An Introduction to the Enigmatic Artist

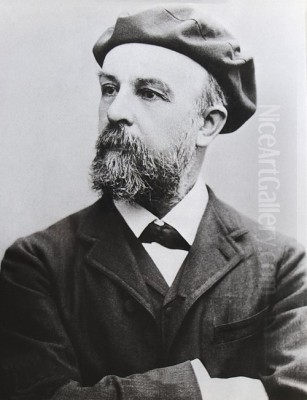

Odilon Redon, born Bertrand-Jean Redon in Bordeaux on April 20, 1840, and passing away in Paris on July 6, 1916, stands as a unique and pivotal figure in the landscape of French art. Primarily associated with Symbolism, his work transcends easy categorization, delving into the realms of dreams, fantasy, and the subconscious with a depth that anticipated Surrealism. His artistic journey is often characterized by two distinct periods: an early phase dominated by haunting charcoals and lithographs known as "noirs," and a later period bursting with vibrant pastels and oils. Redon's nickname, "Odilon," was affectionately derived from his mother's name, Odile, a Creole woman from Louisiana, adding a personal touch to the identity of this explorer of inner worlds. He remains a fascinating figure, whose art bridges the 19th-century's romantic and symbolist tendencies with the burgeoning modernism of the 20th century.

Redon's contribution lies not just in his technical skill across various media, but in his profound ability to visualize the unseen. He sought to make the invisible visible, translating complex emotions, spiritual anxieties, and fantastical visions into compelling imagery. Unlike many of his contemporaries who focused on the external world, Redon turned inward, charting the territories of the mind and spirit. His legacy is that of an artist who dared to explore the shadows and light of human consciousness, leaving behind a body of work that continues to intrigue and inspire with its mysterious beauty and psychological depth. He was a contemporary of the Impressionists but forged a path entirely his own, influencing generations of artists who followed.

Formative Years: Bordeaux, Peyrelebade, and Early Studies

Bertrand-Jean Redon entered the world in Bordeaux, France, into a family of considerable means, yet marked by complexities. His father, Bertrand Redon, had amassed wealth, partly through ventures in the American South, including, according to some accounts, involvement in the slave trade before Odilon's birth. His mother, Marie-Odile Guérin, was a French Creole from New Orleans, bringing a touch of the exotic and perhaps a different sensibility to the household. Despite the family's affluence, Redon's early childhood was marked by separation and solitude. Considered frail and possibly epileptic, he was sent away shortly after birth to live with an uncle at Peyrelebade, the family's wine-growing estate in the Médoc region near Bordeaux.

This extended period at Peyrelebade, lasting until he was around eleven, profoundly shaped the young Redon. The vast, somewhat desolate landscapes of the Médoc, combined with his relative isolation, fostered a deep sense of introspection and a powerful imagination. He spent long hours observing nature, lost in thought, developing a sensitivity to the nuances of light and shadow, and perhaps cultivating the inner world that would later dominate his art. Though lonely, this period was not without artistic encouragement. He began drawing at a young age, and by ten, he had already won a drawing prize at school, indicating an early inclination and talent for the visual arts. This solitary, nature-infused upbringing laid the groundwork for the melancholic and dreamlike qualities often found in his work.

Upon returning to his family in Bordeaux, Redon's formal education continued, but his artistic inclinations grew stronger. His family, recognizing his talent, arranged for him to study drawing with Stanislas Gorin, a local artist who specialized in watercolors. Gorin introduced him to the works of artists like Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot and Gustave Moreau, opening his eyes to different artistic possibilities beyond academic tradition. However, his father initially envisioned a more practical career for him in architecture. Redon dutifully pursued this path, traveling to Paris to study for the entrance examination to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. Despite his efforts, he failed the architectural examination, a setback that ultimately redirected him firmly towards painting and printmaking, the fields where he would make his unique mark.

The Influence of Rodolphe Bresdin and the Path to Printmaking

A pivotal encounter in Redon's artistic development occurred around 1864 when he met Rodolphe Bresdin in Bordeaux. Bresdin, an older, eccentric, and highly original printmaker, became a crucial mentor. Bresdin himself worked largely outside the mainstream art world, creating intricate, fantastical etchings and lithographs filled with dense detail and imaginative figures, often drawing on biblical or mythological themes. His dedication to the craft of printmaking and his unique visionary style left an indelible mark on the younger artist. Under Bresdin's tutelage, Redon learned the demanding techniques of etching and lithography, skills that would become central to his early career.

Bresdin's influence extended beyond mere technique. He encouraged Redon's imaginative tendencies and likely reinforced his interest in the strange and the visionary. Bresdin's own work, often described as a precursor to Symbolism, resonated with Redon's introspective nature and his burgeoning fascination with the world beyond surface appearances. The meticulous detail required in printmaking perhaps appealed to Redon's focused temperament, while the medium itself, particularly lithography with its rich blacks and tonal possibilities, proved ideal for exploring the themes of darkness, shadow, and mystery that characterized his early work. This mentorship provided Redon not only with technical mastery but also with validation for pursuing a highly personal and unconventional artistic path.

The skills Redon acquired from Bresdin were fundamental to the creation of his "noirs." Lithography, in particular, allowed him to achieve deep, velvety blacks and subtle gradations of tone, perfect for evoking the dreamlike, often unsettling atmosphere of these works. Etching provided another avenue for linear expression and detailed rendering. Redon's dedication to these graphic media during the 1870s and 1880s set him apart from many contemporaries who were primarily focused on painting. His mastery of black and white became a hallmark of his early style, demonstrating that profound emotional and psychological depth could be conveyed without resorting to color. The encounter with Bresdin was thus a turning point, equipping Redon with the tools and confidence to embark on his unique exploration of the invisible.

The Realm of Shadows: The Power of the "Noirs"

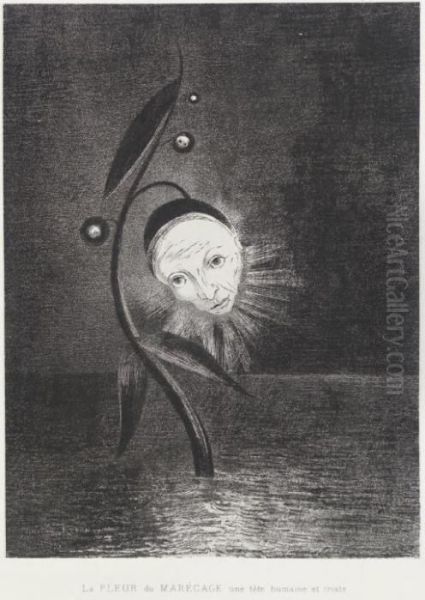

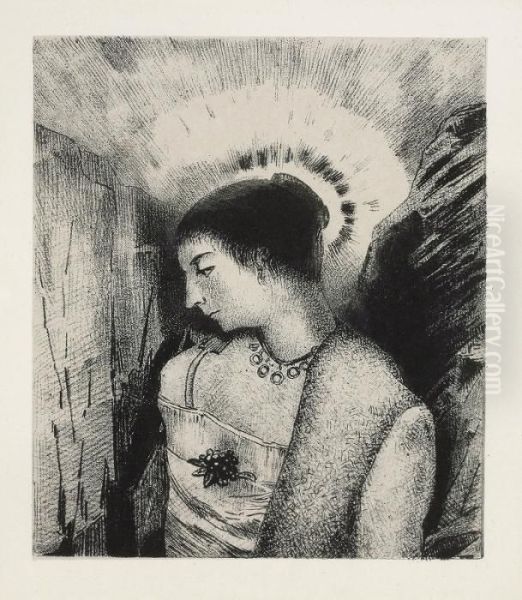

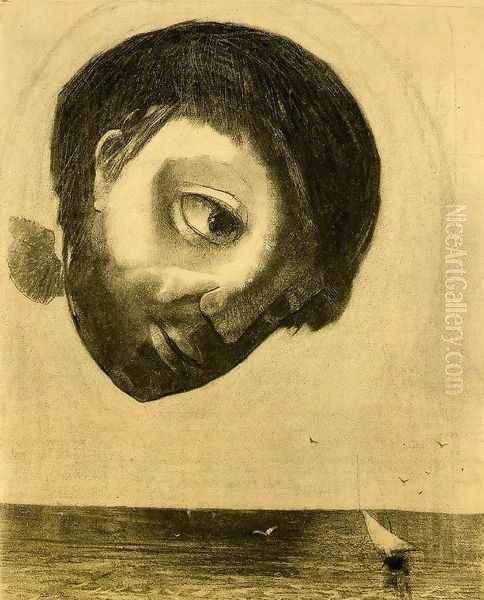

From the 1870s through the early 1890s, Odilon Redon dedicated himself primarily to working in black and white, producing a remarkable body of charcoal drawings (fusains) and lithographs that he collectively termed "noirs" (blacks). This period established his reputation as a master of shadow and suggestion, an artist plumbing the depths of the human psyche. These works are characterized by their mysterious, often unsettling imagery, drawing from dreams, nightmares, literature, and a fascination with the grotesque and the fantastical. The deep, velvety blacks achieved through charcoal and lithography became his signature, creating a world steeped in ambiguity and psychological intensity.

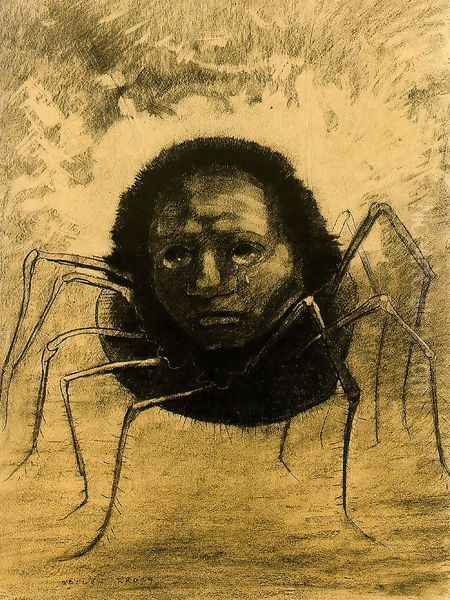

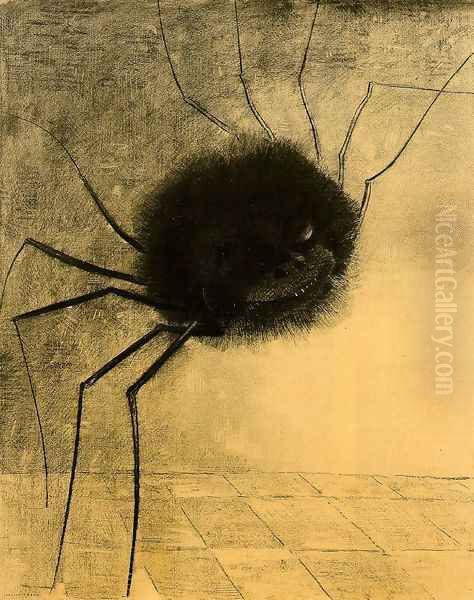

The subjects of the "noirs" are incredibly varied but consistently strange and evocative. We encounter disembodied eyes floating like balloons, smiling spiders with human faces, hybrid creatures, melancholic figures lost in contemplation, and scenes inspired by scientific observation transformed into bizarre visions. Redon produced several significant lithographic albums during this time, including Dans le Rêve (In the Dream, 1879), Hommage à Goya (Homage to Goya, 1885), La Nuit (Night, 1886), and series inspired by Gustave Flaubert's The Temptation of Saint Anthony (1888, 1889, 1896). These series allowed him to explore themes sequentially, developing narratives of inner turmoil, spiritual quest, and the confrontation with the unknown.

Key individual works from this era exemplify his unique vision. The Guardian Spirit of the Waters (c. 1878), an early charcoal, gained him some recognition and shows his ability to imbue natural forms with mysterious presence. The Crying Spider (1881) and The Smiling Spider (1887) are iconic examples of his anthropomorphized creatures, blending the mundane with the monstrous to evoke complex emotions, perhaps reflecting anxieties about life and nature. The Eye, like a strange balloon, moves towards Infinity (plate I from Hommage à Goya) is another unforgettable image, suggesting surveillance, aspiration, or the soul's journey. These works resonated strongly with the Symbolist literary movement, particularly with writers like Joris-Karl Huysmans, who famously described Redon's art in his novel À Rebours (Against Nature), bringing the artist wider attention among the avant-garde. The "noirs" remain perhaps Redon's most distinctive contribution, showcasing his mastery of chiaroscuro and his unparalleled ability to give form to the intangible.

A Turn Towards Color: Pastels, Oils, and New Visions

Around the early 1890s, a significant shift occurred in Odilon Redon's work. While he never entirely abandoned black and white, he increasingly embraced color, working extensively in pastels and oils. This transition marked a move away from the predominantly dark and often disturbing themes of the "noirs" towards a world filled with light, vibrant hues, and a more serene, mystical, or decorative sensibility. The reasons for this shift are debated – perhaps influenced by personal happiness (his marriage to Camille Falte in 1880 and the birth of his son Arï in 1889 after the earlier loss of an infant son), a natural artistic evolution, or exposure to the color experiments of contemporaries. Whatever the cause, this later phase revealed a different facet of Redon's artistic personality.

Pastel, with its powdery texture and potential for luminous, blended color, became a favored medium. Oil painting also featured more prominently. His subject matter expanded, though retaining a connection to the mysterious and the symbolic. Flower studies became a major preoccupation, but these were rarely straightforward botanical illustrations. Redon depicted bouquets and single stems – poppies, anemones, wildflowers – in simple vases, isolating them against ambiguous, often richly colored backgrounds. These floral works possess a dreamlike intensity, the blossoms seeming to radiate an inner light, symbolizing perhaps fragility, beauty, or spiritual essence. They became highly sought after by collectors.

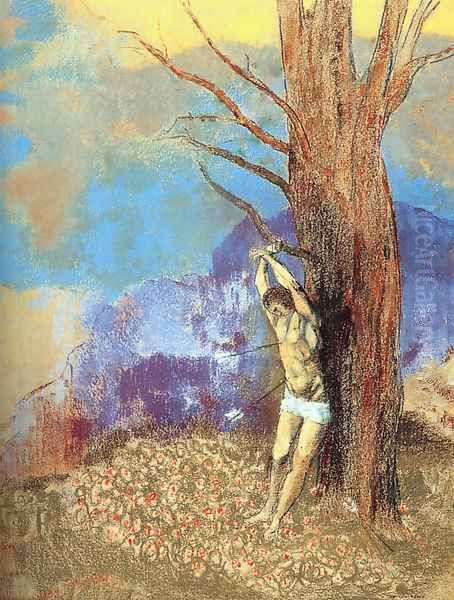

Mythological and spiritual themes also flourished during his color period. Works like The Cyclops (c. 1914), depicting the giant Polyphemus gazing tenderly at the sleeping Galatea, blend myth with a strange, almost childlike vulnerability. The Chariot of Apollo (c. 1905-1914), a theme he revisited multiple times, explodes with dynamic light and color, suggesting cosmic energy. He explored Christian themes (Saint Sebastian) and figures from Eastern spirituality, notably Buddha (c. 1906-1907), often depicted in serene meditation amidst radiant light or lush nature. Closed Eyes (1890), an oil painting often seen as a transitional work, portrays a figure in quiet contemplation, suggesting a turn inward towards spiritual illumination, rendered with a newfound softness and subtle color harmony. This later period also saw Redon undertake decorative commissions, such as the large panels for the Château de Domecy-sur-le-Vault (c. 1900-1901), demonstrating his ability to apply his visionary style to architectural contexts.

Sources of Inspiration: Literature, Science, and Spirituality

Odilon Redon's unique artistic vision was fueled by a diverse range of interests and inspirations that extended far beyond the visual arts. Literature was a profound source, particularly the works of writers who explored the darker, more mysterious aspects of human experience. Edgar Allan Poe's tales of the macabre and the psychological resonated deeply, influencing the mood and sometimes the imagery of the "noirs." The Symbolist poets, especially Charles Baudelaire with his exploration of beauty found in decay and the artificial (Les Fleurs du Mal), and Stéphane Mallarmé, whose suggestive, evocative language paralleled Redon's visual ambiguity, were kindred spirits. Redon created specific lithographic series directly inspired by Gustave Flaubert's The Temptation of Saint Anthony, finding rich visual potential in the novel's hallucinatory visions and spiritual struggles.

Science, surprisingly, was another significant wellspring for Redon's imagination. He was fascinated by the discoveries emerging in biology and natural history during his lifetime, particularly the theories of Charles Darwin and the burgeoning field of microbiology. His friendship with the botanist Armand Clavaud in Bordeaux introduced him to the microscopic world, revealing strange and intricate forms invisible to the naked eye. This exposure seems to have directly inspired some of his more bizarre creations – hybrid creatures, cellular forms, and plant-animal amalgams. Redon saw nature not just as a source of beauty but as a realm of constant transformation and hidden wonders, where the monstrous and the beautiful could coexist, reflecting a deeper, perhaps unsettling, reality.

Spirituality and mysticism formed the third pillar of his inspiration. While raised Catholic, Redon's spiritual interests were broad and syncretic. He was drawn to the introspective and philosophical aspects of Buddhism and Hinduism, which became increasingly evident in his later color works featuring figures like the Buddha or exploring themes of enlightenment and transcendence. His work often grapples with universal questions about life, death, the nature of reality, and the human soul's place in the cosmos. This spiritual dimension infuses his art with a sense of mystery and profundity, whether depicting a floating eye, a radiant flower, or a meditative figure. His art became a vehicle for exploring these inner landscapes and spiritual quests, translating complex ideas and emotions into powerful visual symbols.

Redon and Symbolism: Capturing the Inner World

Odilon Redon is considered one of the foremost figures of the Symbolist movement in art, which flourished in Europe, particularly France, during the late 19th century. Symbolism emerged partly as a reaction against the perceived objectivity and materialism of Realism and Impressionism. Instead of depicting the external world accurately, Symbolist artists sought to express ideas, emotions, and subjective states through suggestive forms, colors, and symbols. They aimed to evoke rather than describe, tapping into dreams, myths, legends, and personal psychological experiences to explore deeper truths or spiritual realities. Redon's art, with its focus on the inner world, its dreamlike imagery, and its ambiguous meanings, perfectly embodied the core tenets of the movement.

While associated with other prominent Symbolist painters like Gustave Moreau, known for his richly detailed mythological scenes, and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, famed for his serene, allegorical murals, Redon's approach was distinctly personal and introspective. His "noirs," in particular, offered a darker, more psychologically charged vision than the work of many other Symbolists. He shared with them an interest in literature, mythology, and spirituality, but his visual language remained uniquely his own, characterized by its often bizarre juxtapositions and its profound exploration of the subconscious. He was less concerned with traditional allegory and more focused on creating resonant images that tapped directly into the viewer's imagination and emotions.

Redon's connection to the Symbolist milieu extended to the literary world. As mentioned, writers like Joris-Karl Huysmans and Stéphane Mallarmé championed his work, recognizing in his art a visual counterpart to their own literary aims. He exhibited alongside other Symbolist artists, notably at the exhibitions of Les XX (The Twenty) in Brussels, an avant-garde group receptive to new and unconventional art. While Paul Gauguin, another major figure associated with Symbolism, developed his own style of "Synthetism" emphasizing flat color planes and simplified forms, Redon pursued a path more rooted in chiaroscuro (in his noirs) and later, a unique luminosity (in his color work). Within the diverse landscape of Symbolism, Redon stands out for the sheer originality of his vision and his pioneering exploration of the psychological depths that would later fascinate the Surrealists.

Recognition and International Presence

Despite the profound originality of his work, Odilon Redon achieved widespread recognition relatively late in his career. During the 1870s and much of the 1880s, while diligently producing his "noirs," he remained largely unknown to the broader public and even to many in the Parisian art establishment. His introspective nature and his focus on the unconventional medium of charcoal and lithography kept him somewhat isolated from the mainstream Impressionist movement that dominated the Parisian scene at the time. His early supporters were primarily fellow artists, critics, and writers associated with the Symbolist movement, who appreciated the unique psychological depth and imaginative power of his creations.

The publication of Joris-Karl Huysmans' novel À Rebours in 1884 marked a turning point. The novel's decadent protagonist, Des Esseintes, collects Redon's disturbing prints, and Huysmans' vivid descriptions brought the artist's name to the attention of a wider avant-garde audience. Invitations to exhibit followed, including participation in the final Impressionist exhibition in 1886 (though his work stood apart stylistically) and shows with the progressive group Les XX in Brussels. Durand-Ruel, the famed dealer associated with the Impressionists, also began to show his work. The shift towards color in the 1890s further broadened his appeal, with his vibrant pastels and oils finding favor with collectors.

Redon's reputation eventually extended beyond France and Belgium. He gained admirers across Europe and, significantly, in the United States. His inclusion in the landmark Armory Show of 1913, held in New York City, Chicago, and Boston, was crucial for establishing his international stature. This exhibition introduced European modernism on a large scale to American audiences, and Redon was prominently featured, with more works included than any other artist. His mystical, colorful, and imaginative paintings and pastels captivated viewers and influenced American artists and collectors. By the time of his death in 1916, Redon had transitioned from a relatively obscure printmaker appreciated by a small circle to an internationally recognized master whose work was acknowledged as a vital link between 19th-century traditions and 20th-century modernism.

Legacy and Influence: A Precursor to Modernism

Odilon Redon's legacy in art history is significant and multifaceted. He is widely regarded not only as a major figure within Symbolism but also as a crucial precursor to several key movements of 20th-century art, most notably Surrealism. His deep dive into the subconscious, his exploration of dream imagery, and his creation of fantastical, often unsettling hybrid forms laid essential groundwork for artists who sought to unlock the power of the irrational mind. André Breton, the founder of Surrealism, explicitly acknowledged Redon's importance, and his influence can be seen in the works of Surrealist painters like Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Yves Tanguy, and Joan Miró, who similarly drew upon dreams and automatism.

Beyond Surrealism, Redon's impact extended to artists exploring color and form. His later works, with their vibrant, non-naturalistic use of color and their emphasis on expressive potential, resonated with the Fauves. Henri Matisse, a leader of the Fauvist movement, owned Redon's work and admired his innovative approach to color, which prioritized emotional and decorative qualities over realistic representation. The Nabis, a group active in the 1890s that included Maurice Denis, Édouard Vuillard, and Pierre Bonnard, also found inspiration in Redon. They shared his interest in Symbolism, spirituality, decorative arts, and the subjective interpretation of reality, seeing him as an important elder figure who had forged a path away from Impressionism towards a more personal and symbolic art.

Redon occupies a unique position as a bridge figure. His roots were in the 19th century, influenced by Romanticism (like Goya, whom he admired) and mentored by the idiosyncratic Bresdin. Yet, his explorations of internal states, his formal innovations in both black and white and color, and his embrace of the irrational pushed the boundaries of art in ways that anticipated modernism. While contemporaries like Vincent van Gogh explored emotional intensity through expressive brushwork and color, and Paul Cézanne investigated underlying structure, Redon charted the equally revolutionary territory of the inner world. His influence wasn't about founding a specific school but about opening up possibilities for art to explore the invisible realms of thought, emotion, and spirit, making him a profoundly modern artist whose work continues to feel relevant. His willingness to follow a singular vision, regardless of prevailing trends, serves as an enduring model for artistic integrity.

Conclusion: The Enduring Mystery of Odilon Redon

Odilon Redon remains one of art history's most intriguing and individualistic figures. From the shadowy depths of his "noirs" to the luminous radiance of his later pastels and oils, his work consistently invites viewers into a world beyond the surface of reality. He masterfully employed charcoal, lithography, pastel, and oil paint to give form to the intangible – dreams, fears, spiritual aspirations, and the hidden life within nature. His journey from the dark, introspective visions of his early career to the vibrant, mystical explorations of his later years reflects a complex artistic and perhaps personal evolution, yet always retains a core commitment to the power of the imagination.

As a key Symbolist, he translated the movement's literary and philosophical concerns into a compelling visual language. As a precursor to Surrealism, he opened the door to the exploration of the subconscious that would dominate much of 20th-century art. His unique synthesis of influences – from Goya and Poe to Darwin and Buddha – resulted in an art that is both deeply personal and universally resonant. Redon's legacy lies in his unwavering dedication to his inner vision, his technical mastery across diverse media, and his profound ability to make us see the world, and ourselves, in a new, more mysterious light. His art continues to challenge, fascinate, and inspire, securing his place as a quiet revolutionary and an enduring master of the invisible.