Robert Walker, an English painter of considerable note, carved a unique niche for himself during one of England's most tumultuous periods, the mid-17th century. Flourishing from the 1640s until his death around 1658, Walker is primarily remembered as the foremost portraitist of the Parliamentarian leaders, most notably Oliver Cromwell. His work provides an invaluable visual record of the men who reshaped the political and religious landscape of England, offering a sober counterpoint to the flamboyant courtly style established by Sir Anthony van Dyck. While details of his early life remain somewhat obscure, his artistic output firmly places him as a significant figure in the trajectory of English art, bridging the era of Van Dyck with the subsequent rise of painters like Sir Peter Lely.

The Artistic Landscape of Early 17th-Century England

To understand Robert Walker's emergence, one must consider the artistic environment he was born into, likely around 1600-1607. English art at the turn of the 17th century was still heavily reliant on foreign talent. The Tudor and early Stuart courts had patronized artists from the continent, such as Hans Holbein the Younger in the previous century. In Walker's formative years, painters like Daniel Mytens, a Dutchman, served as court painter to James I and Charles I, producing dignified but somewhat stiff representations of royalty and the aristocracy.

Another prominent figure was Cornelius Johnson (Cornelis Janssens van Ceulen), born in London to Flemish or Dutch parents. Johnson's portraits were known for their sensitivity and meticulous detail, capturing a certain introspection in his sitters. These artists, along with a native tradition of miniature painting, exemplified by masters like Nicholas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver, constituted the primary artistic influences before a seismic shift occurred.

The arrival of Anthony van Dyck in England in 1632, at the invitation of King Charles I, revolutionized English portraiture. Van Dyck, a former star pupil of Peter Paul Rubens, brought with him a new level of sophistication, elegance, and psychological depth. His portraits of Charles I and the Caroline court set an unparalleled standard, characterized by fluid brushwork, rich colours, dynamic poses, and an air of effortless aristocracy. Van Dyck's influence was so profound that virtually every aspiring portraitist in England for the next generation would, in some way, respond to his style. Robert Walker was no exception.

Walker's Emergence and the Van Dyckian Influence

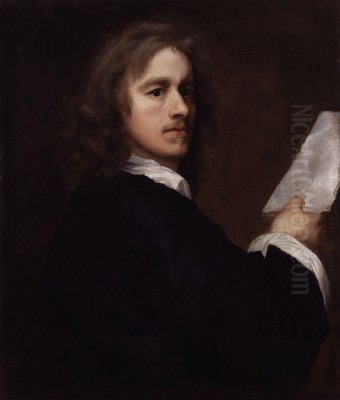

The precise details of Robert Walker's training are not definitively known. It is widely accepted, however, that he was deeply influenced by the work of Van Dyck. He may have had access to Van Dyck's studio or, at the very least, ample opportunity to study his paintings, which were widely disseminated and admired. Walker's own self-portraits, notably one where he holds a drawing of Mercury and another depicting him with a statue, clearly echo Van Dyckian compositions and motifs, particularly Van Dyck's self-portrait with a sunflower.

Walker's assimilation of the Van Dyckian style was not mere imitation. While he adopted the elegance of pose and the sophisticated handling of fabrics, his portraits often possess a more reserved and introspective quality. This might reflect his own temperament, the character of his sitters, or the prevailing Puritan austerity that gained prominence during the English Civil War. His palette, while competent, sometimes lacked the vibrant richness of Van Dyck, leaning towards more muted and sombre tones, which suited the grave demeanor of many Parliamentarian figures.

Unlike William Dobson, another highly talented English painter who was a staunch Royalist and whose work often conveyed a more robust and direct character, Walker's approach was generally more restrained. Dobson, often considered one of the first truly great native English painters alongside Walker, captured the anxieties and defiant spirit of the Royalist cause before his early death in 1646. Walker, by contrast, became the visual chronicler of the opposing faction.

Principal Painter to the Parliament

The outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642 dramatically altered the landscape of artistic patronage. With the King and his court displaced, and many Royalist patrons engaged in conflict or exile, artists had to seek new sources of support. Robert Walker successfully navigated this changing environment, aligning himself with the Parliamentarian cause. He became the go-to artist for portraits of leading figures in the Parliament, the New Model Army, and later, the Protectorate.

His most famous and historically significant commissions were his portraits of Oliver Cromwell. Cromwell, initially a relatively obscure Member of Parliament, rose to become Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Walker painted Cromwell on several occasions, and these images have largely defined Cromwell's visual identity for posterity. One of the most well-known versions, now in the National Portrait Gallery, London, shows Cromwell in armour, holding a baton, a man of authority and resolve.

An oft-repeated anecdote, though its veracity is debated, claims that Cromwell instructed Walker to paint him "warts and all," or more precisely, "remark all these roughnesses, pimples, warts, and everything as you see me, otherwise I will never pay a farthing for it." Whether true or not, the sentiment reflects a desire for unvarnished realism, a departure from the idealized portrayals often favoured by royalty. Walker's portraits of Cromwell convey a sense of gravitas and inner strength, without excessive flattery. They are powerful character studies of a complex and formidable leader.

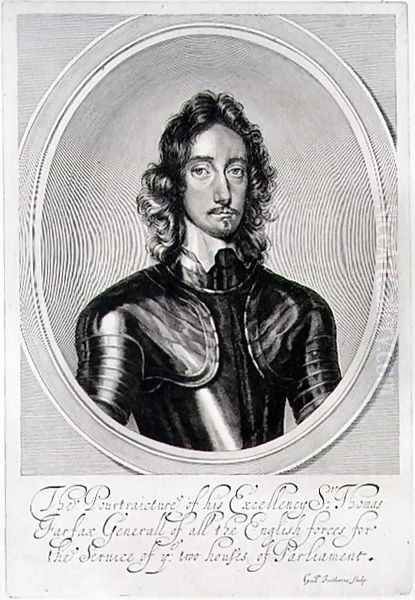

Beyond Cromwell, Walker painted many other key Parliamentarian and military figures. These included Major-General John Lambert, a prominent soldier and politician; Henry Ireton, Cromwell's son-in-law and a significant figure in the New Model Army; Charles Fleetwood, another of Cromwell's sons-in-law and a military commander; and Richard Keble, a lawyer and Commissioner of the Great Seal. He also painted figures like John Evelyn, the diarist, though some attributions remain subjects of scholarly discussion. These portraits, collectively, form an invaluable gallery of the men who governed England during the Interregnum.

Stylistic Characteristics and Notable Works

Robert Walker's style, while rooted in the Van Dyckian tradition, developed its own distinct characteristics. His compositions were often straightforward, focusing on the sitter's face and upper body. He paid careful attention to the rendering of armour, which featured prominently in his portraits of military leaders, capturing its metallic sheen and intricate details. His depiction of fabrics, such as lace collars and cuffs, was also skilled, though perhaps less flamboyant than Van Dyck's.

His figures typically exude a sense of seriousness and purpose. There is little of the leisurely elegance or aristocratic nonchalance found in Van Dyck's court portraits. Instead, Walker's sitters often appear contemplative, resolute, or burdened by responsibility, reflecting the sober and often perilous times in which they lived. This psychological insight, though perhaps less overtly dramatic than that of some of his contemporaries, lends a quiet power to his work.

One of his most compelling self-portraits, sometimes referred to as "Robert Walker, an artist, said to be a self-portrait" (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford), shows him holding a statuette of Mercury, the messenger god and patron of the arts. This work, with its classical allusion and confident pose, demonstrates Walker's ambition and his understanding of the artistic conventions of his time. It is a clear homage to Van Dyck's self-portraits, particularly the one with the sunflower, indicating Walker's aspiration to be seen in a similar light as a master of his craft.

Another notable work often attributed to Walker is the "Portrait of an Unknown Man" (c. 1650, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.), which showcases his ability to capture a sense of thoughtful melancholy. The sitter, dressed in black with a simple white collar, gazes directly at the viewer with a searching expression. The restrained palette and focus on the sitter's psychology are characteristic of Walker's mature style.

His group portraits, though less common, also demonstrate his skill. For instance, his depiction of "The Officers of the London Trained Bands" (though attribution and specific subject matter can be complex for such works) would have required considerable organizational skill in composition.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu of the Interregnum

During the Interregnum (1649-1660), the artistic scene in England was somewhat subdued compared to the lavish patronage of Charles I's reign. However, portraiture remained in demand. Robert Walker was arguably the leading figure in this field, especially for those aligned with the new regime.

Peter Lely (originally Pieter van der Faes), a Dutch painter, had arrived in England in the early 1640s. During the Interregnum, Lely also painted portraits of Parliamentarian figures, including Cromwell, and began to build a successful practice. Lely's style, also influenced by Van Dyck, was perhaps more polished and adaptable than Walker's. After the Restoration in 1660, Lely would succeed Van Dyck as the dominant force in English portraiture, becoming court painter to Charles II and defining the visual style of the Restoration era with his sensuous and elegant portraits. Walker and Lely were, for a time, the two most prominent portraitists working in London.

Other painters active during this period included Gerard Soest, another artist of Dutch origin, who developed a strong, realistic style, and Isaac Fuller, known for his rather more flamboyant and sometimes eccentric history paintings and portraits. The tradition of miniature painting continued with artists like Samuel Cooper, who produced powerful and intimate likenesses of Cromwell and other leading figures, often considered among the greatest English miniaturists. Cooper's work, in its own small scale, paralleled Walker's in capturing the essence of the Parliamentarian leadership.

The artistic connections were not limited to England. The influence of Dutch art, beyond Van Dyck (who was Flemish), was also palpable. The realism and psychological depth found in the works of Dutch masters like Rembrandt van Rijn and Frans Hals, while perhaps not a direct, traceable influence on Walker, were part of a broader European trend towards more naturalistic and characterful portraiture.

Later Years and Death

Information about Robert Walker's later years is as sparse as that of his early life. He is believed to have died around 1658, just before the collapse of the Protectorate and the subsequent Restoration of the monarchy. His death occurred at a pivotal moment, as the political tides were beginning to turn. Had he lived into the Restoration, his close association with the Cromwellian regime might have proven problematic for his career, although Lely managed the transition successfully.

His will, if one was made and survived, might have shed more light on his personal circumstances, family, and studio practice, but such details remain elusive. He seems to have maintained a successful practice in London, likely around the Covent Garden area, which was a popular district for artists.

The exact date of his death is often cited as November 1658. This timing meant he did not witness the return of Charles II in 1660, an event that ushered in a new era of artistic patronage and taste, largely dominated by the aforementioned Peter Lely and, later, Sir Godfrey Kneller.

Legacy and Art Historical Evaluation

Robert Walker's legacy is primarily tied to his role as the chief painter of the Parliamentarian side during the English Civil War and Interregnum. His portraits of Oliver Cromwell are iconic and have profoundly shaped our visual understanding of this crucial figure in English history. They are not merely likenesses but potent symbols of a revolutionary era.

While often seen as working in the shadow of Van Dyck, Walker was more than a mere copyist. He adapted the Van Dyckian formula to suit a different clientele and a different ideological climate. His portraits possess a sobriety and directness that reflect the Puritan ethos of many of his sitters. He demonstrated that the grand manner of Van Dyck could be modified to convey republican virtue as effectively as royal splendor.

Compared to William Dobson, Walker's style might seem less overtly vigorous or innovative. Dobson's tragically short career produced works of remarkable power and originality. However, Walker's sustained output over a longer period, and his consistent ability to capture the character of his sitters, secure his place as a significant artist. He provided a vital visual record of a period when England was undergoing profound transformation.

His influence on subsequent English portraiture is perhaps less direct than that of Lely or Kneller, who established a new courtly style after the Restoration. However, Walker contributed to the continuity of a native English school of portraiture, demonstrating that English artists could achieve a high level of competence and psychological insight. His work stands as a testament to the resilience of artistic production even in times of civil strife and political upheaval.

Art historians today recognize Walker for his historical importance and his artistic merit. His paintings are essential documents for understanding the personalities and the visual culture of the English Republic. While he may not have reached the dazzling heights of Van Dyck, or possessed the raw energy of Dobson, Robert Walker was a skilled and insightful portraitist who faithfully served his patrons and left behind a compelling visual account of a unique chapter in English history. His work continues to be studied for its artistic qualities and its invaluable contribution to the iconography of power and personality in 17th-century England. He remains a key figure for anyone studying the art of the period, standing alongside other notable English-born or English-active painters such as George Gower from an earlier generation, or later figures like Jonathan Richardson and Thomas Hudson who paved the way for the golden age of British painting with Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. Walker's particular contribution was to define the look of a revolutionary government, a task few artists are called upon to undertake.