Rosa Bonheur stands as a colossus in nineteenth-century art, a figure whose talent and determination carved a unique path through a world often resistant to female ambition. Born Marie-Rosalie Bonheur in Bordeaux, France, on March 16, 1822, she rose to become one of the most celebrated painters of her era, renowned particularly for her powerful and meticulously observed depictions of animals. Her life (1822-1899) spanned a period of significant social and artistic change, and she was not merely an observer but an active participant, challenging conventions both on canvas and in her personal life. Her legacy is defined by technical mastery, an unwavering commitment to realism, and an independent spirit that continues to inspire.

Bonheur's fame was not confined to France; she achieved remarkable international success, particularly in Great Britain and the United States. Her monumental work, The Horse Fair, became one of the most famous paintings of the century, solidifying her reputation as a master of animal painting. Yet, her significance extends beyond her artistic output. As the first woman artist to be awarded the Grand Cross of the French Legion of Honour, and through her unconventional lifestyle, she became a symbol of female empowerment and artistic dedication, leaving an indelible mark on the history of art.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Rosa Bonheur's entry into the world of art was perhaps preordained. She was the eldest child of Sophie Marquis, a piano teacher, and Oscar-Raymond Bonheur, a landscape and portrait painter. Her father, though talented, struggled financially but was a man of progressive ideas, notably adhering to Saint-Simonianism, a socialist philosophy advocating for gender equality. This environment undoubtedly shaped Rosa's outlook and fostered her burgeoning independence from a young age. The family, which included younger siblings Auguste, Isidore, and Juliette, all of whom would also become artists, moved to Paris in 1828.

Her early formal education was fraught with difficulty. Known for her boisterous and independent nature, she was deemed disruptive and expelled from several schools. Attempts to apprentice her to a seamstress proved disastrous, as her passion lay elsewhere. Recognizing her undeniable artistic inclination, Raymond Bonheur eventually took her education into his own hands around the age of thirteen. He became her primary, indeed her only formal, art teacher, guiding her through the fundamentals of drawing and painting.

Under her father's tutelage, Bonheur received a rigorous, albeit unconventional, artistic grounding. She copied images from drawing books, sketched from plaster casts, and, crucially, began studying masterworks firsthand at the Louvre. There, she diligently copied paintings by artists such as Nicolas Poussin, Peter Paul Rubens, and Dutch Golden Age animaliers like Paulus Potter and Aelbert Cuyp, absorbing lessons in composition, technique, and the realistic depiction of form and light. This period of intense study laid the foundation for her technical proficiency.

Raymond Bonheur's teaching methods extended beyond mere copying. He encouraged direct observation of nature, taking Rosa and her siblings on sketching trips to the countryside. Most importantly, he supported her burgeoning interest in animals, allowing her to bring pets into the family home and studio for close study. This early immersion in both artistic tradition and direct observation proved critical in shaping her unique artistic voice, steering her definitively towards the subject matter that would define her career: the animal kingdom.

Developing a Unique Vision: The Path to Animal Painting

While her father specialized in landscapes, Rosa Bonheur quickly gravitated towards animals. This was not merely a choice of subject but a deep-seated passion. She possessed an innate empathy for animals and a fascination with their anatomy, movement, and character. Her father encouraged this specialization, recognizing her exceptional talent in capturing their essence. This focus set her apart, particularly as animal painting, or animalier art, while respected, was not always considered the highest form of artistic expression compared to history painting.

Bonheur's commitment to realism demanded intense, firsthand study. Simple observation from afar was insufficient; she needed to understand the underlying structure, the play of muscles beneath the skin, the very mechanics of animal locomotion. This led her to pursue methods considered highly unconventional, even shocking, for a woman in the mid-nineteenth century. She frequented Parisian horse markets, such as the famed Marché aux chevaux, livestock markets, and even abattoirs (slaughterhouses) to sketch directly from life and study animal anatomy up close.

Accessing these male-dominated environments presented significant challenges. To move freely and avoid unwanted attention, Bonheur adopted male attire. She cut her hair short and wore trousers and a smock, practical clothing that allowed her to navigate muddy stockyards and crowded markets without hindrance. This was not merely a fashion statement but a professional necessity. So unusual was this practice that in 1857, she obtained official police permission – a permission de travestissement – renewable every six months, legally allowing her to wear men's clothing in public for health and professional reasons.

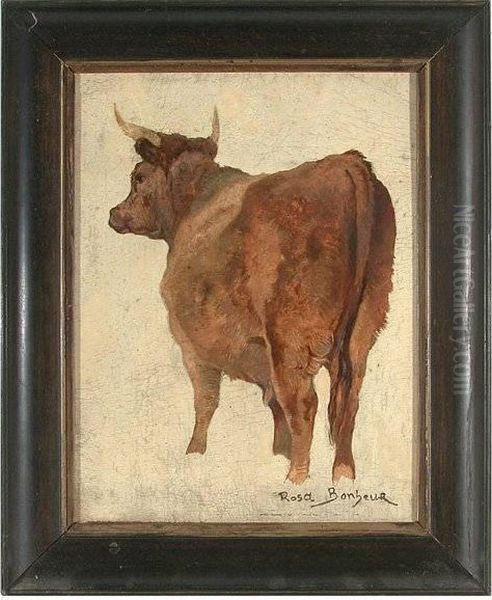

This dedication to empirical study, bordering on the scientific, became a hallmark of her practice. She dissected animals obtained from butchers to gain intimate knowledge of their musculature and skeletal structure, mirroring the anatomical investigations of earlier masters like George Stubbs, the renowned English painter of horses. This rigorous approach imbued her paintings with an anatomical accuracy and lifelike vitality that astounded viewers and critics alike, distinguishing her work from more sentimental or purely decorative animal depictions.

The Rise to Prominence: Realism and Recognition

Bonheur began exhibiting her work regularly at the prestigious Paris Salon from 1841 onwards, initially showing small paintings and sculptures. Her talent was quickly recognized, and she won several awards, including a third-class medal in 1845 and a gold medal in 1848. The turning point in her career came in 1849 with the exhibition of Ploughing in the Nivernais (Labourage nivernais). This large-scale painting, depicting powerful oxen tilling the soil in a specific region of France, was commissioned by the French government following her 1848 Salon success.

Ploughing in the Nivernais was a triumph. Critics lauded its realism, its unsentimental portrayal of rural labor, and its masterful depiction of the oxen, capturing their strength and patient toil. The painting resonated with the growing taste for Realism, a movement championed by artists like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, which focused on depicting ordinary life and the contemporary world with truthfulness. Bonheur's work, however, focused primarily on the animal world within this realistic framework. The painting's success cemented her reputation as a major artistic talent.

Building on this momentum, Bonheur embarked on her most ambitious project yet: The Horse Fair (Le marché aux chevaux). Inspired by the bustling horse market on the Boulevard de l'Hôpital in Paris, she spent eighteen months producing preparatory sketches and studies, often visiting the market twice weekly, dressed in her customary male attire for ease of access and work. The resulting canvas, completed in 1853, was monumental, measuring over eight feet high and sixteen feet wide.

Exhibited at the 1853 Salon, The Horse Fair caused a sensation. Its dynamic composition, depicting a turbulent scene of powerful Percheron horses being paraded and controlled by grooms, was breathtaking in its energy and scale. The anatomical accuracy of the horses, the realistic rendering of light and movement, and the sheer ambition of the undertaking garnered widespread acclaim. It was hailed as a masterpiece, establishing Bonheur not just as France's foremost animal painter but as one of the leading artists of her generation, male or female.

Artistic Style and Technique

Rosa Bonheur's art is firmly rooted in the Realist tradition. Her primary goal was the truthful and accurate representation of her subjects, particularly animals, based on meticulous observation and deep anatomical understanding. She eschewed the overt sentimentality found in the work of some contemporaries, aiming instead for a depiction that conveyed the inherent dignity, power, and character of the animals themselves. Her work celebrated the natural world and the creatures within it, often placing them in carefully rendered landscape settings.

Her technique was characterized by precise drawing and a relatively smooth, highly finished surface, aligning her more with academic traditions than with the looser brushwork emerging in French painting at the time (which would later culminate in Impressionism). She built up her forms with careful layering of paint, paying close attention to texture – the rough hide of cattle, the sleek coat of a horse, the dense wool of sheep. Her mastery of light and shadow was crucial in creating convincing three-dimensional forms and conveying atmosphere.

Bonheur's deep knowledge of animal anatomy, gained through dissection and constant sketching from life, was fundamental to her style. This allowed her to depict animals in motion with convincing accuracy, capturing the tension of muscles and the structure of bone beneath the skin. This scientific approach differentiated her work, lending it an authority and power that impressed viewers accustomed to more stylized or anthropomorphic animal portrayals.

While primarily a Realist, her work occasionally shows influences from Romanticism, particularly in the dramatic energy of pieces like The Horse Fair, recalling the dynamic animal paintings of artists like Eugène Delacroix. However, her core commitment remained fidelity to nature. She drew inspiration from seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish masters, such as Paulus Potter, known for his detailed cattle paintings, admiring their technical skill and direct observation of rural life. She shared this affinity for rural subjects and animal depiction with Barbizon School painters like Constant Troyon, though her style remained generally more polished and detailed than theirs.

International Acclaim and Royal Patronage

The phenomenal success of The Horse Fair propelled Rosa Bonheur to international stardom. Following its exhibition at the Paris Salon, the painting toured Great Britain in 1855, where it was met with immense enthusiasm. Queen Victoria herself requested a private viewing at Windsor Castle and expressed great admiration for both the painting and the artist. This royal endorsement significantly boosted Bonheur's reputation in Britain, a nation with a strong tradition of animal painting, exemplified by artists like Sir Edwin Landseer.

The painting continued its journey, crossing the Atlantic to tour the United States, where it also garnered widespread acclaim. Its fame was further amplified through engravings and reproductions, making it one of the most recognizable images of the nineteenth century. The international art dealer Ernest Gambart played a crucial role in promoting Bonheur's work abroad, particularly in Britain, ensuring her financial success and solidifying her global reputation. Eventually, the original large version of The Horse Fair was purchased by the American railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who donated it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1887, where it remains a major attraction.

Bonheur became one of the few artists of her time, and certainly one of the few women, to achieve significant financial independence solely through her art. Her works commanded high prices, and she received numerous commissions from wealthy patrons in France, Britain, and America. This success allowed her to live and work on her own terms, further enhancing her image as a remarkably independent figure.

Her achievements were formally recognized in France as well. In 1865, Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoleon III, bestowed upon her the Cross of the Legion of Honour, making Bonheur the first woman artist to receive this prestigious award. She was later promoted to Officer of the order in 1894. These accolades underscored her exceptional status in the art world and served as powerful symbols of recognition for female artists.

A Life Less Ordinary: Independence and Relationships

Rosa Bonheur's life was as unconventional as her professional methods. Fiercely independent, she defied nineteenth-century expectations of femininity in nearly every aspect of her existence. Beyond her practical adoption of male attire for work, she kept her hair short, smoked cigarettes, and projected an air of confidence and self-reliance that was unusual for women of her time. She never married, choosing instead a life dedicated to her art and shared with female companions.

For over forty years, from around 1849 until Nathalie Micas's death in 1889, Bonheur lived and worked alongside Nathalie Micas. Micas, whom Bonheur met as a child and whose mother cared for Bonheur after her own mother's death, became her lifelong companion and partner. They shared a home, managed household affairs together, and Micas often assisted Bonheur in preparing canvases and managing the studio. Their relationship, while perhaps not overtly defined in modern terms, was clearly one of deep mutual affection, partnership, and commitment.

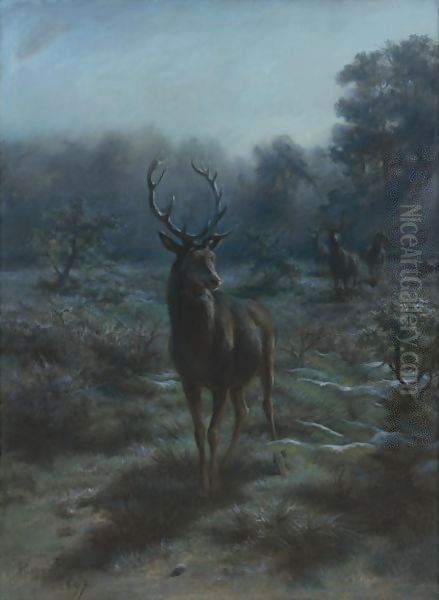

The Bonheur-Micas household was unconventional in other ways too. Bonheur's passion for animals extended to keeping a veritable menagerie at her country estate, the Château de By, near the Forest of Fontainebleau, which she purchased in 1860. Her collection included horses, sheep, cattle, deer, goats, birds, and even more exotic creatures like lions and monkeys, all serving as models for her paintings. This rural retreat became her sanctuary, allowing her to immerse herself in the natural world she loved to paint.

After Nathalie Micas's death, Bonheur formed a close relationship with the American painter Anna Elizabeth Klumpke. Klumpke initially sought out the aging Bonheur to paint her portrait in 1898. A deep bond formed between the two women, and Klumpke moved into the Château de By, becoming Bonheur's companion, studio assistant, and designated heir. Klumpke later wrote an admiring biography of Bonheur, providing invaluable insights into her life and work, and played a crucial role in preserving her legacy after Bonheur's death in 1899. Bonheur's choices reflected the Saint-Simonian ideals of equality and freedom she had absorbed from her father, living life on her own terms.

The Château de By and Later Years

In 1860, flush with the success of The Horse Fair and subsequent works, Rosa Bonheur purchased the Château de By, a country estate located in Thomery, on the edge of the Forest of Fontainebleau. This move provided her with the space and seclusion she desired to pursue her art and live surrounded by her beloved animals. The château became her home, studio, and personal zoo for the remainder of her life.

The estate allowed her to create an ideal working environment. She maintained extensive stables, pastures, and enclosures for her diverse collection of animal models. Her large studio, purpose-built on the grounds, was filled with canvases, easels, anatomical specimens, and sketches. Here, she continued to work prolifically, producing numerous paintings of animals, both domestic and wild, often set against the backdrop of the Fontainebleau forest, a landscape favored by the Barbizon painters like Théodore Rousseau and Camille Corot.

Life at By was relatively secluded but not isolated. Bonheur maintained correspondence with artists, dealers, and admirers, and occasionally received visitors, including prominent figures like Empress Eugénie and Buffalo Bill Cody (whose portrait she painted during his Wild West show's visit to Paris in 1889). She continued to exhibit her work, though less frequently at the Paris Salon in later years, preferring to sell through dealers like Gambart and later Georges Petit.

Her later work maintained her characteristic realism and technical skill, though some critics noted a slight softening of style. She explored new subjects, including the American bison and wild horses inspired by Buffalo Bill's show. Her partnership with Nathalie Micas remained central to her life at By until Micas's death in 1889, a loss that deeply affected Bonheur. The arrival of Anna Klumpke nearly a decade later brought renewed companionship and support in her final years. Rosa Bonheur died at the Château de By on May 25, 1899, at the age of 77, leaving behind a significant body of work and a formidable legacy.

Connections and Contemporaries

Rosa Bonheur operated within a vibrant nineteenth-century art world, interacting with, influencing, and being compared to numerous contemporaries. Her primary artistic relationship was with her family: her father Raymond Bonheur was her teacher, and her siblings Auguste Bonheur (painter), Isidore Bonheur (sculptor), and Juliette Bonheur (painter) were also professional artists, creating an unusually artistic family unit.

As a leading Realist, she shared thematic ground with Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, though her focus remained steadfastly on animals rather than the human peasant life often central to their work. Her detailed style differed from Courbet's bolder application of paint. She was associated geographically and thematically with the Barbizon School painters (Théodore Rousseau, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Constant Troyon), who also worked near Fontainebleau and emphasized direct observation of nature, although she was never formally part of their group. Troyon, in particular, was another prominent animal painter.

Her international fame brought comparisons, not always favorable, with Britain's premier animal painter, Sir Edwin Landseer. Some critics accused her of imitating his style, particularly his occasional tendency towards anthropomorphism, though Bonheur generally maintained a more objective stance. Her success undoubtedly paved the way for later women artists seeking professional careers, including the Impressionists Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, even if their artistic styles diverged significantly.

She maintained professional relationships with dealers like Ernest Gambart and Georges Petit, crucial for her international market. Her later life saw direct collaboration and companionship with Anna Klumpke, who became her biographer. She also collaborated on at least one occasion with the painter Consuelo Fould. While admired by many, her singular focus and immense success likely created a degree of professional distance, placing her in a unique category rather than within a specific collaborative circle for much of her mature career. Her influence stemmed more from her example and her celebrated works than from direct mentorship outside her family school.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Rosa Bonheur's legacy is multifaceted. Artistically, she is remembered as the preeminent female painter of the nineteenth century and one of the foremost animal painters (animaliers) in Western art history. Her commitment to Realism, underpinned by rigorous anatomical study and direct observation, set a standard for animal depiction. Works like Ploughing in the Nivernais and especially The Horse Fair remain iconic examples of nineteenth-century French painting, celebrated for their technical brilliance, dynamic composition, and powerful rendering of animal life.

Her impact extends far beyond the canvas. In an era when women faced significant barriers in professional life, Bonheur achieved extraordinary commercial success and critical acclaim on an international scale. Her financial independence, professional determination, and prestigious accolades, particularly being the first woman artist awarded the Legion of Honour, served as powerful inspiration for subsequent generations of women artists striving for recognition and equality.

Her unconventional personal life – her lifelong partnerships with women, her adoption of male attire, her independent lifestyle – positioned her as a proto-feminist icon. She challenged gender norms not through overt political action but through the way she lived and worked, demonstrating that a woman could achieve greatness in a male-dominated field without conforming to societal expectations. This aspect of her life has received increasing attention in recent decades, adding another layer to her historical significance.

Today, her works are held in major museums worldwide, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the National Gallery in London. The Château de By, preserved largely as she left it thanks to Anna Klumpke, now functions as a museum dedicated to her life and work, offering a unique glimpse into her world. Rosa Bonheur remains a pivotal figure, admired for her artistic mastery, her pioneering spirit, and her enduring challenge to convention.

Conclusion

Rosa Bonheur carved out an exceptional place in art history through sheer talent, unwavering dedication, and a refusal to be constrained by the limitations imposed on women in her time. From her early training under her artist father to her meticulous studies in Parisian markets and abattoirs, she honed a skill for animal depiction that was unparalleled. Her masterpieces, particularly the globally celebrated The Horse Fair, showcased her profound understanding of animal anatomy and her ability to capture their vitality within the framework of Realism. Her international success and prestigious awards broke barriers, demonstrating that artistic genius knows no gender. Equally significant was her independent life, lived on her own terms, which continues to resonate as a powerful example of female autonomy. Rosa Bonheur remains not just a painter of animals, but a towering figure whose art and life story continue to inspire and command respect.