Antonio Muñoz Degrain stands as a significant, albeit sometimes idiosyncratic, figure in the landscape of nineteenth and early twentieth-century Spanish art. Born in Valencia on November 18, 1840, and passing away in Málaga on October 12, 1924, his long career spanned a period of profound transformation in European painting. He navigated the currents of late Romanticism, Realism, and the burgeoning influence of Impressionism, forging a distinctive style characterized by vibrant colour, dramatic compositions, and a deep engagement with landscape, history, and literature. While perhaps not achieving the same global household recognition as his slightly younger Valencian compatriot, Joaquín Sorolla, Muñoz Degrain carved out a unique niche, celebrated for his imaginative power and his influential role as an educator.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Valencia

Antonio Muñoz Degrain entered the world in Valencia, the son of a watchmaker. This artisanal background, focused on precision and craft, contrasts intriguingly with the often bold and expressive nature of his later artistic output. His initial artistic inclinations led him to the prestigious Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Carlos in his hometown. There, he received formal training, studying under figures like Rafael Montesinos y Ramiro, a respected painter and educator within the Valencian scene.

Sources also often mention the pivotal influence of Carlos de Haes, the Belgian-born painter who became a naturalized Spaniard and revolutionized landscape painting in Spain through his professorship at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid. While Degrain studied primarily in Valencia initially, the impact of Haes's push towards realism and direct observation of nature, even if interpreted through a romantic lens, permeated Spanish art education during this period. Degrain's early works often reflect this grounding in realistic depiction, particularly in his landscape studies around Valencia.

Despite this formal training, Muñoz Degrain often presented himself, or was perceived by others, as possessing a strong element of self-instruction. This might reflect a certain independence of spirit or a stylistic departure from strict academic norms later in his career. He was known to be an avid reader from a young age, particularly drawn to Romantic literature filled with adventure, exoticism, and dramatic narratives. This literary immersion would profoundly shape his thematic choices and the emotional tenor of his work throughout his life, setting him apart from landscape painters focused solely on topographical accuracy.

Emergence in Málaga and Early Recognition

Muñoz Degrain's professional career began to gain significant traction following his move to Málaga in the 1870s. This city on the southern coast of Spain would become his adopted home for much of his life and a recurring source of inspiration for his landscapes. An early important commission involved decorative work for the Cervantes Theatre in Málaga, showcasing his ability to work on a large scale and integrate artistic elements into architectural spaces.

His connection to Málaga solidified further when, in 1879, he was appointed Professor of Painting at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Telmo in the city. This teaching position marked the beginning of a long and influential pedagogical career. It provided him with financial stability and a platform within the regional art community. During this period, his style began to evolve from a more straightforward realism towards a more eclectic and personal approach, increasingly incorporating the dramatic light and colour that would become his hallmark.

Participation in the Exposiciones Nacionales de Bellas Artes (National Fine Arts Exhibitions) in Madrid was crucial for any Spanish artist seeking recognition and advancement. Muñoz Degrain began submitting works to these prestigious juried shows. Success here could lead to medals, government purchases, and commissions. While initial entries might have met with moderate success, his persistence began to pay off, laying the groundwork for major breakthroughs in the following decade. His contemporaries, like the history painters Eduardo Rosales and Francisco Pradilla Ortiz, were achieving great fame through these exhibitions, setting a high bar for historical and grand narrative painting.

The Italian Sojourn and Historical Masterpieces

A pivotal moment in Muñoz Degrain's career arrived with his success at the National Exhibition of 1881. His painting Otelo y Desdémona (Othello and Desdemona), depicting the tragic Shakespearian couple, garnered significant acclaim, reportedly winning a First Class Medal. This recognition was not merely honorary; it often came with tangible rewards. In Muñoz Degrain's case, this success likely contributed to him securing a grant or opportunity to travel to Italy, a destination considered essential for the formation of any artist working within the European classical tradition.

His time in Italy, likely around 1884, exposed him directly to the masterpieces of the Renaissance and Baroque, the landscapes of the Roman Campagna, and the unique atmosphere of cities like Rome, Venice, and Florence. This experience undoubtedly enriched his artistic vision. It was during or shortly after this period that he produced some of his most famous works, often tackling historical or literary themes with newfound ambition and a heightened sense of drama, possibly influenced by the grand manner paintings he encountered.

One of the most celebrated works associated with this period is Los amantes de Teruel (The Lovers of Teruel). Completed around 1884, this large-scale painting depicts the tragic climax of a famous Spanish medieval legend of doomed love. The painting, now housed in the Prado Museum, is considered a major work of Spanish Romantic painting. It showcases his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions, convey intense emotion, and utilize dramatic lighting and rich colour to enhance the narrative. The work cemented his reputation as a painter capable of tackling grand historical and legendary subjects, placing him in dialogue with established history painters like Alejo Vera or Dióscoro Puebla.

Another significant historical painting was Isabel la Católica entregando sus joyas a Colón (Isabella the Catholic Giving Her Jewels to Columbus). This work, celebrating a key moment in Spanish history linked to the discovery of the Americas, earned him the prestigious Cross of Charles III. Such patriotic themes were popular and officially encouraged, and Muñoz Degrain proved adept at rendering them with suitable gravitas and visual appeal, further enhancing his standing.

Landscape Painting: A Defining Passion

While historical and literary subjects brought Muñoz Degrain significant accolades, landscape painting remained a constant and defining passion throughout his career. His approach, however, diverged significantly from the objective naturalism promoted by Carlos de Haes or the atmospheric subtleties explored by some early Spanish Impressionists like Darío de Regoyos. Degrain's landscapes are often characterized by their subjective intensity, dramatic flair, and a highly personal use of colour.

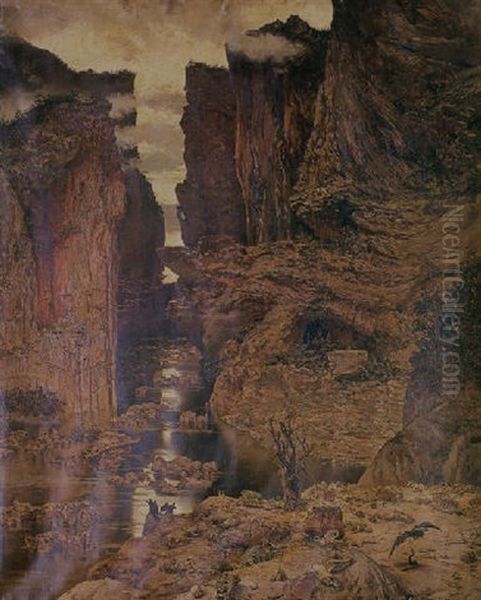

He was particularly drawn to mountainous and rugged terrains, finding inspiration in the landscapes of the Sierra Nevada near Granada, the Pyrenees, and the dramatic gorge of El Chorro near Málaga. His canvases often feature towering peaks, deep valleys, and turbulent skies, rendered with a distinctive palette. He frequently employed vibrant oranges, ochres, violets, and deep greys, using colour not just descriptively but emotionally, to convey the grandeur, solitude, or even menace of the natural world. His application of paint was often bold and energetic, using relatively loose brushwork that prioritized overall effect over minute detail, a trait that led some critics to compare his feeling for light, if not his technique, to that of Mariano Fortuny.

A prime example of his landscape work is Ecos de Roncesvalles (Echoes of Roncesvalles), painted around 1890. This work, likely inspired by the legendary site of Charlemagne's defeat in the Pyrenees, encapsulates his mature landscape style: dramatic composition, evocative use of colour to suggest mood and atmosphere, and a sense of historical resonance embedded within the natural scene. Unlike the Impressionists who sought to capture fleeting moments of light en plein air, Degrain often composed his landscapes in the studio, drawing on sketches but primarily relying on memory and imagination to create highly charged, almost visionary interpretations of nature. His landscapes are less about specific locations and more about the idea or feeling of a place.

Literary Inspirations and Orientalist Visions

Muñoz Degrain's deep love for literature, established in his youth, remained a potent source of inspiration. His engagement went beyond the universally recognized classics like Shakespeare. He drew upon Spanish legends, Romantic poetry, and perhaps even contemporary adventure tales. This literary sensibility infused his work with a narrative quality, even in some landscapes which seem to hint at untold stories or historical dramas unfolding within the scenery. His Lovers of Teruel is the most prominent example, but other works also reference literary or mythological themes, reflecting a Romantic inclination towards storytelling and emotional expression.

His travels extended beyond Italy. Journeys to the Eastern Mediterranean, including Greece and possibly Turkey, exposed him to new landscapes, cultures, and light conditions. This tapped into the prevailing nineteenth-century European fascination with "Orientalism" – the depiction of North African and Middle Eastern subjects. While perhaps not as central to his oeuvre as it was for artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme in France or Antonio Fabrés y Costa in Spain, Muñoz Degrain did produce works reflecting these travels. Sketches and paintings inspired by places like Palermo or depicting scenes with an Eastern flavour added another dimension to his diverse output, showcasing his ability to adapt his style to different subjects while retaining his characteristic emphasis on colour and dramatic effect.

These works, alongside his historical and literary paintings, demonstrate his versatility and his alignment with broader Romantic and post-Romantic trends that valued imagination, emotion, and the exotic alongside the depiction of national history and landscape. He was less concerned with the social realism that preoccupied some contemporaries and more drawn to the realms of legend, history, and the sublime power of nature.

Teaching Career and Academic Leadership

Muñoz Degrain's commitment to art education was a significant aspect of his long career. Following his professorship at the San Telmo Academy in Málaga, his reputation grew, leading to a prestigious appointment at the heart of the Spanish art establishment. In 1895, he succeeded Carlos de Haes as the Professor of Landscape Painting at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid. This was a highly influential position, allowing him to shape the next generation of Spanish landscape painters.

His teaching methods likely reflected his own eclectic approach, perhaps encouraging students to develop personal vision alongside technical skill. While direct accounts of his teaching style are scarce, his own work suggests he valued imagination and bold expression. Later, his stature within the Academy was further recognized when he was appointed its Director, a position of considerable authority and prestige in the Spanish art world. He held this directorship for a period, overseeing the institution's activities and representing it publicly.

During his time in Madrid, he was a prominent figure in the city's vibrant art scene, contemporary to major figures like Joaquín Sorolla, known for his luminous beach scenes, and Ignacio Zuloaga, famous for his darker, more Goya-esque depictions of Spanish life and types. While Degrain's style differed markedly from both, he was part of the same artistic milieu, participating in exhibitions and academic life. Other notable contemporaries whose paths might have crossed with Degrain's in Madrid or at the National Exhibitions include the portraitist Federico de Madrazo (though of an older generation) and landscape painters like Aureliano de Beruete, who embraced Impressionism more fully. His long tenure as a professor means he likely taught or influenced numerous students who went on to have their own careers, although tracing specific stylistic lineages can be complex.

Style and Technique: A Unique Vision

Antonio Muñoz Degrain's style is notoriously difficult to categorize neatly. It borrows elements from various movements without fully adhering to any single one. His early work shows roots in Realism, particularly in landscape, likely influenced by the Haes school. However, his temperament leaned towards the dramatic and subjective, aligning him with Romanticism's emphasis on emotion and imagination. This is evident in his choice of historical and literary themes and the often-theatrical staging of his compositions.

His handling of colour is perhaps his most distinctive feature. He employed a bright, often non-naturalistic palette, using bold contrasts and unexpected juxtapositions to create visual excitement and emotional impact. His use of intense oranges, violets, and blues, particularly in rendering skies and mountains, became a signature. This vibrant chromaticism, combined with a relatively loose and energetic brushstroke, particularly in his later works, has led some to see proto-Impressionist tendencies. However, unlike French Impressionists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, Degrain was less concerned with the scientific observation of light effects and more interested in using colour expressively. His light is often dramatic and artificial-seeming, highlighting specific elements for narrative or emotional emphasis rather than capturing a fleeting natural moment.

Compared to the sun-drenched, optimistic luminosity of Sorolla, Degrain's light can feel more theatrical, even mystical. Compared to the detailed finish of academic history painters like Francisco Pradilla Ortiz, Degrain's surfaces can seem rougher, prioritizing overall impact. This sometimes led to criticism regarding a perceived lack of finish or anatomical precision in his figures. Yet, it is precisely this boldness, this willingness to sacrifice detail for expressive power and chromatic intensity, that constitutes his unique contribution. He forged a personal style that blended romantic sensibility with a modern, almost Fauvist, approach to colour, years before the Fauves emerged in France. Other Valencian painters like Ignacio Pinazo Camarlench also explored looser brushwork and light effects, contributing to the region's rich artistic output.

Later Years and Legacy

Muñoz Degrain remained active as a painter and influential figure well into the twentieth century. He continued to exhibit his work both nationally and internationally, receiving recognition at events like the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893) and art exhibitions in Munich. His distinctive style, while perhaps falling out of step with the avant-garde movements emerging after 1900, remained popular with certain collectors and institutions.

He spent his final years primarily in Málaga, the city that had become his true home. In a gesture of generosity and civic pride, he donated a significant number of his works to Spanish museums, particularly the Museo de Bellas Artes (now Museo de Málaga) in Málaga and the Museo de Arte Moderno (whose collections are now largely integrated into the Prado Museum and the Reina Sofía Museum) in Madrid. This act ensured that his legacy would be preserved and accessible to future generations. His death in Málaga in 1924 marked the end of a long and remarkably productive career.

Today, Antonio Muñoz Degrain is recognized as a major figure in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Spanish art. While his eclectic style defies easy classification, his importance lies in his unique synthesis of Romantic imagination, realistic observation (particularly in landscape), and a bold, expressive use of colour that anticipated later modernist developments. He excelled in multiple genres – landscape, history, literature, Orientalism – and left behind a substantial body of work characterized by its energy, vibrancy, and dramatic power. His long career as an influential educator further solidifies his place in the annals of Spanish art history, representing a fascinating bridge between nineteenth-century traditions and the emerging sensibilities of the modern era. His works continue to be studied and appreciated for their distinctive vision and their contribution to the rich tapestry of Spanish painting, holding their own alongside those of contemporaries like Emilio Sala Francés or José Benlliure y Gil.

Conclusion

Antonio Muñoz Degrain navigated the complex artistic landscape of his time with a singular vision. From his academic beginnings in Valencia to his influential teaching posts in Málaga and Madrid, and through his extensive travels and prolific output, he remained dedicated to an art of heightened emotion and vibrant colour. Whether depicting the rugged mountains of Spain, the tragic lovers of Teruel, or scenes inspired by Shakespeare or Eastern travels, his work consistently displays a dramatic intensity and a unique chromatic sensibility. Though sometimes overshadowed by contemporaries who more fully embraced Impressionism or maintained stricter academic standards, Muñoz Degrain's fusion of Romantic narrative, landscape passion, and near-expressionistic colour marks him as a significant and original voice in Spanish art. His legacy endures through his captivating paintings and his contribution to the education of subsequent generations of artists.