Owen Jones (1809-1874) stands as a monumental figure in the landscape of 19th-century design. A British architect, designer, and theorist of Welsh descent, born in London, Jones was a pivotal force in the evolution of modern design principles, particularly in the realms of decorative arts, flat pattern, and color theory. His meticulous research, influential publications, and practical design work left an indelible mark on Victorian aesthetics and laid a foundational framework for subsequent generations of designers. His quest for universal principles of design, derived from a global study of ornament, challenged the prevailing historicist pastiches of his time and advocated for a more rational, harmonious, and appropriate application of decoration.

Early Life, Education, and Formative Travels

Born in London on February 15, 1809, Owen Jones was the son of Owen Jones Snr., a noted Welsh antiquarian and furrier. This background likely instilled in him an early appreciation for history, craftsmanship, and cultural artifacts. His formal architectural training began with an apprenticeship under the architect Lewis Vulliamy, which lasted for six years. During this period, he also studied at the Royal Academy Schools, further honing his skills and theoretical understanding of architecture. Vulliamy's office would have exposed him to the prevailing architectural styles and practices of the day, including Neoclassicism and the burgeoning Gothic Revival.

However, it was his extensive travels between 1832 and 1834 that proved most transformative for Jones's artistic vision. Like many aspiring architects and artists of his era, he embarked on a form of Grand Tour, though his itinerary extended beyond the classical sites of Italy and Greece. He journeyed to Egypt, Turkey, and, most significantly, to Spain. It was in Granada, at the Alhambra Palace, that Jones encountered a system of ornament that would profoundly shape his life's work. The intricate geometric patterns, the sophisticated use of color, and the abstract, non-representational nature of Islamic design captivated him.

The Revelation of the Alhambra

The Alhambra, a 13th-century Moorish palace and fortress, presented Jones with a design language radically different from the Western classical tradition. He was struck by its flat, stylized ornamentation, its brilliant polychromy, and the mathematical precision underpinning its seemingly endless variety of patterns. He spent months meticulously studying and drawing the palace's details, often working under challenging conditions.

During his time in Granada, Jones collaborated with the French architect Jules Goury. Together, they undertook an exhaustive survey of the Alhambra's decorative schemes. Tragically, Goury succumbed to cholera in 1834, leaving Jones to complete their ambitious project. The result was the monumental publication, Plans, Elevations, Sections, and Details of the Alhambra, issued in parts between 1836 and 1845. This lavishly illustrated work, utilizing the then-new technology of chromolithography, was a landmark in architectural publishing and introduced the splendors of Islamic design to a wider European audience. It set new standards for color printing and established Jones as a leading authority on non-Western ornament. The Alhambra studies were crucial in developing his theories on the appropriate use of color and the importance of conventionalized, rather than naturalistic, forms in decoration.

The Great Exhibition and the Crystal Palace Controversy

Owen Jones's expertise in color and decoration brought him a prominent role in one of the 19th century's most iconic events: the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, held in London in 1851. He was appointed as one of the Superintendents of Works for the exhibition building, Joseph Paxton's revolutionary iron and glass structure, the Crystal Palace. Jones was specifically tasked with the interior decoration scheme.

Drawing on his studies of ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Moorish polychromy, Jones proposed a bold and controversial color scheme for the Crystal Palace's interior. He advocated for the primary colors—red, yellow, and blue—to be applied to the structural ironwork in carefully determined proportions. His rationale was that these colors, when used in their "true" or "primitive" forms and balanced correctly, would create a harmonious and visually coherent space, preventing the vast structure from appearing monotonous or overwhelming. He argued that the colors would also help to define the structure and enhance the perception of distance.

His proposals met with considerable resistance. Many critics and members of the public, accustomed to more subdued or naturalistic color palettes, found his scheme garish or overly simplistic. Figures like John Ruskin, a highly influential art critic, were initially skeptical, though Ruskin later acknowledged some merit in Jones's approach. Despite the outcry, Jones's scheme was largely implemented. The interior of the Crystal Palace, with its vibrant columns and girders, became a defining feature of the exhibition and a talking point for years to come. This project demonstrated Jones's commitment to applying theoretical principles to large-scale practical applications and his willingness to challenge conventional taste.

The Grammar of Ornament: A Magnum Opus

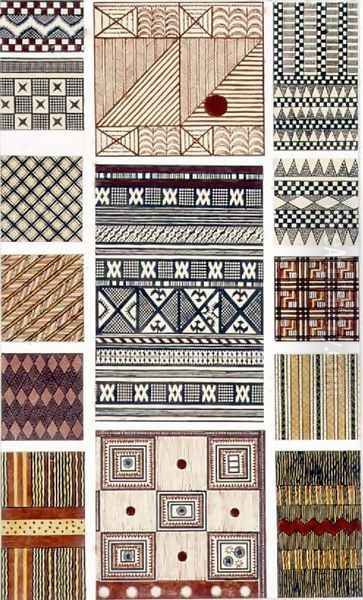

Jones's most enduring legacy is undoubtedly his 1856 publication, The Grammar of Ornament. This encyclopedic volume was the culmination of years of research and a testament to his belief in the universal principles underlying decorative art across diverse cultures and historical periods. The book features 112 folio plates, exquisitely printed using chromolithography, showcasing thousands of ornamental motifs.

The scope of The Grammar of Ornament is vast, encompassing designs from ancient Egypt, Assyria, Greece, Rome, Byzantium, Arabia, Turkey, Persia, India, and China, as well as Celtic, Medieval, Renaissance, Elizabethan, and Italian ornament. Crucially, Jones also included a chapter on "Ornaments of Savage Tribes," demonstrating an early, albeit colonial-era, attempt to recognize the aesthetic value of non-Western indigenous art. Each section is preceded by a descriptive text, and the work concludes with Jones's famous 37 "General Principles in the Arrangement of Form and Colour, in Architecture and the Decorative Arts."

These propositions distilled his core beliefs about design. For instance, Proposition 1 states, "The Decorative Arts arise from, and should properly be attendant upon, Architecture." Proposition 5 asserts, "Construction should be decorated. Decoration should never be purposely constructed." Proposition 8 emphasizes, "All ornament should be based upon a geometrical construction." Proposition 13 famously declares, "Flowers or other natural objects should not be used as ornaments, but conventional representations founded upon them sufficiently suggestive to convey the intended image to the mind, without destroying the unity of the object they are employed to decorate." This advocacy for conventionalization over direct naturalism was a cornerstone of his philosophy.

The Grammar of Ornament became an indispensable sourcebook for designers, architects, and craftspeople. It provided a rich visual vocabulary and a theoretical framework for creating new designs. Its influence can be seen in the work of many subsequent designers, including William Morris and Christopher Dresser, and it remains a valuable reference work to this day. The quality of its chromolithographic plates also set a new benchmark for design publications.

Further Design Work, Theories, and Publications

Beyond his major publications and the Crystal Palace, Owen Jones was involved in various architectural and design projects. He designed interiors, furniture, textiles, wallpapers, and tiles. His commercial work included designs for the firm De La Rue & Co., for whom he created innovative patterns for playing cards, bookbindings, and postage stamps. These smaller-scale works allowed him to explore his principles of flat pattern and color harmony in diverse applications.

One of his notable architectural commissions was St. James's Hall in Piccadilly, London (1858, demolished 1905), a concert hall. While the hall was acoustically successful, its interior decoration, which again employed Jones's characteristic polychromy and Moorish-inspired details, received mixed reviews, with some finding it overly ornate or exotic for its context.

In 1867, Jones published another significant work, Examples of Chinese Ornament. Similar in format to The Grammar of Ornament, this book presented 100 color plates illustrating motifs from Chinese porcelain, cloisonné, and painted enamels. It helped to popularize Chinese design elements in the West and further demonstrated Jones's global perspective on ornament.

Jones's theories continued to evolve and be disseminated through his writings and lectures. He consistently argued for "fitness for purpose" in design, meaning that decoration should be appropriate to the object it adorns and the materials from which it is made. He was a critic of the often-unthinking imitation of historical styles that characterized much Victorian design, advocating instead for the development of a new, modern style rooted in universal principles but responsive to contemporary needs and technologies. His emphasis on flat pattern, as opposed to illusionistic three-dimensional representation in ornament, was a significant departure from prevailing tastes and prefigured later modernist concerns with surface and abstraction.

He also contributed to the discourse on color theory. He believed that primary colors should be used in their pure state, often balanced with secondary and tertiary colors, and that black and white could be used to define and enhance color schemes. His ideas on color harmony were derived from his observations of historical precedents and his understanding of optical effects.

Role in Design Education and Reform

Owen Jones was deeply committed to improving the standard of design in Britain, particularly in relation to manufactured goods. He believed that good design was not merely a matter of aesthetics but also had social and economic importance. He was closely associated with Henry Cole, a key figure in Victorian design reform and the first director of the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum).

Jones played a role in the development of the collections and educational programs at the South Kensington Museum. His principles, particularly those articulated in The Grammar of Ornament, influenced the curriculum of the government-run Schools of Design. He advocated for a systematic approach to teaching design, emphasizing the study of historical examples not for direct imitation but for the extraction of underlying principles.

His efforts were part of a broader movement in Victorian Britain aimed at bridging the gap between art and industry. Reformers like Jones, Cole, and Ruskin (though often disagreeing on methods) sought to elevate public taste and improve the quality of British manufactures in the face of international competition. Jones believed that by understanding the fundamental "grammar" of ornament, designers could create beautiful and appropriate designs for the industrial age.

Contemporaries and Influences: A Rich Tapestry

Owen Jones operated within a vibrant and often contentious milieu of 19th-century architects, designers, and critics. His work and theories were shaped by, and in turn influenced, many of his contemporaries.

His early mentor, Lewis Vulliamy, provided his foundational architectural training. His collaboration with Jules Goury on the Alhambra project was pivotal. His work on the Crystal Palace brought him into close contact with its architect, Joseph Paxton, and the chief organizer of the Great Exhibition, Henry Cole. Cole remained a significant ally in the cause of design reform.

John Ruskin, perhaps the most influential art critic of the Victorian era, had a complex relationship with Jones's ideas. While Ruskin also championed craftsmanship and decried the shoddiness of much industrial production, his aesthetic preferences leaned towards naturalism and the Gothic style. He was initially critical of Jones's Crystal Palace color scheme and his emphasis on conventionalized, geometric ornament, which contrasted with Ruskin's belief in the moral and spiritual superiority of ornament derived directly from nature. However, both men shared a profound concern for the state of art and design in their society.

William Morris, a leading figure in the Arts and Crafts Movement, was undoubtedly influenced by The Grammar of Ornament. Morris's own designs for textiles and wallpapers, while developing a distinct and highly personal style rooted in natural forms, show an understanding of pattern structure and color harmony that aligns with some of Jones's principles. Both men rejected illusionistic representation in decorative design in favor of flat, stylized patterns.

Christopher Dresser is another key contemporary often compared to Jones. Dresser, a botanist by training, was a prolific designer who also advocated for conventionalized ornament and produced a vast range of designs for industrial production. Like Jones, Dresser studied historical and non-Western ornament and published his own theoretical works, such as Principles of Decorative Design (1873). Both men were pioneers in establishing design as a professional discipline.

Other important figures in the architectural and design debates of the time include A.W.N. Pugin, the fervent champion of the Gothic Revival, whose principles of "true" design (honesty of material and construction) resonated with some aspects of Jones's thinking, even if their stylistic preferences differed vastly. German architect and theorist Gottfried Semper, who also spent time in London, explored similar themes of style, materials, and the origins of ornament in his writings, contributing to the international discourse on design theory.

Architects like Matthew Digby Wyatt, who was also heavily involved in the Great Exhibition and wrote extensively on historical styles and industrial art, and Charles Locke Eastlake, whose book Hints on Household Taste (1868) advocated for simpler, more "artistic" furnishings, were part of this broader conversation about design reform. Even architects like George Gilbert Scott, a leading proponent of the Gothic Revival, or Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the great engineer, represent the diverse creative forces shaping the Victorian built environment, a context in which Jones's specific contributions to decorative theory and practice found their place. The work of illustrators and printers like Henry Noel Humphreys, who also experimented with chromolithography for ornate book designs, is also relevant to Jones's publishing endeavors.

Legacy and Critical Reception

Owen Jones's impact on design theory and practice has been profound and lasting. He is widely regarded as one of the most important design theorists of the 19th century. His advocacy for a rational, principled approach to ornament, his pioneering work in color theory, and his promotion of flat pattern design were highly influential.

The Grammar of Ornament remains his most significant achievement, a work that not only documented global ornamental traditions but also attempted to codify the universal principles underlying them. It provided generations of designers with an invaluable resource and a conceptual framework. His emphasis on conventionalization and geometric structure can be seen as a precursor to later modernist concerns with abstraction and formal order.

However, Jones's work has not been without criticism. Some have found his 37 propositions overly rigid or prescriptive. His interpretations of historical ornament have occasionally been questioned, and his embrace of diverse cultural styles, while broad, was inevitably viewed through a 19th-century European lens. The term "Savage Tribes" in The Grammar of Ornament, for example, reflects the colonial attitudes of his era, even as he sought to validate the aesthetic merit of their creations.

Despite these critiques, the overall assessment of Owen Jones's contribution is overwhelmingly positive. He was a visionary who sought to elevate the status of decorative art and to provide a rational basis for its creation and appreciation. He played a crucial role in the design reform movement in Britain and helped to shape the curriculum of design education. His influence extended beyond Britain, impacting design thinking internationally.

Conclusion: A Lasting Imprint on Design

Owen Jones died on April 19, 1874, leaving behind a rich legacy of built work, publications, and theoretical ideas. He was a tireless investigator of ornament, a bold innovator in the use of color, and a passionate advocate for the principles of good design. In an age of rapid industrialization and often chaotic eclecticism in the decorative arts, Jones sought to bring order, harmony, and intellectual rigor to the field.

His insistence on understanding the underlying "grammar" of design, his exploration of non-Western artistic traditions, and his efforts to bridge the gap between historical precedent and modern practice mark him as a key transitional figure, looking both to the past for inspiration and to the future for new modes of expression. The principles he championed continue to resonate in contemporary design, and his Grammar of Ornament remains a testament to the enduring power and beauty of decorative art from across the globe. Owen Jones was more than just an architect or designer; he was a profound thinker who helped to define the very language of modern ornament.