Sigmund Walter Hampel stands as an intriguing figure in the vibrant tapestry of Viennese art at the turn of the 20th century. Active during a period of profound artistic transformation, Hampel navigated the currents of late Romanticism, Symbolism, and the burgeoning modern movements that reshaped the cultural landscape of Europe. While perhaps not as globally renowned as some of his contemporaries like Gustav Klimt or Egon Schiele, Hampel's contributions, particularly his involvement with the Hagenbund and his distinctive thematic and stylistic choices, offer valuable insights into the diverse artistic expressions of his time. His journey from a traditional apprenticeship to a respected member of Vienna's progressive art circles reflects the dynamic interplay between established academic practices and the quest for new artistic languages.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Sigmund Walter Hampel was born in Vienna on July 17, 1867. His early immersion in the world of art was almost preordained, as his father was a glass painter. This familial connection provided Hampel with his initial, formative training. In his father's workshop, he would have learned the practicalities of design, the properties of various materials, and the intricate techniques associated with glass painting. This hands-on experience, focusing on craftsmanship and the decorative potential of art, likely instilled in him a strong technical foundation and an appreciation for meticulous detail and the interplay of light and color, qualities often central to stained glass work.

To further hone his skills and broaden his artistic education, Hampel enrolled in the prestigious Vienna Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien). At the Academy, he immersed himself in the study of the Old Masters, a traditional pedagogical approach that emphasized drawing from classical sculpture, anatomical studies, and copying the works of revered historical painters. This academic training would have exposed him to a wide range of historical styles and techniques, from the Renaissance to the Baroque. It was during this period that Hampel reportedly developed a refined understanding of color application and significantly enhanced his technical capabilities. The discipline of the Academy, combined with his practical workshop experience, equipped him with a versatile skill set.

The Vienna Academy at that time was a bastion of historicism, though it was also beginning to feel the pressures of change. Artists like Hans Makart had dominated the preceding decades with their opulent, large-scale historical and allegorical paintings. While Hampel would have been trained within this tradition, the seeds of modernism were already being sown in Vienna, setting the stage for future artistic departures.

Navigating the Viennese Art Scene: The Hagenbund

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a period of extraordinary cultural ferment in Vienna. The city was a crucible of new ideas in music, philosophy, literature, and the visual arts. A key development was the emergence of artist groups seeking alternatives to the established, conservative Künstlerhaus (the Society of Austrian Artists). The most famous of these was the Vienna Secession, founded in 1897 by artists like Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Josef Hoffmann, and Joseph Maria Olbrich, who broke away to create their own exhibition platform and champion modern art.

Sigmund Walter Hampel became associated with another significant, though sometimes less internationally highlighted, progressive artists' association: the Hagenbund. He was an active member of the Hagenbund from 1900 to 1911. Founded in 1900 (though its roots go back to an informal club of younger artists in the 1870s), the Hagenbund positioned itself as a more moderate alternative to both the conservative Künstlerhaus and the often more radical Secession. It aimed to promote a diversity of contemporary artistic styles, including Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, and early Expressionism, and was particularly noted for its openness to artists from various parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and beyond.

Hampel's membership in the Hagenbund for over a decade indicates his alignment with its progressive yet inclusive ethos. The Hagenbund provided a crucial platform for artists like Hampel to exhibit their work, engage in artistic discourse, and connect with a broader public interested in new art forms. Exhibitions organized by the Hagenbund were known for their innovative installation designs and their diverse range of artworks. Other notable artists associated with the Hagenbund during its influential period included Oskar Laske, Anton Hanak, Carry Hauser, and for a time, even Oskar Kokoschka exhibited with them before his more radical Expressionist path solidified.

Even before his formal involvement with the Hagenbund, Hampel was part of a circle of young artists. Sources indicate his membership in the "Junge Künstler" (Young Artists' Association), which reportedly formed around 1876 and held regular meetings. This group included figures such as Alfred Roller, who would later become a leading stage designer and a key member of the Vienna Secession, Ernst Stöhr, also a founding member of the Secession, the painter Rudolf Bacher, and Hans Tichy. These early associations underscore Hampel's engagement with the forward-thinking artistic currents of his youth, fostering an environment of shared ideas and mutual support.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Influences

Sigmund Walter Hampel's artistic output reflects a blend of influences characteristic of the transitional period in which he worked. His style is often described as being deeply influenced by Romanticism and Symbolism. Romanticism, with its emphasis on emotion, individualism, and the sublime, would have provided a foundation for expressive content. Symbolism, which flourished across Europe in the late 19th century, sought to convey ideas and emotions through suggestive imagery, often drawing on mythology, dreams, and poetic allegory, rather than depicting reality in a literal manner. Artists like Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Fernand Khnopff were key international proponents of Symbolism, and its echoes were strongly felt in Vienna, notably in the early works of Gustav Klimt.

Hampel's thematic concerns often centered on the depiction of female figures and dance forms. The female form was a ubiquitous subject in fin-de-siècle art, often idealized, eroticized, or imbued with symbolic meaning – think of Klimt's femmes fatales or ethereal muses. Dance, too, was a popular theme, capturing movement, grace, and often a sense of escapism or ritual. Isadora Duncan's revolutionary dance performances in Europe, for instance, captivated many artists of the era.

A significant shift or development in Hampel's work is noted after the First World War. During this later period, he reportedly drew inspiration from medieval Italian frescoes. This interest in earlier, pre-Renaissance art forms was not uncommon among artists seeking alternatives to academic classicism or the perceived superficiality of modern life. The simplicity, spiritual depth, and narrative clarity of artists like Giotto or Fra Angelico appealed to many modernists. This influence might have manifested in Hampel's work through a flattening of perspective, a focus on linear design, or a more stylized and symbolic representation of figures and scenes.

His early training in glass painting might also have subtly informed his later work in other media. The emphasis on strong outlines, compartmentalization of color, and the decorative arrangement of forms, inherent in stained glass design, could have translated into his paintings and watercolors, lending them a particular stylistic quality.

Representative Works

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné of Sigmund Walter Hampel's work may not be widely accessible, several pieces are mentioned that provide insight into his artistic preoccupations and style.

Musiksprache in Farben (The Language of Music in Colors): This work, dated to 1938, suggests a Symbolist or synesthetic approach. The title itself implies an attempt to translate the abstract qualities of music into the visual language of color and form. This concept was explored by various artists of the modern era, most famously Wassily Kandinsky, who sought to create a "pure" art analogous to music. Hampel's painting might have employed color harmonies and rhythmic compositions to evoke musical moods or structures, aligning with Symbolist ideals of art appealing to the senses and emotions beyond mere representation. The late date of 1938 places this work in a period of immense political turmoil in Austria, with the Anschluss occurring that year, which adds another layer to its potential interpretation.

Romeo + Juliet: Described as a watercolor, this piece tackles the timeless theme of young, tragic love, drawn from Shakespeare's famous play. Watercolor as a medium allows for fluidity, transparency, and a certain delicacy, which would be well-suited to the romantic and poignant nature of the subject. Without viewing the artwork, one can imagine it capturing a key scene or the emotional essence of the protagonists. The choice of a literary theme is consistent with both Romantic and Symbolist tendencies, where art often drew inspiration from poetry, drama, and legend. This work would likely focus on the emotional intensity and idealized beauty of the young lovers, perhaps rendered with the delicate coloring and refined technique noted in Hampel's training.

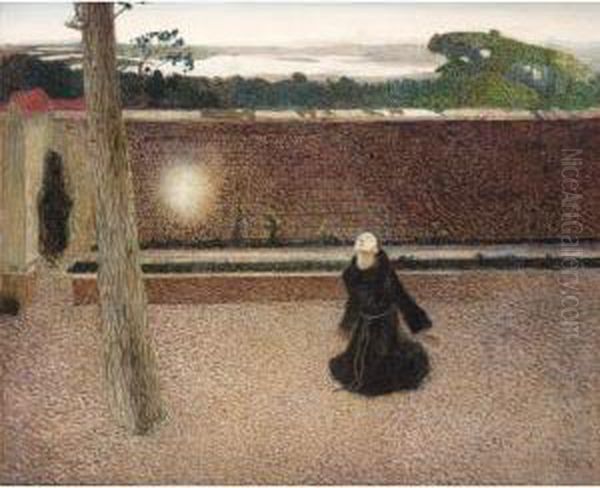

The Vision: This work is particularly notable as it is dated to circa 1949, the year of Hampel's death, suggesting it was among his last creations. The title itself, "The Vision," is evocative and aligns with Symbolist interests in dreams, mystical experiences, and inner worlds. Its exhibition at the Eskenazi Museum of Art (Indiana University Bloomington) indicates its presence in a public collection, allowing for its study and appreciation. Furthermore, its record in an auction on May 28, 2009, held by Beijing Chengxuan Auctions Co., Ltd., points to its circulation in the international art market. As a late work, "The Vision" might offer insights into Hampel's mature style and his enduring thematic concerns at the end of his life.

These works, though only a glimpse into his oeuvre, highlight Hampel's engagement with themes of music, literature, emotion, and the ethereal, all filtered through a style that likely combined academic refinement with Symbolist sensibility.

Contemporaries and the Viennese Milieu

To fully appreciate Sigmund Walter Hampel's position, it is essential to consider him within the constellation of artists active in Vienna during his lifetime. His early association with the "Junge Künstler" group included:

Alfred Roller (1864-1935): A painter and graphic artist who became a pivotal figure in the Vienna Secession and later gained immense fame as a stage designer, particularly for Gustav Mahler's opera productions. Roller's innovative approach to stagecraft revolutionized theatrical design.

Ernst Stöhr (1860-1917): A painter, poet, and musician, Stöhr was a founding member of the Vienna Secession. His work often possessed a melancholic, Symbolist quality, exploring themes of nature, dreams, and introspection.

Rudolf Bacher (1862-1945): A painter and sculptor, Bacher also became a professor at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. He was associated with the Secession and known for his portraits and genre scenes.

Hans Tichy (1861-1925): A painter known for his landscapes, portraits, and genre scenes, often with a lyrical quality. He was also involved with the Secession.

The Hagenbund, to which Hampel belonged for a significant period, fostered a diverse community. While it included artists with more Impressionistic leanings, its overall character was one of moderate modernism. Figures like Oskar Laske (1874-1951), known for his lively, narrative paintings and prints, often depicting bustling city scenes or fantastical events, and the sculptor Anton Hanak (1875-1934), whose work evolved from Art Nouveau towards a more monumental, expressive style, were prominent in the Hagenbund.

Beyond these direct associations, the Viennese art world was dominated by several towering figures whose work defined the era:

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918): The leading figure of the Vienna Secession, Klimt's opulent, decorative, and often erotic paintings, with their use of gold leaf and intricate patterns, became iconic of Viennese Art Nouveau (Jugendstil). His Symbolist allegories and society portraits are world-renowned.

Egon Schiele (1890-1918): A protégé of Klimt, Schiele developed a raw, psychologically intense Expressionist style, particularly known for his contorted self-portraits and nudes. His brief but brilliant career left an indelible mark.

Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980): Another key figure of Austrian Expressionism, Kokoschka's early work was characterized by its psychological insight and bold, agitated brushwork. He, like Schiele, pushed the boundaries of portraiture and figurative art.

Koloman Moser (1868-1918): A highly versatile artist and designer, Moser was a co-founder of the Vienna Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte. He excelled in painting, graphic design, furniture, textiles, and stained glass, embodying the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) ideal.

Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956): An architect and designer, Hoffmann was another co-founder of the Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte. His geometric designs and emphasis on craftsmanship were highly influential in the development of modern design.

Richard Gerstl (1883-1908): An early and radical Austrian Expressionist, Gerstl's intensely personal and stylistically advanced work remained largely unknown during his short lifetime but is now recognized for its pioneering quality.

Max Oppenheimer (MOPP) (1885-1954): A painter and graphic artist associated with Expressionism, Oppenheimer was known for his portraits of contemporary cultural figures and his dynamic depictions of musical performances.

While Hampel's style may have been less radical than that of Schiele or Kokoschka, and perhaps less overtly decorative than Klimt's, his work shared the era's interest in Symbolism and the exploration of inner emotional states. His connection to medieval Italian frescoes also aligns with a broader trend among some modern artists who sought inspiration in "primitive" or pre-academic art forms, a path also explored by artists like Paul Gauguin or the German Expressionists of Die Brücke.

Later Career, Death, and Legacy

Information about Sigmund Walter Hampel's later career, particularly after his involvement with the Hagenbund concluded in 1911 and following the First World War, is less detailed in readily available sources. However, the existence of works like Musiksprache in Farben (1938) and The Vision (c. 1949) confirms his continued artistic activity well into the mid-20th century. His interest in medieval Italian frescoes post-WWI suggests an ongoing evolution in his artistic concerns, perhaps seeking a more timeless or spiritual quality in his art during a period of immense societal upheaval.

The fact that one of his works, The Vision, was created around the time of his death indicates that he remained an active artist until the end of his life. Sigmund Walter Hampel passed away on January 17, 1949, in Nussdorf am Attersee, a municipality in Upper Austria known for its scenic lake, a region that also attracted other artists, including Gustav Klimt who spent many summers there.

Evaluating Hampel's precise influence and legacy is challenging without a more comprehensive overview of his oeuvre and its reception. However, his sustained career, his training at the Vienna Academy, his significant involvement with the Hagenbund, and his exploration of Symbolist and Romantic themes place him firmly within the narrative of Viennese art at a crucial juncture. He was part of a generation that bridged the 19th-century academic traditions and the diverse currents of early modernism.

The inclusion of his work in museum collections like the Eskenazi Museum of Art and its appearance in the art market attest to a continued, if perhaps modest, recognition. Art historians might view Hampel as representative of a particular strand of Viennese modernism – one that was progressive but perhaps less avant-garde than the more radical Expressionists or the leading figures of the Secession. His work likely appealed to a sensibility that valued technical skill, poetic themes, and a refined aesthetic that drew from both historical and contemporary sources.

The mention of a scholarly dispute involving "Hampel" regarding ancient Hungarian decorative styles and their connection to Iranian and Central Asian traditions (challenged by Géza Nagy and Julius Strzygowski) most likely refers to a different Hampel, possibly József Hampel (1849-1913), a prominent Hungarian archaeologist and museum director. It is crucial to distinguish Sigmund Walter Hampel, the Viennese painter, from other individuals with the same surname active in different fields, to avoid misattribution of views or controversies.

Conclusion

Sigmund Walter Hampel emerges as a dedicated artist who contributed to the rich artistic milieu of Vienna from the late 19th century through the first half of the 20th century. His journey began with a solid grounding in craftsmanship through his father's glass painting studio, followed by formal academic training where he honed his technical prowess. His engagement with progressive art circles, most notably his decade-long membership in the Hagenbund, demonstrates his commitment to the evolving artistic landscape of his time.

His art, characterized by influences from Romanticism and Symbolism, and later by an interest in the spiritual depth of medieval Italian frescoes, often explored themes of the feminine, dance, music, and literary romance. Works like Musiksprache in Farben, Romeo + Juliet, and The Vision hint at an artistic vision focused on evoking emotion, conveying symbolic meaning, and capturing a sense of the ethereal or visionary.

While he may not have achieved the same level of international fame as some of his more revolutionary Viennese contemporaries like Klimt, Schiele, or Kokoschka, Sigmund Walter Hampel's career is a testament to the diversity of artistic expression within one of Europe's most vibrant cultural capitals. He represents an important current of artists who, while embracing new ideas, maintained a connection to painterly tradition and a refined aesthetic. His work, and that of the Hagenbund artists, provides a more complete understanding of the complexities and varied paths of Viennese modernism, beyond the most frequently celebrated names. Further research and exhibition of his works would undoubtedly shed more light on his specific contributions and secure his place within the intricate and fascinating history of Austrian art.