Orazio Samacchini (1532-1577) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant artistic landscape of sixteenth-century Italy. Born in Bologna, a city with a rich artistic heritage, Samacchini navigated the complex stylistic currents of his time, moving from the lingering classicism of the High Renaissance towards the more stylized and expressive forms of Mannerism. His career, though relatively short, saw him undertake important commissions in his native Bologna, as well as in Rome and other Italian cities, leaving behind a body of work that reflects both his technical skill and his engagement with the leading artistic trends of the era. His oeuvre primarily consists of religious scenes, altarpieces, and extensive fresco decorations, demonstrating a versatility in both medium and subject matter.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Bologna

Born in 1532, Orazio Samacchini's early artistic education unfolded in Bologna, a city that was a crucible of artistic innovation, particularly within the Emilia-Romagna region. The artistic environment was rich with the legacies of earlier masters and the dynamic presence of contemporary painters. Among his earliest and most formative influences was Pellegrino Tibaldi (1527-1596), a highly original artist whose own work bridged High Renaissance ideals with emergent Mannerist tendencies. Tibaldi's powerful, often Michelangelesque figures and complex spatial arrangements would have provided a compelling model for the young Samacchini.

Beyond Tibaldi, Samacchini's initial style also shows an assimilation of influences from other local Bolognese and Emilian painters. These include Prospero Fontana (1512-1597), with whom he would later collaborate, and who was himself a significant figure in the Bolognese school, known for his decorative work and his role as a teacher. The influence of earlier Emilian masters like Innocenzo da Imola (c. 1490-c. 1550) and Bartolomeo Ramenghi, known as Bagnacavallo (1484-1542), can also be discerned. These artists represented a more traditional, Raphaelesque classicism, characterized by clarity of form, balanced compositions, and a gentle piety. Samacchini's early works, such as the Marriage of the Virgin (circa 1555-1560), reflect this grounding, displaying a preference for clear outlines, pure, luminous colors, and a certain compositional simplicity reminiscent of Raphael Sanzio's (1483-1520) harmonious ideals.

This period was crucial for developing his technical facility. The Bolognese workshops emphasized strong draftsmanship and a solid understanding of traditional painting techniques. Samacchini absorbed these lessons, demonstrating an early command of anatomy and perspective, which would serve as a foundation for his later, more complex undertakings. His ability to synthesize these varied local influences marked him as a promising talent within the competitive Bolognese art scene.

The Roman Sojourn: Exposure to High Renaissance and Mannerist Grandeur

A pivotal moment in Samacchini's artistic development occurred in 1563 when he traveled to Rome. This journey was not uncommon for ambitious artists of the period, as Rome was the undisputed center of the art world, offering unparalleled opportunities to study the masterpieces of antiquity and the High Renaissance, as well as to engage with the most current artistic movements. In Rome, Samacchini was involved in prestigious decorative projects under the patronage of Pope Pius IV. He contributed to the decorations of the Vatican Belvedere Palace and the Sala Regia (Royal Hall), a grand ceremonial space within the Apostolic Palace.

Working in the Vatican placed Samacchini in direct contact with the monumental legacy of artists like Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) and Raphael. The power of Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling and Last Judgment, with their dynamic figures and dramatic intensity, left an indelible mark on countless artists, Samacchini included. Raphael's Stanze, with their classical grace and narrative clarity, also offered profound lessons. Furthermore, Rome was a hub for Mannerism, and Samacchini encountered the work of its leading proponents. He is known to have collaborated or worked alongside prominent Mannerists such as Taddeo Zuccari (1529-1566) and Federico Zuccari (c. 1540/1541-1609), as well as Francesco Salviati (1510-1563), whose sophisticated, elegant, and often intricate style was highly influential.

This Roman experience profoundly impacted Samacchini's art. His compositions became more complex and dynamic, his figures more muscular and imbued with a greater sense of movement, often arranged in elaborate, sometimes crowded, spatial constructions. The clear, bright palette of his earlier Bolognese period began to incorporate a wider range of hues and more dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, characteristic of Roman Mannerism. The experience of working on large-scale fresco decorations in the Vatican also honed his skills in managing complex narrative scenes and integrating figures within architectural settings. Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), the renowned artist and art historian, noted Samacchini's work in Rome, praising his abilities, which suggests that Samacchini made a favorable impression in the highly competitive Roman environment.

Return to Bologna and Mature Career

Upon his return to Bologna, Orazio Samacchini emerged as a mature and respected artist, his style enriched and transformed by his Roman experiences. He successfully integrated the grandeur and complexity of Roman Mannerism with the more grounded traditions of his native Bolognese school. This synthesis resulted in a distinctive personal style that was both sophisticated and accessible, making him a sought-after painter for important civic and ecclesiastical commissions.

He became a prominent member of the Bolognese artistic community, working alongside other leading local painters such as Lorenzo Sabatini (c. 1530-1576), who was also active in Rome and shared some stylistic affinities with Samacchini. Together, they, along with Prospero Fontana and others, contributed to defining the character of Bolognese painting in the latter half of the sixteenth century, a period that would lay the groundwork for the later innovations of the Carracci family – Annibale (1560-1609), Agostino (1557-1602), and Ludovico (1555-1619) – who would usher in the Baroque era.

Samacchini's mature works demonstrate a confident handling of complex compositions, often featuring numerous figures in dynamic poses. His draftsmanship remained strong, but his figures often took on the elongated proportions and graceful contortions characteristic of Mannerism. His color palette became richer and more varied, capable of conveying both solemnity and vibrancy. He was particularly adept at fresco painting, a demanding medium that required speed and precision, and he undertook several large-scale decorative cycles in Bolognese churches and palaces.

Major Works and Fresco Cycles

Orazio Samacchini's reputation rests significantly on his extensive fresco cycles and important altarpieces. One of his notable commissions was for the Parma Cathedral, where he painted frescoes in the north transept, including a depiction of Moses Striking the Rock (circa 1570-1577). This work, with its crowded composition and energetically rendered figures, showcases his mature Mannerist style and his ability to handle large narrative scenes. The influence of Michelangelo is palpable in the muscularity of the figures, while the overall decorative sensibility aligns with contemporary Mannerist practice.

In Città di Castello, Samacchini executed frescoes in the Palazzo Vitelli alla Cannoniera, a significant commission that further attests to his growing reputation beyond Bologna. The subjects included religious figures such as Saint Giles, Saint Castro, Saint James Major, Santa Maria Maggiore, and Saint Gregory the Great. These works would have allowed him to display his skills in figure painting and narrative composition within an architectural framework.

Back in Bologna, he was active in numerous churches. His Trinity in the church of Santa Maria dei Servi (or perhaps another church, as sources sometimes vary) became a particularly influential work. Its composition was disseminated through prints, reaching a wider audience and even influencing artists in other regions, including Spain. This demonstrates the reach of his designs beyond the immediate context of the original commission. Another significant altarpiece is the Annunciation in Forlì, which would have showcased his ability to convey religious devotion through elegant figures and harmonious, if often complex, compositions.

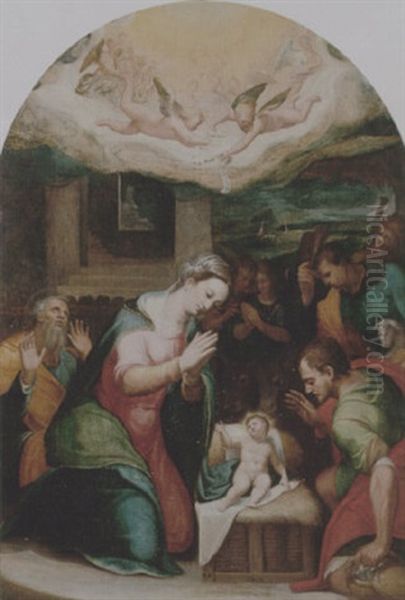

The Assumption of the Virgin (circa 1556), an earlier panel painting, is often cited as representative of his initial phase, characterized by its clearer lines and more restrained palette, showing the influence of the Raphaelesque tradition prevalent in Bologna before his Roman sojourn. Comparing this with his later works reveals the significant evolution of his style. His Mystical Marriage of St. Catherine is another example of his panel paintings, likely demonstrating a rich use of color and a sophisticated arrangement of figures, blending devotional content with Mannerist elegance. He also contributed to the decoration of the San Giacomo Maggiore in Bologna, a major church that housed works by many prominent Bolognese artists.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Influences

Orazio Samacchini's artistic style is best understood as a sophisticated fusion of various influences, characteristic of the eclectic nature of much Mannerist art. His grounding in the Bolognese tradition provided him with a solid foundation in draftsmanship and a certain Emilian grace, inherited from masters like Correggio (Antonio Allegri da Correggio, c. 1489-1534) and Parmigianino (Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, 1503-1540), whose elegant and sensuous styles had a lasting impact on the region.

From Pellegrino Tibaldi, he absorbed a tendency towards robust, muscular figures and dynamic compositions. His Roman experience then layered upon this foundation the grandeur of Michelangelo, evident in the heroic scale and anatomical emphasis of many of his figures, and the sophisticated elegance of Roman Mannerists like Francesco Salviati and the Zuccari brothers. Salviati's influence can be seen in the intricate decorative patterns, elongated figures, and complex allegorical or narrative content that Samacchini sometimes employed. Federico Zuccari's more academic and clear form of Mannerism also seems to have resonated with Samacchini in his later works.

His compositions are often characterized by a careful, sometimes crowded, arrangement of figures. While he could achieve a sense of monumentality, there is also a decorative quality to his work, with attention paid to flowing draperies and graceful poses. His color palette evolved from the clearer, brighter tones of his youth to a richer, more varied, and sometimes more intense range of colors typical of Mannerism. He was skilled in creating a sense of movement and energy, though occasionally, like many Mannerists, this could lead to figures in somewhat artificial or contorted poses.

Despite the evident influences, Samacchini was not merely an imitator. He forged a personal style that was well-suited to the devotional and decorative needs of his patrons. His work often possesses a refined elegance and a technical proficiency that made him a respected figure in his time. He navigated the transition from High Renaissance classicism to the more subjective and stylized world of Mannerism, reflecting the broader artistic shifts of the sixteenth century.

Critical Reception and Legacy

Historically, Orazio Samacchini has been recognized as an important exponent of the Bolognese school of the late sixteenth century. Giorgio Vasari, in his "Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects," acknowledged Samacchini's talent, particularly praising his work after his Roman experience, which Vasari felt had significantly improved his style. This contemporary endorsement from such an influential figure is significant.

However, like many artists who worked in a transitional period or whose style was a synthesis of various influences, Samacchini has also faced criticism. Some art historians have pointed to a degree of derivativeness in his work, suggesting that he sometimes relied heavily on the models of greater masters, particularly Michelangelo and Raphael, or his more immediate mentor, Tibaldi. His early works, while competent, are sometimes seen as closely following the patterns set by his Bolognese predecessors.

Despite these criticisms, Samacchini's contribution lies in his ability to absorb and adapt prevailing artistic currents to create works that were both accomplished and well-received in his time. He played a role in disseminating Roman Mannerist ideas in Bologna, contributing to the city's vibrant artistic culture. His influence extended through his pupils and through the dissemination of his designs, such as the aforementioned Trinity, via engravings. This practice of printmaking allowed his compositions to reach artists and audiences far beyond the immediate location of his paintings, contributing to the spread of Italian artistic ideas across Europe.

His works, particularly his frescoes, demonstrate a high level of technical skill and an ability to manage large-scale, complex decorative programs. While perhaps not an innovator on the scale of Michelangelo or Raphael, or the later Carracci, Samacchini was a highly proficient and productive artist who successfully met the demands of his patrons and contributed significantly to the artistic fabric of Bologna and other centers where he worked. His art reflects the sophisticated, often intellectual, and highly stylized tastes of the Mannerist period.

The existence of Orazio Samacchini is well-documented. Born in 1532, he died relatively young in Bologna in 1577, at the age of 45. His documented commissions, contemporary accounts like Vasari's, and the survival of a significant body of his work firmly establish his historical presence and his role in sixteenth-century Italian art.

Conclusion: Samacchini's Place in Art History

Orazio Samacchini was a quintessential artist of his time, a product of the rich artistic environment of Bologna and the transformative power of Rome. He skillfully navigated the stylistic complexities of the late Renaissance and Mannerism, creating a body of work characterized by technical competence, compositional sophistication, and an elegant, if sometimes derivative, figural style. His engagement with masters such as Pellegrino Tibaldi, Michelangelo, Raphael, Francesco Salviati, and the Zuccari brothers shaped his artistic vision, allowing him to forge a successful career as a painter of altarpieces and large-scale fresco decorations.

While he may not be as widely known today as some of his more revolutionary contemporaries or successors, Samacchini played an important role in the artistic life of Bologna and contributed to the broader currents of Italian Mannerism. His ability to synthesize diverse influences and adapt them to the needs of his patrons ensured his success during his lifetime. His works remain as testaments to a skilled artist working at a high level within the established artistic conventions of his era, contributing to the rich tapestry of Italian art in the dynamic sixteenth century. His legacy is that of a talented practitioner who helped to define the visual culture of his region during a period of significant artistic transition.