchi Goyō, whose brief career produced some of the most exquisite bijin-ga of the era; Tsuchiya Koitsu, who specialized in landscapes with dramatic light effects; and Natori Shunsen and Torii Kotondo, who excelled in actor prints and bijin-ga respectively.

Koson (as Shoson) fit perfectly into Watanabe's vision for kachō-e. His designs were ideally suited for the meticulous carving and printing that characterized Shin-hanga. The resulting prints were of exceptional quality, with rich colors, subtle gradations, and fine details that surpassed much of the later, mass-produced ukiyo-e. While Shin-hanga artists incorporated elements of Western realism, such as perspective and naturalistic light, they retained traditional Japanese aesthetics in terms of composition, subject matter, and poetic sensibility. This fusion proved highly successful, especially in the American and European markets.

It is important to distinguish Shin-hanga from the concurrent Sōsaku-hanga (Creative Prints) movement, where artists like Onchi Kōshirō and Hiratsuka Un'ichi advocated for the artist's complete control over the entire process – designing, carving, and printing their own work, emphasizing self-expression over traditional craftsmanship. Koson remained firmly within the collaborative Shin-hanga tradition.

International Recognition and Ernest Fenollosa's Influence

While Ohara Koson's prints were produced in Japan, a significant portion of his output, especially those made under the name Shoson for Watanabe, was intended for export. His work gained considerable popularity in the United States and Europe during the early to mid-20th century. The delicate beauty, technical perfection, and accessible subject matter of his kachō-e resonated deeply with Western collectors.

The groundwork for this international appreciation was laid by figures like Ernest Fenollosa. As mentioned earlier, Fenollosa, an American professor of philosophy and political economy at Tokyo Imperial University, became a fervent admirer and scholar of Japanese art. He, along with William Sturgis Bigelow, amassed significant collections that later formed the core of the Japanese art collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Fenollosa's advocacy and his connections likely played a role in encouraging artists like Koson to produce works that would appeal to Western tastes, emphasizing traditional themes and high craftsmanship.

Koson's teaching position at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (Tokyo Bijutsu Gakkō), where Fenollosa and Okakura Tenshin had been influential, further placed him within a circle that was conscious of the international art scene. The success of Koson's prints abroad meant that for many years, he was better known and more highly collected in the West than in Japan itself, a fate shared by several other Shin-hanga artists. His prints became staples in Western collections of Japanese art, admired for their decorative qualities and their sensitive portrayal of the natural world.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Ohara Koson worked during a dynamic period in Japanese art. His primary influence was undoubtedly his teacher, Suzuki Kason, whose own kachō-e paintings and prints provided a direct model. Kason himself was part of a generation of artists adapting to the Meiji era's changes, working in both traditional Nihonga painting styles and designing for prints and other media.

Within the Shin-hanga movement, Koson was a specialist in kachō-e, while his contemporaries focused on other genres. Kawase Hasui and Hiroshi Yoshida were the preeminent landscape artists, capturing the beauty of Japan's scenery with atmospheric depth and realism. Itō Shinsui, Hashiguchi Goyō, Torii Kotondo, and Shima Seien excelled in bijin-ga, updating the traditional theme of beautiful women with modern sensibilities. Natori Shunsen and Yamamura Kōka (Toyonari) were known for their powerful actor portraits (yakusha-e).

While their subject matter differed, these artists shared a commitment to the Shin-hanga ideals of high-quality craftsmanship and a fusion of Japanese tradition with Western artistic elements. They all benefited from the entrepreneurial spirit of publishers like Watanabe Shōzaburō, who cultivated their talents and found markets for their work. The collaborative nature of Shin-hanga meant that the skills of the carvers and printers were also paramount to the success of the final artwork. For instance, the carvers employed by Watanabe, such as Yamagishi Kazue, and printers like Ono Gintarō, were masters in their own right.

Koson's focus on nature also connects him to a broader tradition of Japanese art that emphasizes harmony with the natural world, seen in the works of earlier Rinpa school artists like Ogata Kōrin or the Shijō school painters like Matsumura Goshun.

Anecdotes and Artistic Identity

One of the most notable aspects of Koson's career is his use of multiple names – Koson, Shoson, and Hoson. While not uncommon for Japanese artists to change names to mark new phases or affiliations, it has sometimes led to his work being cataloged under different identities. However, art historians now firmly establish that these names all refer to Ohara Matao. The "Koson" signature is generally associated with his early works for publishers like Daikokuya and Kokkeidō. The "Shoson" signature is predominantly found on prints published by Watanabe Shōzaburō from the mid-1920s onwards and represents the peak of his kachō-e production. The "Hoson" signature appears on works for other publishers like Kawaguchi & Sakai.

His initial foray into war prints during the Russo-Japanese War is an interesting, though brief, chapter in his career, showing an artist responding to contemporary events before finding his true calling in the timeless beauty of nature. The shift from primarily being a painter to a prolific print designer also highlights the changing economic realities and artistic opportunities of the time, particularly the demand from the Western market for high-quality woodblock prints.

Despite his international success, Koson, like many Shin-hanga artists, remained relatively uncelebrated in Japan during his lifetime, where the art world's focus was often on oil painting or more avant-garde movements. The appreciation for Shin-hanga within Japan grew significantly in the postwar period and beyond, as the nation re-evaluated its own artistic heritage.

The Second World War inevitably impacted artistic production in Japan due to material shortages and a shift in national priorities. While Koson continued to work, the output of Shin-hanga prints, in general, declined during this period. He passed away on January 4, 1945, just before the end of the war, leaving behind a rich legacy of hundreds of exquisite designs.

Later Career and Enduring Legacy

Ohara Koson's career spanned several decades, from the late Meiji period through the Taishō and into the early Shōwa period. His most productive and arguably most refined period as a print designer was his association with Watanabe Shōzaburō under the name Shoson, beginning in 1926. During this time, he produced a large number of the bird-and-flower prints that are now his most recognized and sought-after works.

Even during the challenging war years, he continued to create, though the circumstances were difficult. His dedication to his art, specifically the meticulous observation and poetic rendering of nature, remained constant throughout his life.

Today, Ohara Koson is recognized as one of the foremost kachō-e artists of the 20th century and a key figure in the Shin-hanga movement. His prints are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the British Museum, London; and the Tokyo National Museum. They are also highly prized by private collectors.

His legacy lies in his ability to capture the subtle beauty and intimate moments of the natural world with unparalleled technical skill and artistic sensitivity. He successfully blended traditional Japanese aesthetics with a modern, naturalistic approach, creating works that possess a timeless appeal. His prints continue to enchant viewers with their delicate charm, serene beauty, and the profound sense of connection to nature they evoke. Artists like Imao Keinen, who was slightly earlier, also specialized in kacho-ga, and Koson's work can be seen as a continuation and refinement of this tradition within the Shin-hanga context.

Conclusion

Ohara Koson (Matao), through his various artistic personas of Koson, Shoson, and Hoson, carved a unique niche in the world of Japanese woodblock prints. As a student of Suzuki Kason and a prominent artist within Watanabe Shōzaburō's Shin-hanga circle, he elevated the genre of kachō-e to new heights of technical perfection and poetic expression. His keen eye for detail, mastery of composition, and profound empathy for his natural subjects resulted in a body of work that transcended mere decoration, offering intimate glimpses into the delicate balance and beauty of the flora and fauna of Japan. While he may have been more celebrated abroad than at home during his lifetime, his enduring legacy as a master of bird-and-flower prints is now firmly established, his art continuing to inspire and captivate audiences globally.