Oscar Bluemner stands as a fascinating and pivotal figure in the story of American modern art. Born in Germany and trained initially as an architect, he transformed himself into one of the most distinctive and emotionally resonant painters of the early 20th century in the United States. His journey from the structured world of building design to the expressive realm of vibrant, abstracted landscapes is a tale of artistic conviction, personal struggle, and a profound engagement with the power of color. Though not widely celebrated during his lifetime, Bluemner's unique vision and his contribution to the development of modernism are now recognized as essential components of American art history.

From German Roots to American Shores: Early Life and Architectural Pursuits

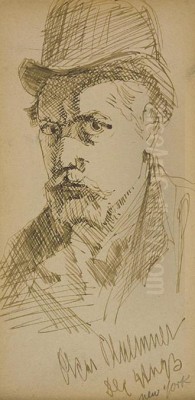

Friedrich Julius Oskar Blümner, later known as Oscar Bluemner, was born in Prenzlau, Germany (now Prężnów, Poland), in 1867. His path towards art began early, with formal art education commencing around the age of nine. His academic pursuits led him to the prestigious Königliche Technische Hochschule (Royal Technical College) in Berlin, where he studied architecture and painting from 1886 to 1892. His talent was recognized early on, earning him a Royal Medal for his architectural work.

Despite this early success and training, Bluemner found the prospects for consistent patronage or fulfilling work in Germany lacking. Seeking greater opportunities, he made the significant decision to immigrate to the United States in 1892. He initially settled in Chicago, hoping to establish himself as an architect during a period of significant urban growth, coinciding with the World's Columbian Exposition. However, success proved elusive in the competitive Chicago environment.

By 1900, Bluemner had relocated to New York City, another burgeoning metropolis offering potential architectural commissions. He attempted to establish his own architectural practice, but financial difficulties hampered these efforts. A notable, yet ultimately frustrating, project from this period was his design work for the Bronx Borough Courthouse. Bluemner collaborated with architect Michael J. Garvin on the designs, but a dispute arose when Garvin allegedly took sole credit for the work. This led to a protracted legal battle, which Bluemner eventually won, but the experience soured him on the architectural profession in America, which he found increasingly conservative and fraught with ethical compromises.

The Transformative Encounter: Stieglitz and the Shift to Painting

The year 1908 marked a crucial turning point in Bluemner's life and career. He met Alfred Stieglitz, the influential photographer, publisher, and gallerist who was a central figure in promoting modern art in America. Stieglitz operated the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession at 291 Fifth Avenue, commonly known as "291," which became a vital hub for the American avant-garde. Stieglitz recognized Bluemner's artistic potential and became a key supporter and mentor.

Through Stieglitz and the circle of artists associated with 291 – including painters like Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and John Marin, and later Georgia O'Keeffe – Bluemner was exposed more deeply to the currents of European and American modernism. Stieglitz encouraged Bluemner's growing inclination towards painting, providing not just intellectual stimulation but also practical support. This encounter solidified Bluemner's decision to largely abandon architecture and dedicate himself fully to painting around 1910-1912. His dissatisfaction with the architectural field, combined with the inspiration found within the Stieglitz circle, propelled him onto a new artistic path.

Embracing Modernism: European Influences and the Armory Show

Bluemner's transition to painting coincided with a period of intense artistic ferment on both sides of the Atlantic. He began exhibiting his work, holding a solo show in Berlin in 1912, reconnecting briefly with his European roots. The following year, 1913, was momentous. Bluemner participated in the landmark International Exhibition of Modern Art, better known as the Armory Show, held in New York City. This exhibition famously introduced large American audiences to the radical developments in European art, showcasing works by artists like Marcel Duchamp, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, and Wassily Kandinsky alongside progressive American artists.

Bluemner's inclusion in the Armory Show placed him firmly within the narrative of emerging American modernism. He exhibited alongside contemporaries like Maurice Prendergast, whose mosaic-like Post-Impressionist cityscapes may have initially influenced Bluemner's urban themes, though Bluemner would soon forge a distinct path. The Armory Show was a catalyst, exposing Bluemner to a wider range of modernist idioms and likely reinforcing his own experimental tendencies.

Later in 1913, Bluemner embarked on a significant seven-month trip to Europe. This journey proved deeply influential, allowing him to directly experience the art movements shaping the continent. He absorbed the lessons of Post-Impressionism, particularly the expressive color and brushwork of Vincent van Gogh. He was also drawn to the emotional intensity and spiritual dimensions of German Expressionism, especially the work associated with Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) group, including Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc. The dynamic forms and energy of Italian Futurism also left their mark. This European sojourn was critical in helping Bluemner synthesize various influences and solidify his own artistic direction.

Forging a Unique Vision: Abstraction, Geometry, and the American Landscape

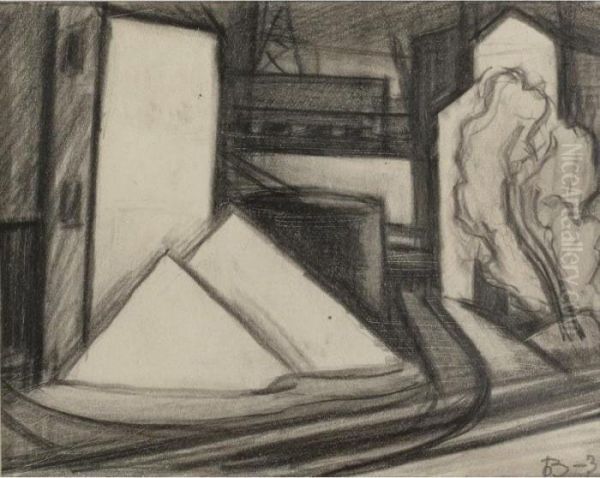

Upon his return to the United States, Bluemner's art underwent a marked transformation. Armed with his European experiences and his architectural background, he began to develop a highly personal style characterized by abstracted landscapes and architectural motifs rendered in bold, often non-naturalistic colors and simplified geometric forms. He sought to capture the underlying structure and emotional essence of his subjects, rather than merely their surface appearance.

His architectural training remained evident in the strong structural compositions of his paintings, but these forms were now imbued with expressive color and dynamic energy. He frequently depicted the industrial landscapes and vernacular architecture of New Jersey and surrounding areas, finding beauty and power in factories, canals, houses, and bridges. Works from this period demonstrate a fascinating fusion of Cubist fragmentation, Expressionist color, and Futurist dynamism, all filtered through his unique sensibility.

Alfred Stieglitz continued to champion Bluemner's work. In 1915, Bluemner had his first American solo exhibition at Stieglitz's 291 gallery, presenting eight landscapes that clearly announced his mature style and established his reputation within the modernist vanguard. He participated in other significant group exhibitions, such as the Forum Exhibition of Modern American Painters in 1916 and a subsequent exhibition at the Anderson Galleries in 1917, further solidifying his presence alongside other key figures of American modernism, including Precisionist painters like Charles Demuth and Charles Sheeler, who also explored industrial and architectural themes, albeit with a cooler, more detached approach.

The Language of Color: A "Prophet" and a "Vermilionaire"

Central to Oscar Bluemner's art and artistic philosophy was his profound engagement with color. He developed complex theories about the psychological and emotional impact of color, meticulously documenting his ideas and observations in his painting diaries. He believed that specific colors could evoke particular feelings and spiritual states, and he used color not just descriptively but symbolically and expressively. His intense, often saturated hues were carefully chosen to convey the mood and inner reality of the scene.

He was particularly drawn to the color red, which he saw as representing powerful forces like masculinity, vitality, struggle, the sun, and even his own alter ego. His fascination with red was so pronounced that he playfully referred to himself as a "Vermilionaire." This deep connection to red is evident in many of his works, where it often dominates or provides a striking contrast, imbuing the paintings with energy and emotional weight. His sophisticated understanding and application of color led some contemporaries and later critics to call him a "prophet of color." He explored the full spectrum, using vibrant blues, greens, yellows, and violets with equal intensity and purpose, creating harmonies and dissonances that charged his landscapes with psychological depth.

Representative Works: Capturing Emotion in Form and Hue

Bluemner's body of work includes numerous powerful paintings that exemplify his unique style.

_Expression of a Silktown (Paterson Centre)_ (1914-1915): This painting depicts the industrial landscape of Paterson, New Jersey, known for its silk mills, with Garret Mountain in the background. It marks a significant step away from realism towards abstraction, using simplified forms and heightened color to convey the energy and structure of the industrial town.

_Red Soil_ (1924): A striking example of Bluemner's intense color use and symbolic intent. The painting features bold, almost fiery reds and oranges depicting the earth, contrasted with other strong colors in the barns and landscape elements. The "copper-colored trenches" and "autumn-leaf-like barns" mentioned in descriptions highlight his metaphorical approach to color and form, likely reflecting his deep personal identification with the color red.

_Violet Tones_ (1934): Painted later in his career, this work showcases his continued experimentation with color to evoke mood. It depicts a street scene in Elizabeth, New Jersey, bathed in rich violet and purple hues, creating an atmosphere of twilight mystery and perhaps melancholy. The vibrant yet somber palette demonstrates his sensitivity to the emotional resonance of specific color ranges.

_Azure_ (1933): As the title suggests, this painting is dominated by shades of blue. It reflects Bluemner's ability to use color to explore different emotional states, in this case likely aiming for a sense of tranquility, vastness, or perhaps a cool detachment, contrasting with the fiery energy of his red-dominated works.

_Twilight_ (undated): Inspired by the landscapes along the Hudson River, this work highlights Bluemner's skill with watercolor, a medium he often used for studies and finished pieces. It likely focuses on the atmospheric effects of changing light, a theme common among landscape painters but interpreted through Bluemner's modernist lens.

_Contrasts (Two Spaces)_ (undated): This title suggests a work focused on formal composition, likely exploring the relationship between architectural or landscape elements through juxtaposition and abstraction, showcasing his roots in architectural design translated into painterly concerns.

These works, among many others, reveal Bluemner's consistent effort to synthesize observation, emotion, and formal structure through the powerful medium of color.

Personal Struggles, Later Life, and Tragic End

Despite his artistic innovations and the support of figures like Stieglitz, Oscar Bluemner's life was marked by persistent hardship and a lack of widespread recognition. His paintings, while often critically praised, did not sell well. Financial struggles were a constant companion. His German name and perhaps his sometimes-prickly personality may have also presented challenges in the American art market, particularly during and after World War I.

His personal life also saw tragedy. His wife, Lina, passed away in 1926, a devastating loss that deeply affected him. Following her death, he moved to South Braintree, Massachusetts, to live with his son, Robert. During the Great Depression, his financial situation worsened, and he relied for a time on support from the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) and later the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Federal Art Project, government initiatives designed to support artists.

Bluemner continued to paint and write extensively in his diaries, documenting his artistic process and theories. He maintained some connections, like his friendship with Irene Mongepach, whose sonnets inspired a series of crayon, ink, and watercolor sketches known as the "Sonnets Series." One anecdote mentions his fondness for his long-haired orange cat, Florian, a small comfort in difficult times. His relationship with Stieglitz, while foundational, reportedly became strained later in life, possibly exacerbated by Bluemner's decision to privately publish a book on painting in 1929.

In his later years, Bluemner suffered from declining eyesight and deepening depression, fueled by his chronic financial instability, lack of recognition, and personal losses. On January 12, 1938, at the age of 70, Oscar Bluemner took his own life in his South Braintree home. His death marked the tragic end of a unique artistic voice that had struggled for decades against indifference and adversity.

Legacy and Re-evaluation: An Architect of American Modernism

During his lifetime, Oscar Bluemner remained something of an outsider, his work appreciated by a small circle but largely overlooked by the broader public and collecting institutions. However, the decades following his death saw a gradual re-evaluation of his contribution to American art. His unwavering commitment to his personal vision, his innovative synthesis of European modernism with American subjects, and particularly his mastery of color came to be recognized as highly significant.

A crucial factor in his posthumous recognition was the preservation of his artistic estate. His daughter, Vera Bluemner Kouba, carefully maintained his works and extensive painting diaries. In 1997, she made a major donation of over 1,000 works – including paintings, watercolors, drawings, and diaries – to Stetson University in DeLand, Florida. This collection, housed at the university's Homer and Dolly Hand Art Center (previously associated with the Duncan Gallery of Art), became the primary resource for scholars studying Bluemner's life and work, leading to renewed interest and major exhibitions.

Retrospectives and scholarly publications in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, including exhibitions in 2004-2006 that traveled to major museums like the Whitney Museum of American Art (which also holds significant works), firmly established Bluemner's place in the canon of American modernism. He is now seen as a key figure alongside the artists of the Stieglitz circle like Dove, Hartley, Marin, and O'Keeffe, as well as other important modernists who explored the American scene, such as Demuth and Sheeler. His expressive use of color and form is also seen as anticipating aspects of later movements like Abstract Expressionism. His works are now held in major museum collections, including the Whitney, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Art Historical Assessment: Innovation and Isolation

Art historians today generally regard Oscar Bluemner as a highly original and important American modernist painter. His strengths are seen in his innovative fusion of architectural structure with expressive landscape painting, his sophisticated and deeply personal color theory, and his ability to imbue scenes of ordinary American industry and architecture with profound emotional and spiritual resonance. He successfully translated advanced European artistic ideas into a distinctly American context. His extensive diaries provide invaluable insight into his artistic process and the intellectual underpinnings of early American modernism.

However, the assessment also acknowledges the challenges and perceived limitations of his career. His unique style, while innovative, defied easy categorization, perhaps contributing to his marginalization during his lifetime. He fit neatly neither into the established traditions of American landscape painting nor entirely within the dominant narratives of European-derived modernism being forged by Stieglitz and others. His difficult personality and struggles with the art market undoubtedly hampered his success. Some scholars also explore the potential social and political commentary in his work, perhaps reflecting anti-war sentiments or critiques of industrial society during the Depression, themes that were not widely recognized or discussed during his life. His tragic end underscores the often-precarious existence of avant-garde artists working outside the mainstream.

Conclusion: A Singular Voice in Color and Form

Oscar Bluemner's journey from a German architect to a pioneering American modernist painter is a testament to artistic dedication in the face of adversity. He forged a unique visual language, characterized by structural rigor inherited from architecture and an intensely emotional, symbolic use of color inspired by European modernism but applied to the American landscape. Though recognition largely eluded him during his lifetime, his powerful, vibrant canvases and insightful writings ensure his legacy. As a "prophet of color" and an architect of deeply felt modernist compositions, Oscar Bluemner remains a singular and essential voice in the history of American art.