Victor Higgins stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of early 20th-century American art. Born William Victor Higgins on June 28, 1884, in Shelbyville, Indiana, he emerged from a rural farming background to become one of the most respected and innovative painters of his generation. His journey took him from the burgeoning art scene of Chicago to the hallowed academies of Europe, and ultimately to the sun-drenched, culturally rich environment of Taos, New Mexico. There, he became a founding member of the influential Taos Society of Artists, contributing significantly to a uniquely American artistic vernacular that blended keen observation with modernist sensibilities. Higgins's legacy is one of technical mastery, profound empathy for his subjects, and a relentless pursuit of an authentic artistic voice that captured the spirit of his time and place. His work, characterized by its vibrant color, dynamic compositions, and deep understanding of light, continues to resonate with audiences and scholars alike, securing his position as a master of American painting.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Victor Higgins's artistic journey began in the agricultural heartland of Indiana. Raised on a farm, his early life was steeped in the rhythms of nature and the realities of rural existence, experiences that would subtly inform his later depictions of landscape and human connection to the land. From a young age, Higgins displayed a clear proclivity for drawing and painting, an interest that his family, particularly his father, astutely recognized and supported. This encouragement was crucial, allowing the young artist to nurture his burgeoning talent.

At the tender age of fifteen, driven by an undeniable artistic calling, Higgins made the significant move to Chicago. This bustling metropolis, rapidly establishing itself as a cultural center, offered opportunities far beyond what rural Indiana could provide. In Chicago, he embarked on formal art training, enrolling first at the prestigious Art Institute of Chicago and later at the Academy of Fine Arts. These institutions provided him with a solid foundation in academic drawing and painting techniques, exposing him to a wide range of artistic theories and practices. It was during this formative period in Chicago that he forged important early connections with fellow artists, including E. Martin Hennings and Uther Carter, friendships that would provide camaraderie and intellectual exchange as they navigated their artistic paths.

European Sojourn: Broadening Horizons

Following his foundational studies in Chicago, Higgins, like many ambitious American artists of his era, sought to further refine his skills and broaden his artistic perspective by traveling to Europe. This period of international study was considered an essential rite of passage, offering exposure to the masterpieces of the past and the vibrant contemporary art scenes of the continent. Higgins immersed himself in the artistic milie popolazione of Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world. He studied under several notable figures, including the influential American expatriate Robert Henri, whose emphasis on capturing the vitality of modern life and developing a distinctly American art resonated deeply with Higgins.

In Paris, he also received instruction from respected French academicians René Menard and Lucien Simon, who would have imparted a sophisticated understanding of composition, color, and painterly technique. His European education was not confined to Paris; Higgins also spent time in Munich, studying with Hans von Hayek. This diverse tutelage exposed him to various artistic philosophies, from the lingering traditions of academic painting to the fresh currents of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and the nascent stirrings of modernism. He diligently absorbed these influences, particularly the aesthetic theories of progressive painters like Robert Henri and his circle, known as "The Eight" or the Ashcan School, which included artists such as John Sloan, George Luks, and William Glackens. Higgins was determined to synthesize these European lessons with his American roots to forge a style that was both technically accomplished and uniquely his own, reflecting an authentic American experience.

The Allure of Taos: A New Artistic Frontier

The year 1913 marked a pivotal turning point in Victor Higgins's life and career. At the behest of Carter H. Harrison Jr., the art-collecting mayor of Chicago and a significant patron of the arts, Higgins was encouraged—and likely financially supported—to travel to Taos, New Mexico. Harrison, who had previously facilitated similar journeys for other Chicago artists like E. Martin Hennings, recognized the unique artistic potential of the remote New Mexico village. For Higgins, this was more than just a trip; it was a profound encounter with a landscape and culture that would captivate him for the rest of his life.

Upon arriving in Taos, Higgins was immediately struck by the dramatic beauty of the high desert environment: the crystalline light, the stark, sculptural forms of the mountains, the vibrant colors of the earth, and the distinctive adobe architecture. Equally compelling was the rich cultural tapestry of the region, particularly the ancient, enduring traditions of the Taos Pueblo Indians and the Hispanic communities. This environment offered a wealth of fresh subject matter, a world away from the urban scenes of Chicago or the cultivated landscapes of Europe. Higgins quickly established himself in Taos, recognizing it as a place where he could truly develop his artistic vision. The raw, untamed beauty and the spiritual resonance of the land provided fertile ground for an artist seeking to create a distinctly American form of expression.

The Taos Society of Artists: A Collective Vision

Shortly after his arrival, Victor Higgins became an integral part of the burgeoning art colony in Taos. In 1915, he, along with Ernest L. Blumenschein, Oscar E. Berninghaus, E. Irving Couse, Joseph Henry Sharp, and W. Herbert Dunton, formally established the Taos Society of Artists. This collective was born out of a shared fascination with the region and a desire to create and promote art that captured its unique character. The Society aimed to send traveling exhibitions of their work across the United States, thereby introducing a wider American public to the landscapes and peoples of the Southwest.

Higgins was the youngest of the founding members, bringing a fresh perspective and a burgeoning modernist sensibility to the group. While many of the early Taos painters focused on romanticized or ethnographic depictions of Native American life, Higgins, though initially engaging with these subjects, soon began to explore more personal and experimental approaches. His early Taos works often featured portraits of Pueblo individuals and scenes of their daily lives, rendered with sensitivity and a keen eye for detail. However, even in these earlier pieces, one can discern a sophisticated understanding of form and color that hinted at his future stylistic developments. His involvement with the Taos Society of Artists provided him with a supportive community and a platform for his work, while his evolving style contributed to the group's dynamic and diverse artistic output. Other artists who became members later, such as Walter Ufer and E. Martin Hennings (who joined after Higgins's encouragement), further enriched the Society's contributions.

Stylistic Evolution: From Realism to Modernist Abstraction

Victor Higgins's artistic journey in Taos was one of continuous evolution and experimentation. While his initial works in New Mexico were grounded in a strong realist tradition, reflecting his academic training and the influence of painters like Robert Henri, he increasingly pushed the boundaries of representation. He was deeply affected by the principles of modernism filtering in from Europe, particularly the work of Post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne, and later, the more abstract tendencies of artists such as Marsden Hartley, who also spent time in New Mexico.

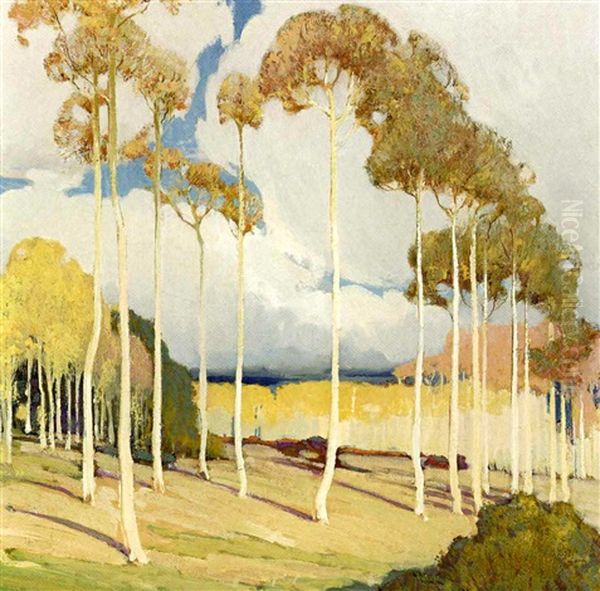

Higgins began to simplify forms, flatten perspectives, and employ color in a more subjective and expressive manner. His compositions became more dynamic and structured, often emphasizing geometric underpinnings and rhythmic patterns. This shift is evident in his landscapes, where he moved beyond mere depiction to capture the essential spirit and abstract qualities of the New Mexico terrain. Mountains, clouds, and adobe structures were distilled into powerful, almost monumental forms, imbued with a sense of timelessness. His still lifes, often featuring local pottery, fruits, and textiles, became vehicles for exploring complex arrangements of color, texture, and form, echoing the formal concerns of European modernists like Georges Braque or even early Pablo Picasso, though Higgins never fully embraced Cubism. This transition saw him move from detailed portrayals of Indigenous subjects and genre scenes towards more experimental landscapes, still lifes, and eventually, nudes, showcasing his versatility and his commitment to artistic growth.

Prominent Themes and Subject Matter

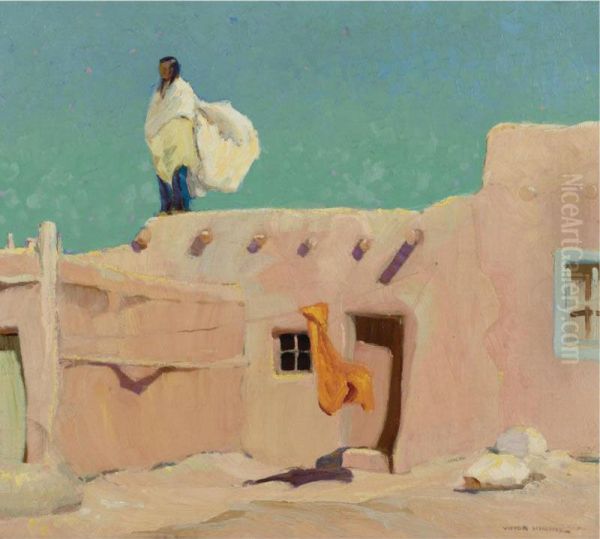

Throughout his career in Taos, Victor Higgins explored a range of themes and subjects that reflected both the unique character of his adopted home and his evolving artistic concerns. The indigenous people of Taos Pueblo were an early and significant focus. Works like Pueblo Woman of Taos or Juan Domingo and the Bread Jar demonstrate his ability to capture the dignity and quiet strength of his subjects, often portraying them engaged in daily activities or in moments of contemplation. These paintings are characterized by their rich color, solid forms, and empathetic portrayal, avoiding mere exoticism.

The New Mexico landscape was an enduring passion for Higgins. He painted its mountains, mesas, and vast skies in all seasons and at all times of day, constantly experimenting with ways to convey its unique light and atmosphere. Paintings such as Winter Funeral reveal his capacity for capturing the solemn beauty and emotional resonance of the land and its human dramas. His landscapes often possess a strong structural quality, with simplified masses and bold color harmonies that move towards abstraction while retaining a powerful sense of place. Later in his career, still life became an important genre for Higgins. These compositions, often featuring Southwestern pottery, flowers, and fruit, allowed him to experiment freely with color, form, and texture, creating arrangements that were both visually rich and formally sophisticated. He also produced a notable series of nudes, often placing the figure within a landscape or an abstracted interior, exploring the human form with a modernist sensibility.

Masterful Techniques and Artistic Characteristics

Victor Higgins was renowned for his exceptional technical skill and a sophisticated artistic approach that blended traditional craftsmanship with modernist innovation. His draftsmanship was strong and assured, providing a solid foundation for his paintings, whether they were detailed portraits or more abstracted landscapes. He possessed a remarkable sensitivity to color, employing a palette that could range from subtle, earthy tones to vibrant, high-keyed hues. His ability to capture the unique quality of light in New Mexico – its clarity, intensity, and transformative effects – was a hallmark of his work.

Higgins's brushwork was varied and expressive, capable of rendering smooth, subtle gradations as well as bold, textural passages. He often built up his surfaces with layers of paint, creating a rich, luminous quality. His compositions were carefully considered, often employing dynamic diagonals, strong geometric structures, and a sophisticated sense of balance. He was a master of simplifying complex scenes into their essential forms, creating images that were both visually striking and emotionally resonant. Even as he embraced modernist principles of abstraction and formal experimentation, Higgins never abandoned his commitment to keen observation and a deep connection to his subject matter. This ability to synthesize the analytical approach of modernism with a profound humanism is a key characteristic of his most powerful work. His paintings often evoke a sense of monumentality and timelessness, whether depicting a mountain range or a simple still life.

Notable Works: A Glimpse into Higgins's Vision

Several paintings stand out as iconic representations of Victor Higgins's artistic achievements. Taos Pueblo Woman (often referred to by various similar titles depicting women from the Pueblo) is a recurring theme, and these works are celebrated for their dignified portrayal of Indigenous figures, rendered with rich color and strong, sculptural forms. These paintings capture a sense of timelessness and cultural endurance.

Winter Funeral (c. 1931) is one of his most poignant and well-known works. It depicts a small group of mourners on a snow-covered hillside, with the stark white of the snow contrasting with the dark figures and the somber tones of the distant mountains. The painting masterfully conveys a sense of grief, community, and the harsh beauty of the winter landscape, showcasing Higgins's ability to blend narrative with powerful formal design.

Juan Domingo and the Bread Jar (c. 1918) is an early Taos masterpiece, portraying a Pueblo man with a large, decorated pottery jar. The painting is notable for its strong composition, rich textures, and the sensitive rendering of the subject's character. It reflects the influence of Robert Henri in its directness and focus on the human element.

His still lifes, such as Still Life with Two Pears and a Pot or Indian Paint Brush and Pottery, demonstrate his mastery of the genre. These works are often characterized by their vibrant colors, complex arrangements, and a focus on the interplay of light, texture, and form. They reveal his deep appreciation for the aesthetic qualities of everyday objects and his sophisticated understanding of modernist compositional principles.

Landscapes like Canyon Drive, Taos or New Mexico Skies showcase his ability to capture the grandeur and unique atmosphere of the Southwestern environment. He often simplified the landscape into bold, abstract shapes and used color to convey mood and light, pushing towards a more modern interpretation of the genre. Canyon of Dunes, mentioned in some accounts, likely refers to his skill in depicting the unique geological formations and light play of the region, possibly in or around Santa Fe or Taos. These works, and many others, solidify his reputation as an artist who could imbue his subjects with both visual power and emotional depth.

Recognition, Awards, and Enduring Influence

Victor Higgins's talent did not go unrecognized during his lifetime. He received numerous prestigious awards, underscoring his standing in the American art world. Among these were the Logan Prize from the Art Institute of Chicago, a significant honor that recognized excellence in American art. He also received the Altman Prize from the National Academy of Design in New York, further cementing his national reputation. The Palette and Chisel Club of Chicago, an important artists' organization, also honored him with a gold medal.

His work was widely exhibited in major museums and galleries across the United States, including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. He was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design in 1921 and a full Academician in 1935. Beyond his painting, Higgins also contributed as a teacher, holding positions at the Art Institute of Chicago and later offering instruction in Taos, influencing a younger generation of artists. His paintings were sought after by private collectors and public institutions, and today, his works are held in the permanent collections of many leading American museums, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the National Gallery of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art, New York, as well as numerous regional museums specializing in Western American art.

Later Years and Lasting Legacy

Victor Higgins continued to live and work in Taos, New Mexico, for the remainder of his life, remaining a vital and evolving artistic presence. He maintained a deep connection to the landscape and its people, constantly finding new inspiration in the familiar surroundings. His later works often showed an increased tendency towards abstraction and a more introspective quality, yet they never lost their grounding in the visual realities of the world around him. He explored themes of spirituality and the elemental forces of nature with growing depth and sophistication.

His dedication to his craft was unwavering, and he produced a significant body of work that spanned several decades. Victor Higgins passed away on August 23, 1949, in Taos. His death was considered a significant loss to the American art community and marked, in some ways, the end of an era for the Taos art colony, as many of the original founding members of the Taos Society of Artists had by then passed away or moved on.

The legacy of Victor Higgins is multifaceted. He was a master technician, a brilliant colorist, and a compositional innovator. He played a crucial role in the development of the Taos art colony and the broader movement of American modernism. His ability to synthesize the influences of European modernism with a distinctly American sensibility, rooted in the landscapes and cultures of the Southwest, resulted in a body of work that is both timeless and deeply evocative of its specific time and place. He is remembered as one of the most important painters of the American West, an artist who transcended regionalism to create works of universal appeal and enduring artistic significance. His paintings continue to be studied, admired, and celebrated for their beauty, their emotional depth, and their unique contribution to the story of American art.