Baccio Bandinelli, a name that resonates with the grandeur and turbulence of the Italian High Renaissance and early Mannerism, remains one of the most fascinating and often contentious figures in the history of art. Born Bartolomeo Brandini, likely around October 7, 1493, in the Florentine region (though some earlier sources, including Vasari, cite 1488), he died in Florence on February 7, 1560. He was a sculptor, painter, and draftsman of considerable talent, whose career was marked by prestigious commissions, intense rivalries, and a personality that often overshadowed his artistic achievements in the eyes of his contemporaries. This exploration delves into his life, his major works, his distinctive style, his complex relationships with other artists, and his enduring, if debated, legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Baccio Bandinelli's journey into the world of art began in the bustling artistic crucible of Florence. His father, Michelangelo di Viviano de Brandini of Gaiole, was a prominent goldsmith, and it was in his father's workshop that Baccio received his initial training. This grounding in goldsmithing, a common starting point for many Renaissance artists including figures like Filippo Brunelleschi and Donatello, would have instilled in him a meticulous attention to detail and a proficiency in working with metals. His family later adopted the more distinguished surname Bandinelli, claiming descent from a noble Sienese family.

Bandinelli, however, soon demonstrated an aptitude and ambition that extended beyond the confines of the goldsmith's craft. He showed an early interest in sculpture and, according to Giorgio Vasari, his principal biographer (and sometimes critical contemporary), he studied under Giovanni Francesco Rustici. Rustici was a sculptor known for his bronze work and had connections to Leonardo da Vinci, whose influence, particularly in the dynamic rendering of figures, may have filtered through to the young Baccio. During these formative years, Bandinelli would have been immersed in the study of classical antiquity and the works of earlier Florentine masters like Donatello, whose powerful expressiveness he is said to have emulated in his youth. He was also a prodigious draftsman, a skill that would underpin all his artistic endeavors.

The Ascent: Patronage and Major Commissions

Bandinelli's talent and relentless ambition did not go unnoticed. He actively sought and secured patronage from the highest echelons of society, including the powerful Medici family, who were significant patrons of the arts in Florence, and several Popes in Rome. His career flourished under Medici Popes Leo X and Clement VII, and later under Duke Cosimo I de' Medici in Florence.

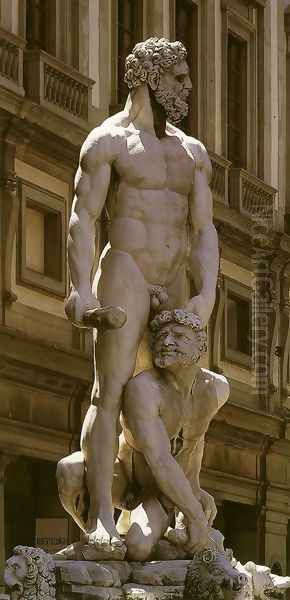

One of his earliest significant commissions was a Saint Peter in marble for the Duomo (Florence Cathedral), demonstrating his capabilities in large-scale sculpture. However, it was the commission for the colossal marble group of Hercules and Cacus (1527-1534) that truly thrust him into the spotlight, and also into the heart of artistic controversy. This statue was intended to stand as a pendant to Michelangelo Buonarroti's iconic David outside the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. The commission had originally been considered for Michelangelo, but political and artistic machinations, coupled with Michelangelo's other commitments, led to Bandinelli securing the project.

The unveiling of Hercules and Cacus was met with a storm of criticism, much of it fueled by supporters of Michelangelo and by Bandinelli's own abrasive personality. Critics, including fellow artist Benvenuto Cellini, derided the work for its perceived awkwardness, exaggerated musculature (Cellini famously likened Hercules' muscles to a "sack of melons"), and lack of the grazia (grace) and terribilità (awesomeness) associated with Michelangelo. Despite the criticism, the statue remains a powerful, if somewhat brutish, testament to Bandinelli's technical skill in carving marble on a monumental scale and his engagement with the classical theme of heroic strength.

Bandinelli also undertook significant projects in Rome. For Pope Leo X, he worked on reliefs for St. Peter's Basilica. For Pope Clement VII, he began work on the tombs of Leo X and Clement VII himself in Santa Maria sopra Minerva, though these were later completed by others, including Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and Raffaello da Montelupo. He also created a renowned copy of the ancient Laocoön and His Sons group for Cardinal Giulio de' Medici (later Clement VII), which was intended as a gift for King Francis I of France. Though the original plan changed and the copy remained in Florence (now in the Uffizi Gallery), it was highly praised and demonstrated Bandinelli's deep understanding and appreciation of classical sculpture. Jacopo Sansovino also made a famous wax model of the Laocoön around the same time, highlighting the intense interest in this particular ancient masterpiece.

Back in Florence, under Duke Cosimo I, Bandinelli received numerous commissions. Among the most ambitious was the design and execution of the choir enclosure (recinto del coro) and high altar for Florence Cathedral (Santa Maria del Fiore). This massive project, begun in the 1540s, involved numerous marble statues and reliefs, including figures of Adam and Eve (now in the Bargello Museum), God the Father, and eighty-eight relief panels depicting prophets and scenes from the Old Testament. While much of this structure was dismantled in the 19th century, the surviving elements showcase Bandinelli's organizational abilities and his capacity to manage a large workshop. He also designed the Udienza (audience hall) in the Palazzo Vecchio, including its elaborate coffered ceiling.

Other notable commissions included reliefs for the Santa Casa in Loreto, a project that involved other prominent artists like Andrea Sansovino, and various portrait busts and smaller sculptures. He was also involved in designing ephemeral decorations for state occasions, a common task for court artists of the period.

Artistic Style: Disegno, Anatomy, and Classicism

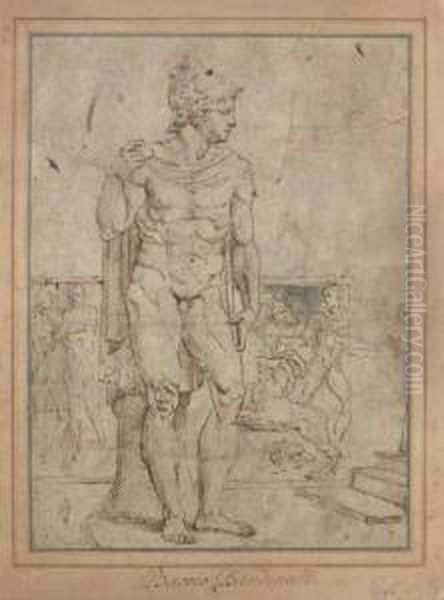

Bandinelli's artistic style is characterized by a strong emphasis on disegno – the Italian concept encompassing both drawing and design, considered the foundation of all visual arts during the Renaissance. He was an exceptionally prolific and skilled draftsman. Thousands of his drawings survive, ranging from quick sketches and compositional studies to highly finished anatomical renderings and presentation drawings. These drawings reveal his meticulous study of human anatomy, often featuring powerful, muscular nudes in complex, sometimes contorted, poses. His anatomical knowledge was profound, though critics sometimes felt his figures appeared overly muscular or "muscle-bound," lacking natural fluidity.

His sculptural style is marked by a robust monumentality and a clear debt to classical antiquity. He sought to imbue his figures with a heroic grandeur, often choosing subjects from mythology or biblical history that allowed for dramatic and powerful representations. Works like Hercules and Cacus and his Laocoön copy exemplify this classical leaning. There's a certain hardness and precision in his carving, which can be contrasted with the more nuanced and emotionally resonant surfaces of Michelangelo or the softer modeling of some of his contemporaries.

While deeply influenced by the High Renaissance ideals of clarity and order, Bandinelli's work also exhibits traits that align with the emerging Mannerist style. Mannerism, which developed in the decades following the High Renaissance, often featured elongated figures, exaggerated poses, a heightened sense of artificiality, and a focus on technical virtuosity. Bandinelli's emphasis on complex contrapposto, his sometimes strained figural compositions, and his evident desire to display his technical prowess can be seen as contributing to this stylistic shift. Artists like Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino, his Florentine contemporaries, were key figures in the development of early Mannerism in painting, and Bandinelli's sculpture shares some of its restless energy and stylistic self-consciousness.

Bandinelli also engaged with painting, though sculpture remained his primary focus. His paintings, like his self-portrait in the Uffizi, show a similar sculptural quality in the definition of form. He also produced designs for engravings, further disseminating his compositions.

A Contentious Figure: Rivalries and Reputation

Baccio Bandinelli's artistic career is inextricably linked with his notoriously difficult personality. He was described by contemporaries, most notably Vasari and Cellini, as arrogant, envious, and malicious. He seemed to thrive on conflict and actively sought to denigrate the work of his rivals, a trait that earned him many enemies and undoubtedly colored the reception of his own art.

His most famous and enduring rivalry was with Michelangelo. Bandinelli was intensely jealous of Michelangelo's towering reputation and seemed to measure his own success against that of the older master. The Hercules and Cacus commission was a focal point of this rivalry, with Bandinelli explicitly trying to create a work that could stand alongside, or even surpass, Michelangelo's David. Vasari recounts an infamous incident where Bandinelli, out of envy, allegedly destroyed Michelangelo's preparatory cartoon for the Battle of Cascina, a fresco intended for the Palazzo Vecchio (a project that also involved Leonardo da Vinci, who was commissioned to paint the Battle of Anghiari in the same hall). While the full truth of this story is debated, it reflects the perception of Bandinelli's character.

Benvenuto Cellini, another fiercely competitive and outspoken artist, was a particularly bitter enemy of Bandinelli. Cellini's autobiography is filled with scathing anecdotes about Bandinelli, portraying him as incompetent, boorish, and deceitful. Their public arguments were legendary in Florence. Cellini, for instance, famously criticized Bandinelli's restoration of an antique torso (the "Bandinelli Hercules") and mocked his attempts to secure commissions. When Cellini's Perseus with the Head of Medusa was unveiled, Bandinelli was reportedly among its harshest critics, likely fueling Cellini's animosity further.

Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, provides a more measured but still critical account of Bandinelli. While acknowledging Bandinelli's skill, diligence, and ambition, Vasari also points out his arrogance, his tendency to speak ill of others, and a certain lack of "genius" or inventive spark compared to artists like Michelangelo. Vasari himself had briefly been a pupil in Bandinelli's workshop, giving him firsthand insight.

This difficult personality undoubtedly impacted how his art was received during his lifetime and in the centuries immediately following his death. His desire for recognition was immense; he was knighted by both Pope Clement VII and Emperor Charles V, and he established his own "Academy" in Rome and later in Florence, attempting to position himself as a leading artistic authority.

The Bandinelli Academy and His Influence

Despite his personal failings, Bandinelli was an influential figure. He established a workshop and a form of private academy, attracting a number of pupils and assistants. His emphasis on rigorous training in drawing, anatomy, and the study of classical models was significant. Among those who spent time in his studio or were influenced by him were Giorgio Vasari (briefly), Francesco Salviati (a notable Mannerist painter), and Bartolomeo Ammannati (who would later become a rival and complete some projects Bandinelli had started, such as the Neptune Fountain in the Piazza della Signoria, a commission Bandinelli had coveted).

His numerous drawings served as models for his students and were widely admired and collected. Through his teaching and the dissemination of his designs, Bandinelli contributed to the development of Florentine art in the mid-16th century, particularly within the Mannerist idiom. His insistence on technical proficiency and his engagement with classical forms provided a model, even if his personal style was not always emulated directly. Other artists active in Florence during this period, such as the court painter Agnolo Bronzino, would have been well aware of Bandinelli's prominent position and his artistic output.

Later Years, Death, and Shifting Legacy

Bandinelli remained active into his later years, continuing to work on major projects like the Florence Cathedral choir and undertaking new commissions. He amassed considerable wealth and property, a testament to his success in securing patronage despite his difficult nature. He also worked on his own funerary chapel in the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata in Florence, for which he sculpted a poignant Pietà (now in the church of Santa Croce) that was intended for his own tomb, depicting himself as Nicodemus supporting the body of Christ. This work shows a more personal and perhaps more introspective side to the artist.

His son, Giuliano Bandinelli, also became an artist and assisted his father, though he did not achieve the same level of fame. Baccio Bandinelli died in Florence in 1560 and was buried in his family chapel in Santissima Annunziata.

For a long time, Bandinelli's posthumous reputation was largely shaped by the negative accounts of Vasari and Cellini. He was often dismissed as a technically proficient but uninspired artist, a mere imitator whose ambition outstripped his talent. However, in the 20th and 21st centuries, art historians have undertaken a more nuanced re-evaluation of his work. Scholars now recognize his significant contributions as a draftsman, his role in the dissemination of classical ideals, and his importance as a major figure in 16th-century Florentine sculpture. His ability to manage large-scale sculptural projects and his undeniable technical skill are more appreciated. While the criticisms of his personality and some aspects of his art remain valid, his place as a key, if complex, protagonist in the artistic landscape of the Renaissance is now more firmly established. Artists like Leone Leoni, another contemporary sculptor known for his powerful style and courtly connections, operated in a similar sphere of patronage and ambition, highlighting the competitive nature of the era.

Conclusion: An Enduring Enigma

Baccio Bandinelli remains an artist who elicits strong reactions. He was a man of immense drive, considerable skill, and profound learning, yet his career was perpetually dogged by his own contentious nature and the towering shadow of Michelangelo. His sculptures, particularly works like Hercules and Cacus and the choir reliefs for Florence Cathedral, are significant monuments of their time, reflecting both the classical aspirations of the High Renaissance and the stylistic innovations of early Mannerism. His drawings, in particular, stand as a testament to his mastery of disegno and his deep understanding of the human form.

While he may never be as universally beloved as Michelangelo or Raphael Sanzio, Bandinelli's contributions to the art of the 16th century are undeniable. He was a pivotal figure in the Florentine art scene, a prolific creator, and a sculptor who left an indelible mark on the cities of Florence and Rome. His story is a compelling reminder that artistic genius and personal likeability do not always go hand in hand, and that the narrative of art history is often as complex and multifaceted as the individuals who shape it. His ambition, his rivalries, and his powerful, if sometimes unsettling, art continue to fascinate and provoke discussion, securing his place as one of the Renaissance's most intriguing and enduring figures.